Introduction

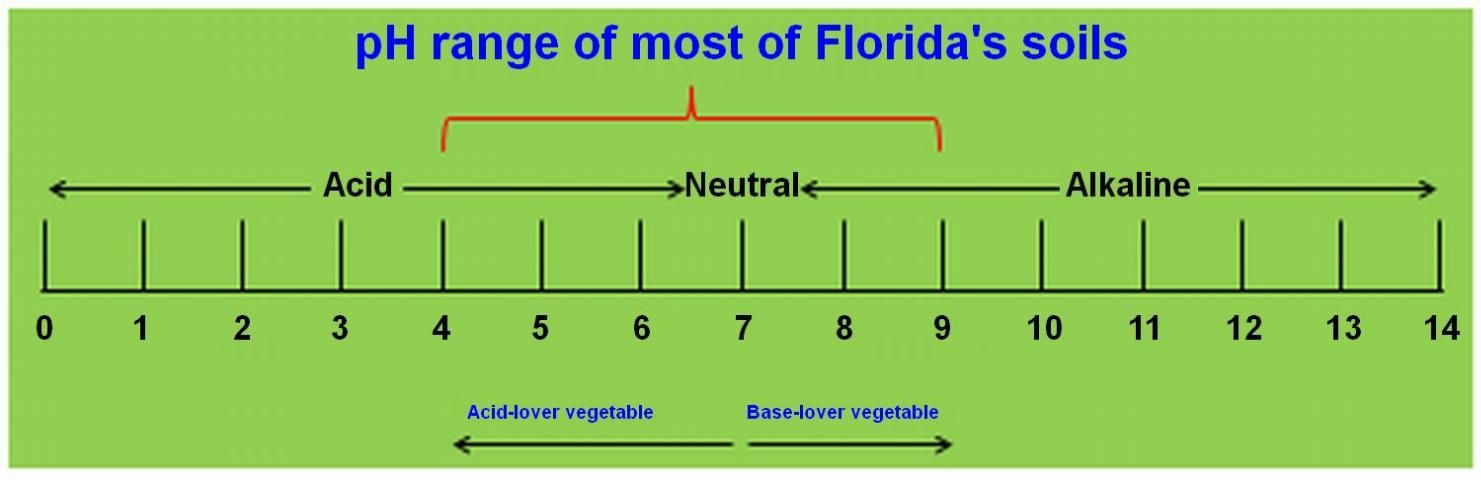

Soil pH is a measure of soil acidity or basicity, and it is defined as the negative logarithm of the proton (H+) activity. The pH ranges from 0 to 14. A pH of 7.0 is defined as neutral, while a pH of less than 7.0 is described as acidic, and a pH of greater than 7.0 is described as basic or alkaline (Figure 1). According to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (1993), soil pH ranges roughly from acidic (pH < 3.5) to very strongly alkaline (pH > 9.0). Soil pH is a master characteristic in soil chemical properties because pH governs many chemical processes. The pH specifically affects nutrient bioavailability by controlling the chemical forms of nutrients. For example, ferrous iron is a bioavailable form of iron for most crop species, but ferric iron is not. At a relatively high pH, ferric iron is the primary form, and crop plants may experience iron deficiency.

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

As one of the most important soil chemical properties for optimal crop production, soil pH determines nutrient sufficiency, deficiency, toxicity, and potential need for liming (Fageria and Zimmermann 1998) or addition of sulfur. The pH range of most of the Florida's soils is approximately between 4.0 and 9.0 (Figure 1; Tables 1–4). Because nutrient solubility is highly pH dependent, soil pH near 4.0 or 9.0 is usually not suitable for commercial vegetable production. A pH-range from 5.5 to 7.0 is suitable for most vegetable crops. From a solubility point of view this pH range can assure high bioavailability of most nutrients essential for vegetable growth and development (Ronen 2007). For example, at soil pH 8.0 or higher, iron and/or manganese bioavailability cannot satisfy most vegetable crops' nutrient requirements. However, when soil pH reaches 5.0 or lower, aluminum (Al), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and/or zinc (Zn) solubility in soil solution becomes toxic to most vegetable crops (Osakia, Watanabe, and Tadano 1997).

This publication is intended to provide information about soil pH basics to commercial vegetable growers, certified crop advisers (CCAs), crop consultants, UF/IFAS Extension agents, and college students specializing in vegetable production.

Effects of Soil pH on Vegetable Crop Growth and Development

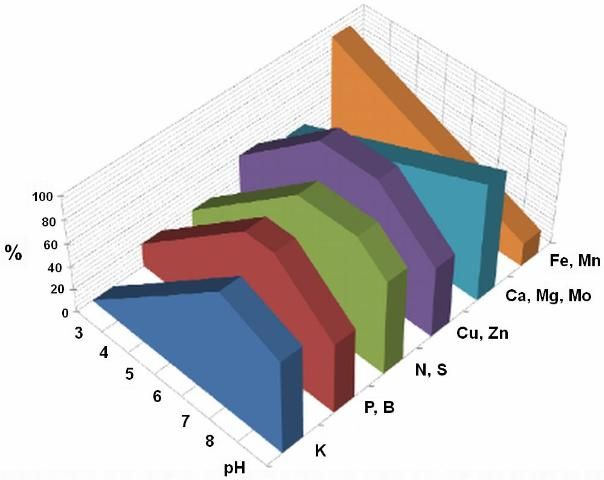

Effects on cation and anion nutrients: Soil pH determines the solubility and bioavailability of nutrients essential for crop production. There are seventeen (17) elements essential for the normal life cycle of vegetable crops. Based on the source, the seventeen nutrient elements can be roughly categorized into two groups: three “free” nutrients from air and water, which are carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O), and fourteen soil nutrients, which are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sulfur (S), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), boron (B), chlorine (Cl), molybdenum (Mo), and nickel (Ni). The bioavailable forms of all the soil nutrients are ionic—some are anionic (negatively charged, such as phosphorus), some cationic (positively charged, such as potassium), and some are both (such as nitrogen: nitrate ions or ammonium ions). For example, P, S, Cl, and Mo are typical anion nutrients, and K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn, and Ni are typical cation nutrients, but N can be either anions or cations. Boron is predominately undissociated boric acid (H3BO3 or B(OH)3), but less than 2% of B is in the form of an anion B(OH)4- at pH 7.5 or lower. The solubility (i.e., bioavailability) of each of these fourteen nutrient elements is closely related to soil pH. At pH lower than 5.0, Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn are highly soluble. These micronutrients can form precipitates with phosphate at this low pH, and P becomes unavailable accordingly. However, at pH greater than 7.0, Ca and Mg have high solubility, and they can immobilize P as well. Thus, comprehensively speaking, in the pH range from 5.5 to 7.0, all the nutrients have favorable solubility for use by vegetable plants (Figure 2).

Credit: Finck (1976)

Effects on nutrient uptake near the root zone: Soil pH also affects nutrient uptake by vegetable plants because pH can change soil particle properties. For example, if soil pH is unfavorably low, the positive charges on soil particle surfaces can tightly retain nutrients such as P, potentially causing P deficiency. However, if soil pH is adversely high, then Fe, Mn, and Zn will become difficult for vegetable plants to use. In one study, bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) absorbed 93.3% more P, 53.8%, more Fe, and 44.1% more Zn at pH 5.4 than at pH 7.3, respectively (Thomson, Marschner, and Römheld 1993). The lower pH favors P, Fe, and Zn uptake because the bioavailability of P, Fe, and Zn is greater at pH 5.4 than at pH 7.3 (Figure 3).

Effects on metal toxicity: Basically, metal toxicity occurs at soil pH lower than 5.0 when elements such as Al, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn have much greater solubility than crop nutrient requirements (CNRs). To avoid this problem, lime is needed to increase soil pH and decrease the potential for toxicity.

Effects on plant pathogens: Some soilborne diseases are closely associated with soil pH. For example, clubroot disease of mustard, cabbage, or other crucifers caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae is a major epidemic disease when soil pH is lower than 5.7 and is dramatically reduced in a pH range from 5.7 to 6.2. This disease is virtually eliminated when the soil pH is greater than 7.3. Similarly, common scab of potato is favored when the pH is greater than 5.2 but significantly reduced at less than 5.2 (Kioke et al. 2003). Within the soil pH range from 5.2 through 8.0, the severity of the common scab increases with soil alkalinity (Nisa et al. 2022).

Statewide Overview of Soil pH

Florida is a unique state in terms of soil diversity. Its soil pH significantly differs in the entire state from north to south and east to west. Even in the same county, soil pH can differ by as much as 6 pH units, according to the USDA soil survey (USDA 1976, 1979, 1983, 1996). For example, soil pH ranges from 3.6 to 9.0, from 3.6 to 9.0, from 3.3 to 9.0, and from 3.6 to 8.4 for Dade County, Palm Beach County, St. Johns County, and Jackson County, respectively (Tables 1 through 4). These extremes are all unfavorable for vegetable production.

Nutrients and Soil pH

Nutrient bioavailability: Nutrient bioavailability is usually a limiting factor in commercial crop production because of solubility limitation or immobilization of plant nutrients by soil colloids. A nutrient's bioavailability is the proportion of that nutrient that is soluble or mobilized by root exudates, including protons (directly related to soil pH), chelates, mucilage and mucigel, or microbial products (Neumann and Römheld 2012). For instance, in the Everglades Agricultural Area, total P in cultivated soil is up to 1,227 parts per million (ppm), but bioavailable P is only 1.3 ppm (Wright, Hanlon, and McCray 2009). The bioavailability of that soil is only 0.1% of the total P. Thus, P deficiency does not mean lack of P in that soil, but it does mean lack of absorbable or usable P for crop plants.

Nutrients needed in large amounts by vegetable plants are called macronutrients, such as N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and S, whereas those needed in trace amounts are referred to as micronutrients or trace nutrients, such as Fe, Mn, B, Zn, Cu, Cl, Mo, and Ni. Soil pH affects both macronutrient and micronutrient solubility (Figure 2) and bioavailability. For example, the primary form of iron in dry soil is ferric hydroxide (Fe(OH)3) because ferrous iron is easily oxidized and little ferrous iron exists in dry soil, particularly at soil pH 7.3 or higher. The solubility of ferric hydroxide is only 6.3 × 10-20 mol/L (i.e., only 3.0 × 10-17 lbs Fe per 1000 gallons of water at pH 7.3). However, its solubility is 1.34 × 10-5 mg Fe per 1000 gallons of water at pH 5.3. The solubility increases one million times when soil pH is lowered just two pH units. This dramatic change in solubility can explain why iron deficiency symptoms often occur when soil pH is 7.3 or higher. If the soil is appropriately wet and soil pH is neutral or slightly acidic, a considerable proportion of iron exists in the form of ferrous iron, usually enough to satisfy crop nutrient requirements for Fe.

Soil pH influence on uptake of cation and anion nutrients: In low-pH soils, the hydrogen ion exists as a hydrated proton and may become a toxicant if soil pH is lower than 3.0 (Liu et al. 2007). However, the effects of soil pH on nutrient intake are mainly indirect, caused by increasing the solubility of toxic metals, such as Al. Aluminum solubility is also a function of soil pH. The solubility of Al increases as soil pH decreases. At pH 5.5 or lower, the solubility of Al increases 1000-fold for every pH unit decrease. For example, at pH 5.0, Al solubility is only 0.05 ppm, but at pH 4.0, Al solubility increases to a toxic level of 51 ppm.

These high concentrations of Al can damage root morphology and induce P deficiency in soil (Figure 3). The root system of corn can be seriously damaged, or its growth retarded when Al concentration is greater than 9 ppm (Lidon and Barreiro 1998). Aluminum and phosphate precipitate in low-pH soil. Both Al and P have a reciprocal relationship. As mentioned above, Al solubility is 1000-fold greater at pH 4.0 than at pH 5.0. Because of the Al concentration increase, the bioavailability of P at pH 4.0 reduces to one thousandth of the concentration present at pH 5.0, having been precipitated by the increase in Al. Similar effects for other elements can be seen in Figure 3. In the Hastings area, the soil contains roughly 2,000 pounds of Mehlich-3 extractable aluminum and up to 1,200 pounds of Mehlich-3 extractable phosphorus. In the potato growing season, soil pH drops by one pH unit from pH 6 to pH 5. In this case, most of pre-plant application of phosphate fertilizer becomes unavailable to potato plants.

Low pH exacerbates nutrient leaching problems because cation nutrients adsorbed by soil particles may be replaced by protons in soil solution. Nutrient leaching out of the root zone also reduces nutrient uptake and nutrient use efficiency of vegetable crops.

Effects on nutrient uptake near the root zone: In the presence of toxic concentrations of elements such as Al at low pH, root growth and water uptake are inhibited, and plants may show symptoms of P deficiency and drought stress. Aluminum-stressed plants cannot efficiently absorb nutrients from the soil solution. There are two other reasons for inhibition of cation nutrient uptake and induction of nutrient deficiency: (a) impairment of net excretion of protons and (b) decrease of bioavailable cation nutrients, such as Ca, Mg, Zn, and Mn in soil solution.

Effects of Soil pH on Microbial Activity

The pH affects microbial activity, which in turn can affect the bioavailability of both macronutrients and micronutrients. Most soil microbes thrive in a range of slightly acidic pH (6–7) due to the high bioavailability of most nutrients in that pH range (Sylvia et al. 2005). Because microbes can increase nutrient bioavailability and promote plant nutrient uptake, vegetable crops can also thrive in similar environments (Das et al. 2010).

Nutrient Sources Affect Soil pH in Root Zones

Acid-forming or base-forming fertilizers: Acid-forming fertilizers are defined as those that lower rhizosphere pH after being absorbed by plants. All fertilizers containing cation nutrients, such as ammoniacal-N, K, Ca, and Mg, are acid forming, whereas those having anion nutrients, such as nitrate N, P, and S, are basic forming. For instance, ammonium chloride, potassium chloride, calcium chloride, and magnesium chloride are all acid-forming fertilizers. However, sodium nitrate, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, and sodium sulfate are all basic-forming fertilizers.

Acid- or base-forming fertilizer is NOT related to the acidity or basicity of the applied fertilizer itself. The acidity or basicity results from the selective uptake of nutrients by crop plants. For example, potassium chloride (KCl) is chemically neutral. Potassium and chlorine (Cl) are both essential for vegetable crop growth and development. However, the ratio of plants' K requirement to Cl requirement is greater than 80. This ratio shows that plants need to absorb more than 80 K+ ions when they take up one Cl- ion from KCl. These two nutrients are either positively or negatively charged. When plants take up these two kinds of cation and anion ions selectively without electrical neutralization, plant cells would accumulate tremendous positive charges. These unbalanced charges can kill the cells immediately. To avoid this, plant cells have developed two strategies. In the first strategy, they stoichiometrically release the same type of charges, such as protons (H+), when they absorb K+. In the second strategy, the cells can also neutralize the unbalanced charges by absorbing the same number of other ions with counter charges, such as OH- or HCO3-, in this case when they take up K+ ions. Regardless of strategy, the net consequence is the same: The pH in the growth medium, particularly in the root zone, is decreased. Similarly, sodium nitrate (NaNO3) is chemically neutral, but the pH in the root zone is increased when the plant takes up NO3- from NaNO3 because nitrate N is negatively charged and the primary nutrient in crop production, but sodium is not essential for crop growth and development. Therefore, intentional selection of fertilizers, such as KCl or NaNO3, can effectively adjust soil pH in the root zone to some extent, if needed. However, at fertilizer rates to satisfy the crop nutrient requirements, the pH change may be small. Most pH changes for vegetables are more effective and often lower cost when using agricultural lime to raise soil pH or S (in several forms) for lowering soil pH.

Soil pH vs. Nutrient Losses

Ammonia volatilization: Ammonium-N is one of the two primary forms of commercial N fertilizers. Ammonium (NH4+) and ammonia (NH3) can form a dynamic chemical equilibrium in soil solution. The shifting of the chemical equilibrium between NH4+ and NH3 is determined by the pH of soil solution. At pH 9.2, both NH4+ and ammonia are equal in concentrations. Ammonium is aqueous, but ammonia is both aqueous and gaseous in solution. The solubility of ammonia in water is 31% at 77°F (25°C). This dissolved NH3 can easily be converted into gaseous NH3 that is ultimately released into the atmosphere. This gas emission process is called NH3 volatilization. Soil pH mainly determines the extent of the NH3 volatilization. High soil pH (greater than 7.2) causes NH3 volatilization from fertilized soils with ammoniacal-N sources, such as ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4), or ammonium-forming fertilizers, such as urea. In Florida, NH3 volatilization was up to 26% of the applied N fertilizer in Krome Very Gravelly Loam soil in Homestead for vegetable production (Liu et al. 2007).

Anionic nutrient leaching: At soil pH greater than 7.0, hydroxide ions can replace anionic nutrients from soil particles with positive charges and reduce soil particles' anionic nutrient-holding ability. Nitrate leaching increases proportionately as soil pH increases (Costa and Seidel 2010). Therefore, high soil pH exacerbates anionic nutrient leaching and reduces nutrient use efficiency. To alleviate leaching problems and improve the profitability of vegetable production, soil pH needs to be effectively managed by liming acidic soil or sulphuring alkaline soil or other means as needed.

Micronutrients: In addition to soil pH, micronutrients are affected by ionic charge (some can have more than one, like Mn and Fe, which is often determined by microsite conditions and oxidation-reduction potential). For example, in appropriately wet soil (between field capacity and wilting point), Fe and Mn are more bioavailable than in dry soil because wet soil has lower oxidation-reduction potential than dry soil. In the same soil, the oxidation-reduction potential increases with pH. This process explains Fe or Mn deficiency in high pH soils, namely as a function of pH greater than 7.0 and during drier soil moisture conditions, which favor deficiency.

Nutrient Use Efficiency

Nutrient use efficiency is defined as vegetable yield per unit of nutrient input. Seeking efficiency is much more important than ever before because fertilizer prices have risen, and profit margins have become thin. Nutrient use efficiency can be measured by calculating the productivity of each component of a nutrient. In 2012, two snap bean trials were done in Lake Harbor and Belle Glade in Palm Beach County. The two trials both showed that 120 lb. phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5) per acre was the most efficient P rate. The P use efficiency in snap bean production varied with the trial locations. In Lake Harbor, 1 lb. of P fertilizer yielded 11 lb. of beans. The P use efficiency for this trial in Lake Harbor was 11 (lb./lb.). However, in Belle Glade, 1 lb. of P yielded 22 lb. of beans. The P use efficiency in Belle Glade was 22 (lb./lb.). This difference in P use efficiency can be attributed to the bioavailability of P in soil properties (Liu et al. 2015).

Modifying Soil pH or Choosing Plants That Will Thrive in Soil

Adjusting soil pH usually involves raising the soil pH by adding agricultural lime if soil pH is too low.

Acidic soils: The bioavailability of Ca, Mg, or Mo is often low and may adversely affect vegetable production. Additionally, toxicity effects discussed previously may also be a factor. An increased soil pH can improve nutrient availability and help avoid toxicity.

Lime and lime requirement: The most common soil additive to increase soil pH is agricultural lime, usually finely ground. The amount of lime required to increase soil pH is determined by the size of the limestone particles being used and, most importantly, the buffering capacity of the soil. The buffering capacity refers to the soil's capacity to minimize change in the acidity of a solution when an acid or base is added into the solution. The finer the ground lime, the quicker the neutralization reaction and soil pH changes. Buffering capacity is controlled by the soil's clay content and the amount of organic matter present. Soils with more clay content have a greater buffering capacity than soils with less clay content. Similarly, soils with more organic matter have higher buffering capacity than those with lower organic matter. Soils with large buffering capacity need more agricultural lime to adjust soil pH than those with lower buffering capacity for the same incremental change in soil pH. However, sandy soils have lower buffering capacity and need less lime for the same incremental change in pH than clay soils.

The best way to determine the lime requirement for a soil is to take a soil sample to the UF/IFAS Extension Soil Testing Laboratory. UF/IFAS Extension faculty members can also help. For more information, see Soil pH and the Home Landscape or Garden (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS480), Managing pH in the Everglades Agricultural Soils (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS500), The Vegetarian Newsletter, Issue 573 (http://hos.ufl.edu/newsletters/vegetarian/issue-no-573), and The Soil Test Handbook for Georgia (https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/soil/STHandbook.pdf).

Other amendments, such as dolomite (a white or light-colored mineral, essentially CaMg(CO3)2), wood ash, industrial burnt lime (calcium oxide), and oyster shells can also increase soil pH. These sources increase soil pH through the reaction of carbonate and protons to produce carbon dioxide and water. However, some wood ash may contain sodium or heavy metals. Before using any of these sources, consult your county Extension agent. Applying calcium silicate can also neutralize active acidity in soil. Local organic sources, such as yard-trash compost and sphagnum moss peat, are all acidic. The pH range can be as low as 3.6–4.2. These sources can be used to neutralize free hydroxide and/or bicarbonate ions.

Use nitrate nitrogen fertilizers: Liming can change the whole surface-soil layer's pH. If nitrate nitrogen fertilizers are used, the root zone's pH can be increased without additional cost because vegetable crops need to balance electrically after absorbing nitrate ions, which are negatively charged. Since N should be added according to recommended fertilizer rates, this process works slowly for the entire soil profile, but it does improve the plant root zone pH in a short period of time.

Alkaline soils: The bioavailability of P, Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, or Ni is low and may adversely affect vegetable growth and development. To ensure that vegetable crops will grow well, soil pH may need to be reduced if the high pH was caused by overliming or poor irrigation water quality. If the high pH was caused by a natural condition, usually limestone or beach shells in Florida, the change is too costly. Selection of appropriate cultivars is a must in such a case.

Sulfur and sulfur requirement: The most common soil additives to decrease soil pH are elemental sulfur (S), iron sulfate or aluminum sulfate, ((NH4)2SO4), peat moss, or any cation nutrients, such as NH4+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. Therefore, these fertilizers can all decrease soil pH: urea, urea phosphate, ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), ammonium phosphates such as monoammonium phosphate, i.e., MAP, (NH4H2PO4) and diammonium phosphate, i.e., DAP, ((NH4)2HPO4), (NH4)2SO4, and monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4). Organic matter in the form of plant litter, compost, and manure all decrease soil pH through the decomposition process. Certain acidic organic matter, such as pine needles, is also effective at reducing pH.

Applying elemental sulfur can decrease soil pH because the applied sulfur can form sulfuric acid and neutralize free hydroxide or bicarbonate ions in the soil. Like the lime requirement for low-pH soils, sulfur requirement for high-pH soil is closely related to the buffering capacity of the target soil. The UF/IFAS Extension soil testing lab offers a Lime Requirement test as a component of a routine soil test, which provides a liming recommendation based on the buffer capacity of the soil sample. Additionally, Kissel and Sonon (2008) provide an informative reference to determine the actual amount needed for a high-pH soil. If the high pH is naturally occurring, then lowering soil pH with sulfur is not recommended. It is better to discuss lowering soil pH with a local county Extension agent before taking any action.

Use ammonium nitrogen fertilizers: Ammoniacal-N fertilizers, such as (NH4)2SO4 and NH4Cl, and ammonium-forming fertilizers, such as urea, can significantly decrease root zone pH after plants take up NH4+ ions from soil. Using suitable fertilizers to adjust soil pH doesn't necessarily incur any additional cost and may improve the profitability of vegetable production. Applying organic matter, such as compost, manure, and pine sawdust, is also effective at reducing soil pH. If soil pH is too low, refer to Diagnostic Nutrient Testing for Commercial Citrus in Florida (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS492).

Optimal Soil pH

To enhance vegetable production productivity, optimal soil pH range is essential. Tables 1 through 4 indicate the soil pH ranges in selected counties. The pH ranges for other counties can be found at http://soils.usda.gov/survey/online_surveys/florida/. Figure 1 contains the pH scale and vegetable category based on their tolerance to acidity levels. Figure 2 indicates the relationship between nutrient bioavailability and soil pH.

References

Costa, A. C. S. d., and E. P. Seidel. 2010. "Nitrate Leaching from a Latosol after Application of Liquid Swine Manures in Different pH Values and Organic Matter Contents." Acta Sci., Agron 32(4): 743–748.

Das, A., R. Prasad, A. Srivastava, P. H. Giang, K. Bhatnagar, and A. Varma. 2010. "Fungal Siderophores: Structure, Functions and Regulation." In Microbial Soderophores (Soil Biology), edited by A. Varma and S. B. Chincholkar, 1–42. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Fageria, N. K., and F. J. P. Zimmermann. 1998. "Influence of pH on Growth and Nutrient Uptake by Crop Species in an Oxisol." Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 29 (17&18): 2675–2682. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103629809370142. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

Finck, A. 1976. Pflanzenernährung in Stichworten. Kiel, Germany: Verlag Ferdinand Hurt.

Havlin, J. L., J. D. Beaton, S. L. Tisdale, and W. L. Nelson. 2005. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: An Introduction to Nutrient Management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Kioke, S., K. V. Subbarao, R. M. David, and T. A. Turini. 2003. Vegetable Diseases Caused by Soilborne Pathogens. Publication 8099. Davis: University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8099.pdf. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

Kissel, D. E., and L. Sonon, eds. 2008. Soil Test Handbook for Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia. https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/soil/STHandbook.pdf. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

Lidon, F. C., and M. G. Barreiro. 1998. "Threshold Aluminum Toxicity in Maize." Journal of Plant Nutrition 21(3): 413–419.

Liu, G.D., K. Morgan, B. Hogue, Y.C. Li, D. Sui. 2015. Improving Phosphorus Use efficiency for Snap Bean Production by optimizing Application Rate. Horticultural Science 42: 94-101. https://doi.org/10.17221/229/2014-HORTSCI. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

Liu, G. D., J. Dunlop, T. Phung, and Y. C. Li. 2007. "Physiological Responses of Wheat Phosphorus-Efficient and -Inefficient Genotypes in Field and Effects of Mixing Other Nutrients on Mobilization of Insoluble Phosphates in Hydroponics." Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 38(15–16): 2239–2256. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103620701549249. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

Neumann, G., and V. Romheld. 2012. "Rhizosphere Chemistry in Relation to Plant Nutrition." In Marschnar's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (3rd ed.), edited by P. Marschnar, 347–368. New York: Elservier.

Osakia, M., T. Watanabe, and T. Tadano. 1997. "Beneficial Effect of Aluminum on Growth of Plants Adapted to Low pH Soils." Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 43(3): 551–563.

Relley, H. E., and C. L. Shry, Jr. 1997. Introductory Horticulture (5th ed.). Albany, NY: Demar Publishers.

Ronen, E. 2007. "Micro-Elements in Agriculture." Practical Hydroponics & Greenhouses July/August: 39–48.

Sylvia, D. M., J. F. Fuhrmann, P. G. Hartel, and D. A. Zuberer. 2005. Principles and Applications of Soil Microbiology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Splittstoesser, W. E. 1990. Vegetable Growing Handbook: Organic and Traditional Methods (3rd ed.). New York: Chapman & Hall.

Thomson, C. J., H. Marschner, and V. Römheld. 1993. "Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizer Form on pH of the Bulk Soil and Rhizosphere, and on the Growth, Phosphorus, and Micronutrient Uptake of Bean." Journal of Plant Nutrition 16 (3): 493–506.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 1976. "Soil Survey of Palm Beach County Area, Florida." Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://nrcs.app.box.com/s/d0hq4ddo8t8otkwaejj131xp7xo0yi9g/file/982463168283. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 1979. "Soil Survey of Jackson County Area, Florida." Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://nrcs.app.box.com/s/d0hq4ddo8t8otkwaejj131xp7xo0yi9g/file/982404626115. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 1983. "Soil Survey of St. Johns County Area, Florida." Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://nrcs.app.box.com/s/d0hq4ddo8t8otkwaejj131xp7xo0yi9g/file/982433448104. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 1993. "Soil Survey Manual: Chapter 3." Natural Resources Conservation Service. http://soils.usda.gov/technical/manual/contents/chapter3.html. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 1996. "Soil Survey of Dade County Area, Florida." Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://nrcs.app.box.com/s/d0hq4ddo8t8otkwaejj131xp7xo0yi9g/file/982460499981. Accessed on February 5, 2024.

Wright, A. L., E. A. Hanlon, J. M. McCray. 2009. Fate of Phosphorus in Everglades Agricultural Soils after Fertilizer Application. SL290. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS503. Accessed on February 5, 2024.