Introduction

This publication is intended for the public with little to no knowledge of entomology and invertebrate biology. It aims to help readers identify the most common beneficial insects and invertebrates found in Florida gardens and promote their populations to minimize the use of insecticides. Entomologists or professionals who want to have a more detailed description of the different natural enemies can find them in the Featured Creatures series from the UF/IFAS Department of Entomology and Nematology: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/collections/series_featured_creatures.

Good Bugs and Bad Bugs

Any organism that feeds on or competes with another organism and decreases its survival is its natural enemy. Insects that are natural enemies of pest insects are beneficial insects. Other invertebrates, such as spiders and predatory mites, and some nematodes that parasitize insects are also beneficial.

There are two main types of beneficial invertebrates, predators and parasitoids. Predators, such as ladybird beetles and spiders, attack different kinds of insects and consume several prey throughout their life cycle. Parasitoids are wasps or flies that lay their eggs on or inside other arthropods; they are also called parasites. The egg hatches and the immature parasitoid feeds on the victim, called a host, eventually killing it. Each developing parasitoid kills only one host during its life cycle. Parasitoids are usually more specific in the insects they attack than predators. When a host is parasitized by more than one parasitoid, this is referred to as superparasitism.

Controlling Pests Biologically

Biological control is an approach to reducing populations of harmful organisms with natural enemies. Organisms introduced from other parts of the world are called exotic or nonindigenous, as opposed to native or indigenous. Pests may be introduced into the United States and become established without natural enemies to keep them in check. Biological control of nonindigenous organisms involves finding a pest's native complement of natural enemies and introducing them into the new area where the pest has become established. Recent examples of successful introduction of natural enemies include the Asian citrus psyllid's parasitoid Tamarixia radiata, or the chrysomelid beetle Lilioceris cheni that feeds exclusively on the invasive air potato vine. All nonindigenous natural enemies must be carefully studied prior to release to determine that they target only a specific pest and will not have an adverse environmental or economic impact.

The effectiveness of both introduced and native natural enemies can be enhanced through mass-rearing for release (augmentation) or by modifying the environment to favor them (conservation). Many beneficial arthropods can be purchased from commercial insectaries for augmentative release. Ladybird beetles, predatory mites, and lacewings are examples of predators that can be ordered and shipped through the mail to help control aphids, whiteflies, and other pests. Parasitoids of whiteflies, caterpillar eggs, and other pests may be purchased for release into a farm, garden, or greenhouse.

Purchasing Natural Enemies for Release

Producers of greenhouse-grown foliage, flowers, and vegetable crops sometimes augment natural biological control through the purchase of predators and parasitoids. Occasionally, this is also done for field-grown crops in Florida, such as in strawberry production. Home gardeners frequently ask about supplementing the natural biological control in their gardens and yards.

There are many commercial sources of natural enemies. However, quality varies among producers, so the purchaser should consider suppliers that have been in business for at least several years. It is also important to determine if the company produces the beneficial arthropods or only distributes them. The consumer should buy directly from the producer of the biocontrol agents if possible and receive instructions on how they should be used.

Selecting a natural enemy for purchase requires that the habits and habitats of the natural enemy match the characteristics of the pest. For example, Trichogramma egg parasitoids are often useful for moths, the predatory mite Phytoseiulus for spider mites; the predatory mite Neoseiulus (Amblyseius) for thrips and mites; Cryptolaemus lady beetles for mealybugs and scales; spined soldier bugs for caterpillars; and lacewings and the predatory gall midge Aphidoletes for aphids. Convergent lady beetles and praying mantids often are not successful. For commercial crop producers, it is best to purchase technical assistance along with the product.

Promoting Natural Enemies in Your Garden

Conservation may involve establishing plants that provide alternative food sources, such as nectar and pollen for beneficial insects, or selective use of insecticides to not impair beneficial species. Many beneficial insects feed on the pollen of plants such as cilantro, fennel, Spanish needle, and buckwheat. It may be possible to increase the number of beneficial insects by including such plants in a farm or garden.

Many of the natural enemies described in this guide do not solely rely on prey. They also feed on pollen as an alternative food source. Predator insects such as ladybird beetles, hoverflies, and parasitoid wasps actively feed on pollen and nectar. These resources are particularly important for hoverflies that only feed on flowers during their adult life, for ladybird beetles that need high protein content at the end of the overwintering season, or for minute pirate bugs that need pollen for survival during the adult stage. The addition of companion plants such as sweet alyssum or marigold can potentially increase biological control services.

IPM

A pest control method is often most effective when used as a component of an integrated pest management (IPM) system. IPM involves using a variety of techniques to manage the pest in an economically viable and environmentally sound manner. IPM programs rely on the periodic examination of crops to determine if pest populations are reaching damaging levels. This is called scouting, which provides information on the relative proportion of beneficial and harmful arthropods on a crop. Effective scouting can lead to significant reductions in insecticide use because insecticides are applied only when necessary. Reduction of insecticide use is a central concern of most IPM programs, and is crucial for enhancing biological control, as natural enemies can be highly susceptible to insecticides. As insecticide use increases, populations of beneficial insects decrease, which may lead to secondary pest outbreaks. For instance, use of some pyrethroid-based insecticides is known to trigger spider mite infestations in vegetable and row crops. IPM programs which rely on the careful use of selective insecticides including Bt products, and non-insecticidal tools, such as kaolin clay or insect pheromones, may benefit from increased effectiveness of both native and introduced natural enemies.

Natural Enemies Commonly Seen in Florida

There are many insects that are beneficial, but only a few are important natural enemies of pests. The commonly encountered natural enemies are ladybird beetles, lacewings, big-eyed bugs, minute pirate bugs, flower flies, predatory gall midges, ants, parasitic wasps, parasitic flies, and predatory mites. Their relative importance varies with arthropod pest, habitat, and season of the year.

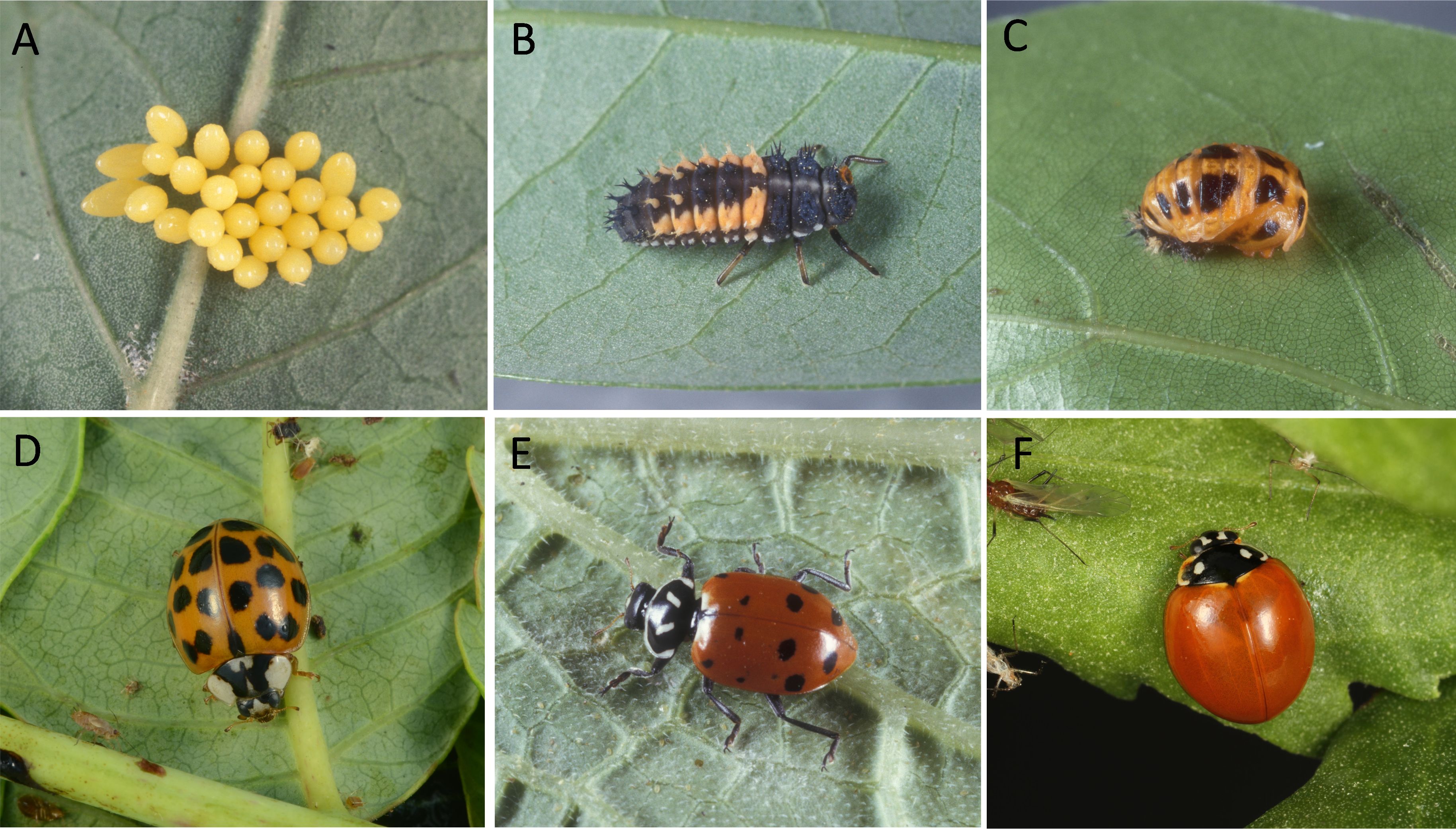

Ladybird Beetles

Adult ladybird beetles (Figure 1) are among the most recognizable insects, but only when they are the "typical" beetles — orange or red with black spots. These beetles come in many colors, including brown or black, and often lack spots, and some of them can be extremely small, less than 1/10 of an inch in length. The adult’s hemispherical shape is a helpful characteristic for identification, along with its frantic searching behavior — the adult beetles are always looking for a quick bite to eat. Larvae are more difficult to recognize, and many gardeners have killed the beneficial larvae or pupae due to an inability to identify them. The larval stage is elongated and flattened, and usually blackish or bluish with orangish spots. In addition, some lady beetle species have larvae with white, waxy exudate on their backs and resemble mealybugs. If you see a white insect crawling among aphids, it very likely is a lady beetle larva. The pupal stage is similar to the larva in color, but it is not capable of moving or feeding. Unfortunately, one of the most common lady beetles in Florida’s landscape is the exotic multicolored Asian lady beetle (Figure 1D). Similarly, the common seven-spot ladybird beetle is exotic from Europe. Florida native ladybird beetles include Hyppodamia convergens and Cycloneda sanguinea (Figure 1E and Figure 1F). The eggs are yellow and deposited in clusters. Ladybird beetles feed on numerous small insects and will attack any stage of prey that is small enough to be killed. They are most frequently found feeding among aphid colonies, but many also consume mites, scales, mealybugs, whiteflies, small caterpillars and beetle grubs, and all types of insect eggs.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

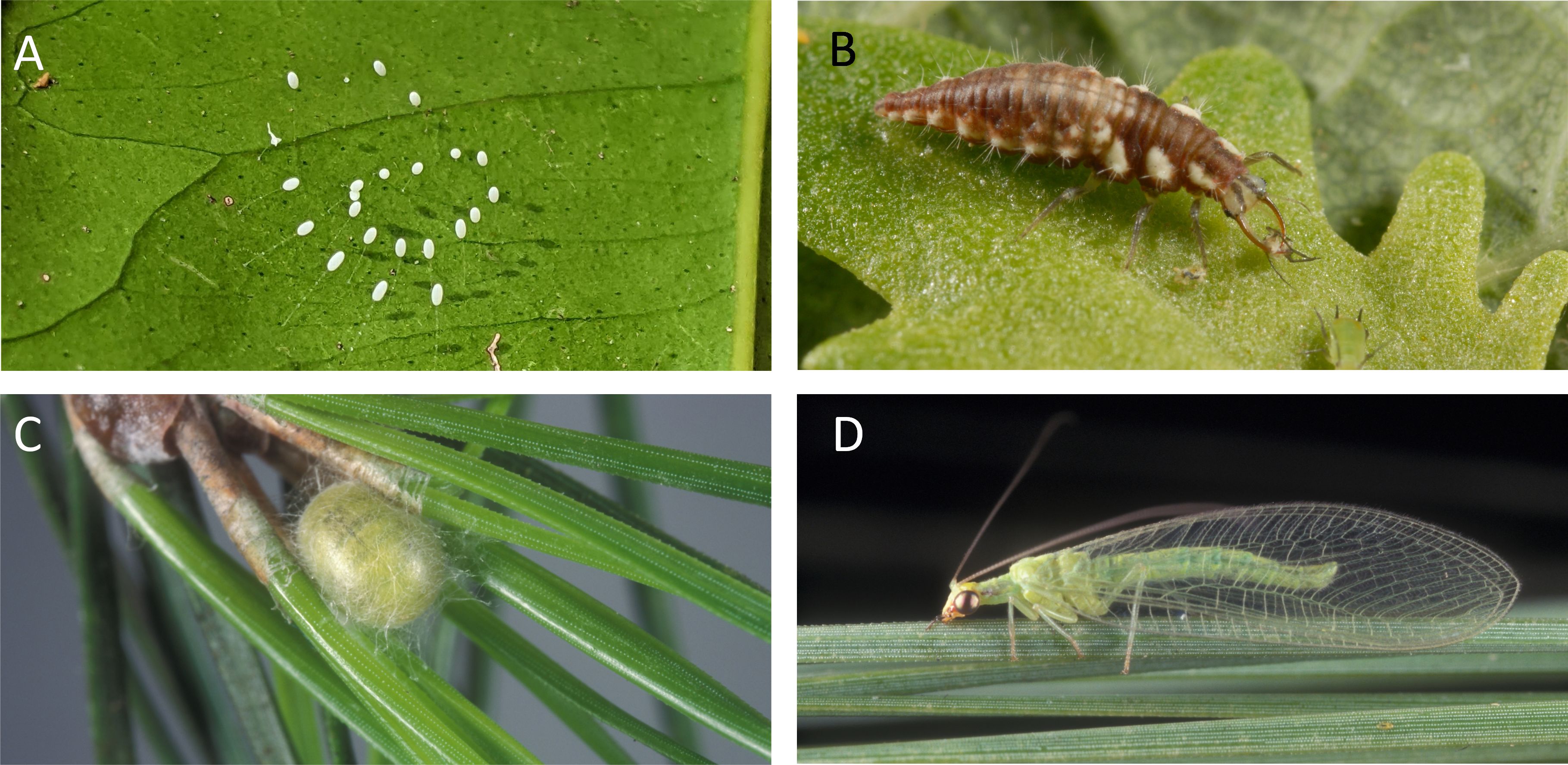

Lacewings

Both green and brown lacewings occur in Florida, and the lacy-looking adults are quite recognizable (Figure 2). Like ladybird beetles, lacewings are often found associated with aphid colonies. However, unlike ladybird beetles, the adults sometimes do not feed on insects; the larvae are the beneficial stage. The large, sickle-shaped mouthparts apparent in the larval stage are very effective for clamping onto prey and draining their body contents. The eggs of lacewings are placed on long, thin stalks in clusters. Lacewings feed on insect eggs, scales, mealybugs, and mites as well as aphids.

Credit: (A) Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS; (B, C, D) Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

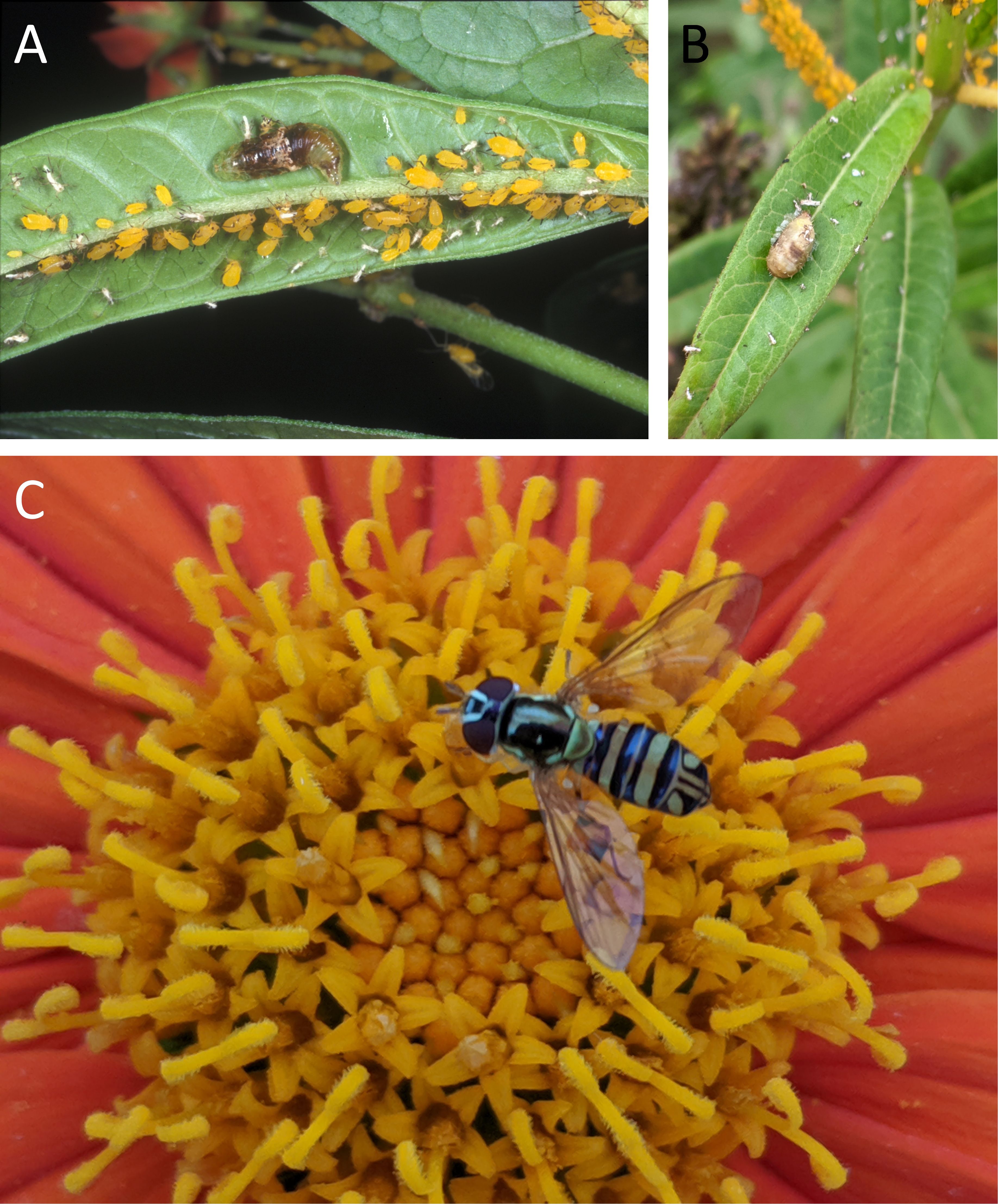

Flower Flies

Flower flies (Figure 3) are both pollinators and natural enemies. Some have bright colors that mimic wasps and may deter predators, but do not sting. Flower flies, also called hoverflies, feed on nectar and pollen as adults. The larvae of some flower flies specialize in feeding on aphids (Figure 3A). The larvae are maggot-like in appearance, with a thick body that tapers to a pointed head. They are yellowish, reddish, or greenish in color.

Credit: (A) Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS; (B, C) Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS

Predatory Gall Midges

Larvae of predatory gall midges (Figure 4) resemble flower flies and often are overlooked because they are very small. Most people who notice these larvae think they are very young flower flies. The larvae commonly are found within aphid colonies, but they also feed on whiteflies, scales, thrips, and mites. However, the adults are strikingly different. The adult gall midge is rarely observed because it is active at night, small, and pale, and with long, thin legs.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Big-Eyed Bugs

This common predator (Figure 5) is frequently found in agricultural systems. Both the adult and immature stage are marked by oversized eyes, but they are otherwise fairly nondescript, small, grayish insects. The piercing-sucking mouthparts are used to drain the fluids from moth eggs, caterpillars, thrips, and mites.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Minute Pirate Bugs

These very small insects are easily overlooked, but their importance as beneficial insects cannot be overestimated. Like big-eyed bugs, they feed greedily on many small organisms such as psocids, leafhoppers, aphids, thrips, and mites by draining body fluids with their piercing-sucking mouthparts. Adults (Figure 6) have a silvery-white and black pattern. They occur in both wild and crop environments. They are highly attracted to flowers where they feed on pollen.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

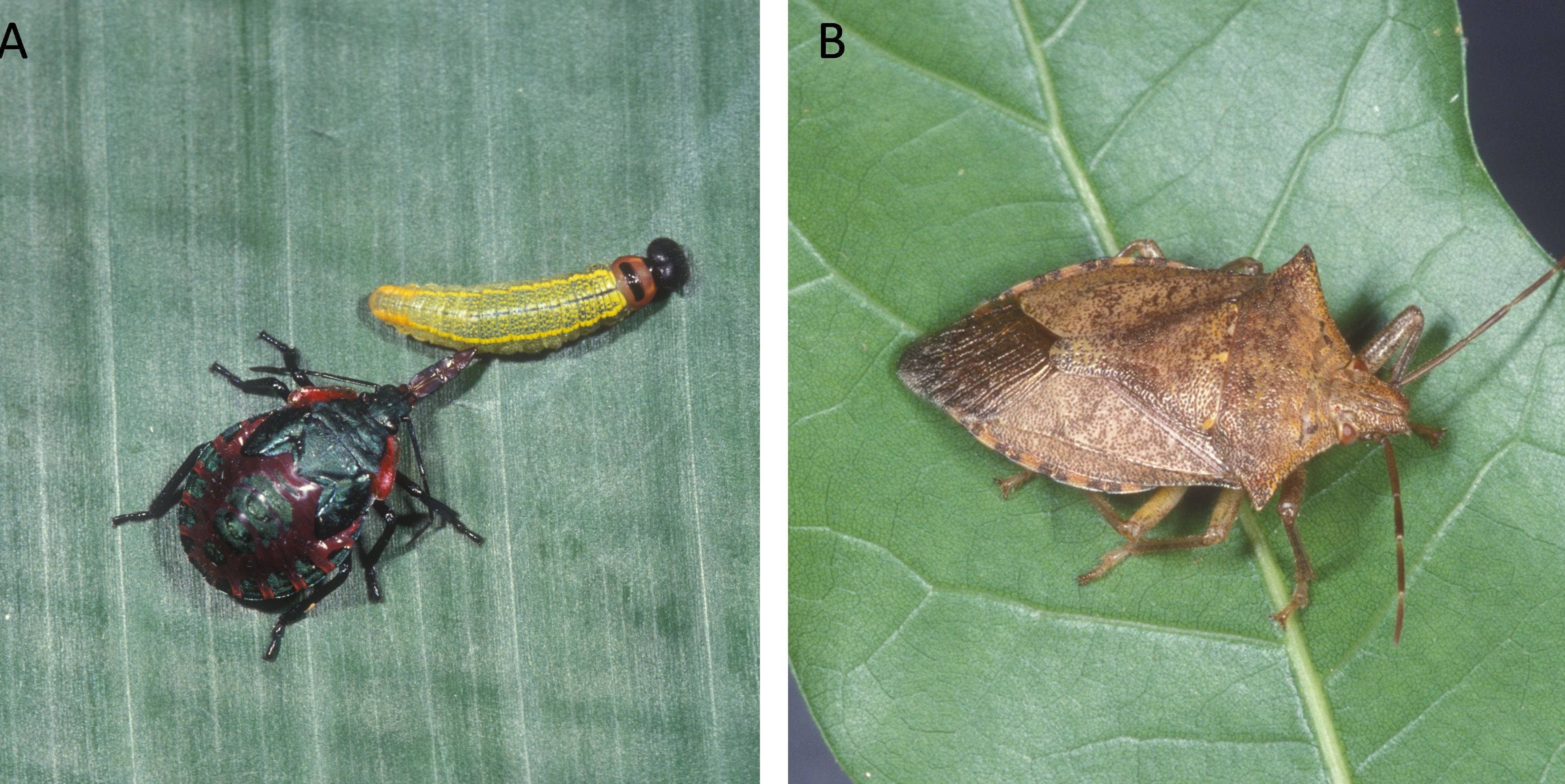

Stink Bugs

Stink bugs (Figure 7) include severe pest species as well as useful predators because different species vary in their eating habits. The most common stink bug in Florida, the southern green stink bug, attacks blossoms and fruit, causing deformity and fruit drop. How can you distinguish between “good” and “bad” stink bugs? All stink bugs have long, thin, tubular piercing-sucking mouthparts, referred to as a stylet. Predatory stink bugs have a stout stylet, which they use to extract fluid from other insects, particularly caterpillars and beetle grubs. Plant-feeding stink bugs have a narrower stylet used to extract plant sap. If in doubt, observe the bug's behavior before deciding whether it is beneficial or harmful.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Assassin Bugs

Assassin bugs are Hemiptera insects from the Reduviidae family. They are generalist predators feeding on a wide range of invertebrate prey in the garden such as mosquitoes, flies, earthworms, cucumber beetles, and caterpillars. One of Florida's most common assassin bugs is the so-called milkweed assassin bug (Figure 8), Zelus longipes. The coloration of this insect varies from orange-brown to entirely black. Size ranges from 2/3 inch to ¾ inch. Assassin bugs paralyze their prey by inserting their stylets into the host body, then releasing enzymes into their prey to dissolve the host's tissue. Assassin bugs can feed on prey that may be up to six times their size.

Credit: Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS

Ants

People are often surprised to hear that some ants are important predators. Even fire ants (Figure 9) can help reduce the number of pest insects. Farmers who have fire ant problems rarely have problems with caterpillars and other soft-bodied pests! However, ants are not entirely beneficial; in addition to their tendency to bite or sting, ants sometimes protect honeydew-producing insects, such as aphids and scales, from predation and parasitism. They can also directly damage a plant’s root system by feeding on it. Thus, ants are a mixed blessing, depending on the type of plants and pests present.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Parasitic Wasps

Most parasitic wasps are small and inconspicuous, but wasps that parasitize insect eggs are even smaller, almost microscopic in size. Growers and gardeners are therefore often unaware that parasitoids are helping control their insect pests. Sometimes these wasps can be seen walking quickly over a leaf and tapping its surface with their antennae in search of the "scent" of the host. Parasitic wasps deposit their eggs on or in host insects (Figure 10) — usually the host egg or larval stage. The young parasite develops within or outside of the host insect (Figure 11), eventually killing it. The most common evidence of parasitism is often a sickly caterpillar from which parasitoid larvae are emerging or a dead caterpillar from which a cocoon is hanging. Parasitic wasps are important natural enemies of caterpillars, grubs, whiteflies, and aphids.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Parasitic Flies

Several types of parasitic flies attack pests. Many deposit their eggs (Figure 12) on the surface of the pest; upon hatching, the larva burrows into and eventually kills the host insect. However, flies lack the long egg-depositing structure found in most wasps (Figure 13).

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Predatory Mites

Although some mites, particularly spider mites, are known as serious plant pests, many mites are beneficial. Among the beneficial mites, phytoseiid mites are especially important because they are predators of plant-feeding mites and other small organisms such as thrips or insect eggs. Predatory mites (Figure 14) tend to be larger than other mites, long-legged, and more active in their search for prey.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Rosy Wolf Snail

The rosy wolf snail (Figure 15) is a Florida native predatory terrestrial snail that feeds on a variety of terrestrial mollusks, including slugs and snails. They are usually larger than non-predatory snails and have a gray to brown body, and the shell tapers at both ends and is brownish to pink. This species has been introduced in Hawaii and other Polynesian islands to feed on the African land snail, but it was found to prefer small snails, including natives. It is considered a pest on these islands. Rosy wolf snails should not be shipped or moved outside Florida.

Credit: Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS

Other Sources of Information

Other excellent sources of information include the following.

- “Guidelines for Purchasing and Using Commercial Natural Enemies and Biopesticides in North America” (Ask IFAS): https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN849

- Natural Enemies Handbook (University of California Pub. 3386, 154 pp.; 1998)

- Natural Enemies of Vegetable Insect Pests (Cornell Extension Pub., 48 pp.; 1993)

- Association of Natural Biocontrol Producers: http://www.anbp.org/

- Knowing and Recognizing: The Biology of Pests, Diseases, and Their Natural Solutions