Introduction

The lovebug, Plecia nearctica Hardy, is a bibionid fly species that motorists may encounter as a serious nuisance when traveling in southern states. It was first described by Hardy (1940) from Galveston, Texas. At that time he reported it to be widely spread, but more common in Texas and Louisiana than other Gulf Coast states.

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Credit: Debra Young, used with permission

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Within Florida, this fly was first collected in 1949 in Escambia County, the westernmost county of the Florida panhandle. Today, it is found throughout Florida. With numerous variations, it is a widely held myth that University of Florida entomologists introduced this species into Florida. However, Buschman (1976) documented the progressive movement of this fly species around the Gulf Coast into Florida. Research was conducted by University of Florida and US Department of Agriculture entomologists only after the lovebug was well established in Florida.

Classification

Thompson (1975) reported over 200 species in the genus Plecia. However, there are only two species of Plecia in the US—Plecia nearctica and Plecia americana Hardy. Their ranges are similar, but Plecia americana extends northeastward to North Carolina and south to Mexico, whereas Plecia nearctica ranges farther south to Costa Rica. Plecia americana is a woodland species that does not seem to be a problem on highways. Before Hardy described the lovebug species as Plecia nearctica, it was known as Plecia bicolor Bellardi (Hetrick 1970a).

Distribution

Plecia nearctica is established in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and the southeastern US (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas). In 2006, this species was reported as far north as Wilmington, North Carolina (Mousseau 2006).

Description and Biology

Lovebugs are small black flies with a dull, somewhat velvety appearance, except that the top of the thorax (the area immediately behind the head) is red. Males are 6–7 mm (~1/4 in), and females are 6–9 mm (~1/4 to 1/3 in) in length and vary considerably in size as males weigh 6 to 10 mg (0.0002 to 0.00035 oz) and females 15 to 25 mg (0.0005 to 0.0009 oz). The weight difference between sexes is largely due to the ovaries, which contain 70 percent of the total protein. Neither sex has the ability to store lipids in fat body cells (Van Handel 1976). See a more detailed, scientific description in Key to the Species.

Hetrick (1970a) stated that adult males live for two to three days and females can live for a week or longer and mate with more than one male. However, Thornhill (1976c) recorded recapture data that showed males lived longer in the field than females. In his study, single females were collected up to four days after release while single males were collected five days after release.

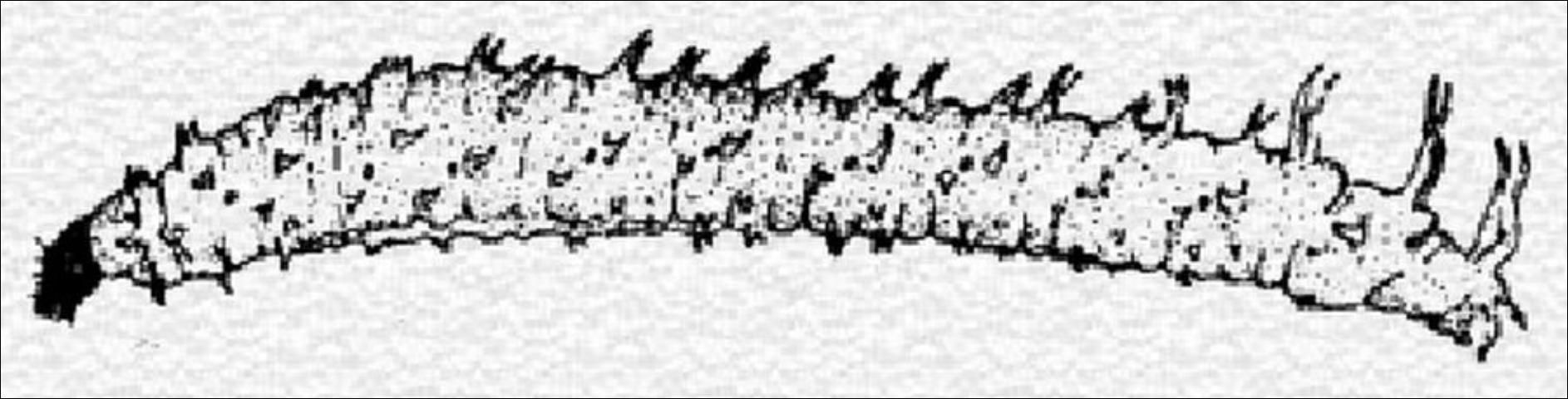

The females lay gray, irregularly shaped eggs in or on the soil surface under partially decayed vegetable matter. Slate-gray larvae are often found in groups beneath decaying vegetation, where moisture is consistent. Factors necessary for larval survival include adequate moisture, partially decayed vegetation (for food), and favorable soil temperatures. Pupation occurs where the larvae develop, with the pupal stage lasting seven to nine days (Hatrick 1970a).

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Each of the two Plecia nearctica generations in Florida lasts about four weeks in April–May and August–September. In addition to the two large emergences, this species has been collected in Florida every month of the year except November (Buschman 1976). A more recent study by Cherry and Raid (2000) shows a minor flight peak in December for south Florida that had been previously unrecorded. This later study does not contradict the importance of the two major flight peaks earlier in the year, but does state that in south Florida most of the adults seem to appear in April during the first yearly flight.

Buschman (1976) stated that, throughout its extensive range, Plecia americana has been collected only in April, May, and June, with no evidence of a fall emergence. Thus, Plecia that emerge in the fall are definitely Plecia nearctica. Thompson (1975) added that most of the spring collection dates of Plecia americana in north central Florida are two or three weeks earlier than similar dates for Plecia nearctica.

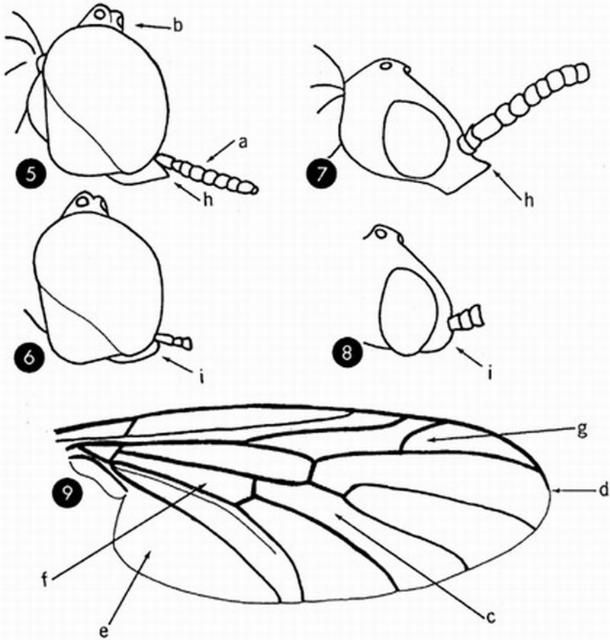

Key to the Species

Thompson (1975) illustrated and prepared a key for the two species of Plecia that occur in the US. His key and illustrations are used here with his permission.

1. Thorax with dorsum rufous and pleura extensively black; head with oral margin distinctly produced forward. Male genitalia with 9th tergum not as broad as in Plecia americana, just slightly broader than long, with shallow medial excavation and ventromedial flap, not produced ventrolaterally; 9th sternum with dorsolateral lobe extending under 9th tergum, produced ventromedially into a narrow, forked process; telomeres large, L- shaped in lateral view. Female genitalia with 9th tergum large, almost completely concealing cerci in lateral view, strongly excavated dorsomedially; cerci small, narrow in dorsal view; 8th sternum small, with a shallow medial excavation; ovipositor lobes broad, blunt apically and strongly sclerotized dorsally . . . . . lovebug, Plecia nearctica Hardy

1'. Thorax almost completely rufous, rarely slightly brownish black on metathoracic pleura; head with oral margin not produced forward, but evenly convex. Male genitalia with 9th tergum much broader than in Plecia nearctica, almost twice as broad as long, with a deep medial excavation and without a ventromedial flap, ventrolateral corners produced posteriorly; 9th sternum with a dorsolateral lobe, not produced ventromedially and without a medial forked process, but with a broad ventromedial excavation. Female genitalia with 9th tergum small, not concealing cerci in lateral view, not excavated medially; cerci large, broad in dorsal view; 8th sternum large, with a deep and narrow medial excavation; ovipositor lobes narrow, acute apically, not strongly sclerotized dorsally . . . . . Plecia americana Hardy

Credit: F. C. Thompson, UF/IFAS

Credit: F. C. Thompson, UF/IFAS

Credit: F. C. Thompson, UF/IFAS

Dilophus sayi

Another March fly (Bibionidae) that may be confused with Plecia neartica is Dilophus sayi Hardy (1966). The behavior of the adults is somewhat similar to that of Plecia nearctica, but Dilophus sayi adults do not congregate on highways. In Florida, Dilophus sayi populations peak from late January through April, but can be observed most of the year beginning with cooler weather in October. Most Florida records are in the peninsula south to Dade County.

Dilophus sayi is smaller than the Plecia spp., and has an all-black body, lacking the reddish color of the thoracic region of Plecia. The males of Dilophus sayi are smaller than the females and have clear wings as opposed to the brown fumose wings of the females.

Dilopus sayi was observed being attracted to recently parked cars in Gainesville, Florida, and to barbecue grills (Denmark and Mead, personal observations). Thornhill (1976a) in studies at Gainesville, Florida, stated that aggregates of up to 300 larvae of Dilophus sayi could be found on or near the surface of the soil among the roots of grasses. Under lab conditions, adult females lived about 72 hours and adult males about 92. Both Thornhill and Rothamel (1969) gave details on orientation and coupling of Dilophus sayi. This bibionid attains nuisance numbers as adults in Florida and elsewhere from South Carolina south and west to Texas and California. Complaints about the larvae and adults of Dilophus sayi (reported as Dilophus orbatus, an earlier name) were statewide in California during October of 1970 (USDA Cooperative Economic Insect Report 20797). In this same volume, there were numerous reports of it being a problem during autumn in sod and lawns, including one report of 1,000 larvae per square meter in a nursery at Oakland, Alameda County, California. However, this species is of minor importance compared to Plecia nearctica, which can be a nuisance on roads in the southeastern United States.

Behavior of Plecia nearctica

Hetrick (1970a) studied the biology of Plecia nearctica, and estimated that September 1969 flights reached altitudes of 300 to 450 m (984 to 1476 ft) , extended several kilometers over the Gulf of Mexico and covered one-fourth the land area of Florida.

Callahan and Denmark (1973) reported that ambient temperatures above 28°C (82.4°F) and visible light at above 20,000 Lux (2000 ft-C) stimulated lovebug flight but not orientation behavior. Lovebugs are attracted to irradiated automobile exhaust fumes (diesel and gasoline) when the ultraviolet light incident over the highway ranges from 0.3 to 0.4 microns (3000 to 4000 angstroms (A)) between 10 AM and 4 PM, with a temperature above 28°C. Hot engines and the vibrations of automobiles apparently contribute to the attraction of lovebugs to highways. Callahan et al. (1985) reported that formaldehyde and heptaldehyde were the two most attractive components of diesel exhaust.

The following description of reproductive behavior was taken largely from Leppla et al. (1974), who reported on a daily rhythmicity of flight, mating, and feeding of lovebugs in the laboratory and in the field, which coincided with the ambient temperature of 19°C (66.2°F) and an incident light intensity range of 15,000 to 20,000 Lux (1500-2000 ft-C). Adult males begin hovering between 8:00 to 10:00 AM EDT. Males orient into the wind 0.3 to 0.9 m (~1 to 3 ft) above ground level. This behavior tends to cease after 10 AM and a resurgence occurs at 4:00 to 5:00 PM and lasts until about 8:00 PM. Females do nor hover but crawl up vegetation and take flight through the swarm of hovering males. The female is grasped by a male during flight, or while she is on vegetation before flight. Copulating pairs begin dispersal flights around 9 to 11 AM. Individuals may feed alone, or while in copula, on nectar or pollen in the vicinity of the emergence site. There are few or no mating pair flights by afternoon.

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Hosts

The larvae develop under and feed on dead, partially decayed plant material, particularly in moist to damp areas and in pastures under cow manure. Buschman (1976) stated that the largest populations of Plecia neartica were found in grassy habitats such as Bahia grass, Paspalum spp., pastures and roadsides.

Other habitats recorded for populations of Plecia americana include live oak hammocks, wooded ravines, and deciduous forests.

Economic Importance of Plecia neartica

Plecia nearctica is beneficial in the larval stages by helping to recycle decaying vegetative matter into organic matter (Hetrick 1970a).

The adult flies are a nuisance to motorists because the flies are attracted to highways and spatter on the hood and windshield of vehicles. Large number of lovebugs can cause overheating of liquid-cooled engines by clogging radiators. They can also reduce visibility and etch automobile paint as the body fluids are slightly acidic. If the egg mass and body parts are allowed to remain on the vehicle for several days, bacterial action increases the acidity and etches the paint. A soaking with water for about five minutes followed by a scrubbing within 15 to 20 minutes should remove most of the lovebugs without harm to automobile paint.

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Fortunately, improvements in vehicle paint coatings have made this less of a problem. A hood air deflector will reduce the number of spattered lovebugs on a vehicle. In addition, specially designed nylon screening, with hooks that attach to the front of vehicle bodies, are commercially available at automotive supply stores. The screens catch the flies, preventing radiator clogging and splattering on the vehicle body.

The adults seem to be attracted to light-colored surfaces, especially if the surfaces are freshly painted.

Credit: Debra Young, used with permission

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Debra Young, used with permission

Management

Local reduction of annual burning of woodlands, the development of improved pastures, and the increase of cattle probably have contributed to the presence of larger populations of lovebugs. Chemical controls are ineffective as the lovebug is widespread and adults continually drift onto highways from adjacent areas.

The degree of natural control and the amount of annual rainfall causes fluctuation in populations.

Kish et al. (1974) isolated and identified five species of fungi from dead lovebugs collected in Florida during April and May. These fungi were:

- Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill,

- Tolypocladium cylindrosporum W. Gams,

- Metarrhizium anisopliae (Metsch.) Sorok,

- Apiosordaria verruculosa (Jensen) von Arx and W. Gams,

- Eupenicillium brefeldianum (Dodge) Stolk & Scott.

Two species of fungi collected in the Fall were:

- Conidiobolus coronatus (Cost.) Batko,

- Arthrobotrys oligospora Fres.

Tests demonstrated that each fungus apparently affected larval mortality. However, data analyses indicated that only Beauveria bassiana caused significant mortality levels (27 to 33%) in adults and immatures (Kish et al. 1977).

Nine additional fungi were reported from dead or moribund larvae collected in the field. These fungi are likely important in the natural control of lovebugs (Kish et al. 1977). Further study is needed to determine how these fungi or other organisms may be used to control lovebugs.

Selected References

Buschman LL. 1976. Invasion of Florida by the "lovebug," Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae). Florida Entomologist 59: 191–194.

Callahan PS, Carlysle TC, Denmark HA. 1985. Mechanism of attraction of the lovebug, Plecia nearctica, to southern highways: further evidence for the IR-dielectric waveguide theory of insect olfaction. Applied Optics 24: 1088–1093.

Callahan PS, Denmark HA. 1973. Attraction of the "lovebug," Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae) to UV irradiated automobile exhaust fumes. Florida Entomologist 56: 113–119.

Callahan PS, Denmark HA. 1974. The "lovebug" phenomenon. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Conference on Ecological Animal Control by Habitat Management (March 1973). 5: 93–101.

Chambers SM. 1977. Genetic characteristics of a colonizing episode in the lovebug, Plecia nearctica. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 70: 537–540.

Cherry R. 1998. Attraction of the lovebug, Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae), to anethole. Florida Entomologist 81: 559–562.

Cherry R, Raid R. 2000. Seasonal flight of Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae) in southern Florida. Florida Entomologist 83: 94–96.

Evans HE. 1985. The lovebug. In The Pleasures of Entomology. Portraits of Insects and the People who Study Them. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 238 pp.

Fasulo TR, Kern W, Koehler PG, Short DE. 2005. Pests In and Around the Home. Version 2.0. University of Florida/IFAS. CD-ROM. SW 126.

Hardy DE. 1940. Studies in New World Plecia (Bibionidae: Diptera). Part I. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 13: 15–27.

Hardy DE. 1945. Revision of Nearctic Bibionidae including Neotropical Plecia and Penthetria (Diptera). University of Kansas Science Bulletin 30, Pt. II, No. 15: 367–547.

Hardy DE. 1966. Family Bibionidae. In A Catalog of the Diptera of the Americas South of the United States. Departmento de Zoologia, Secretaria da Agricultura, Sào Paulo. 18: 1–20.

Hetrick LA. 1970a. Biology of the "love-bug," Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae). Florida Entomologist 53: 23–26.

Hetrick LA. 1970b. The "love-bug," Plecia nearctica Hardy (Diptera: Bibionidae). FDACS-DPI. Entomology Circular 102. Hieber CS, Cohen JA. 1983. Sexual selection in the lovebug, Plecia nearctica: The role of male choice. Evolution 37: 987–992.

Kish LP, Allen GE, Kimbrough JW, Kuitert LC. 1974. A survey of fungi associated with the lovebug, Plecia nearctica, in Florida. Florida Entomologist 57: 281–284.

Kish LP, Terry I, Allen GE. 1977. Three fungi tested against the lovebug, Plecia nearctica, in Florida. Florida Entomologist 60: 291–295.

Kuitert LC. 1975. Sexual dimorphism in Plecia nearctica pupae (Diptera: Bibionidae). Note. Florida Entomologist 58: 212.

Leppla NC. (2007). Living with Lovebugs. EDIS. (13 April 2015).

Leppla NC, Carlysle TC, Guy RH. 1975. Reproductive systems and the mechanics of copulation in Plecia nearctica Hardy (Diptera: Bibionidae). International Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 4: 299–306.

Leppla NC, Sharp JL, Turner WK, Hamilton EW, Bennett DR. 1974. Rhythmic activity of Plecia nearctica. Environmental Entomology 3: 323–326.

Mousseau TA. (2006). Love Bugs on the Move. (13 April 2015).

Rotramel G. 1969. Orientation and coupling in Dilophus orbatus (Diptera: Bibionidae). Pan-Pacific Entomologist 45: 74.

Sharp JL, Leppla NC, Bennett DR, Turner WK, Hamilton EW. 1974. Flight ability of Plecia nearctica in the laboratory. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 67: 735–738.

Short DE. (2003). Lovebugs in Florida. EDIS. (13 April 2015).

Thompson FC. 1975. "Lovebugs," a review of the nearctic species of Plecia (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Bibionidae). U.S.D.A., Cooperative Economic Insect Report. 25: 87–91.

Thornhill R. 1976a. Biology and reproductive behavior of Dilophus sayi (Diptera: Bibionidae). Florida Entomologist 59: 1–4.

Thornhill R. 1976b. Reproductive behavior of the lovebug, Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 69: 843–847.

Thornhill R. 1976c. Dispersal of Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae). Florida Entomologist 59: 45–53.

Trimble JJ. 1974. Ultrastructure of the ejaculatory duct region of the lovebug, Plecia nearctica Hardy. International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology 3: 353–359.

Van Handel E. 1976. Metabolism of the "lovebug" Plecia nearctica (Diptera: Bibionidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 69: 215–216.

Whitesell JJ. 1974. Heat, sound, and engine exhaust as "lovebug" attractants (Diptera: Bibionidae: Plecia nearctica). Environmental Entomology 3: 1038–1039.