Belonolaimus longicaudatus Rau (Nematoda: Secernentea: Tylenchida: Tylenchina: Belonolaimidae: Belonolaiminae)

The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

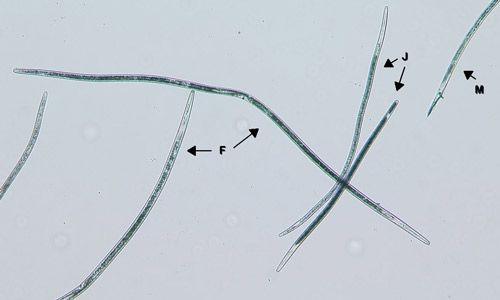

The common name sting nematode is generally applied to nematodes in the genus Belonolaimus, particularly Belonolaimus longicaudatus (Figure 1), although it is also being applied to the closely related genera Morulaimus and Ibipora in Australia. Belonolaimus longicaudatus is among the most destructive plant-parasitic nematodes to a wide range of plants including turfgrasses, ornamentals, forages, vegetables, agronomic crops, and trees. Feeding by Belonolaimus longicaudatus causes damage to plant roots and limits the ability of roots to take up water and nutrients from the soil. This causes plants to become stunted, wilt, and with severe infestation, die. Florida is considered to be the point-of-origin for Belonolaimus longicaudatus and therefore this nematode exhibits a great deal of diversity in morphology, host preference, and genetics in our region. All indications are that Belonolaimus longicaudatus is paraphyletic, meaning that there are multiple species that are being grouped artificially into a single species.

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Distribution

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is native to the sandy coastal plains of the southeastern United States. It is limited to soils with high sand content (>80% sand) and is common in sandy regions along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts from Texas to Virginia. Belonolaimus longicaudatus has been spread to sandy areas inland, mostly with infested soil and plant material, and has been found as far north as southern Ohio. It has been spread on infested golf course sod to California, and to several islands in the Caribbean. An undescribed species of Belonolaimus, morphologically similar to Belonolaimus longicaudatus, has been found infesting turfgrasses west of the Mississippi river in Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Life Cycle and Biology

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is an ectoparasite, meaning that its entire life cycle is spent in the soil and it feeds on plant roots from the outside. Eggs are laid in pairs by the female nematode as rapidly as 10 eggs per 10–15 hours. After a few days, the second-stage juvenile hatches from the egg. The juvenile nematode feed on root hairs, and as it matures it will begin to feed on root tips. It will undergo three additional molts into a third-stage juvenile, fourth-stage juvenile, and finally into an adult nematode. The juvenile stages are similar to each other and to the adults, differing only in size and the presence of sexual organs in adults (Figure 2).

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

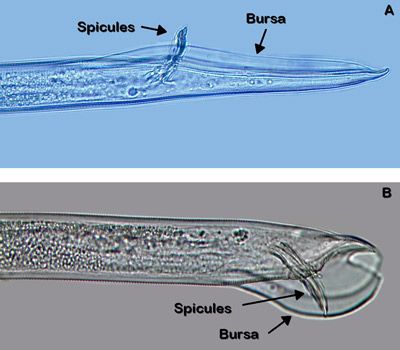

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is an amphimictic and gonochoristic species, meaning that it employs sexual reproduction between distinct males and females. Paired male organs called spicules (Figure 3) are inserted into the vagina (Figure 4) of the female to deposit sperm. Copulation is aided by paired cuticular flaps called the bursa on the male (Figure 3). Mating only needs to occur once because the female nematode stores the sperm in an organ called a spermatheca. Depending on conditions and population, development from an egg to an egg-laying adult takes between 18 and 24 days.

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. E. Luc, UF/IFAS

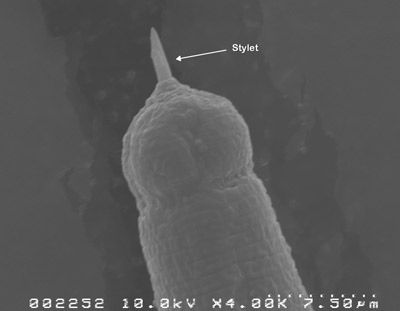

Belonolaimus longicaudatus has a long stylet that it uses to feed. The stylet functions like a hypodermic needle that can be used to inject substances into plant cells and also to remove plant cell contents (Figure 5). It inserts its stylet into the meristematic tissue of root tips and injects digestive enzymes prior to ingestion. This causes death of the root meristem. A video of Belonolaimus longicaudatus feeding on a root tip can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTWGocLhMtU.

Credit: J. E. Luc, UF/IFAS

Importance

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is considered the most damaging nematode to turfgrasses, forage grasses, strawberry, potato, sugarcane, and cantaloupe in Florida. It also can cause major damage on many other agronomic, horticultural, forage, and tree crops. To avoid severe crop losses from Belonolaimus longicaudatus, chemical nematicides or crop rotations are commonly used. Belonolaimus longicaudatus is a Class A quarantine pest in California, and any plant shipments containing Belonolaimus longicaudatus are banned from that state. Similarly, Belonolaimus longicaudatus is a quarantine pest in many countries and can greatly impact movement of plant and soil material internationally.

Symptoms

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is among the most damaging of all plant-parasitic nematodes. Feeding by this nematode kills the root meristem and halts root growth. Lateral roots will develop, but Belonolaimus longicaudatus will migrate to these lateral roots and damage them as well. This causes an abbreviated and stubby-looking root system (Figures 6 and 7). Turfgrass roots may appear cropped off just below the thatch (Figure 8). Because the roots are damaged, they are unable to supply the plant with water and nutrients. Damaged annuals will become stunted, wilt, and die (Figure 9). Young citrus trees infected by Belonolaimus longicaudatus may require extra years after planting before bearing fruit. Corn and cane may lodge (fall over) as the nematodes damage their brace-roots. Turfgrasses may wilt (Figure 10) and decline, and weeds may proliferate (Figure 11). Damage from Belonolaimus longicaudatus typically occurs in patches because the nematodes are generally clumped in distribution (Figures 12, 13, and 14).

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. Hamill, University of Florida

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. Hamill, UF/IFAS

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Hosts

Belonolaimus longicaudatus has a wide host range and feeds on many wild and cultivated plants. A partial list of cultivated hosts in Florida include turfgrasses (St. Augustinegrass, bermudagrass, zoysia, centipede, seashore paspalum), grains and forage grasses (corn, sorghum, rye, sugarcane, millet, sudangrass, bahiagrass, oats, wheat, Pangola digitgrass), leguminous forages (clover, alfalfa, alyce clover), agronomic crops (cotton, potato, soybean), small fruits and vegetables (strawberry, beans, cabbage, pepper, cantaloupe). Known weed hosts include Carolina geranium, black medic, crabgrass, Spanish needle, ragweed, and many others.

Different populations of Belonolaimus longicaudatus have different host ranges; some populations are capable of parasitizing plants that others cannot. Examples of plants that only certain Florida populations of Belonolaimus longicaudatus can parasitize include: citrus, watermelon, peanut, and cucumber.

Identification

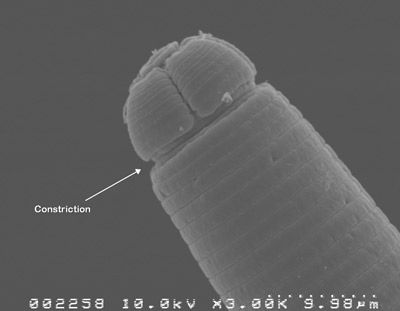

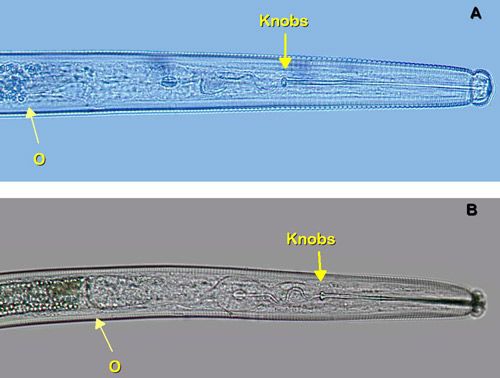

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is a very long (2–3 mm) and slender (40 µm) nematode. The stylet is also long (>100 µm) and slender with rounded knobs (Figure 14). The anterior region is offset by a prominent constriction (Figure 15).

Credit: J. E. Luc, UF/IFAS

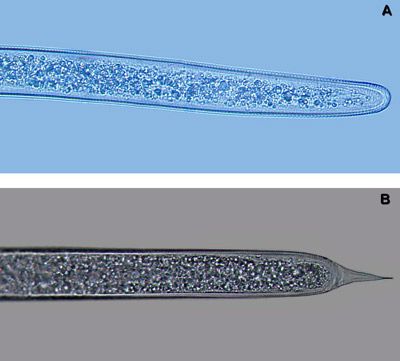

The most similar nematode genus in appearance to Belonolaimus spp. in Florida is Dolichodorus spp. These are both common nematode genera that share many of the same hosts and can occur concomitantly. The features that most easily distinguish these two genera are: i) the esophageal glands of Belonolaimus overlap the intestine, those of Dolichodorus do not (Figure 16), ii) the tail of juveniles and females of Belonolaimus are rounded, those of Dolichodorus have a pointed tip (Figure 17), and c) males of Belonolaimus have a long, narrow bursa, the bursa of Dolichodorus is wide and round (Figure 3).

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Credit: W. T. Crow, UF/IFAS

Belonolaimus longicaudatus is separated from other Belonolaimus spp. by i) having a single lateral incisure (Figure 18), ii) the cephalic constriction is pronounced in both sexes (Figure 15), iii) vulva with no protruding lips (Figure 4), and iv) presence of sclerotized vaginal pieces (Figure 4). While Belonolaimus longicaudatus was originally characterized by having a stylet shorter than its tail, this feature has since been found to be highly variable and not a reliable diagnostic feature.

Credit: J. E. Luc, UF/IFAS

Management

Because Belonolaimus longicaudatus is an ectoparasite that spends its entire life in soil, it is among the most responsive plant-parasitic nematodes to fumigant and nematicide treatments. Despite this, it is difficult to manage with chemicals in certain systems due to its seasonal vertical migration. In Florida strawberry production, a portion of the Belonolaimus longicaudatus population will migrate deep in the soil profile during fallow and field preparation, allowing these nematodes to escape fumigation in the upper portions. Similarly, in turf systems Belonolaimus longicaudatus will migrate deeper in the soil during the summer months, limiting the effectiveness of nematicides applied to the turf surface during that time.

Because Belonolaimus longicaudatus has no long-term survival stage, its numbers will rapidly decline from starvation during extended periods of clean fallow, or rotation with a non-host crop. However, the wide range of host plants for Belonolaimus longicaudatus makes it difficult to select non-host rotation crops or cover crops. Sunn hemp has been shown to be resistant to Belonolaimus longicaudatus and may be used as a summer cover crop for suppression of Belonolaimus longicaudatus and other plant-parasitic nematodes in some situations. In strawberry it is important to kill off the plants after harvest so that they do not maintain the nematode population. Weed management is very important to eliminate all Belonolaimus longicaudatus hosts during fallow or rotation.

Recent breeding efforts for strawberry and turfgrass have emphasized selection of genotypes that are resistant or tolerant to Belonolaimus longicaudatus. Hopefully these efforts will lead to less susceptible cultivars that may be used in Integrated Pest Management for Belonolaimus longicaudatus in the future. Currently, 'Celebration' bermudagrass has exhibited tolerance to Belonolaimus longicaudatus and is recommended for lawns, athletic fields, and golf course fairways infested by Belonolaimus longicaudatus in Florida. For up-to-date information on management of Belonolaimus longicaudatus and other plant-parasitic nematodes on specific crops in Florida go to the Florida Nematode Management Guide.

Selected References

Cid Del Prado Vera I, Subbotin SA. 2012. "Belonolaimus maluceroi sp.n. (Tylechida: Belonolaimidae) from a tropical forest in Mexico and key to the species of Belonolaimus." Nematropica 42: 201–210.

Crow WT, Han HR. 2005. Sting nematode. Plant Health Instructor: DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2005-1208-01. http://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/Nematodes/Pages/StingNematode.aspx

Gozel U, Adams BJ, Nguyen KB, Inserra RN, Giblin-Davis RM, Duncan LW. 2006. "A phylogeny of Belonolaimus populations in Florida inferred from DNA sequences." Nematropica 36: 155–171.

Han HR, Dickson DW, Weingartner DP. 2006. "Biological characterization of five isolates of Belonolaimus longicaudatus." Nematropica 36: 25–35.

Han HR, Jeyaprakash A, Weingartner DP, Dickson DW. 2006. "Morphological and molecular biological characterization of Belonolaimus longicaudatus." Nematropica 36: 37–52.

Smart GC, Nguyen KB. 1991. Sting and awl nematodes. Pp. 627–668 In Nickle WR ed., Manual of agricultural nematology. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc.