Each year thousands of dogs become disabled or die from lung, heart, or circulatory problems caused by heartworm disease. Heartworm disease in dogs and related canines is caused by a filarial nematode (a large thread-like round worm), Dirofilaria immitis. The adult worms live in the right side of the heart in the right ventricle and adjacent blood vessels (pulmonary arteries). Because of their location, they are commonly called "dog heartworms."

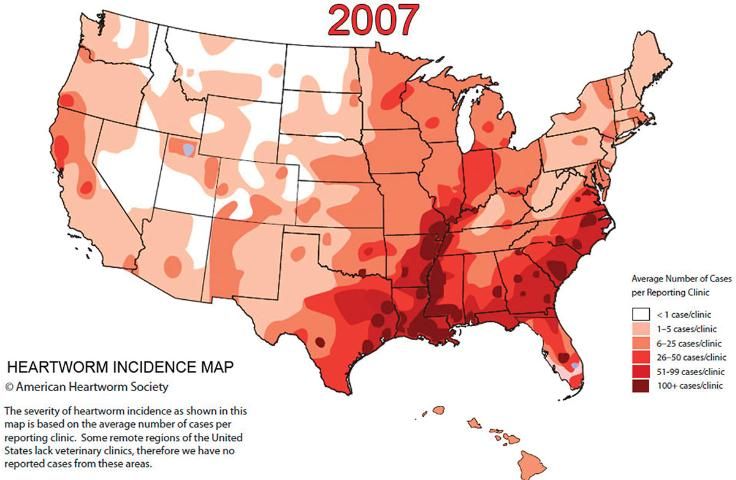

Distribution of Heartworm Disease

Heartworm disease occurs worldwide in tropical, subtropical, and some temperate regions. Until the late 1960s, the disease was restricted to southern and eastern coastal regions of the United States. Now, however, cases have been reported from dogs native to all 50 states (Figure 2). For most of North America, the danger of infection is greatest during the summer when temperatures are favorable for mosquito breeding. In the southern United States, especially the Gulf Coast and Florida, where mosquitoes are present year-round, the threat of heartworm disease is constant.

Credit: American Heartworm Society

The Heartworm Parasite

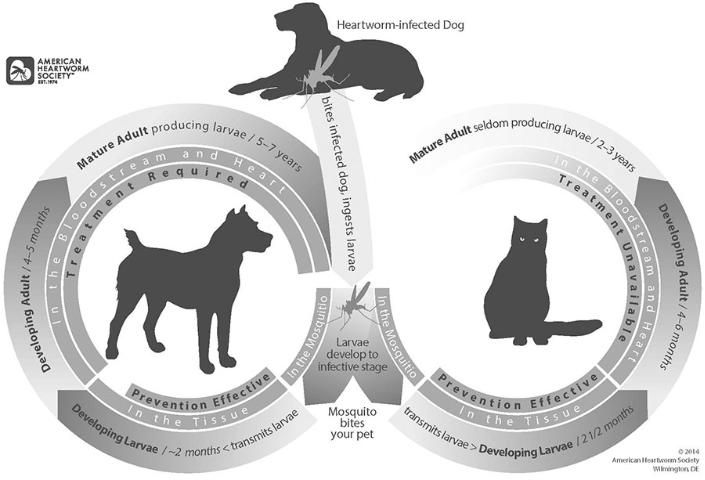

The complete development of the nematode parasite requires two hosts: dog and mosquito (Figure 3). In the dog, sexually mature adult nematodes are large (females up to 14 inches and males up to 7 inches) and cause disease by clogging the heart and major blood vessels leading from the heart. By clogging the main blood vessels, the blood supply to other organs of the body is reduced, particularly the lungs, liver, and kidneys, leading to malfunction of these organs. Once infected, a dog is infected for life. The sexually mature nematodes discharge tiny (less than 1/800" inch long) immature worms called microfilariae into the bloodstream of a dog. They do not develop further in the dog, but they can survive in the blood for up to three years. They must be ingested by a mosquito before they can progress further in their development. There are more microfilariae in the blood during the day than at night. Optimum numbers of microfilariae in the blood close to the skin coincide with times of peak feeding activity of mosquitoes. Microfilariae may also be more abundant in the summer when mosquitoes are abundant.

Development in the Mosquito

Development of heartworm in the vector starts when microfilariae are ingested by the female mosquito during blood feeding on an infected dog. Microfilariae leave the midgut of the mosquito soon after ingestion and migrate into the Malpighian tubule cells (the mosquito kidney). At a temperature of about 27°C. the parasite becomes immobile, shortens and thickens, and develops into the so-called "sausage form" larva in about four to five days. This larval form is followed by the first-stage larva, and the first molt occurs in the Malpighian tubule cells at eight days. During the second larval stage, the internal organs of the worms are formed. The second molt occurs at 11 to 12 days, resulting in third stage larvae that resemble miniature adults. During the next two to three days, they lengthen, break out of the Malpighian tubules, migrate through the body to the head, and accumulate in the mouthparts of the female. These third-stage larvae are now called infective larvae. Thus, in two to three weeks microfilariae transform into infective larva. Further development can only take place when mosquitoes feed on a dog.

Infective larvae are concentrated in the proboscis, or mouthparts, of the mosquito. As the infected mosquito feeds on a dog, the infective larvae emerge from the tip of the proboscis and onto the skin of the animal. A drop of mosquito blood protects the larvae from drying prior to their entry into the host. The infective larvae penetrate the skin through the puncture wound that remains after the female mosquito withdraws her mouthparts.

Development in the Dog

After penetrating the skin, the larvae stay close to the entry site and grow very little during the next few days. The molt from third- to fourth-stage larvae occurs six to10 days after infection. Fourth-stage larvae migrate through subcutaneous tissue and muscle toward the upper abdomen and thoracic cavity. Fourth-stage larvae grow to about 1/10 inch length during the next 40 to 60 days and then molt to the fifth and final larval stage, or young adults. The young adults penetrate veins to get into the bloodstream and, eventually, after 70 to 90 days in the dog, reach the heart. For unknown reasons, the percentage of infective third-stage larvae that reach maturity varies in different breeds of dogs.

Upon reaching the heart, the young adults continue to grow. Up to now there has been no evidence of disease in the dog. It is only after adult worms mate and start to discharge tiny motile microfilariae that circulate in the blood that disease becomes apparent. Microfilariae appear in the blood about 200 days after infection.

Visible signs of heartworm disease may not appear until a full year after the dog is bitten by infected mosquitoes. In fact, the disease may be well advanced before the dog shows any symptoms. Dogs with typical heartworm disease fatigue easily, cough, and appear rough and not thriving. Blood and worms from ruptured vessels may be coughed up. Blockage of major blood vessels can cause the animal to collapse suddenly and die within a few days.

Dogs with 50 to 100 mature worms exhibit moderate to severe heartworm disease. Dogs with 10 to 25 worms that receive little exercise may never show signs of heartworm disease, and one may not be able to find microfilariae in the blood. Heartworm infection without detectable microfilaremia is called occult dirofilariasis.

Dog Heartworm Disease in Cats

Heartworm disease in cats is less frequent than in dogs. Cats are susceptible, but appear to be more resistant than dogs. The most prominent clinical signs are provided in Table 1. The average time from when the cats are infected through the bite of a mosquito until the presence of adult worms is about eight months. Outdoor cats are at the greatest risk on infection. However, a high percentage of indoor cats (as defined by their owners) have been infected. The distribution of feline heartworm infection in the United States is geographically similar to canine infection, but it occurs in fewer numbers than it does in dogs.

Differences in Heartworm Infections in Cats and Dogs

Heartworm infection in dogs is common in the United States, but infection in cats is a relatively new concern. There are important differences in several aspects of heartworm infection dog and cat owners need to know. Table 2 on the following page is modified from the American Heartworm Society's website (http://www.heartwormsociety.org) and highlights differences in all aspects of the disease in both groups of animals.

Dog Heartworm Disease in Humans

Heartworm is also an occasional parasite of humans. The parasite is usually found in the lung (pulmonary dirofilariasis), and less often in the heart. Although the worm forms a "coin lesion" in the lung, which may be confused with other diseases on x-rays, such as carcinoma, its clinical significance in man has not been fully determined. During the last 40 years about 100 cases of human pulmonary dirofilariasis have been reported from Florida.

Mosquito Vectors

Sixteen species of mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus, Ae. vexans, Ochlerotatus canadensis, Oc. cantator, Oc. excrucians, Oc. sollicitans, Oc. sticticus, Oc. stimulans, Oc. taeniorhynchus, Anopheles bradleyi, An. punctipennis, An. quadrimaculatus, Culex nigripalpus, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx. salinarius, and Psorophora ferox ) have been identified as natural hosts of D. immitis (dog heartworm) in the United States east of the Mississippi River. Among these, only 11 species are found in any abundance in Florida.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of canine heartworm infection depends on an accurate patient history, clinical signs, and use of several diagnostic procedures that may include detection of microfilariae in a blood sample, X-rays, or ultrasound.

It is much more difficult to diagnose feline heartworm infection than canine heartworm infection. Routine tests for the microfilariae are not useful in cats because the presence of heartworm offspring in the blood is temporary in cats. There are several tests used together for diagnosing heartworm in cats, including physical exam, ultrasound readings of the heart, complete blood count, blood testing, microfilaria testing, and. in some cases, necropsy.

Treatment, Prevention, and Control

Cats

There are no products approved for feline heartworm treatment in the United States. However, there are three products that have been approved as preventatives in cats: Heartgard®, Revolution®, and Interceptor®. Only a veterinarian can prescribe the appropriate product and dose. It is NOT the same for cats and dogs.

Dogs

The treatment for dogs is expensive and involves some risk to the animals. Much of the damage caused by heartworms occurs before there are any outward signs of the disease. An arsenical compound is used to kill adult heartworms in dogs; it is given as an intravenous injection, and one or two doses are given each day for two days, followed by restriction of physical activity for one to two months. As the worms die they are carried by the bloodstream to the lungs. One dog in 20 may be expected to die as a result of complications from this therapy.

Prevention is the key element in protecting a dog. If a dog is already infected, the adult heartworms and the microfilariae must be eliminated before being put on a program to prevent reinfection. Preventatives include ivermectins: Heartgard®, Heartgard Plus®, Merial, Inverhart™ Plus, Virbac; milbemycin oxime: Interceptor®, Sentinel, Novartis; and selamectin: Revolution®, Pfizer. The preventatives eliminate infective larvae before they reach the heart.

Mosquito Control

Mosquito control in residential areas where dogs and cats live can break the transmission cycle of heartworm disease. Dog owners should keep their animals out of mosquito infested areas. Living quarters should be mosquito-free. Dogs kept indoors usually show much lower incidence of infection.