Gray leaf spot disease is caused by the fungus Pyricularia grisea, also referred to as Magnaporthe grisea. The frequent warm rainy periods common in Florida create favorable conditions for this fungal disease. This fungus slows grow-in, thins established stands and can kill large areas of St. Augustinegrass turf. In Florida, St. Augustinegrass is the only warm season turfgrass affected by this important disease. However, from the mid-Atlantic states north and throughout much of the Midwest, the pathogen blights the cool season species of annual and perennial ryegrass as well as tall fescue.

Disease Symptoms and Occurrence

The most diagnostic disease symptom is an oblong leaf spot. The center of the leaf spot may have a gray felt-like growth of sporulation (formation of spores) after extended periods of warm moist conditions (Figure 1). A leaf spot may appear olive green to brown with a dark brown border when sporulation is not present (Figure 2). When the disease is severe, stands may appear thin and generally unthrifty (Figure 3). Closer inspection will reveal several leaf spots, many of which may have coalesced to turn entire blades or shoots brown. The disease generally reduces vigor of the turf and can slow grow-in of sprigged areas and the recovery of damaged St. Augustinegrass (Figure 4).

Credit: Phil Harmon

Credit: Phil Harmon

Credit: Phil Harmon

Credit: Lawrence Datnoff

Warm rainy spells from May through September commonly produce extended periods (i.e., 12 hours and greater) of leaf wetness and relative humidity greater than 95%. During these periods, turfgrass leaf blades can remain wet and air temperatures often hover between 80 and 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Environmental conditions such as these are ideal for the pathogen growth, infection, and colonization of St. Augustinegrass. If these favorable conditions persist, leaf spots can expand to blight above-ground plant tissue.

Cultivars of St. Augustinegrass differ in their susceptibilities to gray leaf spot. The disease develops more rapidly and more severely on lush leaf tissue. Lush leaf tissue is associated with rapid growth of newly-sprigged and establishing turf than on well-established stands of turfgrass. However, excessive applications of nitrogen fertilizer can result in rapid flushes of quite susceptible lush growth in mature stands. St. Augustinegrass under stress is more susceptible to infection and disease development than healthy vigorous turfgrass. Stress generally results from improper management practices that could include summer applications of the herbicide atrazine, soil compaction, nutrient imbalances or deficiencies, improper irrigation practices, other pathogens or pests, and other factors.

Disease Management

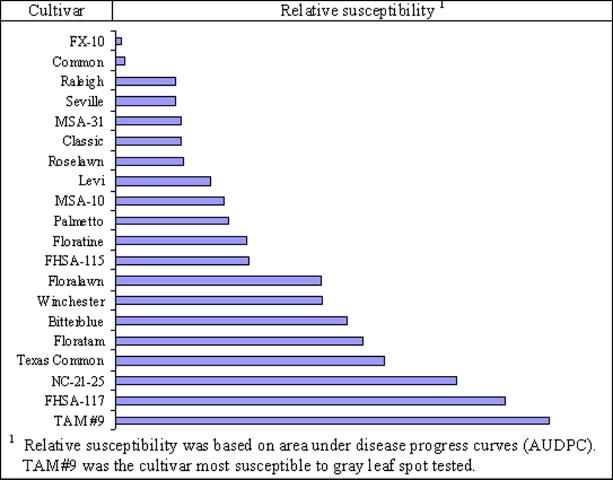

Several characteristics should be considered before new sod is purchased and installed or before a cultivar is chosen to produce sod. These characteristics include susceptibility to gray leaf spot, chinch bug resistance, and shade tolerance. Weight given to these and other factors will depend on the market, site, level of management, and expected performance of the turf. No cultivar of St. Augustinegrass currently on the market is immune to gray leaf spot, but some cultivars are less susceptible than others (Figure 5).

Credit: Russell Nagata and Lawrence Datnoff

Proper irrigation management should prevent drought-stressed turfgrass without increasing disease pressure by extending periods of leaf wetness. For example, applications made in early morning (between 2:00a.m. and 8:00a.m.) generally dry quickly on sunny days and thus limit favorable (wet) conditions for growth of the pathogen. Late afternoon or early evening irrigation should be avoided. Irrigation at these times of day allows foliage to remain wet into the evening, through the dew period, and into the next morning. Extended periods of leaf wetness favor infection and spread of the pathogen and increase the likelihood of disease (disease pressure).

Management practices that minimize stress and avoid rapid flushes of lush growth during the rainy season lessen the likelihood that severe gray leaf spot symptoms will develop. The timing of any atrazine application should be chosen carefully, since this chemistry can stress the grass especially when temperatures may climb above 85°F. Atrazine applications made before or during disease-favorable conditions increase the likelihood of severe gray leaf spot symptom development. Spot-treating trouble areas with the herbicide could also be considered. UF/IFAS recommendations on St. Augustinegrass management practices including fertilizer selection and application should be followed (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/LH010). In addition to maintaining turf vigor and health through good management practices, plant-available silicon applied just before sprigging has been shown to suppress gray leaf spot development. The publication "Silicon Effects on Resistance of St. Augustinegrass to Southern Chinch Bugs and Plant Disease" can be referenced for more information on the role of silicon application in suppressing gray leaf spot (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ss589).

Fungicide applications are important control options for St. Augustinegrass sod producers. Research at UF IFAS has shown that fungicide applications made after sprigging, during the grow-in, enhance horizontal growth and increase the rate of bare ground coverage when disease pressure is high. Fungicide products labeled for gray leaf spot management are given in the Pest Control Guide for Turfgrass Managers, available at http://turf.ufl.edu. Best results occur when fungicides are applied preventatively, according to the label, and while environmental conditions are favorable for disease development during the grow-in. Strobilurin (QoI) fungicides, such as Insignia and Heritage, are among the most effective available. Sterol inhibiting fungicides (DMI), such as Banner Maxx 1.3ME, provide some control but are most effective when tank-mixed with strobilurin products when disease pressure is high. The contact fungicide chlorothalonil is effective if applied frequently, when disease pressure is moderate to low, or as a tank-mix partner with one of the more effective systemic chemistries.

Strobilurin resistant populations of the pathogen have been identified in the Midwest. Resistance management strategies found on product labeling should be followed. Rotations of products with different modes of action and tank-mixing systemic products with contact fungicides reduce the likelihood of fungicide resistance.

Homeowner Management Options

Gray leaf spot is chronic but not typically damaging in established, well-managed home lawns. Disease symptoms may become severe if 1) the turf is stressed due to poor management or a poor (i.e., shady, damp) location or 2) unusually long periods of warm wet weather persist.

If the disease becomes a serious and persistent problem that requires attention, it is recommended that homeowners seek the services of a professional lawn care firm for management of the disease and/or lawn. Some homeowners have the equipment and knowledge required to correctly make a fungicide application on their own, including all safety equipment. If such homeowners understand the risks to both themselves and the environment, some of the fungicide chemistries listed above are available through garden centers and internet catalogs. For example, propiconazole is the active ingredient in the fungicide product Ortho Lawn Disease Control. Not all fungicides are labeled for residential lawns. Results can be erratic, because applications are difficult to make properly. Because the homeowner pesticide market and product availability can change, your local county extension agent (http://ifas.ufl.edu/extension-offices-rec-maps.shtml) or university specialist should be contacted for up-to-date product recommendations. The "Homeowner's Guide to Fungicides for Lawn and Landscape Disease Management" (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp154) can be referenced for more information concerning fungicide use in residential landscapes.

Any person who applies pesticides should always read, understand, and follow all label instructions prior to use. Specific products are listed for example only. Neither inclusion of products nor omission of similar alternative products in this publication is meant to imply any endorsement or criticism.

Related Resources

St. Augustinegrass for Florida Lawns https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/LH010

UF/IFAS Extension Plant Diagnostic Center https://plantpath.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/plant-diagnostic-center/

University of Florida Pest Control Guide for Turfgrass Managers (updated every two years) http://turf.ufl.edu

Turfgrass Disease Management https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/LH040

UF/IFAS Extension Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS) https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/

Collecting and Submitting Turf Samples for Disease Diagnosis https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/sr007