Although many homeowners enjoy wildlife in their yards, there are situations where wildlife can become a nuisance. In some circumstances, wild animals can cause extensive damage to lawns and gardens. Learning to identify which species is responsible for this damage is the first step in finding a solution to the problem. See the EDIS publication, WEC323, titled "Overview of How to Stop Damage Caused by Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard" for a complete outline of the steps to finding solutions to nuisance wildlife problems in your yard.

In this publication we provide information on the first step toward putting a stop to problems caused by nuisance wildlife: identifying the animal. Here we provide images of wildlife damage in residential settings to help you determine which species may be causing similar problems in your yard.

Animal Scat and Tracks

Although some animals are active during the day and highly visible (i.e., many birds and a few mammals), most wildlife is fairly secretive. In cases where observations of the animals themselves are challenging, you may be able to identify the animal by the droppings it leaves behind. The size, shape, and color of wildlife droppings can provide important clues. Small feces pellets the size of rice grains could be from rats, mice, chipmunks, or bats. Rounded, pea-sized pellets with rough texture are likely from rabbits. Slightly larger, smoother, oval droppings are likely from white-tailed deer, whereas smaller oval pellets could be from squirrels. Fox and coyote scat is typically 2 inches long and 1/2 inch in diameter, segmented, with tapered (pointed) ends. It usually contains hair and often bits of bone. Bobcat scat is usually about 4 inches long, segmented, and blunt at the ends. Raccoon scat has blunt ends and is uniform in thickness (1 inch in diameter). Feces from wild pigs is variable in size and shape (depending on the recent diet of the animal), but tends to be similar in shape and consistency to that of dogs. The color of feces can indicate how long ago it was left behind: fresh feces are usually moist and shiny whereas older feces tend to be dry, dull, and grayish. Take photos of the scat you find in your yard and compare your photos with photos of scat from known species of wildlife on the internet. For more details on identifying scat you can visit the Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management at https://icwdm.org/identification/feces/scat-id/.

Wildlife can also be identified from the tracks they leave behind. If the ground is hard in the area where wildlife damage is occurring and no tracks are visible, you might consider sprinkling baking flour on the ground so that new tracks will be more obvious. Again, taking photos of this animal sign can allow you to compare with photos of known animal tracks on the internet. For more details on identifying tracks you can visit the Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management at https://icwdm.org/identification/tracks/.

Soil Disturbance

Diggings are an easily observable sign that wildlife is present. In most residential settings, a few diggings are not problematic. But there may be situations where extensive soil disturbance or the location of one or more large burrows is problematic. A close look at the size, shape, and location of diggings can reveal which type of wildlife is responsible.

If you have just one or a few small holes (less than three inches in diameter), they were likely dug by chipmunks, voles, Norway rats, or snakes. Larger holes (6–12 inches in diameter) located near the base of trees, logs, or walls were likely made by red foxes, skunks, armadillos, or coyotes. The presence of tracks or trails leading in and out of the burrow, the shape of the entrance, and the odor nearby may help differentiate among these possibilities (Figure 1).

Credit: Karan A. Rawlins, https://www.forestryimages.org/

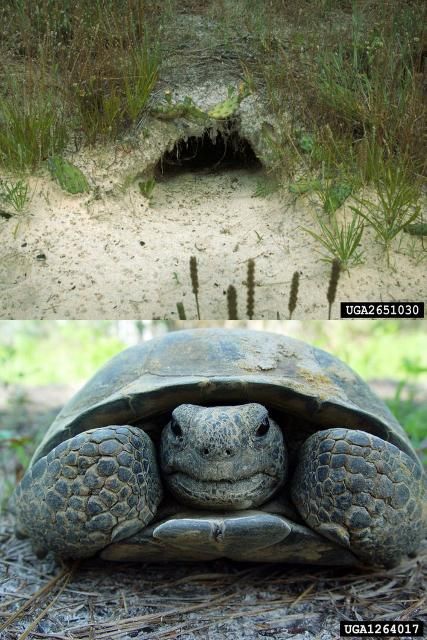

A large hole (6–12 inches in diameter) accompanied by a large mound of sandy soil is characteristic of a gopher tortoise. Gopher tortoises forage above ground but spend long periods of time underground in the large burrows they dig for shelter (Figure 2). Gopher tortoise burrow entrances are wider than they are tall to accommodate the dimensions of the tortoise shell, and a large pile of excavated sand is almost always present in front of the entrance. State law protects gopher tortoises and their burrows. Only permitted individuals are allowed to relocate them. Please do not harass, pursue, or molest them. You can report gopher tortoise locations using this app, https://myfwc.com/news/all-news/gopher-app-920/.

Credit: David Moorhead and Chuck Bargeron, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Pocket gophers (often called "sandy-mounders" or "salamanders") are secretive animals that live underground, creating tunnel systems 6–12 inches below the soil surface. They are herbivores (plant eaters), feeding on roots and fleshy plant parts. Pocket gophers excavate soil from the tunnel system and mound it into large (10 inches in diameter) asymmetrical, crescent-shaped heaps. No entrance hole is visible: a plug of soil may be seen offset from the center of the mound (Figure 3).

Credit: Arlo Kane

Moles also live in underground tunnel systems. They differ from pocket gophers in that they eat earthworms, beetles, grubs, and other insects that live in the soil. Foraging tunnels created just below the soil surface create raised ridges of soil that can create challenges for you when you're trying to mow the lawn (Figure 4). Tunnels can also kill grass if the roots become exposed to air as a result of the tunneling, and leave brown strips on the lawn. Moles can be beneficial because they feed on the larvae and adult forms of many lawn and garden pests (mole crickets, wire worms, white grubs, armyworms, etc.). But in some situations damage to lawns from extensive tunnel systems and spoil mounds (dirt excavated from tunnels) can reach nuisance levels. Soil removed by tunneling moles is deposited in small (less than 6 inches in diameter), symmetrical, volcano-shaped mounds that have an exit hole in the center.

Credit: Arlo Kane

Rooting in the soil of Florida yards is most likely caused by foraging armadillos or wild pigs. Foraging armadillos typically create many shallow holes 1–2 inches wide and up to 6 inches deep as they search for invertebrates in the upper layers of soil (Figure 5).

Credit: Eddie Powell

Wild pigs cause more extensive damage while rooting in the soil. They create deeper holes across larger areas (Figure 6). Wild pigs also create wallows in wetter areas so they can cool off by rolling in the mud.

Credit: Billy Higginbotham, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Bark Damage

Gray squirrels can damage trees by removing patches of bark from tree trunks or upper tree branches, often up in the tops of trees (Figure 7).

Credit: Randy Cyr, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Male deer can damage tree bark when they rub against stems to remove the velvet from their antlers. Bark is often removed along only one side of the stem at heights of 2–4 feet off the ground. Small-diameter trees are preferred for antler rubbing (Figure 8).

Credit: David Stephens, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Black bears cause two types of damage to trees. First, they strip the bark and then scrape the cambium from young trees with their incisors, leaving vertical scars. They create this damage while feeding on the inner bark, as well as to intentionally leave a territorial mark. Second, when they climb trees they often leave distinctive, deep grooves in the bark or cambium with their claws (Figure 9).

Credit: David Morehead, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Wild pigs damage bark when they scratch or rub on tree trunks. Wild pigs are surely responsible if mud and coarse hair remains clinging to the rubbed area (Figure 10). The height of the rub provides an indication of the size of the wild pig.

Credit: Sasa Kunovac, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Woodpeckers sometimes drill holes in the trunks of live trees. In particular, yellow-bellied sapsuckers may drill horizontal rows of deep holes ¼–½ inch in diameter in the bark of favored trees to gain access to their preferred food, tree sap and insects attracted to this sap (Figure 11).

Credit: Randy Cyr, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Vegetation Clipping

Plant parts may be consumed by a variety of wildlife including rabbits, deer, and beaver. The size of tooth marks, the bite pattern, and the size of the material consumed can be helpful in determining which species caused the damage. For example, rabbits have sharp incisors that enable them to clip vegetation cleanly, but their short stature limits this damage to low heights above the ground. In contrast, white-tailed deer lack upper incisors and therefore must rip leaves or twigs off rather than biting them, leaving behind a jagged appearance. Deer damage will occur higher up on the plant than damage caused by rabbits.

Rabbits typically clip seedlings and leaves within 15 inches of the ground, leaving a clean, angled cut on the remaining stem. Targeted stems are usually less than 1/4 inch in diameter. Tooth marks are 1/16–1/8 inches wide (Figure 12).

Credit: John Ghent, https://www.forestryimages.org/

White-tailed deer lack upper incisors, so they typically leave rough, jagged cuts when they clip pine seedlings. No obvious tooth marks are visible (Figure 13).

Credit: https://www.forestryimages.org/

Beavers typically cut shoots, saplings, or trees off at their bases, within 2 feet of the ground. Cuts are made in larger trees inward at an angle from all edges, leaving a tapered point in the middle of the stem. Individual tooth marks are 1/8–1/4 inches wide (Figure 14). Most trees damaged by beavers occur close to the waterways where beavers have created a dam. Tree species beavers prefer may be entirely eliminated in the vicinity of an active lodge.

Credit: Gerald Lenhard and James Solomon, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Vegetable Garden Raiding

Watermelons are a favorite food item of many omnivorous wildlife. Raccoons tend to dig a small hole in the side of the melon and rake out the contents with one paw (Figure 15). Coyotes bite holes and eat out the center portion of the fruit. Deer and wild pigs will paw the melon and break it open.

Credit: Donald Maynard and Gary Elmstrom

Young peanuts are favorites of deer. Because deer lack incisors, plants damaged by deer have rough, ragged breaks with shredded edges (Figure 16).

Credit: Holly Ober, UF/IFAS

Young soybeans are also susceptible to foraging by deer (Figure 17).

Credit: Daren Mueller, https://www.forestryimages.org/

Additional Sources of Information

Anonymous. "Scat and Droppings Identification Key." Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management. Available online at https://icwdm.org/identification/feces/scat-id/.

Dolbeer, R. A., N. R. Holler, and D. W. Hawthorne. 1994. Identification and assessment of wildlife damage: an overview. The Handbook: Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Eds.: S. E. Hygnstrom, R. M. Timm, and G. E. Larson. Paper 2. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmhandbook/2/

Ober, H. K. and A. Kane. 2012. Overview of How to Stop Damage Caused by Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard. WEC323. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Available at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW368

Ober, H. K. and A. Kane. 2012. How to Modify Habitat to Discourage Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard. WEC325. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Available at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW370

Ober, H. K. and A. Kane. 2012. How to Use Deterrents to Stop Damage Caused by Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard. WEC326. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Available at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW371

Ober, H. K. and A. Kane. 2012. How to Use Traps to Catch Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard. WEC327. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Available at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW372