Overview

Once the 4-H program has established a vision for how volunteers will be involved in the county, selecting volunteers is the next step. If a vision has not been developed, review “Engaging Volunteers through ISOTURES: Identifying Opportunities for Volunteer Involvement.” Program vision is a critical element in the recruitment process.

A selection and screening process is a method of strengthening the recruitment and placement of volunteers in county 4-H youth development programs. When volunteers are purposefully selected and requested to uphold high standards, there is increased credibility and value of volunteers to 4-H youth and the program. A concise policy with risk management standards will send a positive message to parents, volunteers, and other youth-serving organizations across the nation that 4-H has a focus on safety and protecting youth.

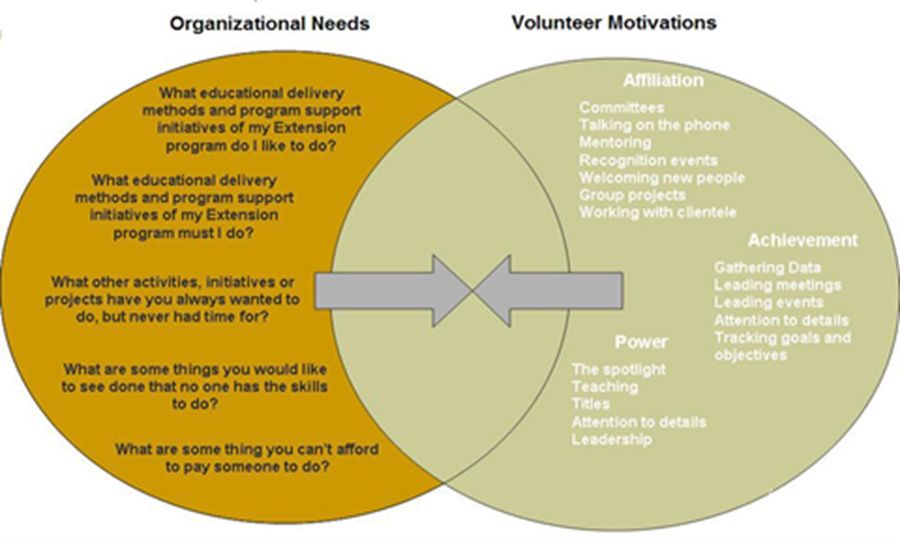

Earlier in the discussion of volunteerism, overlapping circles (Figure 1) were used to illustrate one of the roles of the 4-H agent. One circle represents the needs of the 4-H program. The other circle represents what volunteers are willing and able to do. The key to sustaining a volunteer program is the ability to match the interests, skills, and abilities of a potential volunteer with an appropriate role in 4-H. This is represented where the two circles overlap. In the volunteer life cycle, this is the Decision to Volunteer stage. The matching process is where volunteers evaluate 4-H to establish the fit between their individual needs and what 4-H has to offer. If the volunteer is not a good fit for your 4-H program, it is okay to tell them their services are not needed.

Credit: Terry, B., Godke, R., Heltemes, W., & Wiggins, L. (2010)

There are several basic steps for selecting volunteers for the 4-H program. The process begins with identifying potential volunteers, followed by applications, interviews, screening, and approving.

This fact sheet provides the basics of the selection process. Should additional questions arise or if more detail is desired, contact a UF/IFAS Extension Regional Specialized 4-H Agent or the Volunteer State Specialist at the State 4-H office.

Procedures for Selecting Volunteers in Florida 4-H

An important consideration after finding a potential volunteer is reducing risk, primarily to youth, but also to volunteers, faculty, staff, and UF/IFAS. Several policies, procedures, and regulations have been established to protect youth, volunteers, and the organization. The rules for the administration of volunteers can be found in the Rules of the University of Florida, 6C1-3.0031 Finance and Administration; Volunteers, while the volunteer policies of the University of Florida can be found in the UF HR Volunteer Policy.

Interviewing Potential Volunteers

Interviewing volunteers allows the agent to determine the best fit, get to know the potential volunteer, and evaluate where the volunteer may fit into the program. Once agents have completed the interview process and feel they are comfortable with the volunteer, they must check the volunteer’s references.

Checking References

Checking references is the next step in the volunteer selection process. A minimum of two attempts to contact two references by phone or email are required. The agent should note when the reference form was sent and whether no response was given, and they should upload any reference forms received into 4-H Online. It is important to follow all these steps because this is a state government and youth compliance requirement. Once references have been sent and the agent is still satisfied that the volunteer is appropriate for the role, it is time to proceed to volunteer screening.

Youth Protection and Volunteer Screening

To protect youth involved in our Extension programs, the University of Florida has established a volunteer screening policy. UF/IFAS applies this policy to any volunteer who serves more than 10 hours a month in a youth program or who chaperones youth.

Who Must Be Screened

All volunteers who want to work directly with youth (who are not their own children) on an ongoing basis or at an overnight event must be screened. Volunteers serving more than 10 hours a month or chaperoning minors are required to complete a level 2 screening. Those who must be screened include, but are not limited to:

- All adults who supervise youth who are not family members

- Youth volunteers (age 14–18)

- Day camp volunteers

- Resource leaders to club or county programs

- Transportation volunteers

- Master Volunteers in project areas, event management, or chaperoning

- Chaperones for out-of-county trips or other field trips

- Adults in homes that host youth involved in interstate and/or international exchange programs

- Professionals who work with Extension program youth outside of their regular job

Who Is Exempt from Volunteer Screening

Although volunteer background screening is encouraged for all volunteers, some individuals involved with Extension youth development programs are exempt from the screening process. They include:

- Adults who conduct Extension programs with only their own children

- Classroom teachers who work with youth as part of their classroom responsibilities and have been previously screened through the school system

- Event judges—one or two times per year (no chaperoning of minors)

- Donors and contributors

- Adult assistants who work in public groups with youth one time a year during a weekend and are accompanied by screened adults.

- After-school paid staff, including on-base military YDP staff, if school has previously conducted a screening process

- Advisory committee members or Foundation Board members, who do not supervise, travel, or work directly with youth

Once you have determined that volunteer screening is required, follow the process found in the 4-H Agent Guide for Managing the Approval, Denial, and Releasing of Volunteers in Florida 4-H.

Appointing the New Club Leader

Background screening is a part of the volunteer selection process. Passing a background screening does not automatically make a person a volunteer. The agent should review the entire selection process, of which screening is a part, to make the decision to appoint a person to a volunteer position. Once the decision is made, a letter of approval or denial must be sent to the applicant. Volunteers are approved on an annual basis, and a new letter of approval must be sent every year. The approval letter is then uploaded into 4-H Online. Be sure to contact the State 4-H Headquarters with any concerns related to background screening results.

Documentation and Volunteer Files

Volunteer records are required by state government for youth programming. All volunteer records must be maintained in 4-H Online. The volunteer references, national sex offender search, screening results, interview forms, and approval letter should be uploaded under the volunteer’s profile. This information is archived and used to track screening compliance.

In summary, there are a number of basic steps for selecting volunteers for the 4-H program. The process begins with identifying potential volunteers, followed by the application, interview, screening, and appointment process.

Keep in mind that the responsibilities of a 4-H agent do not end when a potential volunteer is identified.

For the protection of youth, other adults, and the 4-H program, know which volunteers must be screened and how. Finally, ensure your 4-H Online volunteer records are up to date.

References

Arnold, M. E., & Dolenc, B. (2008). Oregon 4-H volunteer study: Satisfaction, access to technology, and volunteer development needs. Corvallis, OR: 4-H Youth Development Education, Oregon State University.

Boyce, M. V. (1971). A systematic approach to leadership development. Washington D.C.; USDA, Extension Service. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 065 763)

Bussell, H., & Forbes, D. (2003). The volunteer life cycle: A marketing model for volunteering. Middlesbrough: Tees Valley. School of Business and Management, University of Teesside. Retrieved from https://research.tees.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/6373982/96938.pdf

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., & Ridge, R. (1992). Volunteers' motivations: A functional strategy for the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 2, 333–350.

Esmond, J., & Dunlop, P. (2002). Developing the volunteer motivation inventory. Perth: Lotterywest & CLAN WA Inc.

Kulp, K. (2013). Volunteer position descriptions: Tools for generating members, volunteers and leaders in Extension. Journal of Extension, 51(1), 1TOT8. Retrieved from https://archives.joe.org/joe/2013february/pdf/JOE_v51_1tt8.pdf

McCudden, J. (2002). What makes a committed volunteer? Research into the factors affecting the retention of volunteers in Home-Start. Voluntary Action, 2(2).

McCurley, S., & Lynch, R. (2011). Volunteer management (3rd ed.). Ontario: Johnstone Training and Consultation, Inc.

McEwin, M., & Jacobsen-D'Arcy, L. (2002). Developing a scale to understand and assess the underlying motivational drives of volunteers in Western Australia: Final report. Perth: Lotterywest & CLAN WA Inc.

McKee, J., & McKee, T. (2012). The new breed: Understanding and equipping the 21st century volunteer (2nd ed.). Loveland, CO: Group.

McNeely, N. N., Schmeising, R. J., King, J., & Kleon, S. (2002). Ohio 4-H youth development Extension agents’ use of volunteer screening tools. Journal of Extension, 40(4), 4FEA7. Retrieved from https://archives.joe.org/joe/2002august/a7.php

Renz, D. O., & Associates. (2010). Jossey-Bass handbook of nonprofit leadership and management, 3rd edition. Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Toelle, A., Kent, H., & Cooney, S. (2020). 4-H agent guide for managing the approval, denial, screening and releasing of volunteers in Florida 4-H. EDIS, 2021(6).

University of Florida. (2016). Regulations of the University of Florida: 3.0031 Volunteers. https://regulations.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/30031.pdf

University of Florida. (2021). Volunteer Policy. https://hr.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/volunteer-policy.pdf