Introduction

Weather monitoring is critical to decision-making in agriculture and tourism, both of which are major industries in Florida. An understanding of weather patterns supports a better understanding of the spatial distributions and temporal variations related to plants, crops, animals, and human activities, which can contribute to better preparation of farm and business management plans. The overall weather patterns (or climate) have slowly changed over time. The long-term monitoring of weather variables including temperature and precipitation (or rainfall) gives us an idea of what the current weather looks like as well as how it may change in the future. There are many different sources of weather data, and the Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN) provides accurate, real-time weather information throughout Florida (Zhang et al. 2017).

FAWN has been monitoring weather conditions at more than 40 locations across Florida. It was established to give local growers real-time weather information to support agricultural decision-making related to pesticide application, cold protection, and irrigation scheduling (Palmer 2013). FAWN has been collecting weather data for over 20 years across the state. These data have been frequently used for research and Extension as well (Matyas et al. 2009; Kisekka et al. 2010; Borisova et al. 2019).

This document gives an overview of Florida temperature and rainfall during the past 20 years based on historical FAWN data to provide information and knowledge about the temporal and spatial trends of Florida weather and the frequency and size of extreme weather events such as heavy rainfall and drought. Such knowledge can help growers identify the best types of crops for specific locations and the potential threats associated with growing those crops in a changing climate. In addition, the information can serve as a good reference for comparison and evaluation of current weather events and patterns that we observe every day, and even for scientific purposes.

This article discusses FAWN and shows the overall temporal and spatial trends in annual and monthly weather patterns. The weather patterns of the north (Santa Rosa County), east (St. Johns County), west (Hillsborough County), and south (Miami-Dade County) areas are compared to show examples of weather conditions in different geographic regions. This document also investigates the characteristics of drought and heavy rainfall in relation to hurricanes and tropical storms.

Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN)

FAWN was created in 1997 with a legislative appropriation. These funds were used to establish 11 sites that were integrated into an existing county Cooperative Extension Service network of five sites in Lake and Orange Counties for a total of 16 sites. Since then, 26 stations have been added, for a total of 42 full stations statewide. Two additional weather stations are located in Hillsborough County (the Dover station in Plant City) and Citrus County (the Lecanto station in Floral City), and they have been collecting weather data including rainfall depths and air temperature since 1998 (Dover) and 2013 (Lecanto), respectively. The monitoring periods of the stations vary, and the differences were not considered in the analysis. Continuous weather monitoring and data updates will reduce biases present in future statewide comparisons.

Each FAWN tower is equipped with sensors that measure a number of parameters, including temperature (at the depth of -10 cm in the soil and at the heights of 60 cm, 2 m, and 10 m in the air), barometric pressure, solar radiation, wind speed and direction, and rainfall amount. Several parameters are calculated as well, including dew point temperature, wet bulb temperature, and evapotranspiration. Data are collected at each FAWN site every 15 minutes, then disseminated to the public via the FAWN website, which can be accessed at https://fawn.ifas.ufl.edu. Sensor-specific information can be found at https://fawn.ifas.ufl.edu/tour/fawn_info/.

Most FAWN stations are located at UF/IFAS Research and Education Centers, but some are located on other public lands, such as the Florida Division of Forestry district offices and county Extension offices. Ideally, each site provides data that are representative of local conditions so that area growers can use the data to aid in weather-related decision-making. FAWN data are used extensively by Florida growers to support decision-making related to freeze protection, irrigation scheduling, and chemical application. Researchers also use FAWN data in research related to various crops (e.g., Pavan et al. 2009; Adapalene et al. 2017).

Averages and Extremes

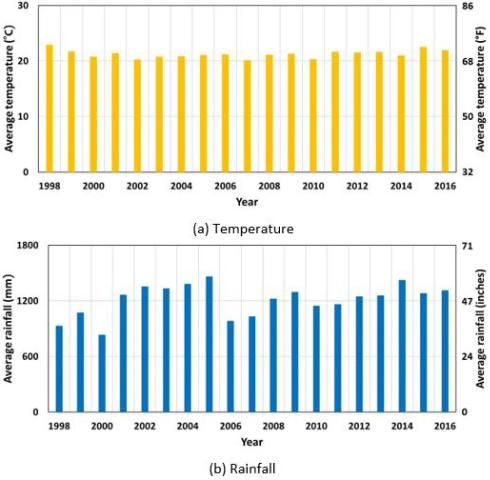

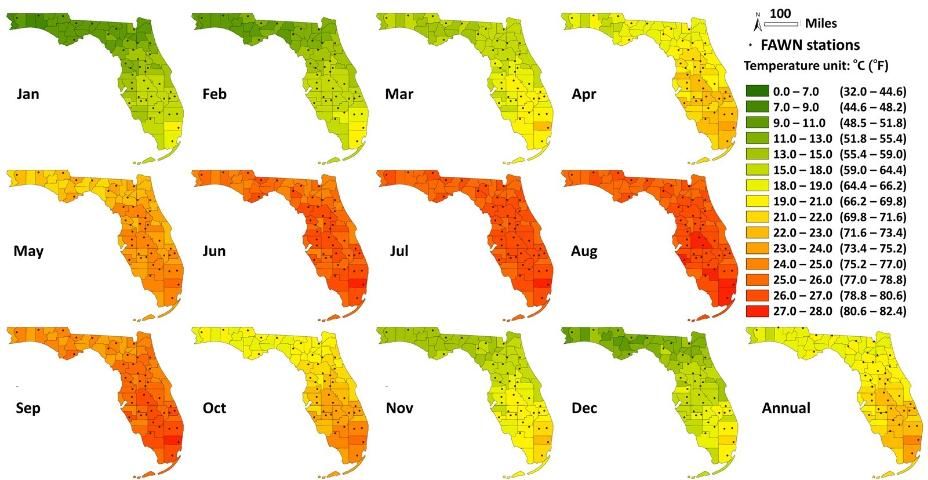

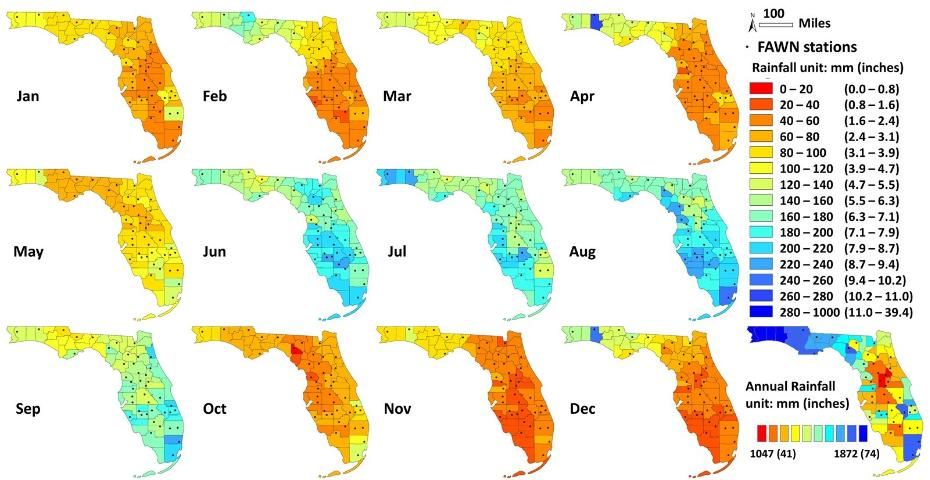

For the analysis, temperature and rainfall data from a total of 44 weather stations were obtained via the FAWN website. According to the FAWN data collected at the 44 stations, the annual average (air) temperature in Florida ranged from 20.1°C (68.2°F) to 22.9°C (73.3°F) (Figure 1a), with the warmest temperatures in Broward County, and the coldest in Santa Rosa County (Figures 2 and 3). The annual average rainfall ranged from 835.1 mm (32.9 inches) to 1,461.8 mm (57.6 inches) (Figure 1b); the wettest and driest areas were Walton and Lake Counties, respectively (Figures 2 and 4).

Credit: UF/IFAS

![Figure 2 Figure 2. Map of the Florida counties and FAWN stations. Dots show FAWN station locations, and highlighted counties show the four geographic regions of Florida (north [Santa Rosa], west [Hillsborough], east [St. Johns], and south [Miami-Dade]).](/image/AE537/13410898/16362150/16362150-2048.webp)

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

The average monthly temperature was 21.1°C (70.0°F), with Broward County being the hottest (29.6°C or 85.3°F) in July, and Santa Rosa County being the coldest (5.2°C or 41.4°F) in January (Figures 2 and 3). The average monthly rainfall was 108.0 mm (4.3 inches). Miami-Dade County was the wettest (244.0 mm or 9.6 inches) in August, and Lafayette County was the driest (15.4 mm or 0.6 inches) in October (Figures 2 and 4). Overall, the average temperature increased from the northwest (i.e., Walton and Santa Rosa Counties) to the southeast (i.e., Broward and Miami-Dade Counties). In terms of rainfall, the northern areas (i.e., Walton and Santa Rosa Counties) were wetter than the central (i.e., Polk and Osceola Counties) and southern (i.e., Palm Beach and Miami-Dade Counties) areas from November to April. The central and southern areas were wetter than the northern areas from May to October.

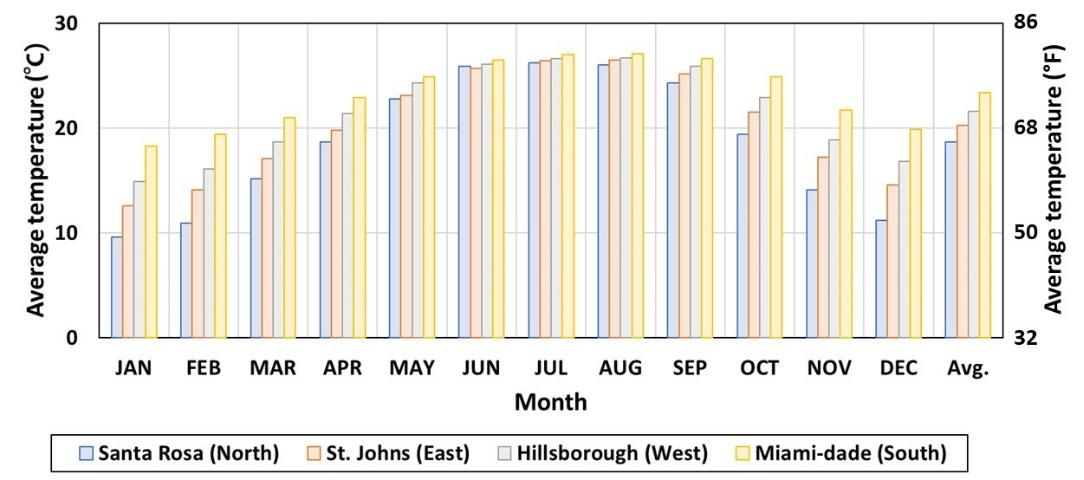

Annual Rainfall and Temperature Variations

Four counties were selected to represent the four geographic regions of Florida: Santa Rosa (north), St. Johns (east), Hillsborough (west), and Miami-Dade (south) (Figure 2). On an annual scale, the average temperature in the south was 23.0°C (73.4°F), which is higher than the temperature in the north (18.7°C or 65.7°F). In addition, the amount of rainfall (1,446.9 mm or 57.0 inches) in the south was about 270 mm (10.7 inches) greater than the rainfall depths (1,152.0 mm or 45.4 inches in the west and 1,198.2 mm or 47.2 inches in the east) observed in the west and east FAWN stations (Table 1). The differences among the average monthly temperatures in the four regions were greater in winter than in summer, and there was a clear spatial trend in the monthly temperature from the north to the south, especially in the dry seasons from November to April (Figures 3 and 5). However, the monthly temperatures of the four regions became similar to each other in the summer months from June to August. In the case of the monthly rainfall depths, a spatial trend was relatively strong from the north to the south in the dry months from November to April, compared to that of the wet months from May to October (Figures 4 and 6). The differences varied monthly and seasonally, which indicates that rainfall varies more dynamically than temperature. Overall, the average monthly rainfall amounts in all regions were greater in summer than in winter.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

Rainfall Intensity

In Florida, most of the intense rainfall events were observed from June to September (Table 2). This time period corresponds to the Atlantic hurricane season, which occurs from June 1 to November 30 (NOAA 2018). The most intense rainfall events, ones that lasted at least 15 to 30 minutes, were observed at the Kenansville station in Osceola County on July 15, 2011 (196.6 mm/hr or 7.74 inches/hr) and at the Apopka station in Orange County on October 13, 2002 (148.8 mm/hr or 5.86 inches/hr) (Table 2). The intensity of rainfall events decreased with an increase in rainfall duration. Rainfall events that lasted more than 1 hour, especially those that lasted 12–24 hours, were found to be associated with hurricanes or tropical storms (Table 2).

Intense rainfall events happened most frequently in Santa Rosa, Franklin, and Miami-Dade Counties (Jay, Carrabelle, and Homestead stations, respectively) (Table 3). On the other hand, relatively few heavy rainfall events were observed in the central areas of Florida, including Pasco, DeSoto, Indian River, and Okeechobee Counties. There was no clear spatial pattern found in the number of heavy rainfall events observed across Florida. This would suggest that intense rainfall events in Florida generally occur within highly localized storms caused by heating of the air at the surface (convectional lifting) that rises rapidly and forms cumulus or cumulonimbus clouds (dense, towering vertical clouds that can produce heavy rainfall). These intense localized events can produce heavy rainfall but may not last long; the amount of available moisture is limited, and these storms can move very quickly with the surface winds.

Drought

The FAWN data show that Florida has a relatively large amount of rainfall annually, but it often suffers from long dry periods as well. Prolonged dry seasons were observed frequently from October to May in Florida (Tables 4 and 5). The most severe drought (more than 15 consecutive dry days) was observed at the Pierson station in Volusia County in 2015 (beginning April 17 and lasting 73 consecutive days). Not far behind was one that occurred in Marion County in 2012 (beginning October 8 and lasting 63 days) (Table 4). Overall, drought events happened more frequently in Collier, Marion, Hardee, and Glades Counties than in other counties. On the other hand, rainfall events tended to be more evenly distributed in Palm Beach and Walton Counties, which resulted in fewer observable drought events (Table 5). This would suggest that central Florida tends to be drier than southeastern and northwestern Florida.

Conclusion

This document provides an overview of the current status of Florida weather in terms of trends in temperature and rainfall patterns. The historical FAWN data provided information related to extreme weather events (intense rainfall and drought) as well as overall spatial and temporal weather patterns. The FAWN data showed that Florida weather is highly variable over time and by location, and that rainfall is more variable spatiotemporally than temperature in Florida. Overall, the central areas tended to be hotter, and the southeastern areas wetter, compared to other areas. Intense rainfall events were localized, generally due to convectional lifting and tropical storms. In addition, large rainfall events that lasted longer than 1 hour tended to be associated with tropical storms, but events that were shorter than 1 hour were much more intense than ones with longer durations. This suggests a need for the development of flood mitigation plans customized for different rainfall duration scenarios. An increasing trend in the average annual temperature was found at some of the FAWN stations, but the weather monitoring period was too short to confirm a long-term trend, which suggests the need to continue such observations. Prolonged dry periods were not rare in Florida; every year, at least 24 stations on average observed drought events. These findings suggest the need to develop plans for a chronic drought to reduce its impacts on agriculture, natural resources, and tourism. FAWN data provide valuable current weather information to various stakeholders and scientist groups, but also, for this study, offer detailed insight into Florida's recent weather patterns.

References

Borisova, T., E. Conlan, E. Smith, M. Olmstead, and J. Williamson. 2019. Blueberry Frost Protection Practices in Florida and Georgia. FE1045. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe1045

Kadyampakeni, D., K. Morgan, M. Zekri, R. Ferrarezi, A. Schumann, and T. Obreza. 2017. Citrus Irrigation Management. SL446. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ss660

Kisekka, I., K. W. Migliaccio, M. D. Dukes, B. Schaffer, J. H. Crane, and K. Morgan. 2010. Evapotranspiration-Based Irrigation for Agriculture: Sources of Evapotranspiration Data for Irrigation Scheduling in Florida. AE455. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ae455

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2018. "NOAA 2018 Atlantic hurricane season outlook." Accessed on December 17, 2019. https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/outlooks/hurricane.shtml

Palmer, D. 2013. "The Big Freeze of '97 and the Birth of FAWN." UF/IFAS Blogs. Accessed on December 17, 2019. http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/ifascomm/2013/11/21/the-big-freeze-of-97-and-the-birth-of-fawn/

Pavan, W., C. W. Fraisse, L. G. Cordova, and N. A. Peres. 2009. The Strawberry Advisory System: A Web-Based Decision Support Tool for Timing Fungicide Applications in Strawberry. AE450. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ae450

Zhang, M., Y. Her, K. Migliaccio, and C. Fraisse. 2017. Florida Rainfall Data Sources and Types. AE517. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ae517

Tables

Annual average temperature and rainfall of the four counties in north, east, west, and south Florida. Temperature is given in °C (°F), and rainfall is given in mm (inches).

The number of heavy rainfall events (rainfall intensity more than 50.8 mm/hr or 2 inches/hr) observed at the FAWN stations.