Grasslands are important ecosystems worldwide. They are the base for ruminant production in many regions (Peters et al. 2013). In Florida, there are 11.2 million acres of grasslands used for beef cattle production. These operations are characterized as extensive cow-calf grazing systems without supplementation. Additionally, C4 warm-season grasses are the predominant forage, with bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum Flüggé) as the most important warm-season grass forage for livestock consumption. However, forage and livestock are not the only products obtained from grasslands. There are multiple ecosystem services, including habitat for pollinators and wildlife, nutrient cycling, greenhouse gas (GHG) regulation, and carbon (C) storage and accrual. Carbon storage refers to the total amount of C accumulated in a specific moment while accrual refers to the net accumulation or increase of C in a particular system over time, accounting for gains (e.g., C uptake through photosynthesis) and losses (e.g., decomposition, respiration, or disturbances). Carbon accrual is also known as C sequestration.

Grasslands have great potential for removing C from the atmosphere, helping contribute to the state economy while regulating GHG. Greenhouse gases are one of the main contributors to the rise in the Earth’s temperature, and human activity such as fossil fuel combustion enforces this process. Researchers, governments, and policymakers have focused on potential C storage and accrual from grasslands as an alternative mitigation strategy for climate change. Assessing the potential for C accrual and storage from the atmosphere by C4 warm-season grasses with nitrogen (N) fertilizer application and grass-legume mixtures will help determine the economic value of C under different grassland management schemes. Extensive grassland operations offer a possibility to enhance C mitigation and have great potential to add economic value to the farm (e.g., C credit programs) and support the policymaking processes from stakeholders. Information is available on enrolling in C credit programs. This Ask IFAS publication targets the education of Extension faculty and producers on understanding the C cycle in grasslands and the potential for economic valuation of C accrual in grazing lands.

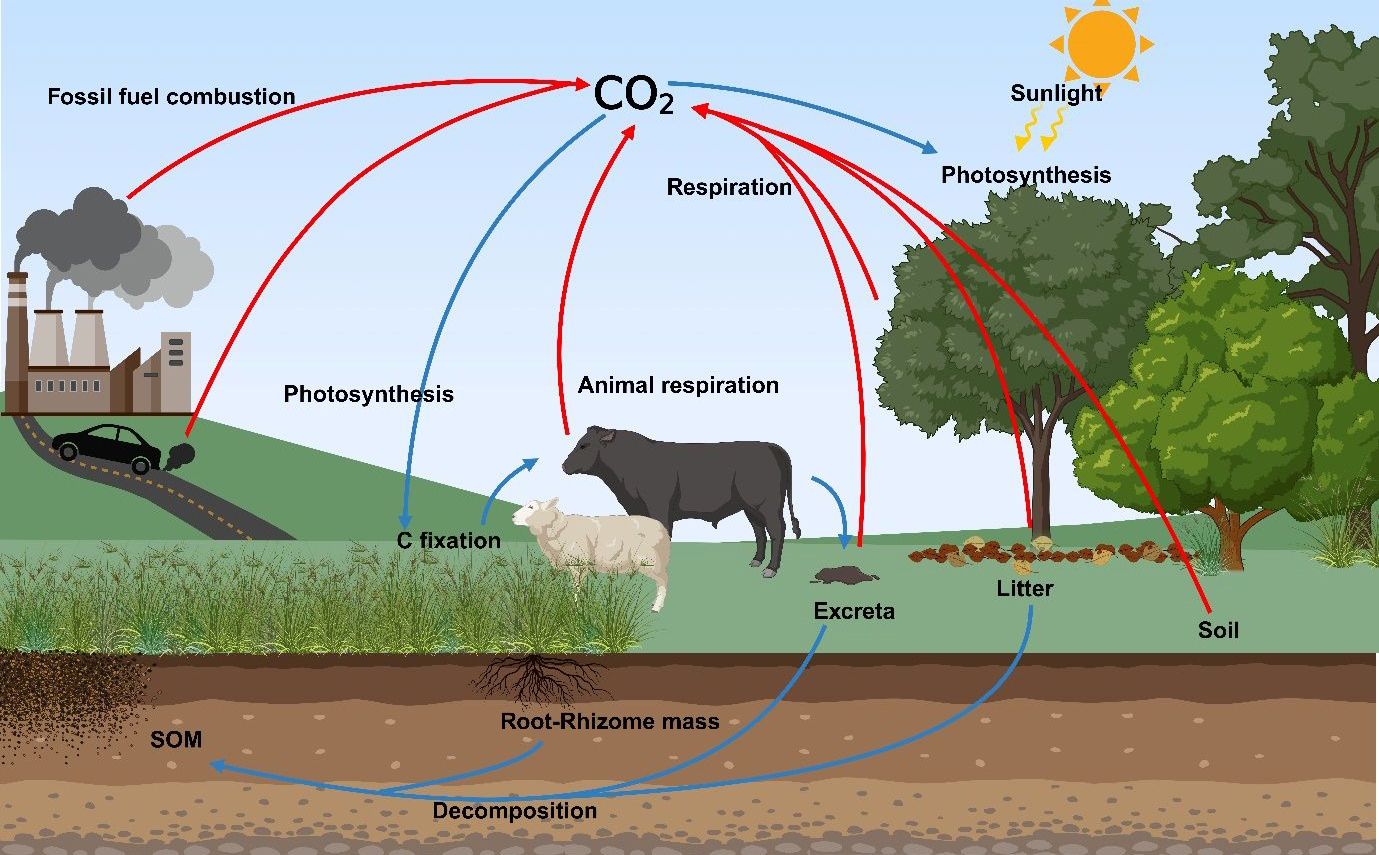

Carbon Cycle in Grasslands

The soil under grasslands stores different nutrients (Sollenberger et al. 2019), especially N and C, yet the storage of each element in the system depends on the management. Carbon is dynamic, involving movement from different pools at different rates (Figure 1). The C cycle starts when plants uptake atmospheric C to use it in the photosynthesis process so they can obtain energy to grow. The plant material and contained C can follow different patterns, and the fate of this will determine the amount and time over which the C will be stored. Plants differ in their growth, affecting aboveground and belowground biomass accumulation, litter deposition, and soil organic carbon (SOC) deposition.

Additionally, the forage ingested by livestock will be digested through ruminal fermentation, releasing methane (CH4). Enteric CH4 is the most important GHG emitted by ruminants (Boddey et al. 2020) via eructation. This is considered a loss of dietary gross energy of 5%–7% for the animals (Histrov et al. 2013). Furthermore, livestock return nutrients to the system through excreta, which is divided into urine and dung. After deposition, this material will undergo different decomposition processes and release GHG into the atmosphere. The most important GHGs released from manure are nitrous oxide (N2O), CH4, and carbon dioxide (CO2).

The new C stored in the system holds significant economic value for offsetting GHG emissions and can be traded as C credits. However, before these credits can be traded, they must satisfy certain criteria such as additionality, permanence, and leakage. The C that will be introduced into the markets has to be newly added to the system and stay there for a period. These credits serve as a currency of exchange, representing a metric ton of C stored through various management practices, and grasslands and grazing livestock are eligible practices for C markets due to the great C storage potential and emission reduction (Wade 2024).

Credit: Created in BioRender. Trumpp, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z8slxfu

Potential C Accrual from Grasslands

The potential C accrual of different grassland schemes and management has been widely studied throughout Florida (Table 1), and the different C rates can be used to evaluate the value of additions of C in contracts. For instance, in south Florida, studies on native rangelands and bahiagrass pastures demonstrated greater C accrual during the spring and summer months (Bracho and Silveira 2022), while in central Florida and the Panhandle, grass with high N fertilization tended to have greater C accrual than grass-legume mixtures.

Table 1. Carbon accrual rate of different grazing systems and land management.

Equation 1.

Therefore, one ton of C is equal to 3.67 tons of CO2. Nevertheless, C prices are normally represented per ton of CO2. In practical terms, this is the monetary value that C stored is worth, yet the payment will be on the additional C added every year by implementing new specific practices.

To illustrate this, a long-term study (2014 to present) conducted at UF/IFAS NFREC in Marianna, FL, has been quantifying the C storage in different pools. This study has different grass-only pastures and grass-legume mixtures with different N fertilization rates during cool and warm seasons. The grass-only system (Grass+N) includes cool-season grasses, RAM oat (Avena sativa L.), and Prine ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) during the cool season, and bahiagrass during the warm season; this system receives 200 lb N/acre per year. The grass-legume system (Grass+RP) is a bahiagrass-rhizoma peanut (Arachis glabrata Benth.) mixture during the warm season with no N fertilization; in the cool season, it is overseeded with a mixture of cool-season grasses and a blend of clovers, ‘Dixie’ crimson (Trifolium incarnatum L.), ‘Southern Belle’ red (Trifolium pratense L.), and ‘AU Don’ ball clover (Trifolium nigrescens Viv.), with 30 lb N/acre per year. Each experimental unit was 2.2 acres. After 10 years of evaluation, the C accrual was determined. The Grass+N system had an accrual of 1,414 lb C/acre per year and the Grass+RP system had 1,255 lb C/acre per year; thus, producers could potentially receive around 80.2 USD/acre per year and 63.9 USD/acre per year, respectively. This C payment will depend on the market volatility, including the speed of the C credit generation and the selling process.

Results suggest that Florida's beef cattle industries can gain increased economic benefits, not only from beef production but also through C accrual and storage by participating in C markets, where C can be traded globally as C credits for GHG emissions offsets.

Note that grasslands are not the only land cover managed by farmers in Florida. In fact, the change of practices allows producers to get into C markets and brings the additional C to the system, which will be paid off. These contrasting land uses, each with a different C accrual rate, contribute to the overall farm C accrual. Table 1 lists several examples that can be used to estimate the value of a C contract in the southeastern United States.

In summary, our findings of the potential and economic value of C accrued from grasslands allow land managers to link their situation to current and future regional and national policy decisions on C management strategies, C market, and C credits. The overall monetary quantification of C accrual that grasslands provide will allow farmers, cattle producers, Extension agents, and policymakers to make better decisions in different land management practices in similar climatic and soil conditions. This represents an opportunity for farmers who are interested in enrolling in C markets based on the amount of C accrued and the performance of their grasslands.

Enrolling in the Market

Ask IFAS has different publications related to C markets, which can be found at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topics/carbon-markets. Ask IFAS publication FE1154, “An Introduction to Carbon Credit Markets and Their Potential for Florida Agricultural Producers,” includes specific information on how the market works and how to enroll (Boufous et al. 2024). To enroll in a C market program, the farm must incorporate a new practice that will add to the market new C that has been accrued as an additional benefit. Different strategies that help mitigate the effects of global warming are qualified to be added to C markets such as practices related to reducing GHG emissions or avoiding GHG emissions (e.g., improvement of fertilizer use efficiency, energy conservation). These include but are not limited to sustainable production practices such as tree establishment, crop rotation, cover crops, no-till planting, and grazing livestock.

Among all pools storing C, the soil is where more C can be stored because the soil is better protected from degradation and decomposition processes associated with biotic and abiotic factors. Thus, as an example of the process involved in engaging in the C market, we will use SOC.

Contracts of C markets vary depending on each specific situation, yet SOC contracts are long-term agreements because changes in the soil happen slowly and take many years to show (Her et al. 2023). Additionally, the payment depends on the agreement of each party at the beginning of the contract stipulation, which might include who will oversee the sampling and verification process. Note that farmers face initial costs when adopting a new sustainable practice that might include changes in machinery, soil planting management, and the inclusion of cover crops, among others.

After enrollment in a C program, a third-party company will be involved in estimating and verifying the SOC (Boufous et al. 2024). In southeast Florida, most recommendations for soil sampling are from 0 to 6 inches; however, the depth of estimation will depend on previous parameters and recommendations made by the company. Deeper soil samples enhance the overall soil C estimation. This step may be disruptive because it requires researchers and workers to be at the farm for soil sampling. The estimated SOC will set a baseline, allowing the farm owner, in conjunction with researchers and the company, to compare usual with more innovative land management practices. In the second stage, companies need to report and certify the C credits by a third party. This is because C markets pay for performance and not for practice; the companies need to ensure that C was accrued. Finally, C accrual is verified, and the company will issue a unique serial number. This serial number helps in putting the C credits in the market and avoiding double counting. The time frames of the C credit generation and the final purchase are not specific because they follow market demand.

The final step involves putting the C credits on the market. The current C market is global, and different organizations impose different rules. Gold Standard, Verra (ACR), Climate Action Reserve, California Air Resources Board, and Science-Based Targets are multinational companies that have developed policies. Even though all farms can get into this market, these companies prefer large-scale farms because the cost associated with the process is high, and the total land area and potential C accrual will determine the revenue for each party. Carbon credits are traded by C platforms such as Indigo, Bayer Carbon Program, Corteva, and Nutrient ESMC. For more information about the C market and ways to trade in it, visit https://www.climateactionreserve.org/how/carbon-market-directory/.

In Florida, potential C credit programs are the Sequestering Carbon and Protecting Florida Land Program, CIBO Impact, Agoro Carbon Alliance, and Ecosystem Services Market Consortium (ESMC).

Final Considerations and Conclusions

Grasslands not only facilitate forage and livestock production but also provide several other ecosystem services. The C accrual information and stock data from this publication provide a quantitative basis of grassland C services and their economic value, improving farm decision-making as well as enhancing the supply of ecosystem services. Economic valuation of C accrual by grasslands will stimulate beef cattle operations since they face growing concerns about global warming potential. Strategies that enhance ecosystem services will promote these industries by adding economic value. Florida grasslands represent a partial solution for removing atmospheric CO2 while contributing to the farm economy. Nevertheless, the C market is evolving, and more work must be done in the U.S., especially in Florida, to develop a reliable verification process for grazing systems.

References

Allen, L. H., S. L. Albrecht, K. J. Boote, J. M. G. Thomas, Y. C. Newman, and K. W. Skirvin. 2006. “Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Accumulation in Plots of Rhizoma Perennial Peanut and Bahiagrass Grown in Elevated Carbon Dioxide and Temperature.” Journal of Environmental Quality 35(4): 1405–1412. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2005.0156

Boddey, R. M., D. R. Casagrande, B. G. C. Homem, and B. J. R. Alves. 2020. “Forage Legumes in Grass Pastures in Tropical Brazil and Likely Impacts on Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Review.” Grass and Forage Science 75(4): 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/gfs.12498

Boufous, S., T. Wade, S. Chakravarty, M. Andreu, J. H. Bhadha, Y. G. Her, and Z. Yu. 2024. “An Introduction to Carbon Credit Markets and Their Potential for Florida Agricultural Producers: FE1154, 9/2024.” EDIS 2024(5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fe1154-2024

Bracho, R., M. L. Silveira, R. Boughton, J. M. D. Sanchez, M. M. Kohmann, C. B. Brandani, and G. Celis. 2021. “Carbon Dynamics and Soil Greenhouse Fluxes in a Florida's Native Rangeland Before and After Fire.” Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 311: 108682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2021.108682

Bracho, R., G. Starr, H. L. Gholz, T. A. Martin, W. P. Cropper, and H. W. Loescher. 2012. “Controls on Carbon Dynamics by Ecosystem Structure and Climate for Southeastern U.S. Slash Pine Plantations.” Ecological Monographs 82: 101–128. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-0587.1

Chamberlain, S. D., P. M. Groffman, E. H. Boughton, N. Gomez‐Casanovas, E. H. DeLucia, C. J. Bernacchi, and J. P. Sparks. 2017. “The Impact of Water Management Practices on Subtropical Pasture Methane Emissions and Ecosystem Service Payments.” Ecological Applications 27(4): 1199–1209. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1514

da Silva, L. S., L. E. Sollenberger, M. Kimberly Mullenix, M. M. Kohmann, J. C. B. Dubeux, and M. L. Silveira. 2022. “Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Nitrogen‐Fertilized Grass and Legume–Grass Forage Systems.” Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 122(1): 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-021-10188-9

Dubeux, J. C. B, L. Garcia, L. M. D. Queiroz, E. R. S. Santos, K. T. Oduor, and I. L. Bretas. 2023. “Carbon Footprint of Beef Cattle Systems in the Southeast United States.” Carbon Footprints 2–8. https://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cf.2022.16

Gomez‐Casanovas, N., N. J. DeLucia, C. J. Bernacchi, E. H. Boughton, J. P. Sparks, S. D. Chamberlain, and E. H. DeLucia. 2018. “Grazing alters net ecosystem C fluxes and the global warming potential of a subtropical pasture.” Ecological Applications 28(2): 557–572. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1670

Her, Y. G., T. Wade, S. Boufous, J. Bhadha, and M. Andreu. 2023. “Florida’s Agricultural Carbon Economy as Climate Action: The Potential Role of Farmers and Ranchers: AE573/AE573, 5/2022.” EDIS 2022(3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-AE573-2022

Herrero, M., B. Henderson, P. Havlík, P. K. Thornton, R. T. Conant, P. Smith, S. Wirsenius, A. N. Hristov, P. Gerber, M. Gill, K. Butterbach-Bahl, H. Valin, T. Garnett, and E. Stehfest. 2016. “Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Potentials in the Livestock Sector.” Nature Climate Change 6(5): 452–461. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2925

Hristov, A. N., J. Oh, J. L. Firkins, J. Dijkstra, E. Kebreab, G. Waghorn, H. P. S. Makkar, A. T. Adesogan, W. Yang, C. Lee, P. J. Gerber, B. Henderson, and J. M. Tricarico. 2013. “Special Topics — Mitigation of Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Animal Operations: I. A Review of Enteric Methane Mitigation Options.” Journal of Animal Science 91: 5045–5069. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2013-6583

Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases (IWG). 2021. “Technical Support Document: Social Cost of Carbon, Methane, and Nitrous Oxide: Interim Estimates under Executive Order 13990.” United States Government.

Jensen, E. S., M. B. Peoples, R. M. Boddey, P. M. Gresshoff, H. N. Henrik, B. J. R. Alves, and M. J. Morrison. 2012. “Legumes for Mitigation of Climate Change and the Provision of Feedstock for Biofuels and Biorefineries. A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 32(2): 329–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-011-0056-7

Knight, B. 2024. “Beyond Cover Crops and Tillage: How Can We Really Calculate Farm Carbon Emissions?” Agri-Pulse Webinar. https://www.agri-pulse.com/media/videos/play/1050

Peters, M., M. Herrero, M. Fisher, K.-H. Erb, I. Rao, G. V. Subbarao, A. Castro, J. Arango, J. Chará, E. Murgueitio, R. van der Hoek, P. Läderach, G. Hyman, J. Tapasco, B. Strassburg, B. K. Paul, A. Rincón, R. Schultze-Kraft, S. Fonte, and T. Searchinger. 2013. “Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Eco-efficiency of Tropical Forage-based Systems to Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” Tropical Grasslands — Forrajes Tropicales 1(2): 156–167. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc

Poeplau, C., and A. Don. 2015. “Carbon Sequestration in Agricultural Soils via Cultivation of Cover Crops — A Meta-analysis.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 200: 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.10.024

Samuelson, L. J., T. A. Stokes, J. R. Butnor, K. H. Johnsen, C. A. Gonzales-Benecke, T. A. Martin, W. P. Cropper Jr., P. H. Anderson, M. R. Ramirez, and J. C. Lewis. 2017. “Ecosystem Carbon Density and Allocation across a Chronosequence of Longleaf Pine Forests.” Ecological Applications 27(1): 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1439

Silveira, M. L., P. J. Rodrigues da Cruz, J. M. B. Vendramini, E. Boughton, R. Bracho, and A. da Silva Cardoso. 2024. “Opportunities to Increase Soil Carbon Sequestration in Grazing Lands in the Southeastern United States.” Grassland Research 3(1): 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/glr2.12074

Silveira, M. L., S. Xu, J. Adewopo, A. J. Franzluebbers, and G. Buonadio. 2014. “Grazing Land Intensification Effects on Soil C Dynamics in Aggregate Size Fractions of a Spodosol.” Geoderma 230–231: 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.04.012

Sollenberger, L. E., M. M. Kohmann, J. C. B. Dubeux, and M. L. Silveira. 2019. “Grassland management affects delivery of regulating and supporting ecosystem services.” Crop Science 59(2): 441–459. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2018.09.0594

Vogel, J. G., R. Bracho, M. Akers, R. Amateis, A. Bacon, H. E. Burkhart, C. A. Gonzales-Benecke, S. Grunwald, E. J. Jokela, M. B. Kane, M. A. Laviner, D. Markewitz, T. A. Martin, C. Meek, C. W. Ross, R. E. Will, and T. R. Fox. 2022. “Regional Assessment of Carbon Pool Response to Intensive Silvicultural Practices in Loblolly Pine Plantations.” Forests 13(1): 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010036

Wade, T. 2024. “An Introduction to Carbon Programs and Markets.” UF/IFAS Southwest Florida Research and Education Center. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wE6kcNBHSGA&t=9s

Xu, S., M. L. Silveira, K. S. Inglett, L. E. Sollenberger, and S. Gerber. 2016. “Effect of Land-use Conversion on Ecosystem C Stock and Distribution in Subtropical Grazing Lands.” Plant Soil 399: 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2690-3