Introduction: Parasites in Small Ruminants

Credit: Kevin Korus, UF/IFAS Extension

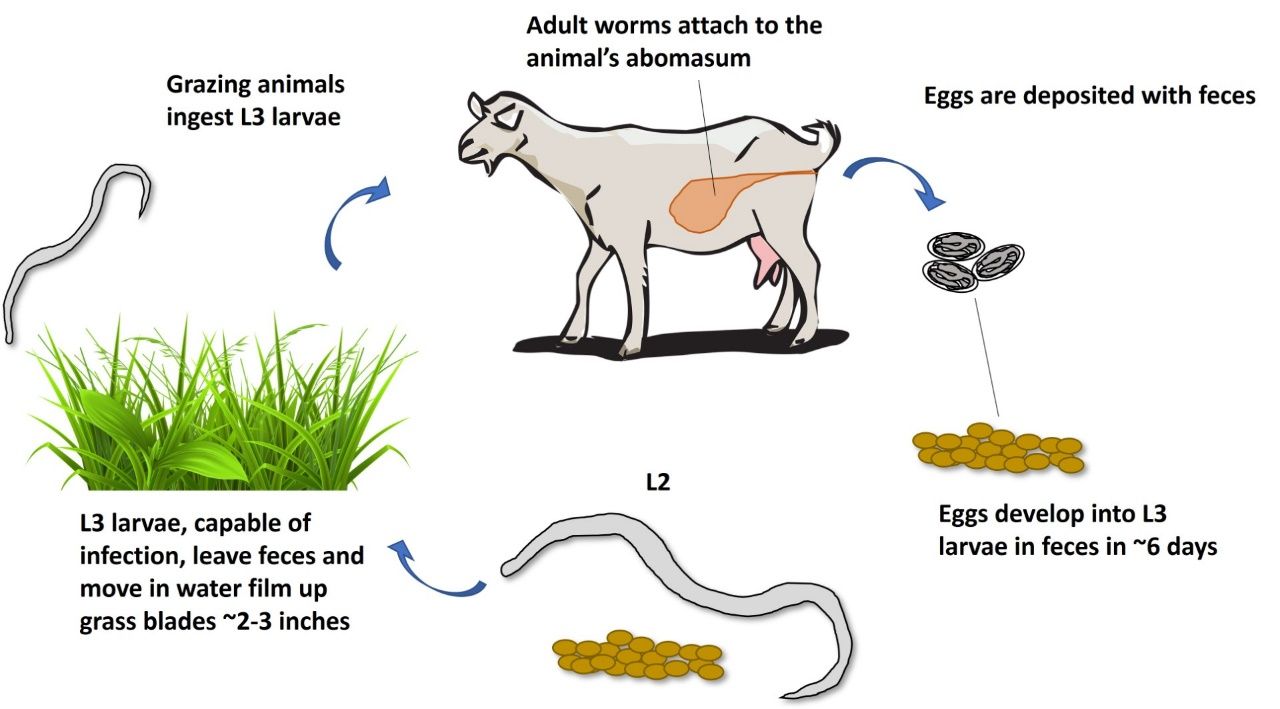

Internal parasites are a primary concern among small ruminant producers. Small ruminants in the Southeastern United States are prone to parasite infection, and most animals will likely become infected at some point in their life cycle. Among other gastrointestinal parasites, the barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus) is the most common and economically important internal parasite of small ruminants (Figure 1). Infections from this organism pose a risk to producers and affect overall production if not managed correctly.

Understanding signs of parasite infection and the several strategies available to effectively monitor and manage parasites is essential for successful management of small ruminant operations.

Symptoms of Parasite Infection

Parasites can cause various symptoms in sheep and goats that often resemble signs of other problems or diseases. These symptoms can vary greatly between individual animals and should not be solely relied upon for a diagnosis. It is crucial for small ruminant producers to understand and identify symptoms of illness in their animals, while also using other strategies such as FAMACHA© scoring, fecal egg counts, and veterinarian expertise to diagnose parasitic infection.

The most important worms to the small ruminant producer and the topic of this publication are gastrointestinal parasites. A variety of families of internal parasites can reveal infection of an animal through a multitude of symptoms, and identifying these symptoms may narrow down the potential causes for illness. Infection by the barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus) is the primary cause of anemia in small ruminants in many countries (Flay 2022) and can occasionally be accompanied by generalized edema in acute cases, as well as progressive weight loss. Trichostrongylus and Strongyloides, such as the black scour worm (Trichostrongylus colubriformis) and the intestinal threadworm (Strongyloides papillosus), are associated with anorexia, persistent diarrhea, weight loss, and submandibular edema, also known as bottle jaw. Symptoms of Trichuris (whipworm) infection include congestion, diarrhea, and general unthriftiness.

General symptoms of most gastrointestinal parasite infections include:

- Anemia

- Weight loss

- Diarrhea

- Anorexia (drop in feed intake)

- Submandibular edema (bottle jaw)

- Generalized edema

- Rough hair coat

- Weakness

- Depression

Identifying Animals for Testing

Individually testing all members of a herd or flock is tedious and requires additional labor and other operation resources. Therefore, it is not feasible for many small ruminant producers. While observable symptoms cannot be the sole determinant in parasite infection diagnosis, they can help producers to identify animals that should be further evaluated. Look for animals in the herd that are displaying potential symptoms of parasites. If possible, isolate them from the general population to conduct further testing. These tests include fecal egg counts and FAMACHA© scoring to determine parasite loads and treat accordingly.

Identify animals that show signs of weight loss, diarrhea, general edema, and a general poor and unthrifty condition for further testing. Submandibular edema, commonly known as “bottle jaw,” is the presence of a soft swelling under the jaw that indicates parasite infection; producers should deworm any animals with this symptom immediately (Figure 2).

Pay special attention to particularly vulnerable individuals, including young animals that have not yet fully developed immunity, as well as lactating females. Carefully selecting individual animals to be tested and treated will save the producer time and money, and will slow the development of parasitic resistance to anthelmintic drugs in the herd or flock.

Credit: Susan Schoenian, sheep & goat specialist (retired), University of Maryland Extension

Why FAMACHA© Training Is Important

The FAMACHA© scoring system allows small ruminant producers to decide which animal they should treat and which animal they should selectively deworm in their flock or herd. The FAMACHA© scoring system was developed in South Africa and consists of a method to identify sheep and goats heavily infected with the barber pole worm, which feeds on the host’s blood and causes anemia. Being able to use FAMACHA© scoring is important because it allows the producer to be selective in the deworming process. Selective treatment minimizes the development of drug resistance in gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) parasites. Producers can also use FAMACHA© scoring to aid in selective breeding decisions by identifying those animals that are most susceptible to barber pole worms.

FAMACHA© scoring is only applicable if the barber pole worm is the main gastrointestinal nematode parasite causing clinical disease. Eye diseases, environmental irritants, or systemic diseases can sometimes cause redness from the ocular membranes. However, these are typically uncommon. A FAMACHA© score is not the only reason that you should deworm your herd or flock. Other gastrointestinal nematode parasite signs include diarrhea, bottle jaw, poor body condition score, dull hair coat, or heat intolerance. FAMACHA© scoring is a great technique to use in any operation, whether big or small.

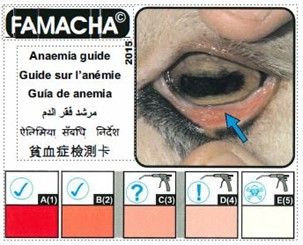

How to Perform a FAMACHA© Test

The FAMACHA© system uses a color chart that shows 1 to 5 subjective scores based on the color of the ocular conjunctival mucous membranes of small ruminants. This membrane turns from red to pale white as anemia is increased. The membrane color is compared with the FAMACHA© card chart, and the animal is scored accordingly (Figure 3). The higher the number, the paler the membrane is, which indicates increased anemia and a greater possibility of heavy parasitism. The color-coding system is 92% accurate in assessing anemia levels in small ruminants.

Credit: FAMACHA©

The use of FAMACHA© requires formal training and certification. The certificate allows producers to obtain the FAMACHA© identification card and perform the test on their small ruminants. You can obtain a FAMACHA© card by going through a formal training through UF/IFAS Extension, a university online FAMACHA© certification process, or through a person who is authorized to provide the formal training.

How to Use the FAMACHA© Card

- Cover the animal’s eye by rolling the upper eyelid down over the eyeball.

- Carefully push down on the eyeball.

- Carefully pull down the lower eyelid.

- The mucous membranes will pop into view. Hold the score card near the eye and match the color of the pinkest portion of the mucous membranes to the FAMACHA© card (Figure 4).

- Repeat the process for the other eye.

Credit: Lizzie Whitehead, UF/IFAS Extension

How to Interpret the FAMACHA© Scoring Results

For Animals in FAMACHA© Categories 1 and 2

Do not deworm animals in these categories unless there is other evidence of parasitic infection, such as poor body condition score, loss of appetite, presence of diarrhea, and dull hair coat.

For Animals in FAMACHA© Category 3

Consider deworming animals in this category if:

- More than 10% of the flock/herd have scores of 4 or 5;

- They are lambs and kids;

- They are pregnant or lactating ewes/does;

- The animals have poor body condition score;

- The animals have additional health problems; or

- The animals have a compromised immune system.

For Animals in FAMACHA© Categories 4 and 5

Always deworm animals in these categories.

How Often to Perform the FAMACHA© Test

The effectiveness of the FAMACHA© scoring system depends upon regular use. An overall parasite control strategy must consider the life cycle of the parasite. Usually, it is recommended that FAMACHA© scoring is performed every 2–3 weeks depending on the season. In addition, efforts should be made to reduce egg shedding on pastures and to reduce the incidence of animals grazing in contaminated pastures.

During high worm transmission periods (e.g., warm and humid weather), make plans to move animals to a safe pasture, increase nutritional supplementation, and perform FAMACHA© scoring on animals every 7–10 days. Lambs and kids have smaller blood volumes, and heavy infections can cause apparently healthy animals to die in as little as 10–14 days.

If more than 10% of the flock/herd score in categories 4 and 5, it is important to recheck weekly, and, regardless of the season, treat all category 3 animals and change pastures if possible.

Maintaining the FAMACHA© Card

Store the card in a dark place when not in use because the card colors will fade over time. It is recommended that you replace the card after 12–24 months of use, depending on storage conditions. If possible, keep a spare card in a place protected from light and compare the colors with the card in use.

Final Considerations for FAMACHA© Scoring

The FAMACHA© scoring ultimately helps to decrease the use of dewormers by identifying potentially infected animals and allowing producers to selectively treat their livestock. Keep accurate and thorough records that can help with the identification of “problem animals” who are susceptible to parasites and require frequent deworming. Additionally, it is always recommended to check animals for the presence of a soft swelling under the jaw (i.e., bottle jaw). All animals with bottle jaw must be treated, whether they appear anemic or not.

The FAMACHA© scoring system is only one component of a good management program for the barber pole worm and cannot be used on its own. A good, integrated management control program must be used, which includes regular observations for symptoms, fecal egg counts, and working with a veterinarian.

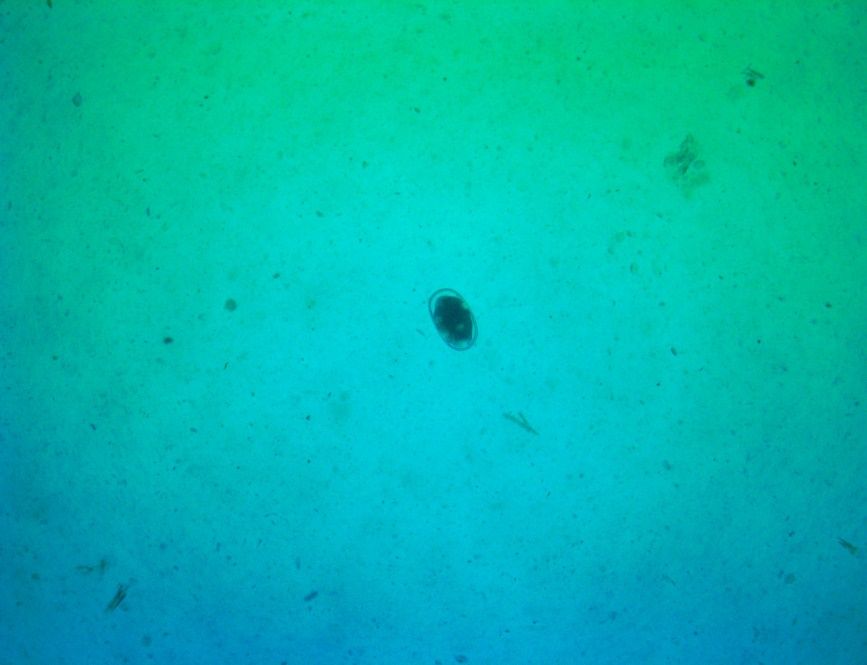

Fecal Egg Counts: How to Collect, Process, and Analyze Samples

Performing a FAMACHA© test will tell you whether an animal is anemic, which typically means that it is nutrient deficient. However, it does not give any clues to the cause of deficiency. Further tests need to be performed to confirm if parasite infection is the cause of a nutrient deficiency and thus anemia. The process to evaluate the number of parasites in an infected animal involves evaluation of their fecal material. Parasite eggs can be separated from fecal debris using a flotation fluid (saline solution). Because of the buoyant nature of parasite eggs, they float to the surface and can be viewed at the top of a specialized microscope slide. Fecal egg counts can be used to identify and measure the number of eggs per gram of manure. Samples must be viewed through a compound microscope with magnification from 100X to 400X.

The following is a summary of the Modified McMaster fecal egg counting procedure developed by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program in collaboration with the University of Rhode Island and Virginia Tech.

Sample Collection

For accurate assessment of the levels of parasitic worms in each animal, fresh fecal samples need to be collected and analyzed for each individual animal. Samples should be taken directly from the animal and not collected from the ground. Steps for collecting a proper rectal fecal sample can be found on page 2 of the McMaster fecal egg counting procedure (https://web.uri.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/241/McMaster-Test_Final3.pdf). After samples have been collected, make sure that they are labeled and stored in the refrigerator. If many samples need to be collected at one time, have a cooler with ice to store samples until they can be put into the refrigerator. Alternatively, samples can be collected from animals immediately after depositing; however, feces that sit on the ground can become contaminated by many other organisms. Samples are more readily collected from animals that have been at rest. If necessary, pen the animals for a while before collecting. Never collect rectal samples from young animals. Do not force your fingers if they do not fit.

Sample Processing

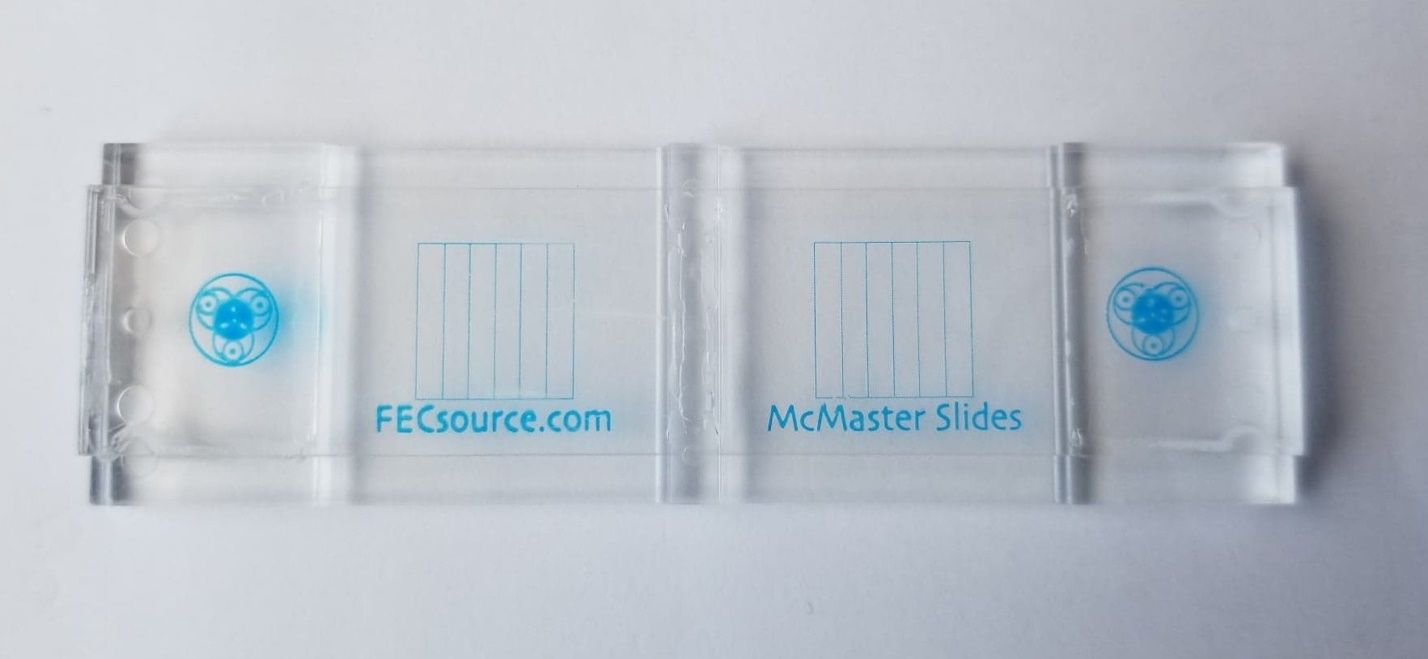

Samples are macerated, mixed with flotation solution, and strained through mesh fabric such as cheesecloth. This liquid solution is then loaded into specialized McMaster slides for viewing with a compound microscope. It is important to load the two chambers of the McMaster slide without allowing air bubbles. Air bubbles reduce the amount of solution in each well and alter the true egg count. To reduce the likelihood of air bubbles, use a transfer pipette to load the wells from the top by holding the slide at a 45° angle.

Sample Analysis

The saline solution added to the sample allows parasite eggs to float to the surface. Eggs can be viewed with a compound microscope and counted. Count only the eggs inside of the blue lined wells (Figure 5).

Credit: Kevin Korus, UF/IFAS Extension

Focus the microscope on the blue lines to ensure that you are viewing the top plane of the microscope slide. Count the eggs in both chambers, add them together, and then multiply the sum by 50. This gives the number of eggs per gram of fecal material. For reference on the amounts of fecal sample and the normal range of fecal egg counts per gram, and pictures for parasite egg identification (Figure 6), consult the following: https://web.uri.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/241/McMaster-Test_Final3.pdf. Treatment thresholds have been established based on parasite populations. Consult your veterinarian for decisions on whether to treat your animals.

Credit: Kevin Korus, UF/IFAS Extension

Managing Anthelmintic Resistance

Anthelmintic (dewormer) resistance is characterized by a decrease in the sensitivity of a parasite population to antiparasitic drugs, meaning the drug loses the ability to effectively kill internal parasites. Years of overuse and misuse of available dewormers have led to the development of widespread resistance in the small ruminant industry, which has resulted in major changes to the recommended use of dewormers in small ruminants. Before, researchers and drug manufacturers recommended deworming the entire herd or flock on a schedule (Escobar 2018). Now, the widely accepted practice is to administer dewormers only when needed to the individuals that need treatment. Drug resistance is inevitable; however, producers can manage and slow the development of resistance on their farms by adhering to proper management practices.

Selective treatment, as mentioned earlier, should be used to identify animals that need treatment so that dewormer can be administered to only those animals that need it. Animals displaying symptoms of a potential parasite infection should be confirmed to have worms by fecal egg count and FAMACHA© score.

Proper dosing should be practiced to ensure animals are not underdosed, which majorly contributes to drug resistance. Animal weights should be used to inform and adjust dewormer dosing. If livestock scales are not available to the producer, a weight tape should be used at minimum to estimate body weight for at least the largest animal. Use the weight tape to measure from the point of the shoulder to the pin bone, and around the heart girth. Pull tape snugly around heart girth, then calculate the weight by using the following formula: (girth x girth x length) / 300 = weight within 2 lb.

Appropriate equipment and correct procedures are crucial to proper drug administration and limiting the development of resistance. Animals should be drenched over the tongue toward the back of the mouth with a drenching syringe that has been cleaned and maintained.

Feed restriction for 24 hours prior to dosing can increase the effectiveness of some drugs. This slows digestion and may leave the drug in contact with the parasite for a longer period. Consult the drug label as well as your veterinarian to ensure this practice is a good fit for your operation.

Repeat dosing has also been shown to decrease efficacy of dewormers. Be sure to follow drug labels and instructions from a veterinarian to ensure the safety of livestock.

Combination dosing can be done to increase the effectiveness of parasite treatments and take advantage of the additive effect of dewormer drugs. Combination dosing involves using two drugs at the same time separately, not in a single dose. Combination dosing should be done under the guidance of your veterinarian.

Finally, one of the best methods to slow anthelmintic resistance is simply limiting the use of dewormers in an operation as much as possible. Providing animals with improved nutrition and meeting changing nutrient requirements as they fluctuate throughout the animals’ life cycles will reduce mortality rates associated with parasite infection. Good pasture management practices, such as maintaining low stocking rates and rotational grazing, can help manage parasites. Pastures should not be grazed shorter than a 3-inch stubble height. Parasites must travel up grass blades to be ingested by livestock, so preventing grass from getting too short will reduce the number of parasites ingested. Producers can also genetically select for parasite immunity in their herds and flocks. Studies have shown that the ability to regulate worms is under genetic control in small ruminants (Tsukahara et al. 2021). By culling animals with chronically high parasite loads and purchasing sires and replacements that are low in parasite numbers, a small ruminant producer can reduce the amount of dewormer used from the previous year, and thus slow the development of resistance.

Conclusions

The management of gastrointestinal parasites is one of the primary concerns of small ruminant producers. It is best practice for producers to understand and monitor for signs of illness in their herd or flock and use methods such as FAMACHA© scoring and fecal egg counts to identify parasite infection. FAMACHA© scores aid in the differentiation of the severity of anemia in small ruminants, a critical indicator of barber pole worm infection. FAMACHA© scoring is an important management practice that allows producers to selectively treat potentially infected livestock. Fecal egg counts can be used by producers to identify the type and severity of parasite infection. Through the adoption of recommended management practices, such as monitoring, identifying, and treating instances of gastrointestinal parasite infection in small ruminants, producers can reduce herd or flock mortality due to infection and contribute to slowing the development of anthelmintic resistance in the industry.

References

Escobar, E. 2018. “Myths and Misconceptions about Small Ruminant Gastrointestinal Parasites Control.” Journal of Animal Science 96: 201–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/sky404.437

Flay, K. J., F. I. Hill, and D. H. Muguiro. 2022. “A Review: Haemonchus contortus Infection in Pasture-Based Sheep Production Systems, with a Focus on the Pathogenesis of Anaemia and Changes in Haematological Parameters.” Animals (2076-2615) 12 (10): 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12101238

Tsukahara, Y., T. A. Gipson, S. P. Hart, L. Dawson, Z. Wang, R. Puchala, T. Sahlu, and A. L. Goetsch. 2021. “Genetic Selection for Resistance to Gastrointestinal Parasitism in Meat Goats and Hair Sheep through a Performance Test with Artificial Infection of Haemonchus contortus.” Animals (2076-2615) 11 (7): 1902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071902

Zajac, A., K. Petersson, and H. Burdett. 2014. "Why and How to Do FAMACHA© Scoring." Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program Project. https://web.uri.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/241/FAMACHA-Scoring_Final2.pdf