Abstract

Florida’s fish and fisheries are vital to the state’s economy, but often people want or need to know just how economically important they are. However, “economic importance” means different things depending on what economic approaches are used. Understanding these differences is necessary for discussing the economic importance of fisheries and how they might be affected by management actions or environmental changes. This publication is the second part in a three-part series that summarizes different types of economic metrics and how they are often used in a fisheries context. The first publication in the series, Understanding Metrics for Communicating the Economic Importance of Florida’s Fisheries Part I: An Overview, provides an overview and explains how economic measures can be subdivided into two main groups: 1) those that quantify market activity, and 2) those that measure economic value. This second publication focuses on how regional economic methods are used to quantify market activity. It provides a discussion of the most relevant terms and analyses, as well as a brief discussion of how one might proceed with a regional economic analysis that would provide these types of measures for Florida’s fisheries (and related aspects like aquaculture or coastal resources). This information should help readers, especially management agencies and Extension agents, as well as the interested public, better understand the metrics associated with quantifying market activity.

Words and phrases shown in bold text appear in the glossary section near the end of this publication.

Introduction

Fisheries and aquaculture provide or support many goods, services, and opportunities for humans that interact with them. In Florida, examples can include recreational fishing (people fishing from shore or from their own boats), for-hire fishing (people fishing with guides or charters), commercial fishing (catching fish to sell), and aquaculture activities (raising fish to sell). These aquatic resources are often assumed to be economically important, but sometimes we want to measure how important they are. Measuring the economic importance of a certain fishery or aquaculture sector can help state or local government make decisions about management and investment. Economic analyses can also help us understand how changes to these fisheries (such as from fishing regulations or environmental disturbances), might translate to changes in the economy. Changes in the economy can include both changes in economic activity (e.g., revenue and jobs), or economic value (overall benefits to society). This publication focuses on market activity and will:

- organize, define, and describe commonly used terms and metrics associated with quantifying market activity;

- describe how these metrics can be used in decision-making contexts; and

- describe potential data sources and/or methods for estimating these metrics.

This information can help management agencies, outreach personnel, and the interested public understand terms commonly used to quantify market activity associated with fisheries and related aquatic resources in Florida.

Overview of Document Structure

Quantifying market activity is complicated to explain for two reasons. First, quantifying market activity is different from, but often confused with, measuring economic value. Second, the concept of market activity includes multiple “aspects”, each with its own metrics and/or levels. This means a lot of terms with specific definitions are used to explain quantifying market. We organized this document to first describe the difference between market activity and economic value. Then, we describe three aspects of market activity: types of market activity analyses, market activity levels, and economic metrics. After this we describe some of the data necessary for undertaking regional economic analyses of market activity. All the specific terms are defined in-text and are also summarized in a glossary.

Measures of Market Activity versus Measures of Economic Value

As discussed in Understanding Metrics for Communicating the Economic Importance of Florida’s Fisheries Part I: An Overview, there are two main types of measures of economic importance: measures of market activity and measures of economic value. In non-scientific terms, measures of market activity focus on spending (people buying goods or services), and measures of economic value focus on quantifying benefits to society (an increase in peoples’ utility). Detailed information on measures of economic value will be included in “Understanding Metrics for Communicating the Economic Importance of Florida’s Fisheries: Part III—Measures of Economic Value,” in progress. Confusingly, sales revenues are included in both measures of market activity and measures of economic value. For example, the sale of $100 of commercially caught grouper is used when quantifying the market activity associated with commercial fishing and when calculating economic value (consumer and producer surplus) of people buying the grouper. This overlap is visualized in greater detail in Figure 1 of Part I of this series. For this publication, we will be focusing solely on market activity, which is described in greater detail in Figure 1 of this publication, the components of which will be described in the following paragraphs.

Measures of market activity are, in general, summary terms of activity associated with sales and purchases between industries, governments, and consumers in exchange for goods and services. Market activity can be quantified as a producer’s sales revenue or a consumer’s direct expenditures, as well as how money from these sales cycles through a region’s economy. Measures of market activity can help answer questions like “How many jobs does a fishery support?” or “How would a change in the number of recreational fishing trips affect sales revenues or jobs in a region?.”

Types of Economic Analyses to Measure Market Activity

The tool used to assess market activity within an industry or associated with an activity is regional economic analysis. There are several types of models used for regional economic analysis, including input-output (IO) models, econometric IO models, computable general equilibrium models, etc. This publication focuses solely on IO models because they are the simplest, most common, and least data-intensive method of conducting a regional economic analysis. Input-output analysis uses information about sales and purchases among industries and institutions within a regional economy to estimate the total economic activity associated with a particular activity, event, or policy. Several user-friendly software packages such as IO-Snap or IMPLAN support these types of analyses. These software packages and others like them can be used to perform economic contribution analyses or economic impact analyses. Contribution and impact analyses have distinct definitions and interpretations (Watson et al. 2007). Economic contribution analyses quantify market activity associated with an existing industry or set of ongoing activities. Economic impact analyses measure changes in market activity resulting from a change within a given industry, or as a result of a new activity or a change in policy. Simply put, economic impact analysis is used when new things happen, or a change occurs, and contribution analysis is appropriate for “steady state” sectors. For example, one would use an economic contribution analysis to measure market activity associated with the red drum fishery of Charlotte County, Florida, in a year when nothing remarkable happened. An economic impact analysis would be used when something remarkable happened (like a red tide or fishery regulation change) to assess how the sector’s economy was affected. To summarize: market activity is assessed with regional economic analyses, the most common regional economic analyses are IO-based and performed with a specific software package like IO-Snap or IMPLAN, and these programs can run either an economic contribution analysis (an analysis of something ongoing, like an unchanged oyster fishery) or economic impact analysis (analysis of a change, like the restoration of an oyster fishery).

Levels of Economic Activity

There are four different levels of economic activity measures that can be estimated with an IO model: direct effects, indirect effects, induced effects, and total effects. Direct effects measure the sales or expenditures of a good or service of interest within a region (e.g., sales revenue from commercially caught fish). These direct sales or expenditures are associated with indirect effects and induced effects, which are described as “additional rounds of activity or spending” because they describe necessary activity to support direct effects. Indirect effects describe activity within the economic region of interest associated with input goods and services (e.g., ice or bait used to catch and preserve fish). Induced effects refer to activity that occurs as a result of expenditures of the households employed in directly affected industries and indirectly affected industries (e.g., money that fishers and bait suppliers spend on housing, food, entertainment, etc.). Induced effects are only estimated within a model that considers households to be an economic sector that supplies labor to other sectors in exchange for income, which is then used to purchase goods and services. For more detailed information on how households can be modeled and the concept of induced effects, see Miller and Blair (2022). As long as they are quantifying the same metric, direct, indirect, and induced effects can be summed to estimate total effects, or total economic activity. It is critical to understand that these levels are “backwardly linked.” This means that indirect and induced effects describe the spending that had to happen before or to enable the direct sale. Indirect and induced do not represent forward links—like additional sales that happen because of or after the direct sale (e.g., revenue from restaurants who bought fish from a wholesaler who purchased fish from a commercial fisher). To summarize: direct effects lead to additional rounds of spending or activity. Within each additional round of spending, there are indirect and induced effects. For example, a recreational fisher purchases bait from a local shop so they can go fishing. That bait shop purchases inputs and pays their employees to provide their service to the recreational fisher (selling the bait). This activity leads to another round of spending, which then continues until the remaining value is negligible. It is important to note that through each round of spending, there are leakages, which refer to the money that leaves the region or leaves the cycle via imports, savings, etc. The value of these leakages is not included when summing rounds of indirect or induced effects. Example 1 illustrates these levels of spending.

Example 1 – Florida’s shellfish aquaculture industry

Suppose decision-makers are interested in the economic role that the existing shellfish aquaculture industry plays within the Big Bend region of Florida. Here is how an economist might think about this:

- Analysis type: Contribution analysis using an IO model—because this is an existing aquaculture industry rather than a new one.

- Direct effects: Shellfish farmers’ revenue from selling clams, oysters, or another shellfish product.

- Indirect effects: Sales revenues in other backwardly linked industries associated with the purchase of ice, fuel, aquaculture supplies, etc. by shellfish farmers as well as all additional rounds of purchases of input goods and services. Basically, this is what the farmers needed to buy or pay in order to make their sales.

- Induced effects: Sales revenues associated with spending by employees whose wages come from the shellfish aquaculture industry and the indirectly supported industries (e.g., stores supplying ice, fuel, aquaculture supplies, etc.). This is the spending that is necessary for the purchases/payments the farmers make to produce and sell their oysters, clams, or other shellfish.

Direct, indirect, and induced effects are estimated through the quantification and use of economic multipliers. These multipliers are ratios that describe how the outputs of a particular industry are supported by purchases made throughout the entire economy within a particular region. For example, a 1.25 output multiplier for the commercial fishing industry sector means that an additional $25 of output throughout the economy is necessary for every $100 in commercial fishing industry output. Multipliers are the basis for IO analysis. Larger multipliers mean a greater degree of interdependency between industry sectors within a region’s economy at a certain point in time. Inaccurate estimates of economic multipliers can lead to misrepresented relationships between industries in a region, which can lead to incorrect estimates of the economic activity associated with a particular industry or change. Multipliers are not typically calculated “by hand,” even by economists, but instead are derived through the data and methods packages in IO software such as IMPLAN. For example, IMPLAN includes a comprehensive database spanning over 500 industry sectors from which industry-, region-, and year-specific multipliers are derived under different modeling specifications. The economist must determine how reliable they believe the multipliers are for the specific question they are addressing. For example, applying a state-level multiplier for agriculture to a state-level analysis of a specific type of agriculture (e.g., fruit and vegetable production) that is dominant in the state is likely be more reliable than applying that same multiplier to a less common type of agriculture (shellfish aquaculture) in a specified region of the state, for instance, Levy County.

Metrics That Measure Economic Activity

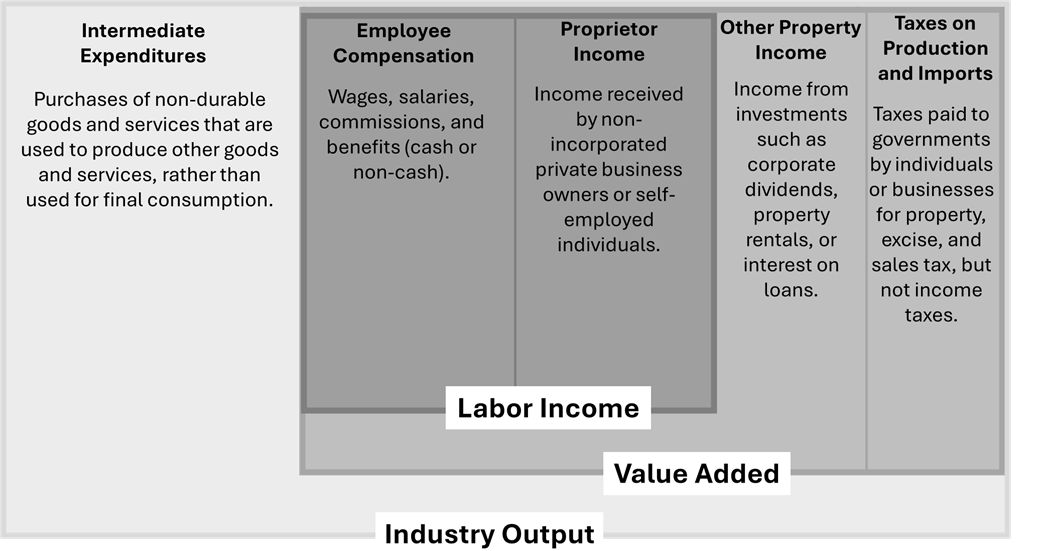

There are several different metrics by which market activity can be measured. These typically include metrics such as output, value added, labor income, and employment. These metrics each tell us something different about market activity, in the same way that salinity, dissolved oxygen, temperature, etc., all tell biologists different things about water quality. Output (also often referred to as industry output) is the most commonly used metric in a fisheries context. It describes the total value of sales or sales revenues associated with a particular industry or activity. Output includes the value of intermediate inputs (i.e., input goods and services) as well as value added. Value added is a measure of wealth created by an economy and can be thought of as the value that an industry adds to the intermediate inputs that are used during the production process. This added value includes the value of labor (e.g., the wages, salaries, etc. paid to employees and proprietors) as well as taxes paid and profits. Labor income is the sum of employee wages, salaries, and benefits and proprietor income (including payments received by self-employed individuals and unincorporated business owners). Finally, the metric employment is a measure of the number of jobs and can be measured in jobs (total number of both full-time and part-time employees) or in full-time equivalents (FTEs).

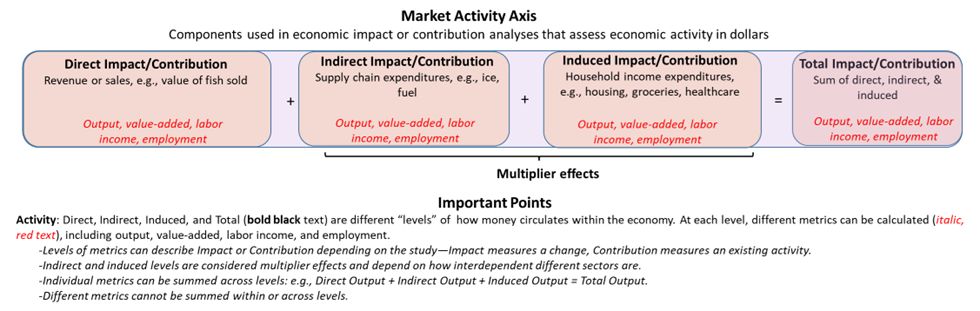

Figure 1 describes how the major market activity terms are connected. The market activity axis in Figure 1 shows that additional activity occurs within the local economy beyond the direct market activity (revenues/expenditures). Essentially, a sale cannot happen without other related purchases taking place (i.e., purchase of supplies to catch fish, equipment to hold fish, labor to operate equipment, and housing, etc.). This axis comprises different levels of market activity: direct, indirect, and induced, as well as the sum of the three, or the total impact/contribution. Note that multiplier effects are only used when calculating Indirect and Induced market activity levels, not Direct. Each of these market activity levels can be estimated within economic impact and economic contribution analyses. Also, each can be measured in terms of several different economic metrics, such as output, value added, labor income, employment, etc. It is important to understand that market activity calculations for a specific sector, like a commercial fishery, work “backwards” from the initial ex-vessel sale of fish. This means that expenditures that had to happen for the fish to be sold by the fishers go into the overall contribution or impact, but sales happening after that initial sale (e.g., wholesale fish market selling to a grocery store, which sells to a consumer) are not calculated in commercial fishery impact or contribution. (These sales would be captured if the sector was, for example, grocery store fish sales, instead of commercial fishing.)

As seen in Figure 2, some of these metrics are components of each other, so it is not always appropriate to sum different measures of economic activity. However, individual metrics can be summed across activity levels (e.g., summing direct, indirect, and induced labor income effects to produce total labor income effects).

Example 1 can be extended to examine economic metrics and multipliers as in Example 2:

Example 2 – Florida’s shellfish aquaculture industry

Building upon the concepts previously provided in Example 1.1, we can add economic metrics to quantify market activity of Florida’s shellfish aquaculture industry. This example uses values published in Botta et al. (2021), focusing on one economic metric: output.

- Analysis type: Economic contribution through IO analysis (region: Florida; period: 2018; software: IMPLAN)

- Results:

These results indicate that there were $16.0 million in sales revenues or direct output effects associated with Florida’s shellfish aquaculture industry. To produce this amount or value of shellfish, shellfish producers purchased input goods and services from other industries, and those industries made purchases of input goods and services and so on throughout multiple rounds of spending. As a result of these rounds of spending, an additional $4.6 million in sales revenues were supported via the purchase of goods and services originating in Florida (indirect effects). Also, the employees earning wages in the shellfish aquaculture industry and the indirectly supported industries spend a portion of those wages within the Florida economy, supporting an additional $8.8 million in sales revenues throughout the economy (induced effects). The sum of direct, indirect, and induced output indicates that the Florida shellfish aquaculture industry supported $29.4 million in output throughout Florida’s economy, including multiplier effects.

Additionally, these results allow for the estimation of an imputed output multiplier, which is the ratio of total output to direct output. Other multipliers like output multipliers are in the calculation of indirect, induced, and total outputs, but imputed multipliers are used to after total output is calculated, almost like a “check” or “back calculation” of the multipliers. Imputed multipliers are calculated as:

- Imputed output multiplier: 29,394 ÷ 16,049 = 1.83

The imputed output multiplier of 1.83 implies that for every $100,000 in output (sales revenues) within the Florida shellfish aquaculture sector (presumably produced to satisfy final demand), an additional $83,000 in output is supported throughout Florida’s economy.

Useful Data and Tools

A common question about approaches for examining market activity (impacts or contributions) within fisheries, aquaculture, and related fields is: what types of data are needed and how detailed must they be? In other words, how fine-scale can the question be while still getting a useful answer? The short answer to this is that impact and contribution studies can be as fine scale as the data and information that are available. Good analysis of market activity will require three types of information. The first type of information needed is how much of the good or service is bought or sold in a certain region at a certain time (e.g., total sales of fish from aquaculture or commercial fishing in Collier or St. Johns County, or the total number of trips taken for recreational fishing in Lee County). The second type of information needed is costs that go into making those sales or purchases (e.g., itemized costs of producing fish for commercial fishing or aquaculture, or the itemized expenditures necessary to take a recreational fishing trip). The final type of information needed is precisely how industry sectors in a specific economic region are related to each other. This last is the information that is used to “link” sectors and is provided by IO software packages, such as IMPLAN. This industry sector information is usually generalized from broader sectors (e.g., aquaculture is one component of a larger industry sector Other animal production excluding cattle and poultry production), so the analyst must decide if the industry sector is reasonably detailed and representative for the activity they are intending to measure. The level of detail and reliability of a market activity analysis depends on how detailed and reliable the data from these three sources of information are.

Depending on the analysis and industries in question, IO software packages are often good sources of reliable economic data. IMPLAN is one of the most popular market activity analysis software products, containing economic data derived from multiple federal sources including the United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), and Bureau of Labor Statistics, usually available on a county, state, or national scale. Within IMPLAN, there are 546 unique industry sectors, each with its own estimates of trade flows and inter-industry dependencies, depending on the regional scale. In some cases, the analyst may need to adjust these trade flows and inter-industry relationships to more accurately reflect an industry’s behavior. Analysts may need to gather additional data on sales revenues or expenditures from additional sources, and then use the new data to modify the existing economic data in IMPLAN. For example, aquaculture production is a component of the larger industry sector Other animal production excluding cattle and poultry production. The default trade flows for this industry sector depend on the economic region but can contain trade flows that are representative of other animal production industries that are not similar to aquaculture production (i.e., land-based hog farming vs. nearshore shellfish farming). In this case, it is imperative to use additional data sources to modify the existing relationships for the Other animal production excluding cattle and poultry production sector to reflect aquaculture production’s unique relationships. This information can be derived from sales revenue data and the use of enterprise budgets, which detail the costs and inputs required to maintain production.

Sales revenue data are often published by state or federal statistical agencies, such as the BEA, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), or the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). Data for activities or events at smaller regional scales (e.g., county, city, or a specific coastline) or for very specialized industry sectors (e.g., oyster aquaculture, coral reef restoration) can also be gathered via survey techniques. Levels of employment, income, or value added associated with direct market activity can also be derived from additional sources, such as government reports. The Census of Aquaculture, published by the USDA, is one example of a study that reports on direct market activity. For example, the 2018 USDA Census of Aquaculture reports a total of $71.7 million in sales revenue for all Florida aquaculture products (USDA NASS 2019). This sales revenue value could be used as the basis for a regional economic analysis that might be conducted involving this industry.

Example 3– Information needed for assessing the market activity of aquaculture

- Sales information. If sales information is not specific to the species being grown, it will be difficult to assess the market activity associated with that species. If there is species-specific information, but not county- or region-specific information, it would be possible to assess the market activity associated with the species at different scales, but these estimates would not reflect characteristics of a particular county or multi-county region. For industries that do not change their behavior much across space, estimates will likely still be reliable. For industries that behave differently in different locations (e.g., aquaculturists that use different technologies or gear to grow the same species in different locations), data that are not specific to the region will make results less reliable.

- Information about the expenditure patterns (or production functions). Analysts need detailed information about the expenditures that take place to produce an aquaculture product. This information needs to be considered representative of the industry sector of interest. For example, if the cost information mostly comes from surveys of offshore finfish aquaculture or ornamental aquaculture, it will not be appropriate for use to analyze oyster aquaculture.

- Information about the economic region. Analysts need to have a general idea about how different sectors in an economic region interact. National level data are available from the BEA and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Input-output softwares, such as IMPLAN, often estimate and provide these economic data for regions that are smaller than the nation, such as states and counties. For industries like aquaculture that are categorized within a larger sector within the existing models, secondary data sources and information on expenditures and sales must be used to modify the characterizations of industry-to-industry purchases. This will allow for a more accurate and reliable representation of how aquaculture interacts with surrounding industries in the economic region.

Example 4 – Information needed for assessing market activity of recreational fishing

- The number of fishing trips taken. This information can be at any specified level of detail, depending on data availability. For example, if analysts were interested in the market activity associated with recreational fishing in a given county during 2022, they would need to know how many trips were taken in that county for the entire year. If they wanted to know the market activity associated with for-hire, red drum trips in Walton County, the analysts would need to have trusted estimates of those specific trips only.

- Information about expenditures associated with fishing trips. Some of this information is provided by NOAA at the state-specific level by trip type. NOAA lists private vessel, for-hire, and shore-based trips. Estimates for Florida are provided for both the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. For analysts to use the NOAA information when calculating market activity of for-hire red drum trips in Walton County, they would have to assume that the average Gulf Coast trip expenditures on for-hire recreational fishing trips are reflective of for-hire red drum trips. This might be the case for a species like red drum but might not be the case for a specialized type of recreational fishing trip such as shore-based fishing for sharks, where the costs per trip are almost certainly much greater than the average because the inputs (bait and gear) are larger and more expensive.

- Information about the economic region. In the case of recreational fishing, this information is less relevant than in the case of aquaculture. Here, there is no recreational fishing industry sector, so the analyst must use information from the previous two points to define and enter a final demand pattern associated with recreational fishing that will be used to “drive the model.”

Summary

In general, quantifying market activity involves measuring spending within an industry or sector (like commercial fishing or aquaculture) in a certain region during a certain period. The two most common regional economic analyses used to estimate broader measures of market activity are economic contribution analyses (which quantify the market activity of an existing, relatively unchanged sector), and economic impact analyses (which analyze the effects of a change in a sector). Both types of analyses can be completed using an IO model and software packages such as IO-Snap or IMPLAN. These models account for direct effects, indirect effects, induced effects, and their sum, total effects by working backwards to account for economic activity that had to happen for the sales of an industry (e.g., all the spending and payments necessary for commercial fishers to obtain and sell fish). The different levels (direct, indirect, induced) are assessed using economic multipliers, which describe how dependent one industry/sector is on others within a region. At each level, market activity can be measured with different metrics, including output, value added, labor income, and employment. Some of these metrics (e.g., output) are broader and encompass others (e.g., value added), so the different measures cannot always be summed together. The basic steps for completing an economic activity analysis are:

- Identify the activity, the economic region, and the period of interest.

Example: the oyster aquaculture industry of Franklin and Wakulla counties in 2022.

2. Determine if the appropriate analysis method is an economic impact analysis (a change) or an economic contribution analysis (steady state).

Example: is the interest in quantifying activity in the current aquaculture industry (economic contributions) or is the interest in a change associated with a new regulation or environmental event, such as a hurricane or harmful algal bloom (economic impacts)?

3. Collect or estimate the direct value of market activity and decide what economic sector this activity takes place in.

Example: Collect data on the revenues of shellfish aquaculture operations. Shellfish aquaculture is a component of the agriculture industry in most definitions of economic sectors in the United States and can be used to appropriately modify the existing agriculture industry to better represent the aquaculture industry.

4. In models where households are considered a productive economic sector, estimate the indirect, induced, and total effects using multipliers derived from IO analysis within a regional economic modeling software like IO-Snap or IMPLAN.

Market activity analyses will be subject to a number of limitations. A good resource for the limitations is available from IMPLAN, with some of the most important assumptions and limitations including:

- There are no supply constraints. This means that the estimated level of economic activity associated with measured impacts (e.g., output, jobs, etc.) is assumed to be possible. For example, if an economic impact assessment suggests a doubling of commercial fishing activity will be necessary to satisfy some new level of demand, the model will not check whether regulations, environmental conditions, management plans, or fish populations can support such growth in this sector.

- Only backward linkages are considered, meaning that what happens after the direct effects is not included. If the sector of interest is commercial fishing, then activity “further along” the supply chain that is associated with activities such as processing and packaging seafood products or wholesale/retail trade of seafood products will not be captured unless the user explicitly estimates and includes the forward linkages.

- Prices are constant. Market activity models will not account for any change in price due to, for example, an increase in production.

Quantifying market activity is important because it measures (narrowly or broadly) revenues and jobs associated with a particular industry or activity. However, it is critical to remember that measures of market activity do not describe economic value or benefits to society (Part 3 of this series, “Understanding Metrics for Communicating the Importance of Florida’s Fisheries: Part III: Measuring Economic Value,” in progress, will include more information on economic benefits to society in the context of fisheries). This means that measures of market activity might be useful to report and can and should inform decision making, but they should not be the only economic measures considered when deciding if something is “good” for the economy or society. For example, a properly conducted regional economic analysis can describe the economic impacts associated with restoring a large oyster reef (e.g., Botta et al. 2022), but even though such a restoration might bring millions of dollars to the regional economy, it does not mean that the restoration project was a net benefit to society, or that it is more or less beneficial than any other alternative use of the funds. Market activity is best used in combination with measures of economic value to help decision makers and the public understand broad measures of economic activity associated with an industry or activity as well as additional benefits to society brought about by that industry or activity.

Glossary

Direct effects: Also referred to as direct market activity. The value of sales or the money that is spent on a good or service of interest within an economic region.

Economic activity levels: Term used in this context to describe the different levels of market activity that are derived through regional economic modeling. These include direct, indirect, induced, and total effects.

Economic contribution analysis: A method of regional economic modeling that measures the total market activity within an existing industry or associated with a preexisting set of activities.

Economic impact analysis: A method of regional economic modeling that measures the changes in market activity and flow of dollars resulting from a change within a given industry, or as a result of a new activity or new policy.

Economic multipliers: Multipliers are derived from an IO model and express the degree of interdependency between sectors in a region’s economy. Multipliers are measures of the total economic activity that occurs as a result of direct economic activity. Multipliers are industry specific and are derived from data on the economic structure as measured at a certain point in time and in a certain place; therefore, they can vary considerably across sectors, regions, and time.

Employee compensation: Wages, salaries, commissions, and benefits such as health and life insurance, retirement, and other forms of cash or non-cash compensation.

Employment: The number of jobs, including full-time, part-time, and seasonal positions. Employments can also be measured in full-time equivalents (FTE).

Imputed multiplier: The ratio of total economic effects divided by the direct effect for a given economic metric (e.g., output).

Indirect effects: Also called indirect market activity. The value of additional rounds of spending on input goods and services that are sourced from other industries in the economic region.

Induced effects: Also referred to as induced market activity. The value of spending that occurs by households working within directly and indirectly affected industries in the economic region. Induced effects are only present in models that have households endogenized, meaning that households are treated as productive/consumptive entities within the economic region.

Labor income: Measure of the income received by non-incorporated private business owners or self-employed individuals and the wages, salaries, commissions, and benefits that employees receive.

Leakages: The money that leaves the economic region through imports, taxes, or savings.

Other property income: Income received from investments such as corporate dividends, royalties, property rentals, or interest on loans.

Output: Describes the sales revenues associated with market activity and is comprised of the value of intermediate inputs (goods and services) as well as value added.

Proprietor income: Income received by non-incorporated private business owners or self-employed individuals.

Taxes on production and imports: Taxes paid to local, state, and federal governments including sales and excise taxes, customs duties, property taxes, motor vehicle licenses, severance taxes, other taxes, and special assessments. These taxes do not include income taxes.

Total effects: Also referred to as total market activity. The sum of direct, indirect, and induced (only in models with endogenized households) effects.

Value added: Broad measure of income, representing the sum of employee compensation, proprietor income, other property income, and indirect business taxes.

References

Botta, R., J. S. Borsum, E. V. Camp, C. D. Court, and P. Frederick. 2021. “Short-term economic impacts of ecological restoration in estuarine and coastal environments: a case study of Lone Cabbage Reef.” Restoration Ecology 3(1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13462

Botta, R., C. D. Court, and E. V. Camp. 2023. “Measuring the Short-Term Economic Impacts of Ecological Restoration” FE1133. EDIS 2023 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-FE1133-2023

Botta, R., C. D. Court, A. Ropicki, and E. V. Camp. 2021. “Evaluating the regional economic contributions of US aquaculture: Case study of Florida’s shellfish aquaculture industry.” Aquaculture Economics and Management 25 (2): 223–244 https://doi.org/10.1080/13657305.2020.1869860

Camp, E.V., Court, C.D., Ropicki, A. 2023. “Understanding Metrics for Communicating the Economic Value of Florida’s Fisheries and Coastal Resources” FA260. EDIS 2023 (5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fa260-2023

Miller, R., and P. Blair. 2022. Input-Output Analysis Foundations and Extensions (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108676212

Ropicki, A., E. V. Camp, C. D. Court, and R. Botta. 2022. “Understanding Metrics for Communicating the Importance of Florida’s Fisheries: Part III: Measuring Economic Value.” Manuscript in press.

United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA NASS). 2019. 2018 Census of Aquaculture, 2017. Census Agric. 3, AC-17-SS-2.

Watson, P., J. Wilson, D. Thilmany, and S. Winter, S. 2007. “Determining economic contributions and impacts: What is the difference and why do we care?” Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy 37:140–146.