Introduction

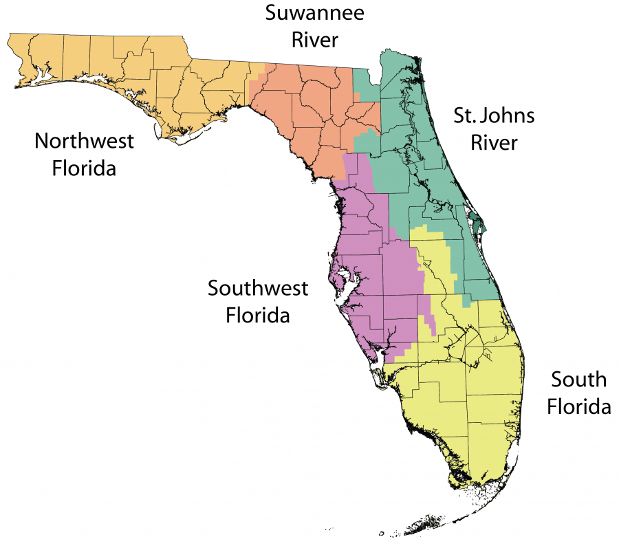

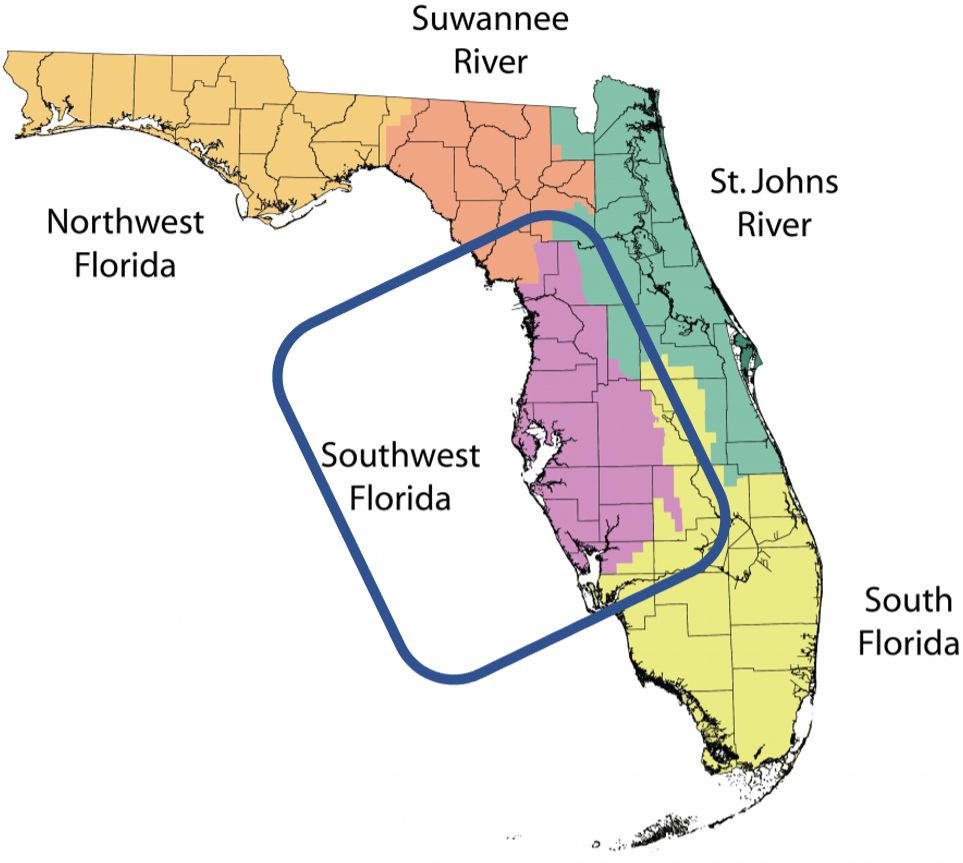

As a part of the EDIS series “Economic Value of Florida Water Resources,” this publication aims to help the interested public learn about the economic benefits associated with local water resources. It presents examples of the economic benefits of water resources in five Florida regions, which are generally defined based on the Water Management Districts’ boundaries (Figure 1).

Credit: Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP), https://floridadep.gov/water-policy/water-policy/content/water-management-districts#SJR

How can we measure the economic benefits provided by water resources?

Economists use various approaches to estimate the benefits of natural resources. For example, consider state and national parks in Florida organized around springs, rivers, or coastal attractions. Tourists are drawn by water-based recreation opportunities, the chance to see manatees, or enjoy other activities directly or indirectly associated with water. These visitors spend money on lodging, meals, snacks, or diving equipment, thereby supporting local businesses. The studies that examine the visitor spending and the economic activities spurred by this spending are referred to as “the economic impact analyses.” The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) annually analyzes the state parks' visitation, visitor spending, and related economic contribution. The National Park Service also publishes analyses of economic contributions for the national parks. University of Florida’s Economic Impact Analysis Program, as well as other Universities in the state, also examines economic contributions of visitor expenditures.

Another method to gauge the value assigned to water-related experiences is to ask visitors about their willingness to pay for various recreational experiences above their actual spending. Such an approach allows estimation of the values derived by visitors that are not captured in market transactions (referred to as “consumer surplus). Alternatively, this value can be examined by looking at how far tourists travel for recreational activities. One can also assess the benefits of water quality improvements by considering riverfront house sale prices during periods with “good” or “bad” river water quality. These and other methods to valuing the benefits provided by water resources are described in the overview publication in this series, here.

Studies report different estimates for the same site. Can I add up these estimates?

Sometimes the same recreational site or the same water body is examined repeatedly, frequently because of high regional or national significance. Economists can employ different valuation methods, focus on different types of benefits (e.g., recreation vs. riverfront property amenities), and employ various metrics (e.g., total recreational visitor spending vs. spending by non-local visitors only). To avoid possible double counting of the benefits, it is generally recommended to refrain from adding up different values estimated for the same site (even though there are exceptions to this general rule).

Northwest Florida: State Parks and Visitors’ Spring-Based Recreation

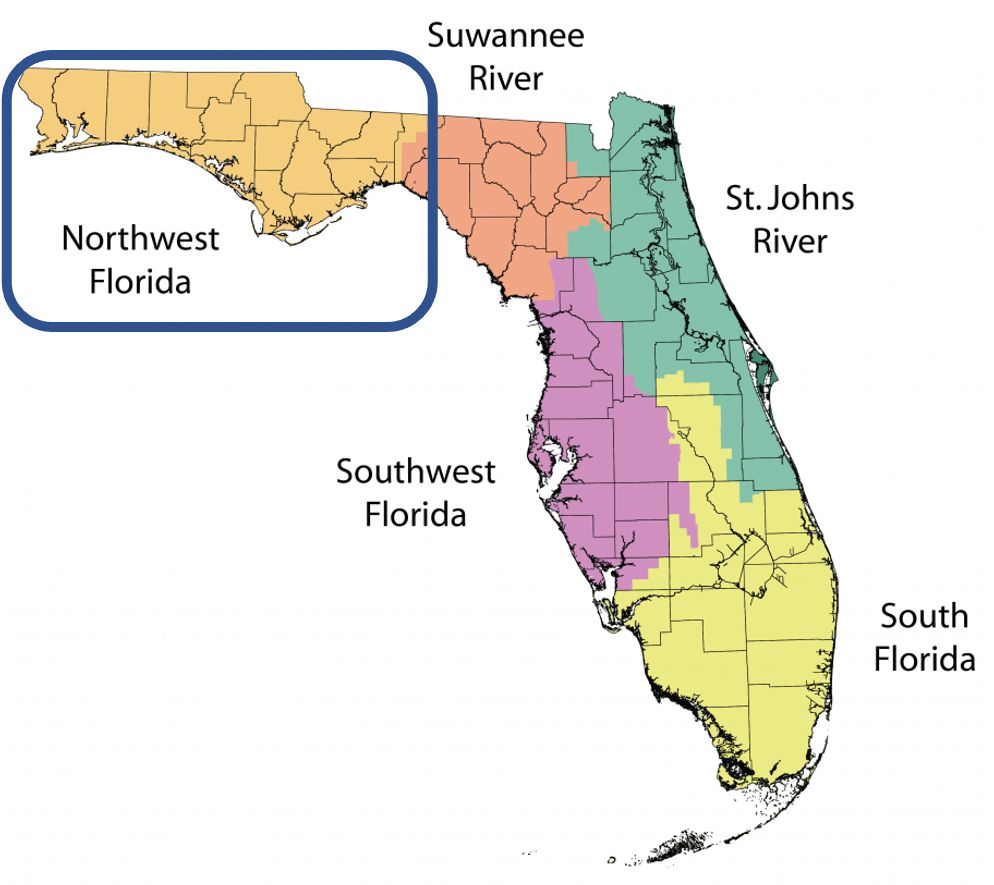

The Florida Panhandle (Figure 2) is recognized for its freshwater springs and rivers. Both coastal and inland state and national parks contribute significantly to the regional economy (Table 1). For example, the estimated economic contribution for Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park was $19.7 million in 2019, supporting 276 full- and part-time jobs.

Credit: Based on FDEP 2017

Credit: NWFWMD

Further, the value of recreational experiences to the visitors was estimated for recreation on Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park, Jackson Blue Springs County Recreation Area, and sites in the Apalachicola River Basin (Table 2). For example, cave diving trips to the Jackson Blue Springs County Recreation Area are valued by the visitors at $155 per person per trip (above the actual trip expenditures). These estimates illustrate the importance of protecting local water resources.

Table 1. Economic studies examining recreational benefits provided by water resources in the NWFWMD.

Table 2. Visitors’ willingness to pay (WTP) above the actual spending for recreational trips in the NWFWMD.

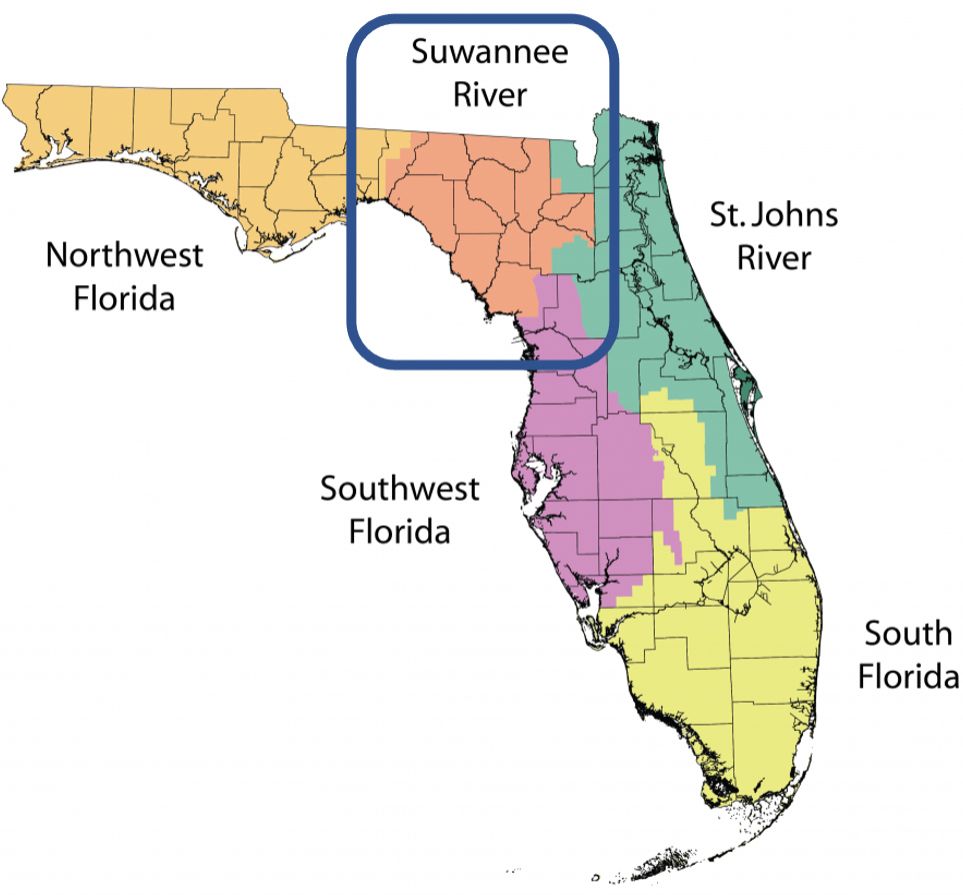

Suwannee River Basin: Florida’s Springs Region

Springs are unique natural landmarks in north Florida, attracting many recreational visitors and supporting local economies. The Suwannee River Water Management District (Figure 4) has one of the highest concentrations of large freshwater springs in the United States (SRWMD undated). These large springs are referred to as first- and second-magnitude springs for the large volumes of water they discharge – more than ten or even 100 cubic feet per second. For example, Figure 5 shows Blue Hole at Ichetucknee Springs, one of Florida's large springs, located in the District. Spring recreational and wildlife depend on the water flow and good water quality, and stakeholder groups and agencies are working on restoring or protecting this unique natural resource. Reduction in spring water quality and flow is a concern for many.

Credit: Based on FDEP 2017

Several studies estimated the spending of visitors to the springs and related this spending to regional economic activities. For example, 258,000 people attended Ichetucknee Springs State Park in 2019, contributing $21.7 million to the regional economy, and supporting 304 jobs (Table 3).

In addition, Wu et al. (2018) examined the visitors’ willingness to pay for their recreational experiences in addition to the expenses incurred. For example, for Ichetucknee Springs, Wu et al. (2018) estimated that the value of the visitors' recreational experiences was $14.66 million above the actual trip expenditures (Table 4).

Overall, these studies imply that deteriorating quality and reducing flows of the springs may result in a significant reduction in springs-related expenditures and thereby economic activity in the region and the loss of recreational opportunities and related benefits highly valued by the visitors.

Table 3. Economic studies examining recreational benefits provided by water resources in the SRWMD.

Table 4. Recreational benefits provided by water resources in the SRWMD: value beyond actual visitor spending.

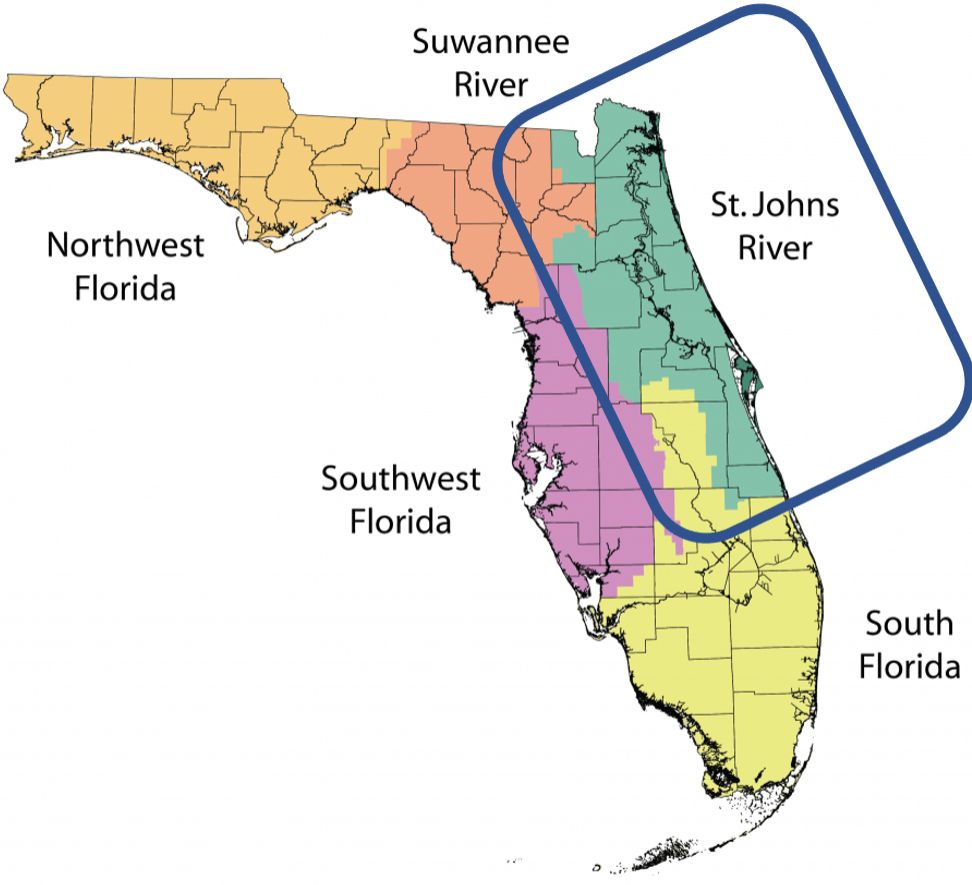

East Florida: Diverse Water Resources and Related Benefits

Diverse water resources in east Florida, broadly defined as the area of St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD, see Figure 6), provide residents and visitors with various recreational opportunities (Figure 7), waterfront amenities, and other benefits. The studies focusing on the economic impact of recreational benefits specifically are summarized in Table 5. For example, Blue Spring State Park was visited by more than 560,000 visitors in 2019, contributing almost $49 million to the regional economy, and supporting 572 full-time and part-time jobs. In addition to the actual expenditure for the recreational trips (and related contribution to state economy), the value derived by the visitors to all inland water recreation sites in the region was estimated at $208.9 million per year (Table 6).

Credit: Based on FDEP 2017

Credit: UF/IFAS

One of the largest cities in Florida and the United States, Jacksonville, is located in SJRWMD. It is not surprising that several economic studies conducted in this region focused on the value of clean water to residential households in Jacksonville and the surrounding area. Studies showed that improving river or lake water quality increases waterfront homes' prices, reflecting the worth of the enhanced amenity benefits provided by the water bodies (Table 7). Two other studies found that households are willing to pay for improved water quality for domestic use (Table 8). Overall, protecting and improving water quality and availability in rivers, lakes, and aquifers ultimately impacts locals' and visitors' well-being.

Table 5. Economic impact of water-based recreational in east Florida.

Table 6. Visitors’ willingness to pay (WTP) above the actual spending for the recreational trip.

Table 7. Economic studies focusing on amenity values provided by water resources in east Florida.

Table 8. Economic studies focusing on the value of water quality Improvements in east Florida.

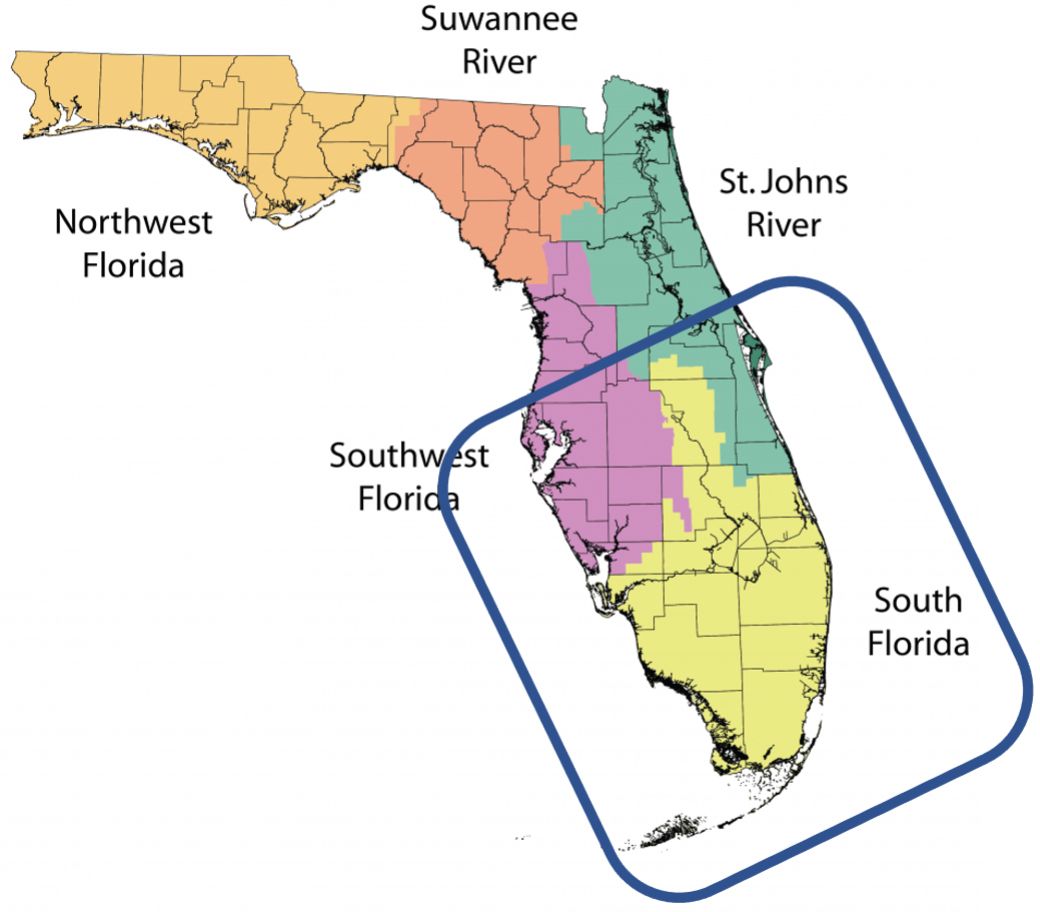

West-Central Florida: Visitation of Coastal and Inland State Parks

Inland springs and coastal areas in southwest Florida (Figure 9) attract many visitors annually, and visitors’ spending is an important contributor to the region’s economy. For example, more than 350 million people visited Rainbow Springs State Park in 2019, contributing $31.1 million to the economy and supporting 436 full- and part-time jobs (Table 9). Deterioration of water resources can result in a significant reduction in recreational activity and related economic contributions in the region. More studies are underway to measure these impacts. For example, in 2020, the National Center for Coastal Ocean Science awarded a grant to study the economic impacts of the historic harmful algal bloom (commonly referred to as “red tide”) in 2017–2019. Economists from major Florida universities lead the study, and study results should become available soon (NCCOS 2020a, NCCOS 2020b).

Credit: Based on FDEP 2017

Credit: Based on FDEP 2017

Table 9. Economic studies examining recreational benefits provided by water resources in the SWFWMD.

South Florida: The Everglades and Other State and National Parks

Wise management of water resources is crucial for the south Florida region (Figure 10). The studies conducted in the region focused on the following types of important “services” provided by natural resource sites: (a) recreation (with visitors’ spending contributing to the regional economy, Table 10); (b) amenity provided by the waterfront properties, with the amenity impacted by river and estuary water quality changes (Table 11); and (c) variety of services provided by the Everglades, such as wildlife habitat and ecosystem function support (Table 12).

Credit: UF/IFAS

State parks and national preserves attract millions of people annually, and this visitation is essential for local business activities. Water quality in coastal waters can also significantly impact beachfront properties' attractiveness (and related tax collections). Preservation of wildlife habitat, water flow regulation, carbon sequestration, and other benefits provided by south Florida wetlands are also valued by many. Changes in these services will have an indirect but possibly significant influence on people's well-being. Future studies will provide additional estimates in support of this statement. For example, in 2020, the National Center for Coastal Ocean Science awarded a grant to study the economic impacts of the historic harmful algal bloom (commonly referred to as “red tide”) in 2017–2019. Economists from major Florida universities lead the study, and study results should become available soon (NCCOS 2020a, NCCOS 2020b).

Table 10. Economic value of services provided by water resources in the SFWMD.

Table 11. Examples of amenity values provided by water resources.

Table 12. Examples of the values of supporting and regulating ecosystem services provided by water resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding for the project “Water resources and human society: educating Floridians about the value of water resources” from UF Thompson Earth Systems Institute (TESI): Earth Systems Grants. TESI aims to support projects by UF students and postdoctoral scholars that communicate Earth systems research to the institute’s audiences. See more at: TESI, https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/earth-systems/blog/announcing-the-2018-ties-grant-recipients/. This work is also partially funded by USDA NIFA National Integrated Water Quality Program Award No. 2014-51130-22495 (PI: Kelly Grogan).

References

Alongi, D. 2012. “Carbon Sequestration in Mangrove Forests.” Carbon Manage 3:313–322.

Alavalapati, J. R. R., R. K. Shrestha, G. A. Stainback, and J. R. Matta. 2004. “ Agroforestry Development: An Environmental Economic Perspective.” Agroforestry Systems 61:299–310.

Bin, O., and J. Czajkowski. 2013. “The Impact of Technical and Non-Technical Measures of Water Quality on Coastal Waterfront Property Values in South Florida.” Marine Resource Economics 28 (1): 43–63.

Bin, O., J. Czajkowski, J. Li, and G. Villarini. 2017. “Housing Market Fluctuations and the Implicit Price of Water Quality: Empirical Evidence from a South Florida Housing Market.” Environment & Resource Economics 68 (2): 319–341.

Borisova, T., A. Hodges, and T. Stevens. 2015. Economic Contributions and Ecosystem Services of Springs in the Lower Suwannee and Santa Fe River Basins of North-Central Florida. https://fred.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/economic-impact-analysis/FE958.pdf

Chaikaew, P., A. Hodges, and S. Grunwald. 2017. “Estimating the Value of Ecosystem Services in a Mixed-Use Watershed: A Choice Experiment Approach.” Ecosystem Services 23:228–237.

Chatterjee, C., R. Triplett, C. K. Johnson, and P. Ahmed. 2017. “Willingness to Pay for Safe Drinking Water: A Contingent Valuation Study in Jacksonville, FL.” Journal of Environmental Management 203: 413–421.

East Central Florida Regional Planning Council and Treasure Coast Regional Planning Council (ECFRPC and TCRPC). 2016. Indian River Lagoon Economic Valuation Update. https://loveourlagoon.com/IRL-Economic-Valuation-Update-07252016.pdf

Ehrlich, O., X. Bi, T. Borisova, and S. Larkin. 2016. A Latent Class Analysis of Public Attitudes toward Water Resources with Implications for Recreational Demand. Retrieved from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/230058

Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). 2018. Florida Park Service State Parks Map. https://www.floridastateparks.org/statewide-map

Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). 2017. Water Management Districts. https://floridadep.gov/water-policy/water-policy/content/water-management-districts

Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). 2020. Economic Impact Assessment – Florida State Park System. https://floridadep.gov/sites/default/files/2019-2020%20EIA%20Report%20FINAL%20and%20COVER%20MEMO.pdf

Guignet, D., P. J. Walsh, and R. Northcutt. 2016. “Impacts of Ground Water Contamination on Property Values: Agricultural Run-off and Private Wells.” Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 45 (2): 293–318.

Huth, W. L., and O.A. Morgan. 2011. “Measuring the Willingness to Pay for Cave Diving.” Marine Resource Economics 26:151–166. http://www.agnesmilowka.com/ag_media/coverage/agecon-06-morgan-c.pdf

Milon, J. W., and D. Scrogin. 2006. “Latent Preferences and Valuation of Wetland Ecosystem Restoration.” Ecological Economics 56 (2): 162–175. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800905000571

Morgan A.O. and W.L. Huth. 2011. Using revealed and stated preference data to estimate the scope and access benefits associated with cave diving. Resource and Energy Economics 33:107–118. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0928765510000072

National Center for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS). 2020a. Assessment of the Short- and Long-Term Socioeconomic Impacts of Florida’s 2017–2019 Red Tide Event. https://coastalscience.noaa.gov/project/assessment-of-the-short-and-long-term-socioeconomic-impacts-of-floridas-2017-2019-red-tide-event/

National Center for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS). 2020b. Estimating Economic Losses and Impacts of Florida Red Tide. https://coastalscience.noaa.gov/project/estimating-economic-losses-and-impacts-of-florida-red-tide/

National Park Services. 2020. Visitor Spending Effects - Economic Contributions of National Park Visitor Spending. https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/06-11-20-nps-visitor-spending-generates-economic-impact-of-more-than-41-billion.htm

Suwannee River Water Management District (SRWMD). Undated. Springs. https://www.mysuwanneeriver.com/267/Springs

Seidel, V., W. Milon, A. Baker, and C. Diamond. 2015. Economic Impact of the St. Johns Water Quality on Property Values. In: Hacner, C.T (ed). Sr. Johns River Economic Study. Report submitted to the St. Johns River Water Management District under contract#27884.

Shrestha, R. K., T. V. Stein, and J. Clark. 2007. “Valuing Nature-Based Recreation in Public Natural Areas of the Apalachicola River Region, Florida.” Journal of Environmental Management 85: 977–985.

Wu, Q., X. Bi, K. Grogan, and T. Borisova. 2018. “Valuing Recreation Benefits of Natural Springs in Florida.” Water 10 (10): 1379. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/10/10/1379