Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Citrus Research and Development Foundation project award 18-059C, “Citrus Row Middle Management to Improve Soil and Root Health.”

Introduction

Florida has historically been the largest producer of oranges in the United States. However, citrus production has consistently decreased since the detection of huanglongbing (HLB), or citrus greening disease, in the state in 2005. While Florida produced more than 70% of US oranges in 2005–06, California became the largest producer in 2022–23 (USDA-NASS, 2024b). Frequent catastrophic hurricanes have also worsened the strained citrus industry. For instance, the citrus industry is still recuperating from the aftermath of Hurricane Ian, which wreaked havoc on the citrus-growing regions of the state in September 2022. The total on-tree value of production decreased from $205.2 million in 2021–22 to $137.5 million in the 2022–23 growing season (USDA-NASS 2024b). Furthermore, the forecast for the 2023–24 season, which is 18 million boxes, is less than half of what was produced in 2021–22 (USDA-NASS 2024a). In the backdrop of uncertainties and adverse growing conditions and given that soils in Florida are sandy and have low organic matter, citrus growers in the state could adopt cover crops to improve soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and beneficial microbial activity (Castellano-Hinojosa et al. 2022; Strauss and Albrecht 2018) to improve the general growing conditions in their groves.

Cover crops are non-cash crops typically grown in row crop production systems for their soil health and environmental benefits. Since cover crop adoption in fruit production systems is uncommon, Chakravarty and Wade (2023) is one of few studies that estimated their adoption costs. This document summarizes the methods and findings used to assess the potential profitability of cover crop adoption in citrus row middles. The information provided may be valuable to citrus and other tree crop growers interested in understanding the costs of growing cover crops. It may also benefit Extension agents and professionals who advise growers on conservation practices, as well as decision-makers involved in cost-share programs or other payment incentives for cover crop adoption.

We present results from a static one-year cost analysis assessing the viability of cover crops in a typical Florida citrus grove. The primary objective is determining whether planting cover crops in citrus row middles is economically feasible for citrus growers. Specifically, we developed a partial budget for cover crops for a typical Florida orange grove. We calculated breakeven prices for sweet oranges in terms of price per box (equivalent to 90 lbs of oranges) and price per pound solids (amount of soluble solids per box of oranges) while also incorporating additional net costs associated with growing cover crops in citrus groves across historical yield and quality scenarios. Given that cover crops are effective in improving soil quality and suppressing weed growth and have short-term savings in the form of reduced mowing, we believe that the results from our study will benefit citrus growers considering planting cover crops in their grove row middles.

Cover Crops in Citrus

Cover crops have traditionally been used in row crop agriculture to improve soil health, reduce soil erosion, control nutrient leaching, increase the population of beneficial arthropods, and suppress weeds (Klonsky and Tourte 1997). Although cover crop adoption is not common in horticultural crop production systems, they have been adopted in some tree crops such as apples and almonds (Wilson et al. 2022; Pavek and Granatstein 2014). Recent research at experimental citrus groves in South Florida indicated that incorporating cover crops into the row middles enhanced soil carbon and nitrogen availability within one year, along with changes in the soil microbiome (Castellano-Hinojosa and Strauss 2020). Furthermore, given Florida soils' inherently low nitrogen levels, organic matter, and water retention capacity, various cover crop blends can offer grove-specific advantages depending on local soil and ecological conditions. For instance, combining legume and non-legume cover crops can enhance nitrogen fixation and reduce nitrous oxide emissions from the soil (Castellano-Hinojosa et al. 2022). Additionally, cover crops have demonstrated efficacy in reducing weed density by outcompeting weeds for nutrients, light, and moisture (Linares et al. 2008; Strauss et al. 2019). Therefore, integrating cover crops into citrus production systems can benefit growing conditions, thus potentially alleviating some of the detrimental impacts of HLB infections on citrus tree health.

Methodology and Assumptions

Cover crop management and costs are additional to typical cultural practices in citrus production with one deviation: reduced mowing since citrus row middles will not need to be mowed. Thus, our analysis begins with the cost of conventional citrus production, to which we add the cost of cover crop management. Once total costs are estimated, we subtract the mowing costs and use yields to evaluate breakeven prices given historical yield and quality information.

Cost of Conventional Citrus Production

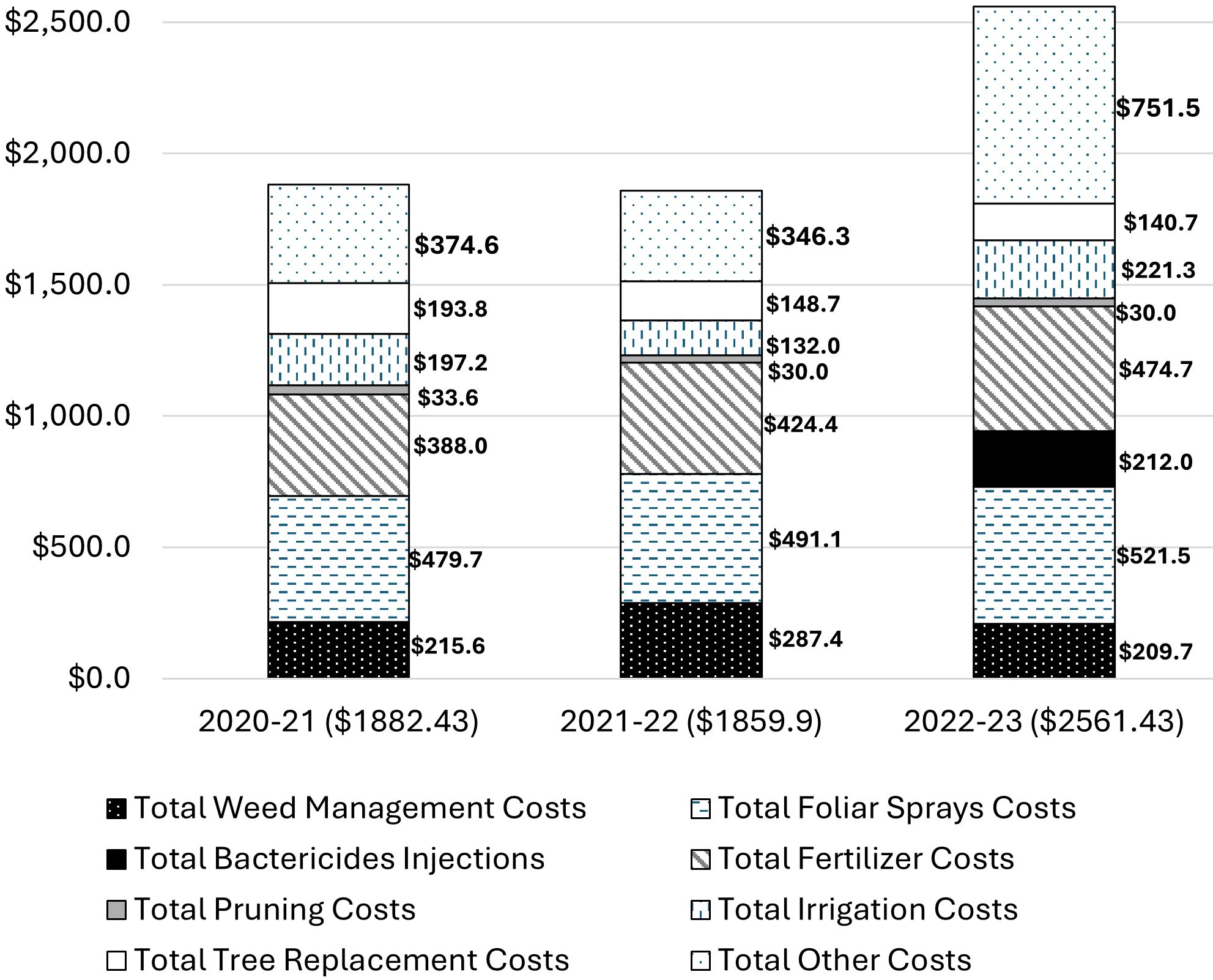

Benchmark costs for a conventional 10-year-old orange grove in the state's southwest region in 2022–23 were sourced from Singerman (2023a). These are the most reliable estimates for the region since production practices are similar, there are no recent estimates for the central and ridge regions, and the budgets for the Indian River region are for grapefruits. The total cost of production of orange was $2,561.43/acre.

The total orange production costs breakdown by major categories for the 2020–21, 2021–22, and 2022–23 growing seasons is presented in Figure 1 (Singerman 2022a, 2022b, 2023a). As a note, the cost of production of oranges increased by 26%–28% in 2022–23 from the 2020 and 2021 seasons. This cost increase is comparable to the 30% increase in Valencia orange producer price index (PPI) between June 2021–May 2022 and June 2022–May 2023 (BLS 2023). A comparison of the input costs revealed two important facts. First, the proportion of “Total other costs,” which included the interests on capital investment, increased to 29.3% in 2022–23 from 18.6% in 2021–22 and 19.9% in 2020–21. Second, growers in 2022–23 started using Oxytetracycline (OTC) trunk injections post Special Local Needs (SLN) approval for two OTC formulations by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Except for the “Total weed management costs” and “Total tree replacement costs,” all other major cost items increased. However, their proportions with respect to the total production cost decreased, indicating that growers might have cut down on these costs to compensate for the increased interest payment costs and the adoption of new OTC trunk injection technologies.

Cover Crops Adoption Costs

Cover crops represent an additional cost to traditional grove management. Our cost estimates for incorporating cover crops into citrus row middles were based on discussions with two commercial growers in southwest Florida. One managed less than 50 acres, while the other had between 150 and 200 acres across Charlotte and Polk counties. In this region, it is recommended to plant cover crops in June and November.

Table 1 shows the breakdown of cover crop costs per acre. The primary cover crops cost categories in our partial budget are seed costs, fuel costs, labor costs, cost of a no-till drill, and other miscellaneous costs:

- Cover crop seeds ($160 per acre per year): Four common types of cover crops were considered: common sunflower (Helianthus annuus), daikon radish (Raphanus sativus), buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum), and the legume sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea). The seeding rate ranged from 50 to 80 pounds per acre, averaging 65 pounds per acre. To estimate the cost of seeds, we averaged the prices available online from two seed companies, resulting in an estimated $1.523 per pound or $99 per acre per application. Since cover crops seeds were planted twice annually, the total cost amounted to $198 per acre. We assigned equal weightage to all seed types to create a budget reflective of a typical farm, considering seed availability can vary over time and by location. Therefore, our cost estimates are based on an average of several cover crop varieties.

- Labor ($12 per acre per year): The labor cost estimate of $22.80 per hour was the average hourly wage rate for general labor in the central Florida (Ridge), Indian River, and southwest Florida regions for 2022–23 (Singerman 2023b). Growers indicated it took a worker around 0.267 hours (about 16 minutes) to complete planting an acre of grove. This translates to a labor cost of $6 per acre per application or $12 annually.

- Fuel ($6.40 per acre per year): To estimate fuel costs, we averaged retail prices of Diesel Ultra Low Sulfur in the lower Atlantic region from June 2022 through May 2023 using data from the US Energy Information Administration (USEIA) (US-EIA 2023). The calculated average was $4.80 per gallon, which aligned closely with the fuel costs reported by growers. We found that approximately 0.6667 gallons of diesel fuel are required per acre of citrus grove. Thus, fuel costs would be approximately $3.20 per acre per use or $6.40 annually.

- No-till drill ($30 per acre per year): Using a no-till drill for seeding significantly improved seeding rates relative to broadcasting. Since this is a new practice for many citrus growers, we expect they will choose to rent this equipment. As no publicly available data on no-till drill rental rates in Florida were found, we used rental rates from Georgia Conservation Districts, which range from $15 to $30 per acre annually. This rate is reasonable, as equipment costs in Florida are comparable to, or slightly higher than, those in Georgia.

- Miscellaneous ($5 per acre per year): We included a $5 per acre miscellaneous cost to account for the learning curve of growers adopting new practices such as cover crops in citrus production. This cost reflects potential additional expenses incurred as growers refine their cover crop mix to suit their soil type or adjust planting schedules based on factors like precipitation levels.

The total cost of using cover crops in citrus was thus $251.40/acre per year. Adding this to other production costs, we calculated $2,812.83/acre per year as the total cost of production for both varieties of oranges when cover crops were used (Table 1).

Savings from Reduced Mowing

Reduced mowing is the immediate benefit of planting cover crops in row middles. Not mowing saves on mowing costs and keeps the ground covered, which helps preserve soil structure (Strauss and Albrecht 2018). Additionally, since cover crops suppress weeds, there is no need for chemical mowing, which is typically used for weed control. Cover crops are also thought to improve nutrient availability in the long term. We did not consider cost savings from reduced fertilizer and herbicide use in citrus groves, as current research on citrus did not provide those estimates. Moreover, herbicides for weed management are mainly used under trees, where the cover crops are not grown. The average savings from not mowing row middles is $33.24 per acre. Note that mowing practices have changed recently. The 2022–23 budget for orange production included two mowing applications for weed control instead of the 6–8 applications in previous years (Singerman 2022a; 2022b; 2023a). Thus, the total mowing cost was significantly less in the 2022–23 growing season.

When factoring in the savings from not mowing, the net cost of cover crops for citrus is $218.16, and the total production cost of citrus with cover crops in the row middles is $2,779.59 per acre. Cover crop costs represent an 8.52% increase from the original production cost and account for 7.85% of the total production cost.

Yield

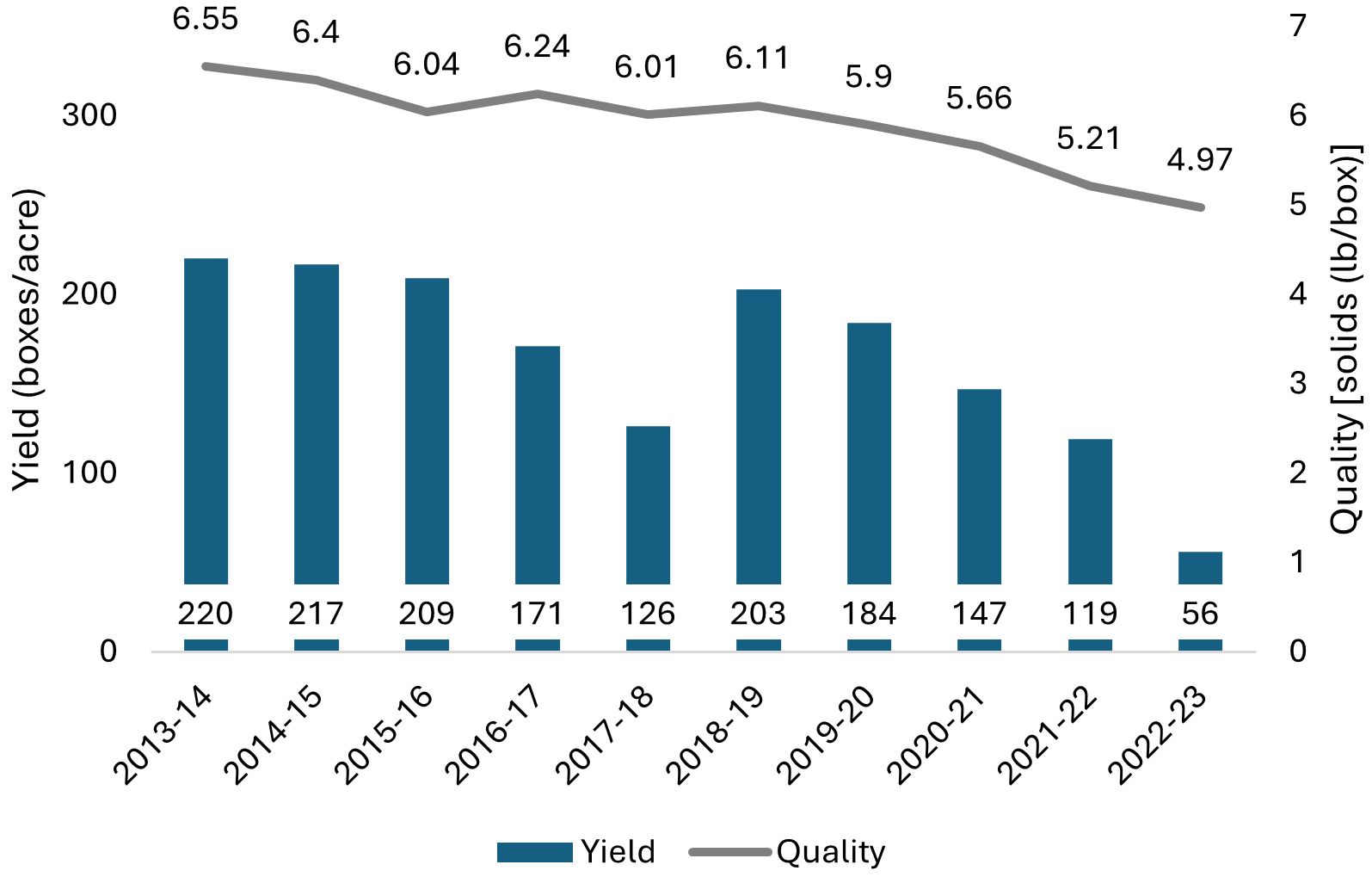

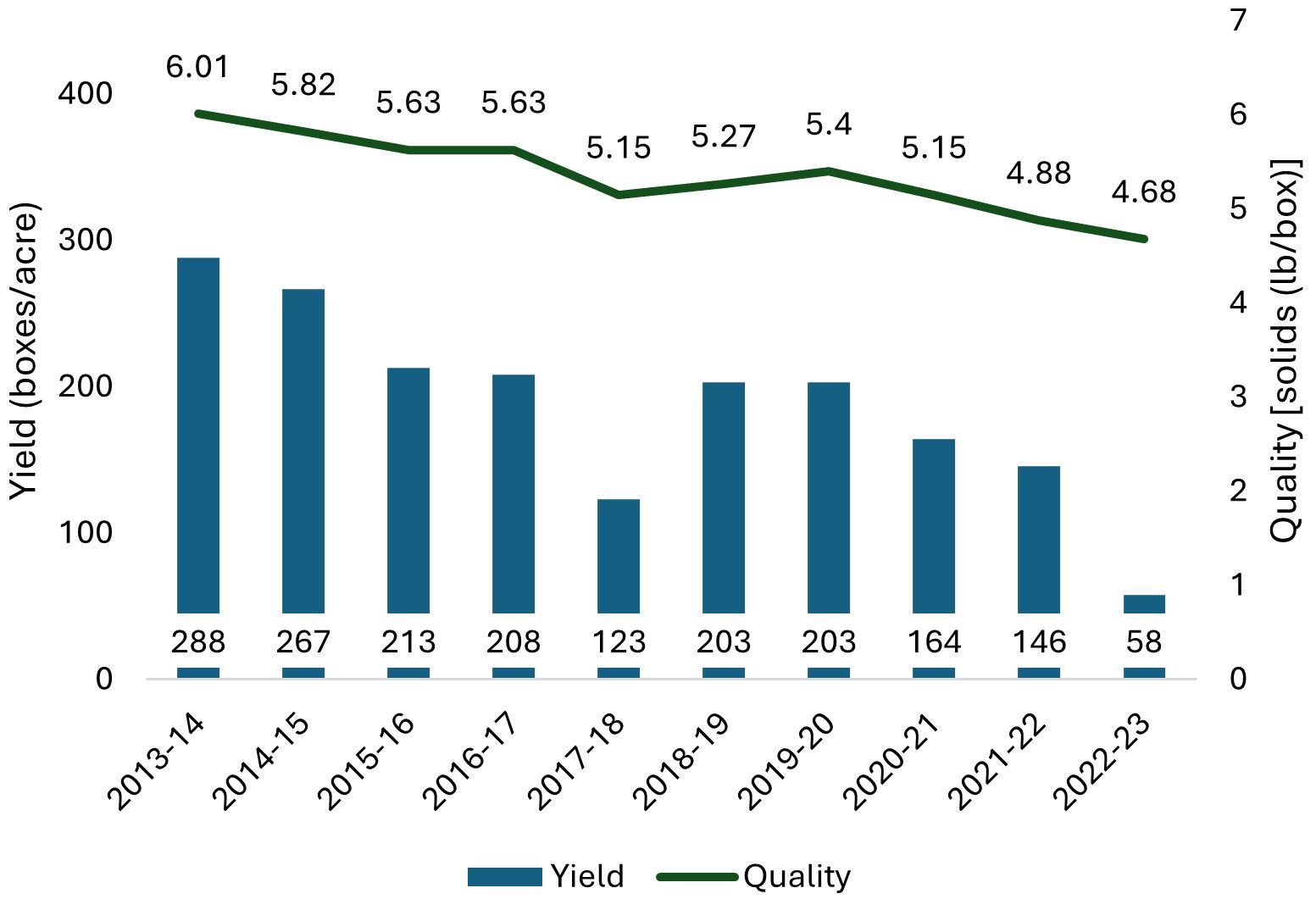

Historical yield data (boxes per acre) were from the USDA-National Agricultural Statics Services (USDA-NASS) and cover the period from 2013–14 to 2022–23 (USDA-NASS 2024). Quality data (pounds solids per box) for the same period were from the Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC) (FDOC 2023b), as well as price per box and price per pound solids for non-'Valencia' oranges (FDOC 2023a) and 'Valencia' oranges (FDOC 2023b). Figures 2 and 3 depict the temporal changes in yield and quality for 'Valencia' and non-'Valencia' oranges, respectively.

Credit: Yield data are from US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistical Service (USDA-NASS 2024), and quality data are from Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC 2023b).

Credit: Yield data are from US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistical Service (USDA-NASS 2024), and quality data are from Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC 2023a).

Yields have consistently declined since the 2013–14 season. Although yields improved following Hurricane Irma in 2018–19, they resumed their downward trend, plummeting in the Hurricane Ian-affected 2022–23 season. Quality followed a similar pattern (Figures 2 and 3). A strong positive correlation exists between yields and quality with correlation coefficients of 0.88 for 'Valencia' oranges and 0.94 for non-'Valencia' oranges. However, yield fluctuations were more pronounced. For example, 'Valencia' orange yields peaked at 220 boxes per acre in 2013–14 and fell to a low of 56 boxes per acre in 2022–23. Quality reached a high of 6.55 pounds solids per box in 2013–14 and a low of 4.97 pounds solids per box in 2022–23. Yields demonstrated greater variability relative to their average compared to quality. Additionally, non-'Valencia' orange yields exhibited higher variability than those of 'Valencia' oranges.

We considered the minimum, 1st quartile, median/2nd quartile, 3rd quartile, and maximum values for yield and quality to construct our yield-quality scenarios. We calculated the breakeven delivered-in prices considering the total delivered-in cost of oranges, including the pick and haul charge of $4.46 and $4.17 per box for 'Valencia' and non-'Valencia' oranges, respectively, along with the FDOC assessment charge of $0.12 per box of oranges (Singerman 2023a).

Results and Discussion

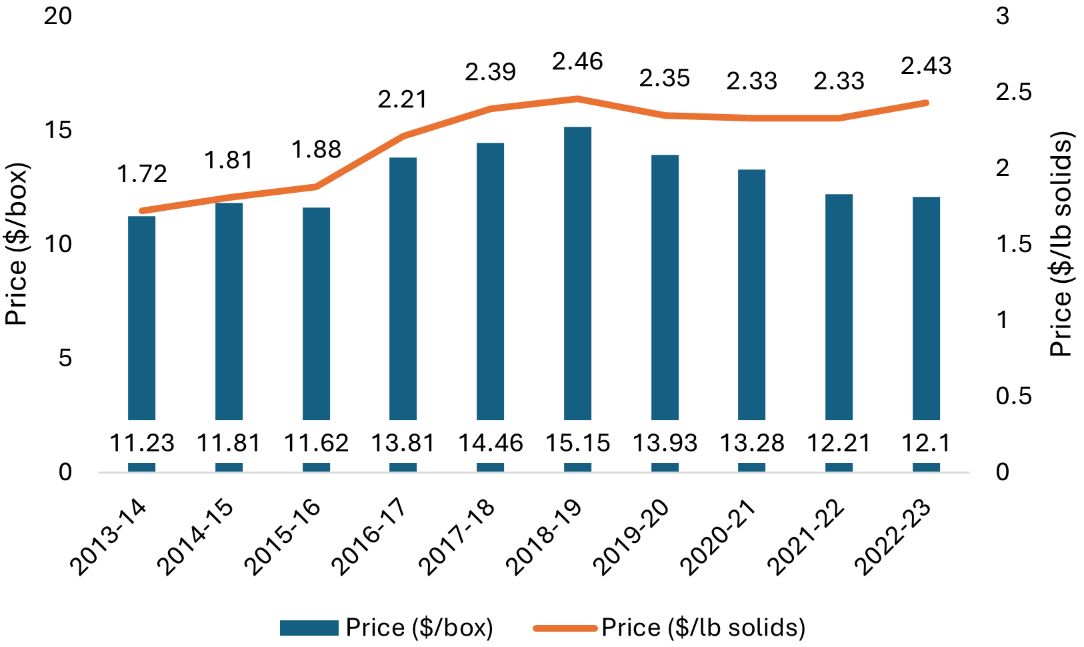

The breakeven price estimates for 'Valencia' and non-'Valencia' oranges, across various yield-quality scenarios, are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. While the breakeven price per box is independent of quality, prices per pound solids are influenced by quality, with higher quality resulting in lower breakeven prices. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate historical price trends for both types of oranges.

Credit: Price data are from the Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC 2023b).

Credit: Price data are from the Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC 2023a).

For ‘Valencia’ oranges, breakeven prices ranged from $54.22 per box for the minimum historical yield in 2022–23 to $17.20 per box for the maximum yield (Table 2). Since the effects of weather-induced yield shocks, like hurricanes, can persist for several years, future yields likely lie between 56 boxes per acre (the minimum, with a breakeven price of $54.22 per box) and 131.3 boxes per acre (the 1st quartile, with a breakeven price of $25.76 per box). These prices are notably higher than the highest per-box prices reported by FDOC (see Figure 4). The quality of 'Valencia' oranges, measured in terms of pounds solids per box, has declined since the post-Irma peak of 6.11 pounds solids per box in 2018–19. The 2022–23 season saw the lowest quality, with 4.97 pounds solids per box. Thus, given the low yield and quality estimates in recent years and based on the historical yield and quality levels examined, it will not be profitable to adopt cover crops in ‘Valencia’ orange production in the short run. With the per box price of $12.10 in 2022–23 (FDOC 2023b), a back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that a Valencia grove should yield almost 230 boxes per acre to break even with cover crops.

For non-'Valencia' oranges, the breakeven prices per box range from $52.21 for the lowest yield of 58 boxes per acre to $13.94 for the highest yield of 288 boxes per acre (see Table 3). In the 2022–23 and 2021–22 growing seasons, yields were 58 and 146 boxes per acre, falling between the minimum and the 1st yield quartiles. Quality levels have also been at their lowest after Hurricane Ian. For any yield and quality levels recorded since 2014–15 (Figure 2), the breakeven prices in Table 3 exceed the highest recorded price of $2.41 per pound solids in 2016–17 (Figure 5). These findings indicate that introducing cover crops in non-'Valencia' orange production may not be financially feasible based on the yield and quality levels observed over the past nine years. However, at the highest yield quartile (288 boxes per acre) and quality (6.01 pounds solids per box), which align with levels seen in the 2013–14 season, the breakeven price is lower than the highest price recorded over the past decade, observed in the 2016–17 season. For ‘non-Valencia’ groves to break even, the yield should be 263.20 boxes/acre.

Conclusion

The main challenge for citrus growers is maintaining yield and quality in the face of ongoing issues caused by HLB and extreme weather events such as hurricanes. While the immediate effect of adopting cover crops on fruit yield and quality may not be substantial, their well-documented benefits for soil health could lead to better yields and quality over time. As such, incorporating cover crops into citrus farming practices could be a viable long-term strategy, although outcomes may vary depending on soil and growing conditions in individual groves. Growers will have to evaluate whether, in their particular situation, the benefits in terms of improved soil health and potential increases in yield and quality will more than offset the increase in overall grove production costs. In the first year of adoption, cover crops increase per-acre production costs by 8.52%, representing 7.85% of the total production cost.

Yields and quality of 'Valencia' and non-'Valencia' oranges have decreased, particularly during the 2020–21 and 2021–22 seasons, with a notable drop following Hurricane Ian in 2022. Given these recent trends, adopting cover crops may not be financially beneficial for these crops at this time. Our study provides an upper estimate of the costs associated with growing cover crops in citrus production systems.

Additional Resources

The authors prepared a “Cover Crops Planning Tool for Citrus Production” and made it available in the Cover Crop Planning Tools section at swfrec.ifas.ufl.edu. This is an Excel workbook that interested readers can use to estimate cover crop costs and make decisions on profitability in their operations. The values provided are estimates. Users will need to consult their budgets and management needs before making decisions on growing cover crops.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. Producer Price Indexes. https://www.bls.gov/ppi/data-retrieval-guide/home.htm

Castellano-Hinojosa, A., and S. L. Strauss. 2020. “Impact of Cover Crops on the Soil Microbiome of Tree Crops.” Microorganisms 8 (3): 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030328

Castellano-Hinojosa, A., W. Martens-Habbena, and S. L. Strauss. 2022. “Cover Crop Composition Drives Changes in the Abundance and Diversity of Nitrifiers and Denitrifiers in Citrus Orchards with Critical Effects on N2O Emissions.” Geoderma 422:115952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.115952

Chakravarty, S., and T. Wade. 2023. “Cost Analysis of Using Cover Crops in Citrus Production.” HortTechnology 33 (3): 278–285. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05126-22

Florida Department of Citrus. 2023a. “Early Mid Season Final Field Box Reports.” https://fdocgrower.app.box.com/s/6ztwss8m7bkxmjsn4mq2trw19n0ev54j/folder/33385298357

Florida Department of Citrus. 2023b. “Late Season Final Field Box Reports.” https://fdocgrower.app.box.com/s/6ztwss8m7bkxmjsn4mq2trw19n0ev54j/folder/33385359718

Georgia Association of Conservation Districts. 2023. “District Equipment Rental.” https://www.gacd.us/equipment

Klonsky, K., and L. Tourte. 1997. “Production Practices and Sample Costs for Fresh Market Organic Valencia Oranges: South Coast—1997.” 1997 Ventura County Organic Oranges Cost and Return Study by the University of California Cooperative Extension. Accessed September 2025. https://coststudyfiles.ucdavis.edu/uploads/cs_public/b5/c3/b5c3979d-7898-42a9-aaf0-09d40ced50e0/97orgorange.pdf

Linares, J., J. Scholberg, K. Boote, C. A. Chase, J. J. Ferguson, and R. McSorley. 2008. "Use of the Cover Crop Weed Index to Evaluate Weed Suppression by Cover Crops in Organic Citrus Orchards.” HortScience. 43 (1): 27–34. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.43.1.27

Pavek, P. L. S., and D. M. Granatstein. 2014. “The Potential for Legume Cover Crops in Washington Apple Orchards.” USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Plant Materials Technical Note No. 22. 34 pp. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/plantmaterials/wapmctn12149.pdf

Singerman, A. 2022a. “Cost of Production for Processed Oranges in Southwest Florida in 2020/21: FE1111, 02 2022.” EDIS 2022 (1). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fe1111-2022

Singerman, A. 2022b. “Cost of Production for Processed Oranges in Southwest Florida in 2021/22.” https://crec.ifas.ufl.edu/media/crecifasufledu/economics/2021_22-SW-Costs-20220620.pdf

Singerman, A. 2023a. “Cost of Production for Processed Oranges in Southwest Florida in 2022/23.” https://crec.ifas.ufl.edu/media/crecifasufledu/economics/2022_23_SW-Costs_20231114.pdf

Singerman, A. 2023b. “Summary of 2022/23 Central Florida (Ridge) and Indian River-Southwest Florida Citrus Custom Rate Charges.” https://crec.ifas.ufl.edu/media/crecifasufledu/economics/docs/2022_23_CaretakerRates_20230808.pdf

Strauss., S. L., and U. Albrecht. 2018. “Components of a Healthy Citrus Soil.” Citrus Industry Magazine November 2018. http://citrusindustry.net/2018/11/09/components-of-a-healthy-citrus-soil/

Strauss., S. L., D. Kadyampakeni, R. Kanissery, and T. Wade. 2019. “Cover Crops for Citrus.” Citrus Industry Magazine April 2019. http://citrusindustry.net/2019/04/09/cover-crops-for-citrus/

US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS) 2024a. “Citrus March Forecast: Maturity Test Results and Fruit Size (June 2024).” https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Florida/Publications/Citrus/Citrus_Forecast/2023-24/cit0624.pdf

US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS) 2024b. Florida Citrus Statistics 2022–23. Accessed February 2024. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Florida/Publications/Citrus/Citrus_Statistics/2022-23/FCS2023.pdf

US Energy Information Administration (US-EIA). 2023. “Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Update.” https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/gasdiesel/

Wilson, H., K. M. Daane, J. J. Maccaro, R. S. Scheibner, K. E. Britt, and A. C. M. Gaudin. 2022. “Winter Cover Crops Reduce Spring Emergence and Egg Deposition of Overwintering Navel Orangeworm (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in Almonds.” Environmental Entomology 51 (4): 790–797. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvac051

Table 1. Partial budget on the costs of incorporating cover crops in orange production.

Table 2. Breakeven prices for ‘Valencia’ oranges for yield-quality quartile scenarios in Florida.

Table 3. Breakeven prices for non-‘Valencia’ oranges for yield-quality quartile scenarios in Florida.