To determine your wildfire risk, see UF/IFAS publication FOR71, “Landscaping in Florida with Fire in Mind,” at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/FR076; or Wildfire Risk Assessment Guide for Homeowners in the Southern U.S. at https://www.fdacs.gov/Forest-Wildfire/For-Communities/Firewise-USA/Wildfire-Hazard-Assessment).

Introduction

A major issue in the southern wildland-urban interface is the loss of homes to wildfire. This publication provides helpful landscaping information for land developers and homeowners who live in an area with a medium to high risk of wildfire. Although fire control agencies play an essential role in fire prevention and the protection of homes, individual homeowners, too, can take action to reduce the vulnerability of their homes to wildfire. This Extension publication explores the biological and structural characteristics of plants and their arrangement that have the greatest effect on flammability.

Creating an area of defensible space is crucial for protecting your home. Defensible space is an area of modified vegetation between natural areas (e.g., woodlands) and homes that breaks up the continuity of plants, within 100–300 feet of your home (Kays et al. 2020). Recommendations for defensible space suggest maintaining an area extending at least 30 feet outward from a house with low-flammability plants (referred to as firewise plants).

The movement of a wildfire is controlled primarily by the flammability of the plants present and how those plants are arranged, both vertically and horizontally. Selecting landscape plants based on their flammability can be challenging for homeowners and landscapers, as few existing plant guides rank plants by their flammability (see additional resources at the end of this publication). However, by considering several key plant characteristics that are known to influence flammability, homeowners can make informed decisions about which plants to select when creating an area of defensible space. Although selecting firewise plants reduces wildfire risk, most plants will burn if exposed to enough heat during drought conditions. Therefore, it is also important to modify existing plant vertical and horizontal arrangements to prevent the spread of wildfire.

What plant parts fuel the fire?

Both living and dead plant material will burn in a wildfire. When comparing the flammability of different plants, one should first consider the leaves and small branches, which are lightweight fuels that ignite easily and burn rapidly. Leaves from different plant species ignite and burn at different rates and intensities depending on their chemical and structural characteristics (Varner et al. 2015). These light fuels facilitate the spread of an advancing fire and carry the fire to heavier fuels, such as larger branches or even houses. The most important characteristics of light fuels that influence their flammability are explored below.

- The amount of water in a leaf. The moisture content of leaves varies significantly by season, local weather, and site conditions, such as air humidity and soil moisture. Differences also exist between plant species growing under the same conditions. Plants with thick, succulent leaves, such as cacti, aloe, and century plants, generally maintain high leaf moisture content, even during droughts, and thus have low flammability. Most living leaves are at least 50% water by weight. When exposed to heat or a flame, a leaf will not catch fire until most of its water is lost (primarily through evaporation). Therefore, leaves with the highest moisture content generally take the longest to ignite. Dead leaves are much drier than living leaves.

- The size and shape of leaves. Small, needle-like leaves, like those on pines and cedars, are generally more flammable than wider, flat leaves, such as those on maples, oaks, and hickories. The broad leaves of palms (called fronds) are exceptions to this rule, as they tend to have relatively high flammability. Leaf thickness is important because thick leaves have more plant tissue (and often more water) relative to the exposed surface area than thin leaves. When most thin leaves are exposed to fire, they ignite faster than thick leaves. When dead leaves drop from a tree, their shape can affect whether they get caught in shrubs below and thereby increase the flammability of those shrubs. For example, the fact that pine needles are bundled at the base increases their likelihood of getting caught on small branches as they fall. The flammability of shrubs and small trees increases as needles accumulate (Figure 1).

- The presence of oils, resins, waxes, or other chemicals in leaves or branches. Certain chemicals can increase the flammability of a plant. Leaves containing significant quantities of these chemicals will often emit an odor when crushed. When landscaping around homes in high wildfire-hazard areas, homeowners should limit the use of plants with high amounts of resins or oils in their leaves.

Credit: Raelene M. Crandall, UF/IFAS

Whole-Plant Flammability

The overall flammability of a plant depends on the relative flammability of its leaves and branches and how they are arranged. Shrubs and trees differ in their flammability based on several key characteristics. For example, flames might spread more quickly and easily through a shrub with dense layers of leaves and small branches than in a loosely branched shrub with few leaves.

- Branching patterns are important because they influence the distribution and number of leaves. Plants with open and loose branching and sparse leaves generally have low flammability. Examples of relatively open, loosely branching plants include ornamental plum trees, crape myrtle, and some azaleas.

- Deciduous vs. evergreen. Shrubs and trees that lose their leaves in the fall are deciduous, and those that retain living leaves throughout the year are called evergreen. Some common deciduous species in the southern United States include hickories, red and white oaks, and maples. Many common evergreen species have needle-like leaves, such as cedars, pines, and hemlocks; however, some broad-leaved plants are also evergreens, such as live oaks, hollies, and magnolias. Deciduous plants are usually less flammable than evergreens for several reasons. Living deciduous leaves tend to have a higher moisture content than evergreen leaves. In addition, deciduous plants do not readily ignite during winter because they have no leaves to burn. However, as described in the section on leaves, leaf size and shape are vital plant characteristics to consider, and leaves vary within each group (deciduous and evergreen). For example, magnolias and cedars are two evergreens with very different leaves. Their flammability varies, with the cedar being more flammable due to its small, needle-like leaves.

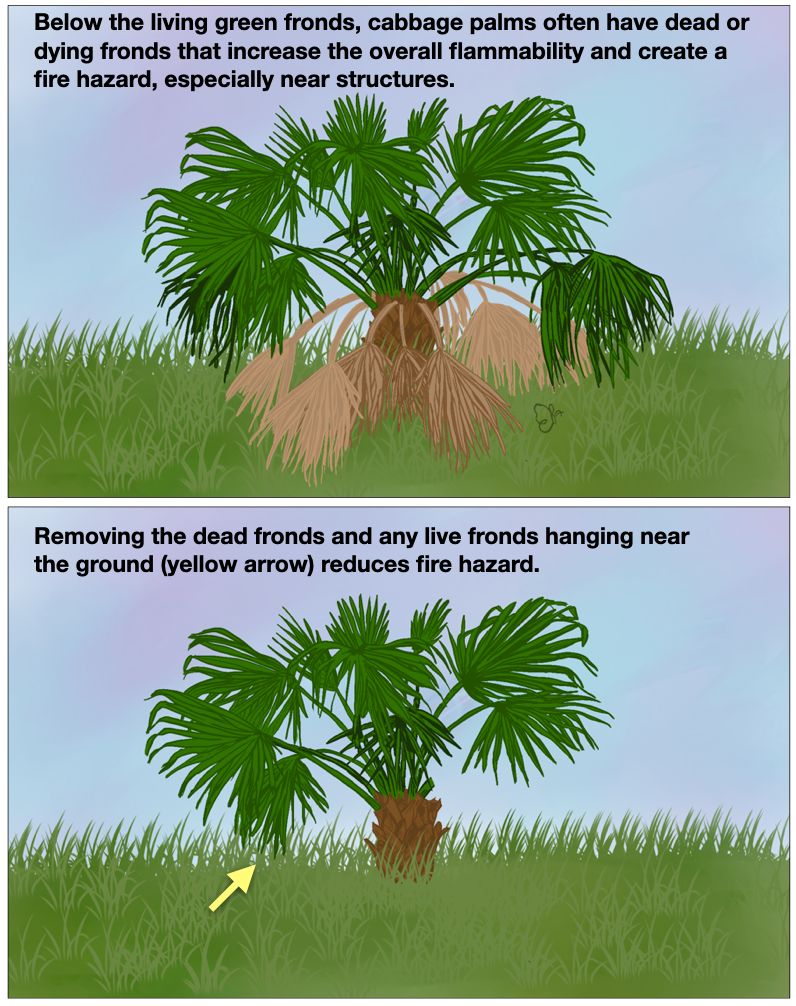

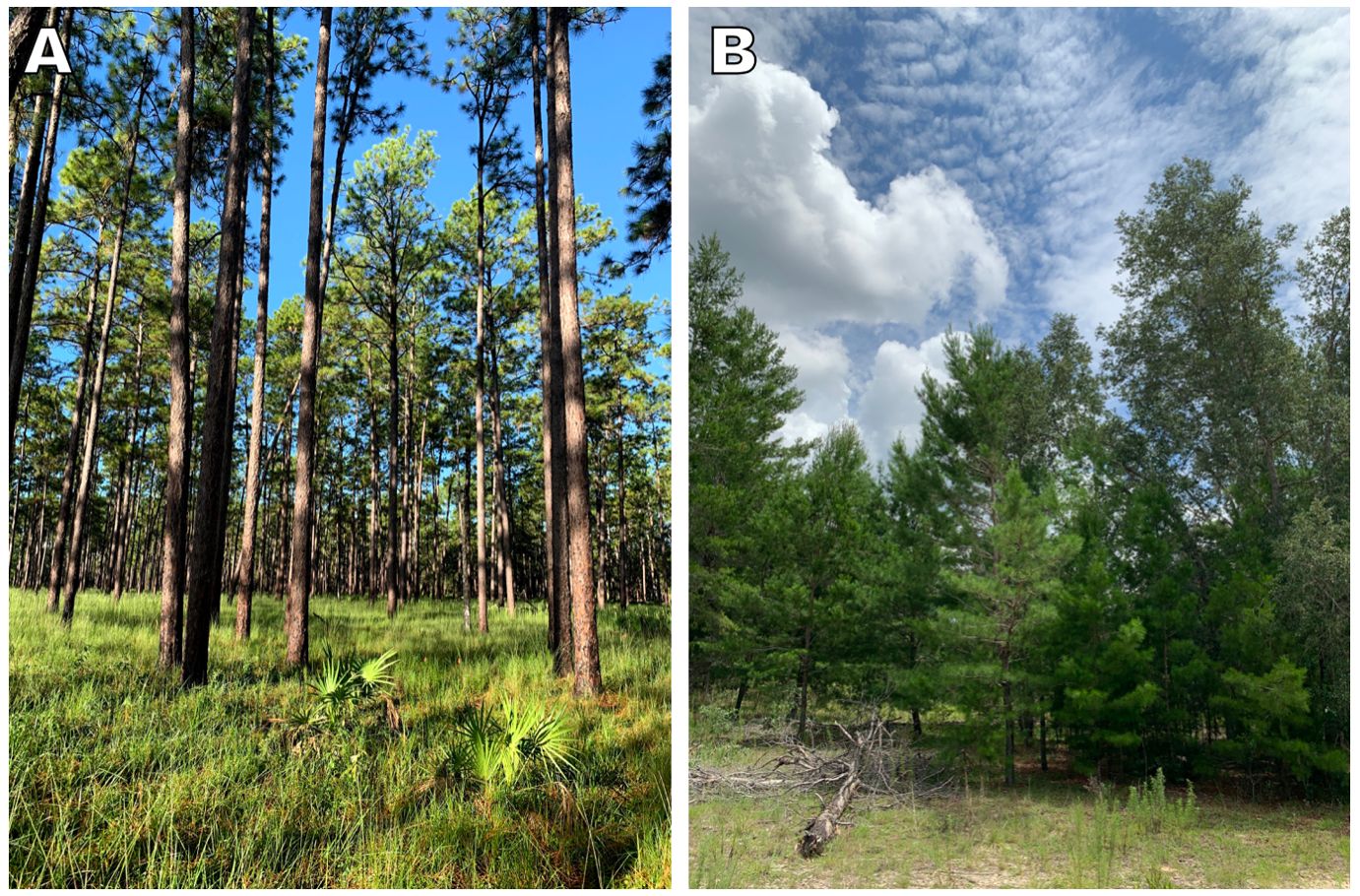

- The retention of dead leaves and branches can increase a plant's flammability because dead materials have low moisture content (Figure 2). As forest trees grow taller, their lower branches, which receive comparatively little sunlight, often die. However, the dead branches may remain attached for a while and increase the flammability of the entire tree. Some trees, called self-pruners, lose their lower, dead branches on their own as they grow. Self-pruning can lower a plant's flammability by creating greater vertical separation between the ground and the part of the tree containing leaves (Figure 3). Manual removal of branches up to 10 feet from the ground will reduce the fire hazard of mature trees that do not self-prune.

- Planting "the right plant in the right place" is important in landscaping, and it can influence plant flammability. When selecting landscape plants, consider their light, water, and soil requirements (http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/handbook/Right_Plant-Right_Place.pdf). If you are a homeowner, contact your county Extension agent or local nursery for assistance in selecting appropriate plants for the range of conditions in your yard. Plants that are not well suited for the local environment often require more resources, such as water and fertilizer, and may become stressed or diseased more easily. Unhealthy plants have a higher percentage of dead leaves and branches, significantly increasing their flammability.

Credit: Raelene M. Crandall, UF/IFAS

Credit: Raelene M. Crandall, UF/IFAS

Plant Arrangement within Landscaped Areas and Beyond

Like individual plants, the flammability of groups of landscape plants is influenced significantly by the vertical and horizontal arrangement of fuels. In many cases, the arrangement of groups of plants around a house is more important in determining wildfire hazards than the flammability of any individual plant. The general differences between broad categories of plants helps explain how plant arrangement influences the overall flammability of a landscape. Grasses and forbs, shrubs, and trees have different characteristics that influence ignition and fire spread during wildfires. Each plant type is discussed in the context of its arrangement above the ground because most advancing wildfires spread horizontally through fuels that lie on or within a few feet of the ground.

- Grasses and forbs are ground-level fuels. When they are dead or drought-stressed, they ignite rapidly and burn quickly if they have thin leaves and low moisture content. Living grass dries out more quickly than shrubs and trees during extended periods of dry weather when most wildfires occur. Forbs generally tend to burn more slowly and less intensely than grasses, all else equal, but this depends on their leaf thickness and water content.

- Shrubs have most of their leaves less than six feet from the ground and, therefore, are susceptible to ignition from fires spreading at ground level. In addition to having an abundance of leaves, many shrubs tend to grow in dense groups or thickets, which increases their flammability at the landscape scale. For example, gallberry is a native shrub of the southern United States that generally has sparse leaves and branches, characteristics that usually indicate low flammability; however, it occurs naturally in dense groups that are highly flammable. In fact, it is one of the most flammable naturally occurring groups of plants in the southern United States.

- Trees in the forest usually have most of their branches and leaves high above the ground; therefore, a ground-level fire will not easily ignite them unless plants of intermediate height or vines carry the flames from the ground to the treetops. This generalization does not always hold for isolated trees in open, bright areas, such as grasslands or lawns, which may have branches closer to the ground in response to the abundant light.

Plant height (or vertical arrangement) influences the potential for fire to spread from the ground to the treetops. In contrast, the proximity of a plant (or plant groups) to other plants (horizontal arrangement) influences the spread of fire across the landscape. In general, the flammability of a landscape increases with greater connectivity or continuity of fuels (primarily leaves and small branches), both vertically and horizontally. Therefore, the primary objective when landscaping for fire safety is:

- Vertical and horizontal separation. A firewise landscape has vertical and horizontal separation between all major fuel sources within the area of defensible space. Shrubs, vines, and small trees of intermediate height can act as ladders carrying the flames from the ground to the treetops; such plants are called ladder fuels. To maintain vertical separation, all ladder fuels should be cleared from this area, and the lower branches on trees should be pruned to 10 feet from the ground. Horizontally, groups of plants or landscape beds should be well-spaced and interrupted by nonflammable areas, such as decorative gravel and steppingstone pathways. Rather than turfgrass, which is very water-intensive, consider planting native plants that conserve water and support wildlife, such as perennial peanut and native sunshine mimosa (UF/IFAS 2009).

- Mulching can also be used in and around landscape beds. Because the flammability of different landscape mulches is still unclear, however, some precautions should be taken. Mulch should not be used in defensible space (within a minimum of 100 feet from a structure). Beyond this distance, use mulches composed of large chunks of wood and bark that may maintain moisture for a longer time and ignite relatively slowly when exposed to fires so that they present less of a fire hazard. Pine straw mulches, which dry out quickly, are highly flammable and should be avoided altogether in a firewise landscape. If mulching is desired within the defensible, space, shredded wood or bark could be cautiously used from 3 to 10 feet away from the structure as it is less flammable. Still, organic mulch (pine needles, pine bark, shredded wood, etc.) should not be used near wood or vinyl surfaces on buildings, as the heat released from the burning mulches may ignite or melt adjacent wood or vinyl (Zipperer et al. 2007). Also, be sure the pine bark and needles are not under shrubs that could then carry flames to the structure if ignited by the mulch. Both pine straw and pine bark can burn intensely, although pine straw burns quickly. Shredded cypress burns less intensely but because it burns slowly, it retains for a longer period the capacity to ignite surrounding plants (Zipperer et al. 2007).

Routine Maintenance is Essential!

Once plants are selected and the landscape design is created, routine maintenance is required to preserve firewise properties. Routine maintenance includes timely pruning, irrigation, and the removal of dead plant materials. Shrubs and trees should be pruned to maintain vertical and horizontal separation between leaves and branches. Water is important to maintaining healthy plants; homeowners who live in regions that experience periodic drought should avoid drought-sensitive plants in their landscaping. Dead plant materials removed during routine maintenance can be mulched or composted and used in the landscape to keep nutrients on-site (beyond defensible space). By avoiding plants that are fast-growing, particularly those that spread quickly, such as vines, homeowners can reduce the frequency of required maintenance practices.

Summary

The most important characteristics of firewise plants to consider are:

- High moisture content. The moisture content of leaves and branches is the most critical factor influencing the flammability of individual plants.

- Broad and thick leaves. Thin leaves or needles tend to dry out quickly and ignite easily.

- Low chemical content. Oils or other chemicals in the leaves and branches can increase flammability.

- Open and loose branching patterns. Fewer leaves slow fire spread.

- Deciduousness. Deciduous plants are generally less flammable than evergreens.

- Low amounts of dead materials. The accumulation of dead leaves and branches on plants can increase flammability.

The following southern landscape plants are examples of species that do not meet some of the preceding criteria and are usually highly flammable. These plants should be avoided in the area of defensible space around homes that are located in high wildfire-risk areas. Beyond the defensible space, individual plants of these species can be maintained, but they should be isolated from other plants and well-pruned to maintain vertical and horizontal separation. Key characteristics that contribute to their flammability are listed for each plant.

- Saw palmetto—an evergreen shrub, it accumulates dead branches, especially close to the ground. Both living and dead leaves are flammable.

- Juniper—an evergreen shrub with small, needle-like leaves. Resins in the leaves and branches increase its flammability. Juniper often retains dead branches if it is not pruned regularly.

- Mountain laurel—Young individuals have dense leaves and branches that hang close to the ground, although older individuals may develop a less flammable tree form with open branching.

To maintain a firewise landscape, conduct the routine maintenance practices described below within the area of defensible space.

- Maintain vertical and horizontal separation between groups or islands of landscape plants.

- Prune shrubs and trees periodically to reduce fuel volume, maintain healthier plants, and prevent the development of ladder fuels.

- Remove dead leaves and branches from standing vegetation and the ground.

- Remove dead annual plants.

- Water plants adequately to maintain healthy plants and prevent drought stress. If you live in an area where extended dry seasons or droughts are common, consider creating a low water-use landscape with drought-tolerant plants. (See publications on waterwise landscaping or xeriscaping: https://www.sjrwmd.com/water-conservation/waterwise-landscaping/.)

References

Bond, W., and B. van Wilgen. 1996. Fire and Plants. Chapman and Hall, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1499-5

Dennis, F. C. 1999. “Fire-Resistant Landscaping.” Colorado State University Cooperative Extension Publication 6.303.

Dennis, F. C. 1999. “Firewise Plant Materials.” Colorado State University Cooperative Extension Publication 6.305.

Gilmer, M. 1996. Landscaping in the I-zone. Pp. 194–203 in R. Slaughter (ed.), California's I-zone. State of California.

Kays, L., J. Fawcett. J. Query, H. Thompson-Welch, and R. Bardon. 2020. “Fire-Resistant Landscaping in North Carolina.” NC State Extension, NC. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/fire-resistant-landscaping-in-north-carolina

Monroe, M. C., J. M. Fill, R. M. Crandall, and A. J. Long. 2022. “Landscaping in Florida with Fire in Mind.” EDIS 2022. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/FR076

UF/IFAS. 2009. “Turf Alternatives.” https://wec.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/gc/harmony/landscaping/turfalternatives.htm

Varner, J. M., J. M. Kane, E. M. Banwell, and J. K. Kreye. 2015. “Flammability of Litter from Southeastern Trees: A Preliminary Assessment.” Pages 183–187 in Proceedings of the 17th Biennial Southern Silvicultural Research Conference, edited by A. G. Holley, K. F. Connor, and J. D. Haywood. e-Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-203. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 551 p.

Zipperer, W., A. Long, B. Hinton, A. Maranghides, and W. Mell, W. 2007. “Mulch Flammability.” Pages 192–195 in Proceedings of Emerging Issues Along Urban-Rural Interfaces II: Linking Land-Use Science and Society, edited by D. N. Laband. Auburn University.

Additional Guides to the Flammability of Plant Species and Mulches

Kays, L., J. Fawcett. J. Query, H. Thompson-Welch, and R. Bardon. 2020. “Fire-Resistant Landscaping in North Carolina.” NC State Extension, NC. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/fire-resistant-landscaping-in-north-carolina

Southern Forest Research Station’s Quick Guide to Flammable Shrubs. https://urbanforestrysouth.org/products/fact-sheets/fire-in-the-interface-fact-sheets/quick-guide-to-firewise-shrubs/index_html

Long, A. J., A. Behm, W. C. Zipperer, A. Hermansen, A. Maranghides, and W. Mell. 2006. “Quantifying and Ranking the Flammability of Ornamental Shrubs in the Southern United States.” Pages 13–17 in 2006 Fire Ecology and Management Congress Proceedings. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/ja/ja_long004.pdf

South Carolina Forestry Commission “Fire Smart” plant list for South Carolina. https://www.state.sc.us/forest/scplants.pdf

University of Florida’s firewise plant flammability key. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR151

USDA Forest Service “Flammability of Selected Landscape Mulches.” https://changingroles.interfacesouth.org/videos/mulch-flammability-videos

Other Publications in the Fire in the Wildland-Urban Interface Series

Circular 1431: Fire in the Wildland-Urban Interface: Considering Fire in Florida's Ecosystems.

Circular 1432: Fire in the Wildland-Urban Interface: Understanding Fire Behavior.

Circular 151: Fire in the Wildland-Urban Interface: Preparing a Firewise Plant List for WUI Residents