Abstract

Although millions of people recreate in parks, forests, and other conservation areas in the United States every year, research shows that large groups of people do not take advantage of natural areas for the numerous benefits nature-based recreation areas provide (Jackson 2000). Based on research conducted in Hillsborough County, Florida, and similar studies, this paper addresses people's perceived constraints to nature-based recreation and identifies strategies to improve the opportunities natural areas can provide a diverse, urban public. Results that examined the constraints for specific types of people showed that non-white respondents cited cost, distance, and lack of information as constraints, women were more likely to address safety concerns as constraints, and respondents in lower income groups were more likely to say they simply disliked participating in outdoor recreation. In all cases, a mix of managing the recreation areas and developing effective communicative strategies will broaden access to the valuable recreation benefits available in natural areas for a more diverse group of people.

Introduction

Outdoor recreation is more than just fun and games. Enjoying a picnic in a natural area, away from the clamor of urban life, can help bring friends and family members closer together. Canoeing down a winding river can help the paddler improve overall physical health and his or her canoeing skills. Hiking through the woods and finding unique wildlife can instill a sense of wonder and respect for the natural world. Spending time in nature not only allows people to make lifelong memories but can also improve social, emotional, physical, intellectual, and spiritual health (Breitenstein & Ewert 1990; Hartig et al. 2014).

With so many possible benefits of outdoor recreation, it makes sense that many different types of professionals would want to encourage participation. Specifically, public land management and parks and recreation agencies manage the attractions that most Americans use for outdoor recreation; therefore, providing quality recreation opportunities to the public is a major component of their job. However, other professionals can use outdoor recreation to achieve their goals: teachers might want to encourage their students to experience the natural world to better learn science, medical professionals might want to encourage patients to get exercise or relieve stress outdoors, and employers may want to encourage their employees to get outside and recreate to improve team building and workplace efficiency. Everyone can benefit from outdoor recreation, and anyone can have the skills to encourage participation. But not everyone takes advantage of nature, and that is the focus of this paper.

Purpose

Many people who otherwise might participate in outdoor recreation perceive barriers or constraints that prevent them from going into nature. Constraints are defined by Jackson (2000, p. 62) as "factors that are assumed by researchers and/or perceived or experienced by individuals to limit the formation of leisure preferences and/or inhibit or prohibit participation and enjoyment in leisure." Much research has explored recreation constraints and discovered some general patterns. For example, researchers at Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest in Washington found visitors perceived structural constraints, such as lack of time due to work or school and lack of information, as obstacles to outdoor recreation. Other studies have shown people perceive constraints based on their perceptions or beliefs of an area (i.e., intra/interpersonal constraints). For example, Scott and Jackson (1996) found people might feel unsafe in certain environments, and other research has shown that certain ethnic or racial groups might not participate as much as whites due to historical discrimination (Krymkowski et al 2014; Shores, Scott, and Floyd 2007).

It can be challenging to encourage people to get outside when so many known and unknown barriers exist. The goal of this article is to discuss the major barriers people perceive to outdoor recreation and provide suggestions to encourage participation in outdoor recreation for natural areas within and bordering urban areas in Florida. Discussion and suggestions are based on research conducted in Hillsborough County, Florida. Floridians have a unique relationship with nature due to the state's unique subtropical environment and racially diverse urban population. However, there is a lack of research examining recreation constraints in the state. Although the study described here cannot be generalizable to larger populations, it highlights consistent findings with other recreation-constraint research conducted throughout the United States, but it also will point out unique findings for the Florida residents examined in this study.

Methods

In 2016, researchers at UF/IFAS partnered with the Hillsborough County Environmental Lands Management (ELM) Department to answer the following questions for Hillsborough County residents who were not currently visiting ELM lands:

- How big a priority is nature-based recreation in relation to other ways to spend leisure time?

- Identify and describe the important constraints to participating in recreation in natural areas?

- How do different types of people, based on gender, ethnicity, and income, perceive different constraints to nature-based recreation?

- What can managers do to encourage more outdoor recreation?

The Hillsborough County ELM Department is similar to many county land management agencies in that it must manage for the dual purpose of natural resource protection and public access recreation. Specifically, the department manages more than 61,000 acres of environmentally sensitive lands. Different areas have different management objectives. There are conservation areas with limited recreation access, nature preserves and trails that only allow for non-motorized recreation access, and regional parks with amenities like bathrooms, paved trails, picnic benches, and boat ramps, which host thousands of visitors a year.

Hillsborough County is in central-west Florida and includes the cities of Tampa, Temple Terrace, and Plant City (Figures 1 and 2). According to the 2010 US Census, 51% of residents are white alone, 27% are Hispanic or Latino, 17.7% are black, 4.1% are Asian, 0.5% are American Indian or Alaskan Native, 0.1% are Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 2.6% are two or more races. Also, 51.3% of the population are female, 87.5% are high school graduates, 30.6% have at least a bachelor's degree, and the median household income is $50,579.

Credit: Map showing relative location of Hillsborough County.

Researchers administered questionnaires verbally to 119 individuals selected randomly at laundromats, a downtown city park, a shopping plaza, public libraries, and malls in Tampa and the suburb of Brandon. The locations were chosen with the help of the ELM Department to reach a diverse population that included people who might not go to nature parks.

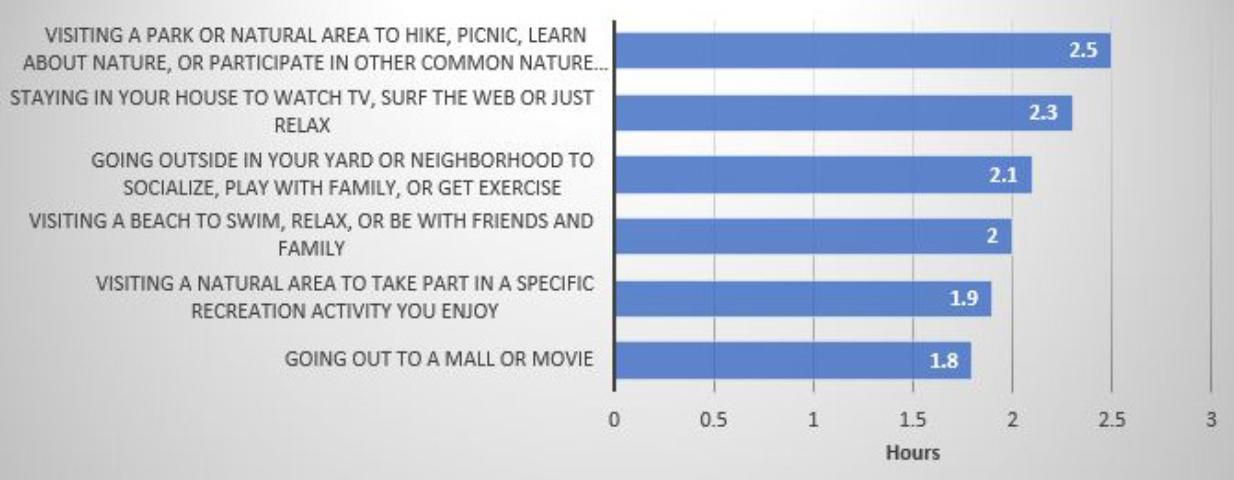

Nature-Based Recreation is an Option among Many

Study results showed that the Hillsborough County residents who participated in this study do value nature-based recreation (Figure 3). When asked how much time they would spend doing a variety of leisure activities if they had 12 hours of free time, respondents said they would spend the most time "visiting a park or natural area to hike, picnic, learn about nature, or participate in other common nature activities." In fact, participants said they would hypothetically spend an average of 2.5 hours participating in nature-based recreation, which slightly beat out the next most popular leisure activity, "staying in your house to watch TV, surf the web, or just relax," which received an average response of 2.3 hours. The least popular option was "going out to a mall or movie," with an average response of 1.8 hours.

Clearly, answering a question about performing a behavior is different than actually performing that behavior. However, this finding shows Hillsborough residents value going outside to participate in recreation. Other studies show that families and children are participating in outdoor recreation, but they value other recreation activities, and these activities are often prioritized above outdoor recreation. For example, Larson, Green, and Cordell (2011) found that children preferred listening to music, making art, reading, watching television or DVDs, playing video games, and using electronic media like the Internet or texting more than participating in outdoor recreation. Therefore, it is still necessary to understand what they believe is constraining their ability to participate in recreation and to identify ways to make outdoor recreation a preferable leisure activity.

The remainder of this paper uses the results of the Hillsborough County study to highlight key constraints facing residents in a major Florida urban area and to highlight how recreation proponents can motivate different types of Florida residents who feel constrained to participate in nature-based recreation.

Constraints That Stop People from Visiting Nature

When asked about why they do not participate in outdoor recreation, people believe they are simply too busy, but other constraints also play a role (Table 1). Although no constraint received a score of four or higher on the five-point scale (where 1 = "not at all important" and 5 = "very important"), the top five highest-ranked constraints were considered to be "somewhat important."

The top five highest-ranked constraints all had to do with lack of time. This is consistent with past studies of constraints and reaffirms that Americans are busy people, and other activities (e.g., family and employment) are getting in the way of recreation (Shores, Scott, and Floyd 2007; Scott and Jackson 1996). The fourth-ranked item indicates people just do not know about Hillsborough County parks and programs. Finally, the fifth-highest-ranked constraint shows that people are going to other places for recreation. Participants in this study do not appear to be scared of nature. "Fear of the outdoors" received the lowest score of all the constraints.

Although lack of time is a constraint many people can easily identify with, what's stopping them from participating in nature-based recreation is likely more complicated than simply lack of time. Public land management agencies do not have much control over people's perception of lack of time, but they might be able to highlight the quality experiences people would attain if attending their areas to help make nature-based recreation seem more valuable, and, hence, a greater priority for potential participants. For instance, when asked what would encourage them to take part in nature-based recreation, most respondents said they would visit parks more if they had "access to more information and there were more opportunities to view wildlife." If natural areas were perceived to provide greater experiences for a visitor, like seeing unique wildlife, residents might be more likely to prioritize nature-based recreation over other activities.

Effective advertising and accessible information are both crucial to attracting more visitors who might not realize how many opportunities are offered by nature-based recreation. If people who do not participate can get more information about public natural areas, such as where to find them or what facilities are offered at various locations (e.g., wildlife-viewing platforms), they might be more inclined to see outdoor recreation as a valuable way to spend time. Of course, effective messaging would be different for different types of people; therefore, specific groups of people will be discussed below.

Increasing Ethnic and Racial Diversity

In 2017, a report by the Outdoor Foundation showed that about 73% of outdoor recreation participants were Caucasian, 10% were Hispanic, 9% were African American, 6% were Asian, and 2% were other. The lower proportions of minority participation indicate that specific groups of people are not taking advantage of the various opportunities afforded by nature-based recreation. In the Hillsborough County study, non-whites listed tangible obstacles to participating in recreation: cost, distance, and information. These are difficult barriers to overcome, and it would require nature-based recreation suppliers to work with other agencies and policy makers to alleviate these problems. Possible strategies to lessen these constraints include:

- Cost: If cost is too high for some people, managers could consider making changes to the fees and offering a certain number of free days throughout each month. Offering passes or discounts to neighboring communities might also reduce the cost to local residents.

- Distance: Parks being too far away might be a bigger, structural issue that land managers and general citizens cannot control, but land allocation priorities might be adjusted to include proximity to diverse, non-white communities.

- Information: Better communication with non-white populations is a clear implication of this research and related studies. Instead of keeping information related to the opportunities natural areas provide within the same circles via Facebook, email announcements, and so on, both land managers and existing users could make a bigger effort to spread information to diverse groups using alternative media (e.g., Spanish radio stations).

Increasing Gender Diversity

Spreading information effectively is also a useful tool for increasing gender diversity, but the messaging might be different. In the Hillsborough County study, women tended to rate safety concerns as a reason for not participating in outdoor recreation more than men. Managers should specifically address potential safety issues when promoting their natural areas. Also, managers should understand what people are specifically concerned about when it comes to safety. For example, safety concerns could address crime, which could be minimized through law enforcement and other management strategies. Managers might take a different approach with general concerns related to nature (e.g., wild animals), which might require education that addresses the fear but explains the fear might not be justified (e.g., snakes are not lying in wait for children along the trail). They could also clearly communicate appropriate recreation behavior, which would minimize risk to both the visitor and the wildlife (e.g., "stay on the trail").

Increasing Socioeconomic Diversity

Again in the 2017 Outdoor Foundation Participation Report, it was shown that 70% of outdoor recreation participants reported an annual household income of greater than $50,000, and 32% of participants reported an annual household income of greater than $100,000. Across the United States, lower income populations are proportionally not benefitting from nature-based recreation's benefits (Larson et al. 2011). In the Hillsborough County study, results showed that respondents in lower income groups were more likely to say they disliked participating in outdoor recreation than higher income respondents. Also, women were more likely to rank this constraint higher than men.

The finding that people just "dislike" participating in recreation does not point to a clear implication, except to better understand what people might want from a natural area. Research has long examined the desires and motivations of typical users (e.g., white, middle- to upper-income visitors), but what nature can provide to lower income residents must still be understood and might often be site specific to the community. The Hillsborough study did ask participants what facilities and services would motivate them to participate in outdoor recreation. Almost 80% of respondents said they would participate more in outdoor recreation if they were provided more information about existing parks and park programs. Of course, this requires managers to communicate effective and attractive messages to residents. The key is identifying what these messages might be and how to market them to various audiences. Some parks could highlight their unique and natural elements, which all visitors could experience. For example, water-based recreation is consistently listed as a desirable attraction, especially in Florida, so parks with swimming opportunities should highlight that activity.

Another finding of this study showed that 86% of respondents said they would participate more if there were more amenities to allow them to view wildlife. Wildlife viewing is a popular activity at many parks and conservation areas, but it is difficult to guarantee wildlife observation. However, conservation areas throughout the United States do their best to provide wildlife observation opportunities when they are possible. Providing observation areas and interpretive materials near areas that wildlife are likely to visit (e.g., lakes or prairies) is often a low-cost method to provide wildlife observation opportunities. Of course, the public and visitors must know about these opportunities. Simply providing a wide spot in the road for parking near a likely wildlife observation area will not provide the opportunity visitors seek unless they know wildlife can be found in the area. Those observation areas must therefore be clearly identified and promoted. Information on websites about the areas, maps to the areas, and signs at each specific observation area should clearly highlight the attraction.

Conclusion

This paper used a study conducted in Hillsborough County as an example of how urban residents feel constrained to participate in nature-based recreation. This study did have a small sample size, and future research should work to increase the number of study respondents to adequately infer to larger populations. However, similar results related to recreation constraints have been found in other recreation studies by researchers such as Green et al. (2012), Metcalf et al. (2013), Scott and Jackson (1996), among others, so the results and implications discussed here can be applied to land management agencies and outdoor enthusiasts throughout Florida.

A key finding of this study is the need to communicate adequately with the public. Not only did study respondents identify "lack of information" as one of the higher ranked constraints to nature-based recreation, communicating with the public can alleviate many of the other constraints different types of respondents believe are important. For example, information related to safety (e.g., describing appropriate behaviors to ensure safety) can be relayed through park websites and in signs throughout the area. Also, promoting opportunities to view wildlife both outside the park and within the park will reduce the constraint that people just find nature uninteresting. By effectively communicating specific types of information, managers can raise awareness of the potentially valuable outdoor recreation opportunities in these natural areas in diverse groups of people.

Citations

Breitenstein, D., and A. Ewert. 1990. "Health benefits of outdoor recreation: Implications for health education" Health Education 21 (1): 16–21.

Green, G. T., J. M. Bowker, X. Wang, H. K. Cordell, and C. Y. Johnson. 2012. A national study of constraints to participation in outdoor recreational activities. In H. K. Cordell (Ed.), Outdoor recreation trends and futures (pp. 70–74). Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station.

Hartig, T., R. Mitchell, S. de Vries, and H. Frumkin. 2014. "Nature and health." Annual Review of Public Health 35 207–228. https://doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443.

Jackson, E. L. 2001. "Will research on leisure constraints still be relevant in the Twenty-first Century?" Journal of Leisure Research 32 (1): 62–68.

Krymkowski, D. H., R. E. Manning, and W. A. Valliere. 2014. "Race, ethnicity, and visitation to national parks in the United States: Tests of the marginality, discrimination, and subculture hypotheses with national-level survey data." Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism,7-8: 35–43.

Larson, L. R., G. T. Green, and H. K. Cordell. 2011. "Children's time outdoors: Results and implications of the National Kids Survey." Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 29 (2): 1–20.

Metcalf, E. C. R. Burns, and A. Graefe. 2013. "Understanding non-traditional forest recreation: The role of constraints and negotiation strategies among racial and ethnic minorities." Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 1–2: 29–39.

The Outdoor Foundation. 2017. Outdoor Participation Report 2017. The Outdoor Foundation, Washington, D.C. 43pp.

Shores, K. A., D. Scott, and M. F. Floyd. 2007. "Constraints to outdoor recreation: A multiple hierarchy stratification perspective." Leisure Sciences 29: 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400701257948.

Scott, D., and E. L. Jackson. 1996. "Factors that limit and strategies that might encourage people's use of public parks." Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 14 (1): 1–17.

Whiting, J. W., L. R. Larson, G. T. Green, and C. Kralowec. 2017. "Outdoor recreation motivation and site preferences across diverse racial/ethnic groups: A case study of Georgia state parks." Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 18 10–21. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2017.02.001