This publication provides a practical guide for homeowners and professional arborists to maintain dead wood habitat on their property or their clients’ property. It outlines the environmental and financial benefits of keeping dead wood, the different types of habitat one can manage, and strategies for mitigating the risk associated with dead wood.

Introduction

A healthy, living tree is a fortress. Its defenses—in the form of resin and chemicals in the bark—prevent insects and pathogens from invading the tree’s bark and wood. However, once that tree dies, its resources become less defended against the bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals that use decaying wood. In Florida, standing dead trees, called “snags” or “wildlife trees,” provide critical habitat for countless insects, reptiles, and mammals to forage, hunt, and reproduce. In fact, 25 of Florida’s bird species require dead branches or rotting cavities for their nesting sites, including the pileated woodpecker and white-breasted nuthatch (Schaefer 1990). Dead trees bring forth new life. A forest with dead trees is a forest with biodiversity.

A Growing Trend

Around the world, there is a growing movement to preserve dead wood habitats in urban landscapes. City planners and foresters increasingly recognize the important role that dead wood plays in the environment, and new regulations and practices support dead wood’s ecosystem services in cities. In the European Union, for example, some member states require forest managers to conserve “optimal levels of deadwood” in their landscapes (EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020, 2011, Target 3, Action 12). In the United States, many urban communities place logs in parks and gardens as habitat for native pollinators and fungi. The practice of preserving dead wood is transitioning from a fringe approach to a mainstream strategy for promoting urban biodiversity.

When making decisions about dead trees in your yard, keep in mind that you do not always have to completely remove trees and grind up their stumps. You can opt to cut off the dangerous top or branches of your snag and leave a standing portion of the tree’s main stem. These human-made structures—commonly called “wildlife poles” or “woodpecker poles”—also promote backyard biodiversity, from pileated woodpeckers and bess beetles to five-lined skinks and flying squirrels. As Florida’s natural forests are converted to other land uses, wildlife poles in urban areas can serve as much-needed refuges for these organisms.

Credit: Ben Schwartz, UF/IFAS

Types of Urban Dead Wood Habitat

Not all homes, yards, or urban greenspaces can accommodate large standing snags or wildlife poles. Fortunately, there are several other dead wood structures that you can preserve. Dead wood on the ground is also important for the ecosystem. Wood and brush piles provide habitat for a remarkable array of creatures, from box turtles to the harmless black racer snakes. Many animals seek such shelter to overwinter. Besides large animals, logs and stumps can support an amazing array of colorful fungi and insects. Furthermore, your living trees may already have dead wood habitat within them. For instance, hollow cavities can harbor flying squirrels and nesting birds, while gaps and slits under injured bark can shelter lizards, frogs, and bats. Dead treetops and branches serve as ideal perches for songbirds and strategic vantage points for raptors and owls (Ober and Minogue 2007). Whether you maintain an entire snag or just a small brush pile, stewarding some form of dead wood can be a gratifying way to observe and conserve local wildlife.

Common Varieties of Dead Wood:

- snags and wildlife trees (natural, standing dead trees)

- “wildlife poles” and “woodpecker poles” (the main stem, trunk, or high stump left after cutting off the top of a snag or dying tree)

- dead branches

- cavities and slits

- logs

- stumps

- brush piles

Credit: Jiri Hulcr, UF/IFAS

Ecological Benefits

The primary benefit of retaining dead wood is that it makes your property more hospitable to wildlife. A snag or wildlife tree is an evolving object. It develops over time, providing different habitats and food to a succession of organisms. Importantly, with age and decay, its value to organisms increases. Maintaining such biodiversity hotspots in your yard will provide you with a deeper connection to your property and the opportunity to observe life that typical urban landscapes cannot support.

Dead wood also benefits your soil. A snag, stump, or log helps retain soil integrity and minimizes erosion on slopes. Over time, wood disintegrates into small debris, or humus. This returns organic material and nutrients to the soil, ultimately benefiting neighboring plants and supporting the next generation of trees.

Saving Money

Retaining dead wood on your property can also save you money. As a homeowner, you may hire a professional arborist to remove your dead trees. Paying for an entire tree removal plus the stump grinding can be quite expensive. However, if you have your arborist create a wildlife pole and leave a high stump in the landscape, they will have fewer cuts to make and less wood to haul, and cleaning up will be faster. The arborist will typically charge you less for this service. In this way, preserving habitat is less expensive than removing it.

As an arborist, turning dead or declining trees into wildlife trees reduces the amount of wood you must haul, saving you money on fuel and waste disposal fees. Additionally, leaving habitat can create lasting client relationships. Some homeowners want their yards to support wildlife. By providing a conservation-focused option, you can gain repeat customers and expand your clientele into a community of wildlife enthusiasts.

Risk and Practical Solutions Around Dead Wood

When trees die, they lose the ability to maintain their structural activity through growth and defend against active decay. It is only a matter of time before a snag or wildlife tree fails or breaks apart. A good-sized stump can be a living part of your space for years, slowly changing and nurturing different species each year as it disintegrates. That said, standing dead trees can be safely incorporated into your landscape if they are in remote areas or away from structures, vehicles, and foot-traffic. The most important factor in determining tree risk is the presence of potential targets that could be damaged or injured when the tree falls. Dead trees can pose low risk as long as they are located in remote or protected corners of your property where they will not impact people, property, or utilities. An arborist certified by the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) for Tree Risk Assessment Qualification (TRAQ) can help you identify which snags minimize risk while still maximizing the benefits to wildlife. If you are a homeowner or an arborist, or if you are simply interested in local conservation, here are some considerations you can take when managing dead wood on your property.

For the Homeowner

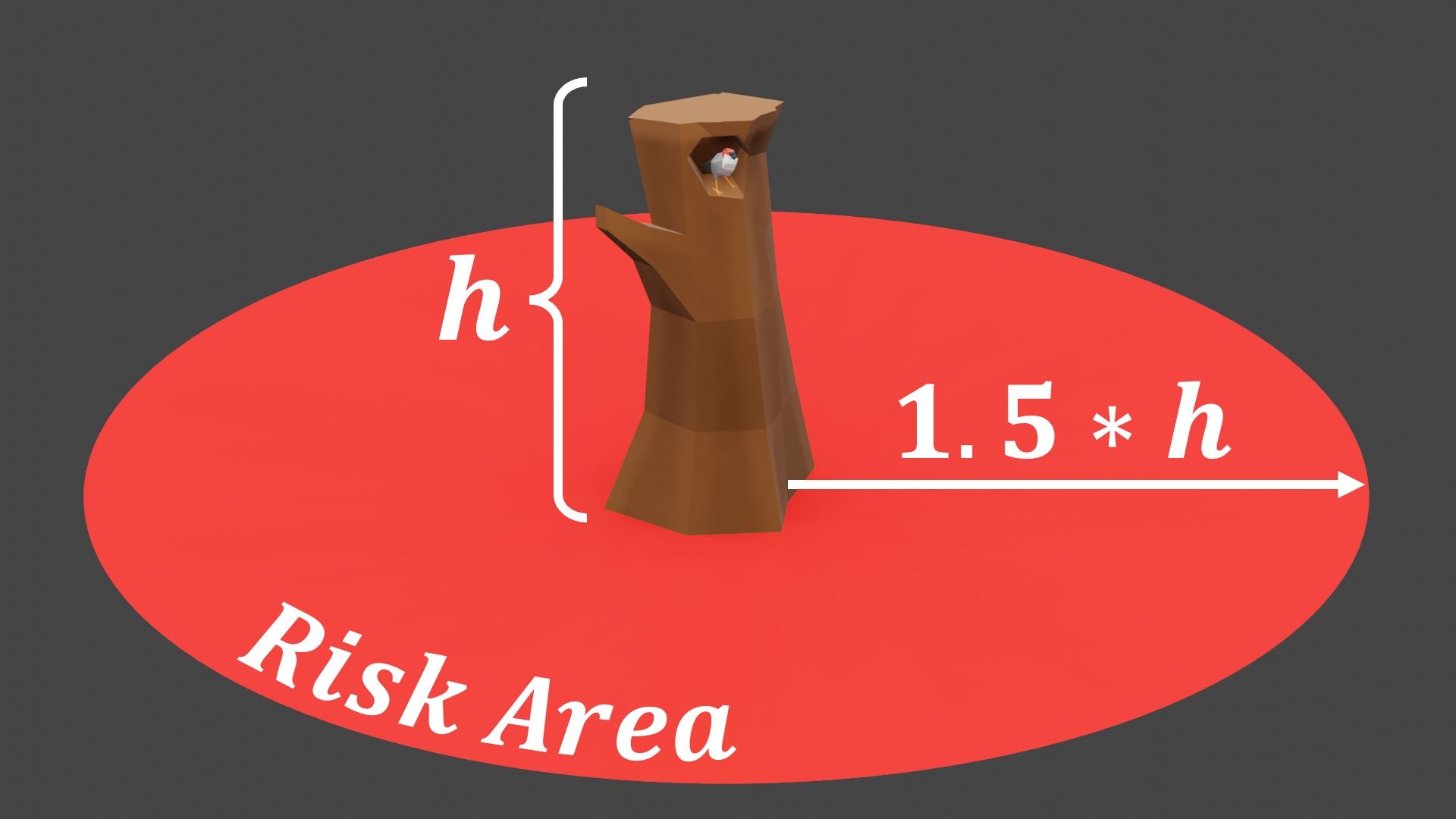

Your primary concern as a homeowner is safety. The goal is to minimize the risk of your dead tree or wildlife pole falling on someone or someone’s property. When an arborist comes to your home, they will look for potential targets by estimating the strike area around your trees. In calculating the strike area, they may use the tree as a center point and mark out a circle with a radius as large as 1.5 times the tree's height. The extra space accounts for the risk of dead wood shattering and scattering on impact.

Note any “targets of value” in the circle that would be damaged or destroyed if the tree were to fall. If there are targets, can you safely move them? For example, a swing set or table might be relocated. If the target is more permanent—say a utility line or a house—have your arborist trim down the tree to a height that shrinks the circle enough to remove the targets from the risk area. Don’t feel bad about shortening your wildlife poles. Maintaining even a short pole or stump is still ecologically better than maintaining no dead wood at all!

You must also consider the “occupancy rate” of your tree’s risk area. Do people walk near or under your dead tree? If there is a footpath or roadway, how often is it used? A busy driveway will carry increased risk relative to a seldom traveled backwoods trail. Do not hesitate to remove your dead tree if the area around it is busy. Remember that safety is the number one priority.

To recap:

- If your dead tree is not in a risky area, then leave it be and let it decay undisturbed.

- If it poses a risk to people or structures, then work from these three options:

- If possible, move targets of value out of the strike area.

- If moving targets is not feasible, try cutting the wildlife pole to a safe height that poses reduced risk to targets or occupants.

- If the tree must be removed, consider leaving its wood as a log or pile on the ground. Whether it’s standing or not, dead wood is an important habitat.

In a Homeowners Association?

While many homeowners treasure a snag or log’s natural look and feel, some Homeowners Associations (HOA) may consider dead trees unsightly. Ask about or look up your HOA’s rules concerning dead wood. If the association is open to you having dead wood, great! If it is not, then consider talking with neighbors about the benefits of dead wood and how it can be managed safely. Perhaps over time, you can gain enough local support to change the HOA rules. One way to manage the public perception of your dead wood habitat is by making it feel intentional. For example, if you have a large stump, consider placing a flowerpot on it to designate it as part of your landscaping. If you have a wildlife pole, hang a sign that identifies your snag as something like “wildlife home” or “woodpecker habitat.” You may be amazed by how small decorations can transform neighborhood perceptions of your dead wood.

Some people equate the presence of dead wood with a decrease in property value. However, by preserving dead wood we are increasing the ecological and aesthetic value of a property, which is increasingly appreciated in many communities. It is already common for people to bring songbirds and hummingbirds to their yards with bird baths and feeders. How are dead logs and woodpecker poles different? After all, they are natural birdhouses! Properly maintained dead trees frequently become conversation pieces that can facilitate neighborhood and HOA education. They add beauty to our yards and value to our lives.

Credit: Jiri Hulcr, UF/IFAS

For the Arborist

Homeowners and courts of law will use your reputable testimony when they make their decisions. Your clients rely on your expertise to strike a balance between the liability concerns and environmental benefits of the dead wood on their properties. Therefore, it is important that you stay current on your education and certifications. If you have not done so already, take the ISA Tree Risk Assessment Qualification (TRAQ) course and seek out other pertinent continuing education opportunities. Know how to diagnose trees according to the industry codes for the likelihood of tree failure and the consequences of an impact (Ellison 2017). Keep in mind that tree health and tree structure can be separate traits. Healthy trees may have poor structure and pose risk, while dead trees may have strong structure and pose less risk. Trimming the crowns of “weedy” oaks like laurel oaks or water oaks decreases their competition with the more valuable live oaks in the canopy layer and makes them less dangerous (branches of these fast-growing oaks often break). Their half-dead-half-live snags then become true biodiversity hotspots in the lower parts of the canopy. In terms of ecological value, there are no specific guidelines yet, but two rules of thumb apply: 1) native trees are always more valuable to the local fauna and fungi than non-native trees, even after their deaths; and 2) the harder the wood, the longer it will serve as a wildlife refuge. Weigh all the factors and describe the risks to the homeowner as accurately as possible. Give your opinion when appropriate, but ultimately, the client decides the amount of risk they can or cannot tolerate.

Other Concerns

In Florida, wildfire is a concern in the urban-wildland interface. As you create a fire-buffer of defensible space around your house, it’s advisable to remove lighter fuels that ignite easily, such as grasses, needles, and twigs. Experts refer to these as “one-hour” fuels—material that can dry out to surrounding humidity in one hour or less. Fortunately, most large dead wood structures are “one-hundred hour” or more fuels. They do not dry out as quickly and do not pose an immediate risk of igniting from sparks alone (Davies and McMichael 2005).

Another concern often expressed by homeowners about dead wood is the fear of termites occupying your snag and then jumping over to your home. Fortunately, this is not how most termites spread. Most termite species in Florida are subterranean—they access new sources of wood through dead roots. Therefore, termite prevention should primarily focus on the soil around your house (Su and Scheffrahn 2020). Another conduit for termite infestation could be through old wood that is directly touching your structure, such as an abandoned firewood stack. Wood stacked against a house is not a suitable wildlife habitat, and we do not recommend it. Ensuring ample space of at least three feet between your house and your dead wood habitat will give you the space to visually observe the base of your structure and help alleviate the risk of termite damage. If you are worried about subterranean termites, or live in a high-risk area, you can use chitin synthesis inhibitor (CSI) baits placed around your structure for added prevention against these termites.

Conclusion

Keeping dead wood in your yard is a great opportunity to support urban wildlife and connect with the natural world. Homeowners and arborists can work together to minimize the risks associated with dead trees while maximizing the ecological, financial, and aesthetic benefits that come with conserving dead wood. Now, when your next tree dies, you will be prepared. Death is just the beginning. What comes next is up to you.

Additional Information

If you want more information on tree liability and regulations, see the Handbook of Florida Fence and Property Law: Trees and Landowner Responsibility (https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fe962-2014).

Looking for additional ways to increase your yard’s biodiversity? Consult Landscaping Backyards for Wildlife: Top Ten Tips for Success (doi.org/10.32473/edis-uw175-2003).

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Dr. Thomas Chouvenc, an expert on termites, for information used in this publication.

References

Davies, M. A., and C. McMichael. 2005. “Evaluation of Instruments Used to Measure Fuel Moisture.” United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/t-d/pubs/pdfpubs/pdf05512347/pdf05512347dpi72.pdf

Ober, H. K., and P. J. Minogue. 2007. “Dead Wood: Key to Enhancing Wildlife Diversity in Forests: WEC238/UW277, 7/2007.” EDIS 2007 (20). Gainesville, Florida. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-uw277-2007

Our life insurance, our natural capital: An EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. 2011. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0244

Dunster, J. A. 2017. Tree Risk Assessment Manual. International Society of Arboriculture. https://wwv.isa-arbor.com/store/product/442/

Ellison, M. J. 2017. Quantified tree risk assessment practice note. Version, 5, p.V5.

Schaefer, J. 1990. Helping Cavity-Nesters in Florida. SSWIS901. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW058

Su, N.-Y., and R. Scheffrahn. 2020. "Formosan Subterranean Termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki (Insecta: Blattodea: Rhinotermitidae): EENY121/IN278, Rev. 5/2000”. EDIS 2002 (8). Gainesville, Florida. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-in278-2000