Introduction

The black mangrove, Avicennia germinans, is a salt-tolerant woody species found along coasts and shorelines in the tropics and subtropical zones around the world (Andreu et al. 2022). Florida is home to three native mangrove species: black mangroves (Avicennia germinans), white mangroves (Laguncularia racemosa) (Medina Irizarry and Andreu 2023), and red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) (Medina Irizarry and Andreu 2023). Black and red mangroves have expanded their range along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts in Florida as winter temperatures have increased and sea levels have risen (Kennedy et al. 2020), increasing their abundance and even converting saltmarshes into mangrove forests. There are several factors that dictate mangrove range expansion on Florida’s coastlines. This publication is intended to educate the general public and land managers about the factors driving mangrove range expansion. Though all the mangrove species listed above have been expanding their northern range limit, for the purposes of this publication, we will focus on black mangroves, which are more prevalent than other mangrove species.

Credit: Paul Duff, UF/IFAS

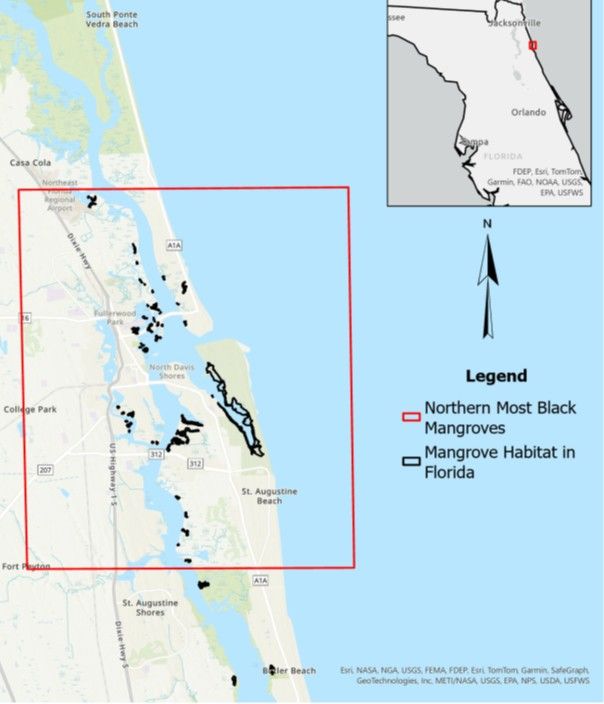

Current Range of Mangroves

Stands of black mangroves in Florida can be found as far north as the St. Augustine inlet on the East Coast of Florida (Figure 1) (Cavanaugh et al. 2014; Rodriguez et al. 2016) and the Big Bend on the Florida Gulf Coast (Giri and Long 2016; Rodriguez et al. 2016). Black mangroves have increased their range on both coastlines since the 1950s, growing into stands, or dense groups of trees and shrubs, even in north Florida, where previously they were sparsely distributed or not present at all. On the northern end of their range, mangroves take root within and grow in salt marsh habitats, sometimes fully converting these ecosystems to mangrove forests (Figure 2). Because mangroves often become established in existing habitats, their expansion is also referred to as “encroachment.” Although it is relatively simple to study mangrove stands, tracking and documenting the growth of individual mangrove trees is challenging. For example, some individual mangroves have been found north of the occurrences shown in Figure 1, including in Nassau County, Florida, and south Georgia (Vervaeke et al. 2024).

To forecast possible locations where mangrove expansion may occur, we review multiple relevant environmental factors, including temperature, land use, elevation, storm events, and salinity.

Environmental Factors of Range Expansion

Factors associated with expansion and contraction of mangrove ranges generally fall into two categories. The first set of factors, temperature, land use, and elevation, determine whether mangroves are able to root and survive. The second category of factors, storms and salinity, determine whether mangroves will be able to reproduce.

Credit: Britney Hay, University of Florida Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure and Environment

Temperature

Black mangroves are restricted to tropical and subtropical regions because they largely do not tolerate frosts and freezes (Cavanaugh et al. 2014; Osland et al. 2020). However, it is important to note that freeze tolerance depends on factors like the duration and frequency of freezes. For example, recent research indicates that black mangroves were able to recover from exposure to temperatures as low as −7℃ (approximately 19°F) (Osland et al. 2020) at a short duration. Freezes can cause both partial and total death of the plant. When water in plant tissues freezes, it breaks cell walls, killing tissue and preventing growth. The extent of damage determines if the entire plant will die or if re-growth is possible. Because short, infrequent freezes may not cause total mortality, there is some resilience to occasional cold temperatures.

This trend of tropical species expanding into higher latitudes is apparent not only in Florida, but worldwide (Saintilan et al. 2013) due to the reduced frequency and severity of freezes. In some cases, temperature barriers preventing northward movement no longer exist. For example, mean annual temperatures between Matanzas Inlet and Amelia Island to the north are no longer meaningfully different; the frequency and duration of freezes likely do not differ between these two latitudinal locations. This lack of difference provides the potential for mangrove expansion to continue northward.

Credit: Paul Duff, UF/IFAS

Land Use

Humans use land for a variety of purposes, including for industry, for residential development, and for recreation. Land is sometimes deliberately conserved in its natural state. Different land use types may encourage or inhibit mangroves from establishing at a given location. Mangroves may more easily expand into conservation areas composed of vegetated salt marsh than they do into industrial sites, which are usually protected by bulkheads or other non-vegetated shoreline stabilization structures. Understanding the current use of the property can help us forecast where mangroves are more likely to grow, providing valuable information about changes in mangrove ranges overall.

Elevation

Like land use, elevation can be used to predict potential locations for future mangroves. Each mangrove species grows best at a specific height above sea level, depending on its tolerance of being flooded by ocean tides. Trees that exist at lower elevations spend more time underwater, while those growing at higher elevations spend relatively more time exposed to air. In fact, most black mangroves are positioned to be out of the water during low tides (Figure 3). Black mangroves need to be positioned higher in the landscape and exposed at low tide (Alleman and Hester 2011; Rabinowitz 1978) so that their above-ground root systems (pneumatophores) can absorb oxygen (Numbere and Camilo 2022). These exposure requirements determine the ideal elevation within a tidal range where mangroves can establish. By understanding the elevations at which mangroves tend to establish and survive, researchers can identify potential areas to which mangroves may recruit in the future.

Storm Events

Mangrove reproduction is unique in that mangroves exhibit viviparity, or the bearing of live young (Alleman and Hester 2011). These viviparous seeds are called propagules, and are essentially small, living plants ready to grow in the sediment. The mangrove propagule can float within the water and be moved by wind and currents for a few weeks to a few months before settling on land (Alleman and Hester 2011). Dispersal or movement of mangrove propagules by storms is a key factor in northern range expansion. Tropical storms relocate mangrove propagules by wind and wave action, with increasing storm frequency potentially enhancing propagule dispersal. Without tropical storms, propagules do not disperse as far from the parent tree (Alleman and Hester 2011). Mangrove propagules have been found to travel farther in storm years than in non-storm years, facilitating mangrove expansion (Kennedy et al. 2020; Peterson and Bell 2012; Rodriguez et al. 2016).

Salinity

Propagule transport and survival depends on water salinity (Odum 1982). High-salinity water allows propagules to stay buoyant, or float in the water column, for a longer period of time compared to fresher water (Alleman and Hester 2011). Increased time spent buoyant improves the propagule’s chance of traveling longer distances and, therefore, of landing in an optimal habitat. In waterways that receive high freshwater inputs, like the Intercoastal Waterway, propagules may sink before establishing on shore. High salinity has also been found to prevent fungal growth (Alleman and Hester 2011; Rabinowitz 1978), which reduces propagule mortality. Therefore, waters with higher salinities may facilitate increased travel of mangrove propagules and decrease the rate of propagule mortality.

Discussion

Potential for Northern Range Expansion

Each factor discussed in this publication plays an important role in the future of Florida’s mangrove populations. Mangrove range expansion results in the establishment and spread of mangroves along shorelines where they were previously not able to survive. Mangrove expansion and encroachment into salt marshes will likely continue if not prevented by climatic barriers such as freezes. Research into water column salinity, coastal land use, and coastal elevation profiles will help predict how far propagules can travel from the parent colony.

Range Expansion Effects on the Public

Mangrove encroachment may directly affect members of the public who own waterfront property. Mangrove expansion can be a slow process, meaning waterfront property owners may struggle to see changes in their shoreline day-to-day. However, mangroves grow to be much bigger than salt marsh plants, meaning they can ultimately change the appearance of estuarine shorelines and, subsequently, the scenic views to which coastal residents are traditionally accustomed. Like salt marsh habitats, mangroves provide benefits such as shoreline protection and species habitat. In areas where noticeable mangrove encroachment is occurring, homeowners will need to learn about the regulations related to mangrove trimming and removal and the penalties for violating these rules.

The Florida legislature passed the Mangrove Trimming and Preservation Act (MTPA) in 1996 (Mangrove Trimming and Preservation Act 1996) to protect and conserve the state’s vital mangrove habitats. The Act acknowledged that mangroves perform many important functions that benefit people, animals, and the overall coastal environment. Among other roles, mangroves store carbon, protect homes and infrastructure from storms, and provide habitat for birds and fish. Because mangroves grow along intertidal shorelines, the MTPA also recognizes that, due to their height, mangroves can obstruct the views of coastal residents. To balance conservation and the aesthetic desires of coastal residents, the MTPA restricts and regulates mangrove trimming and removal. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) is responsible for developing and administering restrictions on mangrove destruction, including the requirements to obtain permits before trimming (Lee et al. in prep). It is therefore important for waterfront property owners to consider whether mangroves may expand onto their property, and how they may wish to balance the resulting ecological benefits with their needs as residents (e.g., shoreline access, ocean view).

Property Owner Responsibilities

Most alterations of mangroves, including trimming, require a permit through the FDEP. Some permits require a professional mangrove trimmer while other situations may be exempt from needing a permit. It is important that property owners contact their local FDEP office for official guidance. The FDEP website, floridadep.gov, includes a list of their offices. Any violation of rules and regulations related to mangroves can be costly to the property owner. Repercussions can include fines, penalties, and, in most cases, paying to reverse the alteration and re-establish the view-blocking stand of mangroves. Mangroves may be new to an area, but they are still protected under state law once they root in the sediment.

References

Alleman, L. K., and M. W. Hester. 2011. "Refinement of the Fundamental Niche of Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans) Seedlings in Louisiana: Applications for Restoration." Wetlands Ecology and Management 19 (1): 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-010-9199-6

Andreu, M. G., M. H. Friedman, M. M. Hudson, and H. V. Quintana. 2022. “Avicennia Germinans, Black Mangrove: FOR 259 FR321, 4 2013.” EDIS 2013 (4). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fr321-2013.

Cavanaugh, K. C., J. R. Kellner, A. J. Forde, et al. 2014. "Poleward Expansion of Mangroves Is a Threshold Response to Decreased Frequency of Extreme Cold Events." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (2): 723–727. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1315800111

Giri, C., and J. Long. 2016. "Is the Geographic Range of Mangrove Forests in the Conterminous United States Really Expanding?" Sensors 16 (12): 2010. https://doi.org/10.3390/s16122010

Kennedy, J. P., E. M. Dangremond, M. A. Hayes, R. F. Preziosi, J. K. Rowntree, and I. C. Feller. 2020. "Hurricanes overcome migration lag and shape intraspecific genetic variation beyond a poleward mangrove range limit." Molecular Ecology 29 (14): 2583–2597. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15513

Mangrove Trimming and Preservation Act, 403.9321-403.9333 F.S. (1996). https://www.flsenate.gov/Laws/Statutes/2018/403.9321

Medina Irizarry, N., and M. Andreu. 2023. "Rhizophora mangle, Red Mangrove: FR460/FOR389, 2/2023." EDIS, 2023 (1). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fr460-2023

Numbere, A., and G. Camilo. 2022. "Growth, Abundance, and Diversity of Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans) Pneumatophores in Deforested and Sand-Filled Mangrove Forest at Eagle Island, Niger Delta Nigeria."22 August 2022, PREPRINT (Version 2) available at Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1810526/v2

Odum, W. E., C. C. McIvor, and T. J. Smith III. 1982. The Ecology of the Mangroves of South Florida: A Community Profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Biological Services, Washington, D.C. FWS/OBS-81/24. 144 pp. Reprinted September 1985. https://sarasota.wateratlas.usf.edu/upload/documents/EcologyOfMangroves1982.pdf

Osland, M. J., R. H. Day, C. T. Hall, et al. 2020. "Temperature Thresholds for Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans) Freeze Damage, Mortality and Recovery in North America: Refining Tipping Points for Range Expansion in a Warming Climate." Journal of Ecology 108 (2): 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13285

Peterson, J. M., and S. S. Bell. 2012. "Tidal events and salt-marsh structure influence black mangrove ( Avicennia germinans ) recruitment across an ecotone." Ecology 93 (7): 1648–1658. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-1430.1

Rabinowitz, D. 1978. "Dispersal Properties of Mangrove Propagules." Biotropica 10 (1): 47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388105

Rodriguez, W., I. C. Feller, and K. C. Cavanaugh. 2016. "Spatio-Temporal Changes of a Mangrove–Saltmarsh Ecotone in the Northeastern Coast of Florida, USA." Global Ecology and Conservation 7:245–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.07.005

Saintilan, N., N. C. Wilson, K. Rogers, and A. Rajkaran. 2013. "Mangrove expansion and salt marsh decline at mangrove poleward limits." Global Change Biology 20 (1): 147–157 https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12341

Vervaeke, W., I. Feller, and S. Jones. 2024. "Ongoing Range Shift of Mangrove Foundation Species: Avicennia germinans and Rhizophora mangle in Georgia, United States." Estuaries and Coasts 48 (78): 9 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-025-01501-8