This EDIS publication provides insights for oyster consumers and the restaurants that serve them, offering recommendations on techniques to maximize the safety of oysters through proper cooking.

Introduction

Oysters are bivalve mollusks mostly found in brackish coastal waters (Martin et al. 2000). They are a low-calorie, low-fat food source, rich in vitamin B12, choline, selenium, iron, and zinc, as well as heart-healthy omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Oysters are an ideal food choice for those seeking a nutritious, balanced diet with a favorable ratio of unsaturated fats (Wright et al. 2018). Beyond their nutritional value, oysters offer unique odors and tastes.

Oysters harvested from approved waters are generally safe for raw consumption. However, oysters growing in contaminated waters may take up harmful microbes from the surrounding water through their natural filter-feeding activities (Wittman and Flick 1995). Consequently, consuming raw or undercooked contaminated oysters can pose risks for susceptible individuals, including toddlers, those with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, and the elderly. While having a lower risk of illness than raw oysters, eating undercooked oysters can still be hazardous (CDC 2025). It is important to note that the presence of harmful microbes may not alter the appearance, smell, or taste of oysters. Therefore, following best handling and cooking practices can help reduce the chance of foodborne illnesses. This EDIS publication aims to offer recommended practices on handling, preparing, and cooking oysters.

Essential Purchasing and Handling Practices Before Cooking

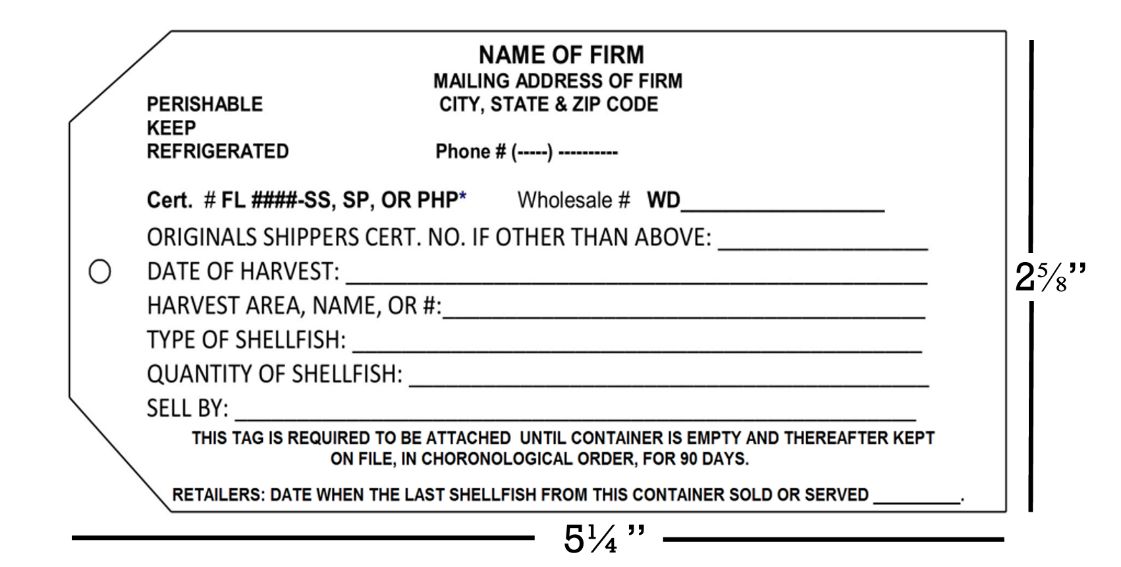

Purchasing oysters from reliable sources is the first step to ensure their wholesomeness. If oysters come from clean and safe waters (known as "approved" areas), the risk of contamination is significantly reduced. The seafood industry in the United States is subject to strict regulations to ensure food safety and protect public health. Oysters sold in grocery stores are harvested exclusively from approved waters that meet stringent quality and safety standards. In addition to these regulations, each batch of oysters is required to carry a "shellfish processor tag." According to the U.S. FDA, it is essential to check for tags on sacks or containers of live oysters (in the shell) and labels on containers or packages of shucked oysters. These tags and labels provide important information, including the processor's certification number, indicating that the oysters were harvested and processed according to national shellfish safety regulations (Figure 1).

Credit: Source: FDACS (2023)

If an oyster's shell is open and does not close when touched, it is likely dead and should not be used for consumption (FDA 2024). Fresh oysters should have tightly closed shells and a briny, sea-like aroma. Avoid consuming oysters with a fishy smell or any off odors, as this can indicate spoilage. For proper handling, store oysters in a cool and clean container to prevent contact with dirt or other germs. It is essential to place oysters on ice or in the refrigerator immediately after purchasing. If you plan to use the oysters within two days, store them in a clean refrigerator set to a temperature of 4°C (40°F) or below (FDA 2024). It is also advisable to scrub the oyster shells under running water before opening them to reduce the risk of transferring bacteria or other contaminants to the oyster meat.

Oyster Cooking Methods

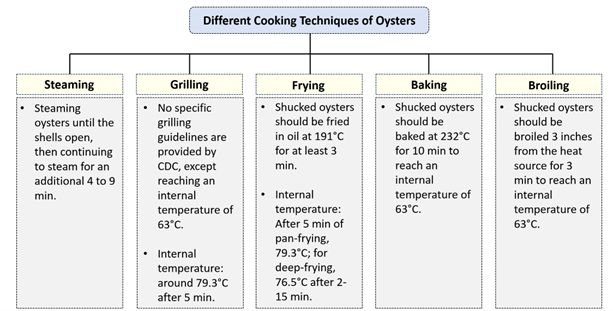

The European Union (EU) mandates that bivalve mollusks must be cooked to an internal temperature of 90°C (194°F) for 90 seconds (EFSA Panel 2015). In contrast, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends cooking oysters until they reach an internal temperature of 63°C (145°F) (CDC 2024). For optimal quality, cook oysters within a temperature range of 63°C to 78°C (145°F to 172°F), as temperatures above 78°C (172°F) would negatively impact their quality (Felice 2011). Table 1 shows information about common cooking practices of oysters.

Table 1. Definitions of common cooking practices of oysters.

Figure 2 summarizes the CDC's cooking method recommendations and internal temperatures of oysters after specific cooking durations (EFSA Panel 2015; Felice 2011). However, heat treatment can vary significantly, as oysters of different sizes and structures experience different heat transfer rates (Hu and Mallikarjunan 2005). Cooking adjustments, such as time, temperature, or cookware type, are often necessary to achieve the desired internal temperature (Leung et al. 2018). Extended heat exposure can affect the palatability of oysters, although it might be necessary to ensure food safety. To be thorough, verify cooking practices by using a food thermometer.

Credit: Sources: CDC (2024) and Leung et al. (2018)

Use of Thermometers to Ensure Safe Cooking

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) recommends that all consumers cook their food to a temperature that is at least equal to or greater than that stated on the safe minimum internal temperature chart (USDA-FSIS 2025b). Unfortunately, providing a specific time for safely cooking oysters is not possible, as their sizes vary widely by species, region, and harvest date. Therefore, using a food thermometer is the only way that individuals can ensure their food product reaches the appropriate internal temperature of 63°C (145°F) to kill harmful microbes (EFSA Panel 2015; Hu and Mallikarjunan 2005).

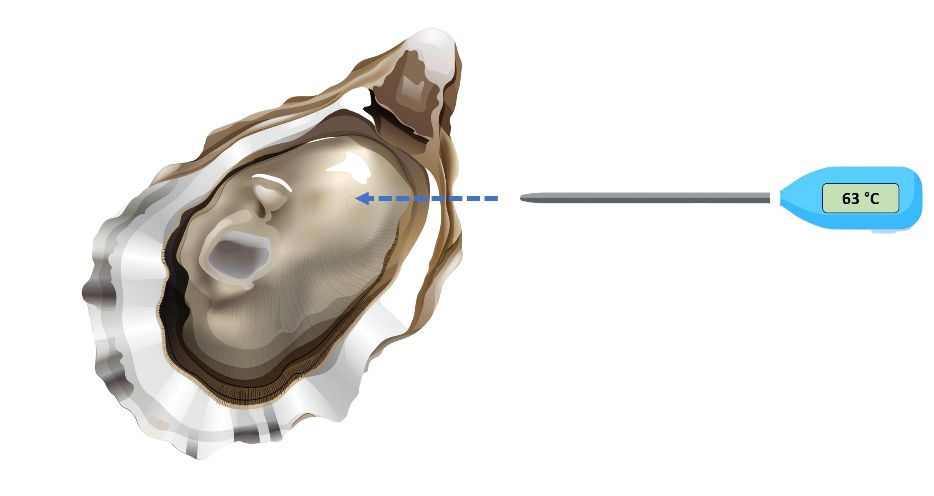

Proper thermometer use is essential for ensuring food safety and preserving desirable product characteristics. While many assume the color and firmness of a food indicate its internal temperature, this method is unreliable for confirming it has reached the minimum safe internal temperature (Feng and Bruhn 2019). A wide range of thermometer designs can account for differences in food products based on their composition and structure; the USDA outlines these on its website (USDA-FSIS 2025a). For a thin food product like an oyster, placing a thin thermometer with a small reading area in the thickest part of the oyster would be the most appropriate option (Figure 3) to ensure the most accurate measurement of the internal temperature (Mcleod 2009).

Credit: Designed by Freepik (www.freepik.com)

Conclusion

To ensure the safety of oysters, it is essential to purchase them from reliable sources, handle them properly, and cook them before consumption. The CDC recommends cooking oysters to an internal temperature of 63°C (145°F) to effectively minimize the risk of harmful microbes. Using a food thermometer is strongly advised to measure the internal temperature during cooking. This practice assures the oysters have reached the required temperature to make them safe to eat.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Foundational and Applied Science Program of Agriculture, grant no. 2023-67017-39184/project accession no. 1029851, and Research Capacity Fund (Hatch) programs, project numbers FLA-FOS-006540 (S1077) and FLA-FOS-006543 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

References

EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards. 2015. “Evaluation of Heat Treatments, Different from Those Currently Established in the EU Legislation, that Could Be Applied to Live Bivalve Molluscs from B and C Production Areas, that Have Not Been Submitted to Purification or Relaying, in Order to Eliminate Pathogenic Microorganisms.” EFSA Journal 13 (12): 4332. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4332

Felice, R. J. 2011. “Sensory and Physical Assessment of Microbiologically Safe Culinary Processes for Fish and Shellfish.” Master’s thesis, Virginia Tech. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/42494

Feng, Y., and C. M. Bruhn. 2019. “Motivators and Barriers to Cooking and Refrigerator Thermometer Use Among Consumers and Food Workers: A Review.” Journal of Food Protection 82 (1): 128–150. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-245

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS). 2023. “Shellfish Processing: Rules and Regulations.” FDACS-P-02067. Last revised May 2023. https://ccmedia.fdacs.gov/content/download/65886/file/shellfish-processing-rules-and-regulations.pdf

Hu, X., and P. Mallikarjunan. 2005. “Thermal and Dielectric Properties of Shucked Oysters.” LWT - Food Science and Technology 38 (5): 489–4946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2004.07.016

Leung, J., BCIT School of Health Sciences, Environmental Health, C. Andraza, L. McIntyre, and H. Heacock. 2018. “Evaluation of Internal Temperature of Oysters Following Standard Thermal Process Recipes.” BCIT Environmental Public Health Journal. https://doi.org/10.47339/ephj.2018.64

Martin, R. E., E. P. Carter, G. J. Flick, and L. M. Davis. 2000. Marine and Freshwater Products Handbook. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781482293975

Mcleod, C., B. Hay, C. Grant, G. Greening, and D. Day. 2009. “Localization of Norovirus and Poliovirus in Pacific Oysters.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 106 (4): 1220–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04091.x

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2024. “Preventing Vibrio Infection.” Last updated May 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/prevention/vibrio-and-oysters.html

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2025. BEAM (Bacteria, Enterics, Ameba, Mycotics) Dashboard. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed on May 6, 2025. www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dfwed/BEAM-dashboard.html.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS). 2025a. “Kitchen Thermometers.” Last updated March 21, 2025. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/kitchen-thermometers

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS). 2025b. “Safe Minimum Internal Temperature Chart.” Last updated April 14, 2025. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/safe-temperature-chart

U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2024. “Selecting and Serving Fresh and Frozen Seafood Safely.” Last updated March 5, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/selecting-and-serving-fresh-and-frozen-seafood-safely

Wittman, R. J., and G. J. Flick. 1995. “Microbial Contamination of Shellfish: Prevalence, Risk to Human Health, and Control Strategies.” Annual Review of Public Health 16 (1): 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pu.16.050195.001011

Wright, A. C., Y. Fan, and G. L. Baker. 2018. “Nutritional Value and Food Safety of Bivalve Molluscan Shellfish.” Journal of Shellfish Research 37 (4): 695–708. https://doi.org/10.2983/035.037.0403