Sweet corn is not just a side dish for summer barbecues. It is a delicious, crunchy vegetable that can be enjoyed throughout the year! Many love its natural sweetness, but sweet corn has a lot more to offer than great taste. So, why is sweet corn good for you? Which type of corn should you buy? Are you lacking ideas on how to cook it? This publication is for anyone interested in the potential health benefits of sweet corn and recipe ideas to incorporate more sweet corn into their dietary patterns.

Credit: Marisol Amador, UF/IFAS

Consumers agree that sweet corn is a budget-friendly food, whether fresh on the cob, frozen, or canned (Dahl and Moreno 2025). Fresh sweet corn on the cob is available from your local grocery store or farmers’ market whenever it is in season—usually late spring and summer. Cobs can be purchased with the husk intact or in plastic wrap with the husks removed. Corn cooks quickly, for 10 minutes or less, by boiling, steaming, or grilling to perfection. Frozen corn kernels and cobs, as well as cans of creamed or whole kernel corn, are available year-round. Flash freezing fresh corn preserves quality and nutrients. Canned sweet corn, being shelf-stable, is convenient for adding to lunches and dinners when in a rush.

How does sweet corn fit into dietary patterns?

From a global perspective, sweet corn is recognized as a key component of a healthy diet. The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems describes a healthy diet as “vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and unsaturated oils, includes a low to moderate amount of seafood and poultry, and includes no or a low quantity of red meat, processed meat, added sugar, refined grains, and starchy vegetables” (Willett et al. 2019). By their standard, sweet corn notably falls into the recommended “vegetables” category of a healthy diet, not with starchy vegetables such as cassava.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends dietary patterns that emphasize vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts to reduce the risk of chronic diseases (USDA and HHS 2020). The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) categorizes vegetables into five groups based on their relative nutrient contents: dark-green, beans and peas, starchy, red and orange, and other. Although botanically a grain, sweet corn is harvested before maturity at the “milk” stage and is considered by the USDA to be a starchy vegetable along with white potatoes, green peas, plantains, and cassava. It is recommended that adults consume about 5 cups of starchy vegetables such as sweet corn each week (USDA and HHS 2020).

According to the NOVA classification, which categorizes foods based on their level of processing (Monteiro et al. 2019), whole and separated corn are considered unprocessed foods, while canned corn is minimally processed. Consuming unprocessed and minimally processed vegetables such as sweet corn instead of ultra-processed foods promotes better diet quality and overall health.

What is the nutritional value of sweet corn?

A ½ cup serving of canned or frozen sweet corn provides about 55 calories, 12 grams of carbohydrates, and 2 grams of protein (USDA-ARS, n.d.). Sweet corn is also low in fat, with one medium cob providing 1 gram. Each medium cob of sweet corn provides about 2 grams of dietary fiber, which is necessary for supporting gut health and wellness (USDA-ARS, n.d.). Sweet corn also provides essential vitamins such as folate and minerals such as potassium, at 275 milligrams per medium cob (USDA-ARS, n.d.). Potassium content is particularly important as diets higher in potassium help prevent high blood pressure (Chia et al. 2025) and fatty liver disease (Chen et al. 2024). Consuming sweet corn may help meet the 2600 milligrams daily recommendation of potassium for adults to prevent deficiency and reduce the risk of chronic disease (NASEM 2019).

Credit: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS

What are some potential health benefits of sweet corn?

Eye Health

Carotenoids are plant pigments that function as antioxidants, which protect body cells and tissues from damage and reduce the risk of chronic disease. Yellow sweet corn contains high amounts of two unique carotenoids: lutein, named from the Latin word luteus, and zeaxanthin, from the Greek word xanthos, meaning yellow (Perry et al. 2009; Scott and Eldridge 2005). Lutein and zeaxanthin are the main pigments in the retina of the human eye. They protect the macula, which is the small, pigmented center of the eye’s retina, from damaging blue light and decrease the risk of vision loss in older populations (Abdel-Aal et al. 2013). Higher intakes of lutein and zeaxanthin increase macular pigment optical density (Wilson et al. 2021). They are also associated with a decreased risk of macular degeneration (Mrowicka et al. 2022), a leading cause of vision loss in older adults (Bugg et al. 2025). Additionally, consuming lutein-rich fruits or vegetables, including sweet corn, has been shown to increase blood carotenoid levels (Olmedilla-Alonso et al. 2021). There is some evidence to suggest that higher blood levels of lutein and zeaxanthin are associated with a decreased risk of cataract (Liu et al. 2014), which leads to cloudy vision.

Brain Health

Lutein and zeaxanthin accumulate in the brain (Widomska et al. 2016), where they are thought to have neuroprotective effects (Flieger et al. 2024). As antioxidants, they neutralize free radicals, unstable molecules that can cause damage to the brain through a process called oxidation. A higher intake of lutein and zeaxanthin is associated with better cognitive function among older adults (Devarshi et al. 2023). Dietary lutein may help prevent aspects of cognitive decline, specifically preserving executive function such as planning and reasoning (Li and Abdel-Aal 2021).

The MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) dietary pattern is associated with a lower risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. This dietary pattern is specifically designed for brain health, promoting vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and fish, while limiting foods such as red meat, butter, and fast food. The MIND diet is higher in lutein and zeaxanthin than other healthful dietary patterns (Holthaus et al. 2024). As corn and corn products are the main source of zeaxanthin in the US diet (Perry et al. 2009), sweet corn may be a key but underappreciated component of a brain-protective diet.

Cardiometabolic Health

Dietary lutein intake is associated with better cardiometabolic health. Higher intakes are associated with lower heart disease, stroke, and metabolic syndrome—a condition of multiple risk factors that increases the risk for heart disease (Leermakers et al. 2016). Lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation have improved HDL-C, “good” blood cholesterol, in elderly adults (Ghasemi et al. 2023).

High blood pressure, one component of metabolic syndrome, is aggravated by high dietary sodium. Daily sodium intake should stay below 2,300 milligrams according to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which corresponds to about 1 teaspoon of table salt (USDA and HHS 2020). Many brands of canned corn contain added salt. However, canned kernel corn is also available as “Low Sodium” and “No Salt Added,” ideal for those who want to avoid consuming too much sodium. Draining and rinsing the corn with water can help reduce the sodium content of canned corn kernels that have added salt.

High blood glucose (sugar) is another component of metabolic syndrome and may progress to type 2 diabetes. Glycemic index is a ranking of foods containing carbohydrates; foods with a high glycemic index cause higher spikes in blood glucose than those with a lower glycemic index. Box 1 describes how the glycemic index of corn is determined.

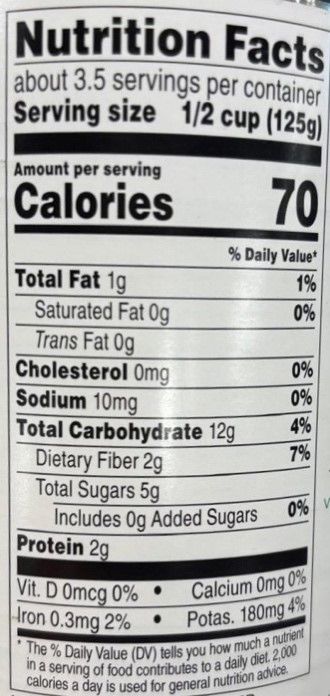

High glycemic index diets are associated with an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, diabetes-related cancer, and all-cause mortality (Jenkins et al. 2024). Additionally, a dietary pattern high in glycemic load is associated with increased levels of amyloid, an indicator of Alzheimer’s disease risk (Taylor et al. 2017). Fortunately, fresh sweet corn has a medium glycemic index, lower than many commonly consumed high-glycemic breads and cereals. Note that some canned corn products contain added sugar, which may affect the glycemic index. Be sure to check the ingredients list. The nutrition facts label will also show the amount of added sugar (Figure 3).

Glycemic index (GI) measures the area under the curve of the serum glucose concentration over the first 2 hours after consuming a carbohydrate-containing food and dividing this by the serum glucose response after consumption of an equal amount of glucose (50 grams). It is expressed from 0 to 100. Glycemic Load (GL) represents the grams of available carbohydrate multiplied by GI and divided by 100. Available carbohydrate is the total carbohydrate minus the fiber.

For example, a cob of sweet corn could have a glycemic index of 62 (glucose is 100), 27 grams of total carbohydrate, and 3 grams of fiber. Tocalculate the glycemic load:

27 grams of carbohydrate − 3 grams of fiber = 24 grams of available carbohydrate × 62/100 = 15 grams

Only 15 grams of the total 27 grams of carbohydrate will contribute to blood glucose within 2 hours after eating.

Credit: Audrey Mailly, formerly UF/IFAS

Gut Health

A large cob of sweet corn is a good source of dietary fiber. It is generally accepted that we should aim for at least 25 grams of dietary fiber per day (Clemens et al. 2012), and higher intakes are associated with a lower risk of chronic disease (Dahl and Stewart 2015). Only about 5% of the US population consumes the recommended dietary fiber (USDA and HHS 2020). Consuming more vegetables, such as sweet corn, will help increase dietary intake. Sweet corn contains primarily insoluble fibers, which may help prevent constipation. Freezing and canning sweet corn increases the insoluble fiber content (Whent et al. 2023). Cooked and cooled sweet corn contains resistant starch, as does raw sweet corn (Moongngarm 2013). Resistant starch is not digested by human enzymes and functions like dietary fiber. Resistant starch may be fermented by gut bacteria and support the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria in the gut (Dobranowski and Stintzi 2021). Additionally, sweet corn naturally contains no gluten, making it a suitable food for those affected by celiac disease or gluten intolerance.

Summary

Consuming sweet corn may contribute positively to overall health. Most importantly, sweet corn contains antioxidants and fiber, which may help reduce the risk of chronic disease. Sweet corn adds color to your plate, while providing lutein and zeaxanthin for eye and brain health. Increasing your dietary fiber by choosing to eat more vegetables, such as sweet corn, will benefit your overall health and reduce the risk of cardiometabolic disease. To ensure the optimal health benefits of sweet corn, choose fresh, frozen, or canned corn labeled with “low” or “no added” sodium. Below are some sweet corn recipe ideas.

Recipes

Sweet Corn and Pasta Salad

- 4 cups cooked corkscrew pasta, drained and cooled

- 1 can sweet kernel corn with no salt added or 2 cups frozen sweet corn kernels, thawed

- 1½ cups celery, chopped

- 1½ cups carrots, coarsely shredded

- 1½ cups sweet red, yellow, or orange sweet pepper, chopped

- 4 green onions, finely chopped

- ¼ cup feta cheese, crumbled

- ⅓ cup Greek salad dressing

Combine pasta, corn, celery, carrot, red pepper, onion, and feta in a large bowl. Add dressing to pasta mixture and toss to coat well. Refrigerate until serving. Makes 10 servings.

Corn and Black Bean Salad

- 1 can black beans, rinsed and drained

- 2 cups sweet kernel corn (freshly boiled and cut off the cob, canned with no salt added, or frozen and thawed)

- ¼ cup fresh cilantro

- ¼ cup lime juice

- 2 medium tomatoes (e.g., cherry), chopped or halved

- 1 teaspoon cumin

- Salt and pepper to taste

Combine all ingredients in a large bowl. Refrigerate and serve. Makes 10 servings.

Sweet Corn Dip

- 3 cups sweet kernel corn (freshly boiled and cut off the cob, canned with no salt added, or frozen and thawed)

- 2 tablespoons red onion

- ½ cup Greek yogurt

- 2 tablespoons lime juice or the juice of one lime

- 2 cloves of garlic or ¼ teaspoon powdered garlic

- ½ cup cilantro, chopped

Finely dice the onion and the garlic. Mix all the ingredients together and sprinkle the dip with cilantro. You can get creative with this recipe by adding bell peppers, cucumbers, avocado, or some tuna. To spice things up, you can add jalapeño or hot sauce. Finally, serve it with whole-wheat crackers for extra fiber. Makes 4 servings.

Santa Fe Chicken

- 1 can reduced-sodium black beans, drained

- 1 can sweet kernel corn with no salt added or 2 cups frozen kernels, thawed

- 1 cup salsa

- 4 skinless, boneless chicken breast halves

- 8 oz light cream cheese, cut into cubes

- 8 tortillas

Combine the black beans, corn, and ½ cup of salsa in a slow cooker. Lay the chicken breasts atop the black bean mixture; top with the remaining ½ cup of salsa. Cover and cook on High for 3 hours. Add cream cheese; cover and cook for another 30 minutes. Shred the chicken with two forks. Spoon the chicken mixture into the middle of each tortilla; roll the tortillas around the filling and serve. Makes 8 servings.

Masala Corn

- 3 cups sweet corn kernels (freshly boiled and cut off the cob, canned with no salt added, or frozen and thawed)

- 1 tablespoon butter, vegan butter/spread, or olive oil

- 1 tablespoon cilantro or fresh coriander, finely chopped

- 1 teaspoon chaat masala

- 1 pinch ground cayenne

- ⅛ teaspoon black pepper

- ⅛ teaspoon salt

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

Add the sweet corn to a microwave-safe bowl and top with butter or an alternative fat. Microwave for 1 to 2 minutes, stirring every 30 seconds until the butter has melted and the sweet corn is hot. Mix well. Chop the cilantro/coriander and add it to the bowl along with all the other ingredients. Mix well, taste, and adjust seasoning to personal taste as needed. Makes 4 servings.

Green Onion Corn Salad

- 3 cups sweet corn kernels

- 4 green onions

- 1 lime worth of zest and juice

- 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

- Salt* and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Place the sweet corn kernels in a bowl and add the green onions, lime zest and juice, and olive oil. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Toss gently to combine. Makes 4 servings.

*Adding salt will increase the sodium content of this recipe.

Cream of Corn Soup

- 2 cups thin white sauce (See Box 2)

- 1 (15-ounce) can of creamed corn

- ¼ cup of finely chopped onions

- 2 teaspoons olive oil

Sauté onions in olive oil. Combine white sauce, creamed corn, and onions. Heat and serve. Take care not to bring it to a boil. Makes 4 servings.

In a glass bowl, blend 2 tablespoons of vegetable oil (or melted fat) with 2 tablespoons of flour, ¼ teaspoon of salt, and a dash of pepper. Add 2 cups of milk a little at a time while stirring. Microwave until smooth and thickened, stopping to stir every 30 seconds. Makes 2 cups of sauce.

Easy Shepherd’s Pie

- 1 pound ground beef*

- ½ cup chopped onions

- 1 can creamed corn

- 1 package low-sodium instant mashed potatoes (prepare by following the instructions on the box)

- Salt and pepper to taste, or seasoning of your choice

- Grated cheese (optional)

Combine ground beef and chopped onions. Pan-fry until the ground beef is cooked and the onions are clear. Add salt and pepper to taste or experiment with seasonings of your choice. Pour the beef mixture into a casserole dish. Pour creamed corn on top of the beef mixture as the second layer (do not mix). Spoon instant mashed potatoes as the third layer and top with grated cheese. Bake until heated through to 165°F.

*Note: Plant-based ground beef alternatives (crumbles) can be substituted for ground beef. If precooked, skip the pan-fry step, simply sauté the onions until translucent, and combine with the ground beef substitute. Makes 4 servings.

References

Abdel-Aal, E.-S. M., H. Akhtar, K. Zaheer, and R. Ali. 2013. “Dietary Sources of Lutein and Zeaxanthin Carotenoids and Ttheir Role in Eye Health.” Nutrients 5 (4): 1169–1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041169

Bugg, V. A., K. Eppich, M. S. Blakley, F. Lum, T. Greene, and M. E. Hartnett. 2025. “Vision Loss and Blindness in the United States: An Age-Adjusted Comparison by Sex and Associated Disease Category.” Ophthalmology Science 5 (4): 100735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xops.2025.100735

Chen, H.-K., Q.-W. Lan, Y.-J. Li, Q. Xin, R.-Q. Luo, and J.-J. Wang. 2024. “Association Between Dietary Potassium Intake and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis in U.S. Adults.” International Journal of Endocrinology: 5588104. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5588104

Chia, Y.-C., F. J. He, M.-H. Cheng, et al. 2025. “Role of Dietary Potassium and Salt Substitution in the Prevention and Management of Hypertension.” Hypertension Research 48 (1): 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01862-w

Clemens, R., S. Kranz, A. R. Mobley, T. A. Nicklas, et al. 2012. “Filling America's Fiber Intake Gap: Summary of a Roundtable to Probe Realistic Solutions with a Focus on Grain-Based Foods.” The Journal of Nutrition 142 (7): 1390S—1401S. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.160176

Dahl, W. J., and M. L. Moreno. 2025. “Consumer Perceptions of the Health Benefits of Sweet Corn.” Journal of the National Extension Association of Family and Consumer Sciences 20: 25–37. https://www.neafcs.org/2025-journal-articles

Dahl, W. J., and M. L. Stewart. 2015. “Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Health Implications of Dietary Fiber.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 115 (11): 1861–1870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.09.003

Devarshi, P. P., K. Gustafson, R. W. Grant, and S. H. Mitmesser. 2023. “Higher intake of certain nutrients among older adults is associated with better cognitive function: An analysis of NHANES 2011–2014.” BMC Nutrition 9 (1): 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-023-00802-0

Dobranowski, P. A., and A. Stintzi. 2021. “Resistant Starch, Microbiome, and Precision Modulation.” Gut Microbes 13 (1): 1926842. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2021.1926842

Flieger, J., A. Forma, W. Flieger, et al. 2024. “Carotenoid Supplementation for Alleviating the Symptoms of Alzheimer's Disease.” International Journal Molecular Science 25 (16): 8982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25168982

Ghasemi, F., F. Navab, M. H. Rouhani, P. Amini, and N. Shokri-Mashhadi. 2023. “The Effect of Lutein and Zeaxanthine on Dyslipidemia: A Meta-Analysis Study.” Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators 164: 106691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2022.106691

Holthaus, T. A., S. A. Keye, S. Verma, et al. 2024. “Dietary Patterns and Carotenoid Intake: Comparisons of MIND, Mediterranean, DASH, and Healthy Eating Index.” Nutrition Research 126: 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2024.03.008

Jenkins, D. J. A., W. C. Willett, S. Yusuf, et al. 2024. “Association of Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load with Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and All-Cause Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Mega Cohorts of More than 100,000 Participants.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 12 (2): 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(23)00344-3

Leermakers, E. T., S. K. Darweesh, C. P. Baena, et al. 2016. “The Effects of Lutein on Cardiometabolic Health Across the Life Course: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 103 (2): 481–494. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.120931

Li, J., and E.-S. M. Abdel-Aal. 2021. “Dietary Lutein and Cognitive Function in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Molecules 26 (19): 5794. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26195794

Liu, X.-H., R.-B. Yu, R. Liu, et al. 2014. “Association Between Lutein and Zeaxanthin Status and the Risk of Cataract: A Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients 6 (1): 452–465. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6010452

Monteiro, C. A., G. Cannon, M. Lawrence, M. L. da Costa Louzada, and P. Pereira Machado. 2019. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System. FAO. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ca5644en

Moongngarm, A. 2013. “Chemical Compositions and Resistant Starch Content in Starchy Foods.” American Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science 8 (2): 107–113. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajabssp.2013.107.113

Mrowicka, M., J. Mrowicki, E. Kucharska, and I. Majsterek. 2022. “Lutein and Zeaxanthin and Their Roles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration-Neurodegenerative Disease.” Nutrients 14 (4): 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040827

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). 2019. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium, edited by M. Oria, M. Harrison, and V. A. Stallings. National Academies Press.

Olmedilla-Alonso, B., E. Rodríguez-Rodríguez, B. Beltrán-de-Miguel, M. Sánchez-Prieto, and R. Estévez-Santiago. 2021. “Changes in Lutein Status Markers (Serum and Faecal Concentrations, Macular Pigment) in Response to a Lutein-Rich Fruit or Vegetable (Three Pieces/Day) Dietary Intervention in Normolipemic Subjects.” Nutrients 13 (10): 3614. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103614

Perry, A., H. Rasmussen, and E. J. Johnson. 2009. “Xanthophyll (Lutein, Zeaxanthin) Content in Fruits, Vegetables and Corn and Egg Products.” Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 22 (1): 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2008.07.006

Scott, C. E., and A. L. Eldridge. 2005. “Comparison of Carotenoid Content in Fresh, Frozen and Canned Corn.” Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 18 (6): 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2004.04.001

Taylor, M. K., D. K. Sullivan, R. H. Swerdlow, et al. 2017. “A high-glycemic diet is associated with cerebral amyloid burden in cognitively normal older adults.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 106 (6): 1463–1470. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.162263

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS). n.d. FoodData Central. Accessed January 8, 2026. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2020. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025.

Whent, M. M., H. D. Childs, S. E. Cheang, et al. 2023. “Effects of Blanching, Freezing and Canning on the Carbohydrates in Sweet Corn.” Foods 12 (21): 3885. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213885

Widomska, J., M. Zareba, and W. K. Subczynski. 2016. “Can xanthophyll-membrane interactions explain their selective presence in the retina and brain?” Foods 5 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods5010007

Willett, W., J. Rockström, B. Loken, et al. 2019. “Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems.” Lancet 393 (10170): 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31788-4

Wilson, L. M., S. Tharmarajah, Y. Jia, R. D. Semba, D. A. Schaumberg, and K. A. Robinson. 2021. “The Effect of Lutein/Zeaxanthin Intake on Human Macular Pigment Optical Density: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Advances in Nutrition 12 (6): 2244–2254. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmab071