Terms to Help You Get Started

- Duct system. Collection of airways that distribute heated or cooled air to different rooms in a home

- HVAC. Heating. Ventilation, and Air Conditioning

- Conditioned air. Air that recycles through the HVAC system, returning the same volume of heated or cooled air back into the home

- Supply. Delivers conditioned air to a home through individual room registers (i.e., vents)

- Supply registers. Vent-like units in walls, floors, or ceilings where conditioned air blows

- Air handler. The indoor unit that moves the air through the heating/cooling system

- Return/return register or grille. Picks up inside air for reconditioning, drawing the air through a changeable filter to the air handler of the central system

- Cooling load. The amount of energy needed to maintain comfort levels in conditioned air

- Duct tape. Fabric based tape with a rubber adhesive used in many households for temporary fixes, but has been proven to become brittle and disintegrate over time

- Aluminum/foil tape. Specialty tape with an acrylic-based adhesive that performs consistently under extreme temperatures

- Mastic. A thick paste that provides a permanent seal at air-duct joints and connections; sometimes used in conjunction with a fiberglass mesh tape

Quick Facts

- Typical duct systems lose up to 40% of your heating or cooling energy.

- Leaky ducts make your HVAC work much harder—ducts leaking just 20% of the conditioned air passing through them cause your system to work 50% harder.

- Leaks in your duct system result in higher utility bills.

- Duct leakage can result in mold problems and potential health and safety issues.

- Sealing leaky ducts can save you hundreds of dollars annually.

So how does a duct system work, and why is it so important?

The duct, or air distribution, system used in cooling and heating your home is a collection of airways that distribute the heated or cooled air to the various rooms throughout the home. This branching network of round or rectangular airways—usually constructed of sheet metal, fiberglass board, or a flexible plastic-and-wire composite—is found within your home. The duct system is designed to supply rooms with air that is “conditioned”—that is, heated or cooled by the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) equipment—and to circulate or return the same volume of air back to the HVAC equipment.

Typical air-duct systems lose 25% to 40% of the heating or cooling energy put out by the cooling and heating system. Leaks, one way in which conditioned air is lost in the duct system, make the HVAC system work harder, thus increasing your utility bill. In addition, duct leakage can lessen comfort and endanger your health and safety.

Your duct system has two main air-transfer systems—supply and return. The supply side delivers the conditioned air to the home through individual room registers—what you feel blowing out of the registers. The return side withdraws inside air and delivers it to the air handler of your central system. All of the air drawn into the return duct(s) is conditioned and should be delivered back through the supply registers.

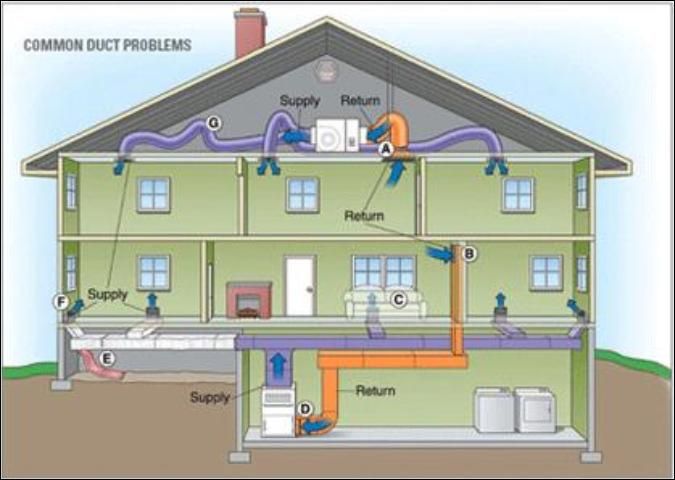

Figure 1 shows common areas where there are problems with the ducts and vents.

Credit: https://www.energystar.gov

What exactly happens if there is a leak in the duct system?

Because most ductwork is located in non-conditioned space such as attics, basements, garages, or crawl spaces, the HVAC system becomes an open system instead of a closed one. Leaking supply ducts can lose large amounts of cooled/heated air to these unconditioned areas. Leaking return ducts suck hot/cold unconditioned air into the conditioned space. Duct leakage significantly increases cooling and heating loads, sometimes beyond what the HVAC system can sustain.

The increased energy cost—because the HVAC system has to work harder—isn't the only effect of leaking ducts. Indoor humidity can increase when unconditioned air is introduced, leading to mold and mildew problems. If the air-handler unit is located in the garage and improperly sealed, return or supply leaks can introduce poor-quality outdoor air or hazardous vapors1 from the garage (from cleaning supplies, pesticides, gasoline, paints, car exhaust, etc.) into the home.

How do leaks occur?

Homes are not static systems, and conditions change as homes age. Tape adhesive dries out and caulking erodes. Many older systems that were installed before changes in residential building codes have supply registers in each room but only one centrally located return register for the whole home. When we close interior doors for privacy, air in that particular room can't flow out to a return register unless there is one located in that same room—but the supply register is still bringing in conditioned air. The delivered air has to go somewhere, so air gets forced out any space available. Meanwhile, enough air is not entering the return duct, so unconditioned air from the attic, basement, garage, or crawl space gets sucked in through leaking spots, cracks, or crevices. This situation can be avoided by having supply and return ducts in each room (as per current code changes), or by providing an air pathway between the room and the main body of the home. Such a pathway can be created by adding vents in doors or walls, or by installing a jumper duct or transfer vent that connects vents in the ceiling of each space. Also, keep furniture clear of air registers and return air vents. Anything that interferes with air circulation will make the system less efficient and potentially lead to problems.

Where do you look for leaks?

If there are areas of the home that seem colder or warmer than other areas, there could be an imbalanced distribution of air that needs to be adjusted (typically by a professional). Major leaks can be found around joints at ductwork connections, around the air handler unit, and near vents. Look for holes, tears, and loose joints. Every unsealed joint likely represents a small leak—even if a gap is not visible. Make sure registers and vents are firmly attached. If your home has an interior mechanical closet, it should also be properly sealed to prevent negative return-side air leakage. The return chamber should be kept free of debris.

How often should the duct system be checked for leaks?

Ductwork should be inspected once a year for leaks. Some utility companies and energy raters offer energy audits or diagnostic tools like blower-door, duct-blaster, and pressure-pan tests to detect leaks the homeowner cannot easily see. The relationship between supply and return ducts and air movement in the system is complex, and sometimes a homeowner, in fixing one problem, may inadvertently create another. Professionals can sometimes spot such potential problems before they happen.

What is the best way to seal the leaks?

It is best to have a licensed HVAC contractor repair your system's duct leaks. Return duct leaks are difficult to detect because the larger return ducts operate at a lower air pressure, and air is being drawn into the system. If you only repair the supply duct leaks, even more unconditioned air may be drawn into the system. Supply-duct leaks are more easily noticed because you can feel air blowing out from the connections or see nearby insulation moving.

Duct leaks can be sealed using mastic or acrylic-adhesive foil tape. Mastic adheres well to most surfaces and provides an effective long-term seal. Mastic alone may be used to seal cracks less than ¼" wide. Foil tape carries a 20-year guarantee if applied properly. The most effective method is to apply fiber-mesh tape first, and then seal it with mastic.

Any sealant should carry the Underwriters Laboratories rating (UL-181) specific for that particular type of duct. Most duct manufacturers now list the closure products that they allow to be used with their ducts.

If you see the contractor bringing in duct tape, make certain they do not intend to use it on ducts. If they do, then hire someone else. In the past, many systems were sealed with a gray rubber-adhesive, cloth duct tape. This tape will eventually disintegrate due to its short-lived rubber-based glue. If you see this kind of tape in an existing home, be sure to check all areas where it is attached to the ductwork. If your contractor insists on using duct tape on the ductwork, use a different contractor.

When building a new home, where should the ductwork be located?

In new residential construction, the best option is to locate the duct system within the conditioned space. Doing so can reduce your heating and cooling costs and improve your indoor air quality. When all the ducts are located within the building envelope,2 even if return leaks do occur, the air infiltrating the system is already conditioned. Supply leaks can still be a problem in that you won't get even distribution of conditioned air throughout the home. Therefore, proper sealing of ductwork is still very important—even when the duct system is located within the conditioned space. Note that the Florida Building Code, among other things, requires all duct distribution systems be sized and designed in accordance with recognized engineering standards such as ACCA Manual D or other standards. (ACCA stands for Air Conditioning Contractors of America, https://www.acca.org).

Why is the location of ductwork important?

Location is important because ducts placed in unconditioned attics, basements, garages, or crawl spaces waste energy if improperly insulated—another major cause of energy loss. Additionally, most homes have leaks in both the return and supply sides of the duct system. Locating ductwork in conditioned spaces decreases the temperature difference if leaks do occur.

Do you have any suggestions for the short-term?

Yes, there are some measures you can take now to get the most out of your duct system:

- Change/clean the filters on your return register regularly to optimize airflow.

- Adjust the positioning of your home furnishings so that none of the supply registers are blocked.

- Use weather stripping on the inside edge of your registers to prevent air leaks into wall crevices.

- Contact your local utility company for a home energy audit.

Summary

Evaluating the efficiency of your ductwork is just one way to save on energy costs. For more information about HVAC systems, other appliances, and additional resources for improving your home’s overall energy efficiency, refer to the Sustainable Living section of https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/.

1 VOCs: Volatile organic compounds

2 The enclosed, conditioned space within the home

References and Resources

Florida Building Code. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://floridabuilding.org

U.S. Department of Energy – Better Duct Systems for Home Heating and Cooling. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy05osti/30506.pdf

U.S. Department of Energy – Improving the Efficiency of Your Duct System. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/publications/pdfs/building_america/27630.pdf

U.S. Department of Energy – Minimizing Energy Losses in Ducts – Accessed February 18, 2025. https://energy.gov/energysaver/minimizing-energy-losses-ducts