"Everything would be fine if my partner would just change!" This is a common sentiment many of us have felt. However, this notion is just the opposite of how we should go about changing our relationships for good. Positive change is never easy.

Helpful Information

Change Yourself First

The principle of Change Yourself First is a healthy strategy for changing our relationships. This principle implies that we work on the things we can control (i.e., things we need to change about ourselves that can benefit our relationships) rather than focusing on the things we would like others to change (i.e., things over which we really have no control) (Figure 1).

Credit: Milt Putman, UF/IFAS

How Does Real and Lasting Change Occur?

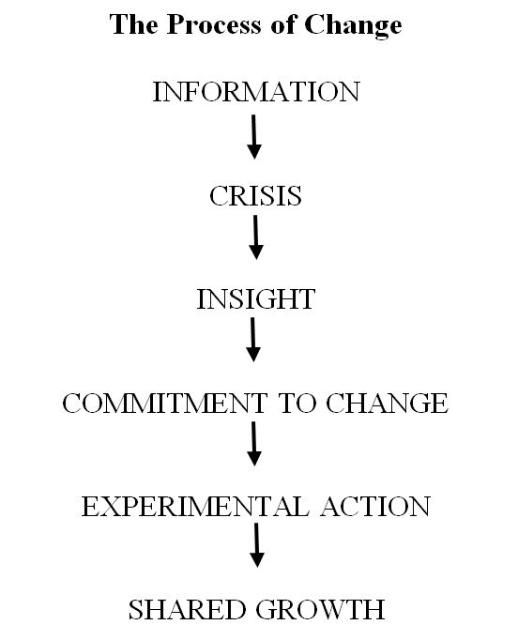

Real and lasting change is a unique process for every individual and each relationship (Mace, 1981). The process of change begins as we seek or are exposed to information we can apply to some aspect of our lives (Figure 2). This incoming information has the potential to really speak to our unmet needs and desires, such as feeling like we are worthwhile or longing to experience closer and more loving relationships. Often, this new information is recorded in our mind as a perceived crisis. A crisis occurs because we may realize, for example, that we are lacking the skills to show affection or to resolve conflict successfully. This process of realization is called insight.

As we become aware of our unmet needs and desires, the commitment to change unfolds. This commitment to change may then lead us to want to try some kind of experimental action to see if we can improve things. This might include an increased desire, for example, to read as much as possible about the addiction process, explore communication issues in a relationship, create a financial plan, learn how to parent a difficult child, or to seek a therapist when relationships become stagnant.

For example, one husband shared the following:

I remember a time as a student when, in an introductory marriage and family relations course, I learned about a list of rules for negotiating conflict successfully. As I read through the rules [information], I realized that I was breaking more than half of them in conversations with my wife [crisis]. This made me realize that I wanted to improve these skills [insight]. I copied the rules onto a piece of paper, which I carried with me for the next month [commitment to change]. I read through the rules almost every day, recalled past arguments, and explored potential ways I could change things in the future by using these rules successfully [experimental action]. Then, as conflicts arose, I was able to use these rules I had learned. My wife realized I had made some changes, and she began to learn the skills, as well [shared growth]. (Harris, Johnson, & Olsen, 2010, p. 14)

Change and Shared Growth

The results of change include enlightenment, fulfillment, satisfaction, increased confidence, greater life balance, and shared growth with others. Here's an example of how change and shared growth can occur:

I remember a time years ago when my fifteen-year-old daughter had climbed into the car and locked out her twelve-year-old brother. He asked her to unlock the door and let him in. She said, "Tell me I'm beautiful, and then I'll open the door." My son looked at her through the window and said, "That's just a power-and-control tactic. Now open the door!" When they realized I was watching, we all looked at each other and began to laugh. Because our children had witnessed me and my wife identify power-and-control tactics on many occasions, this awareness had become a part of them. Change had occurred among our children, and we didn't even realize it. (Harris, Johnson, & Olsen, 2010, p. 13)

When we change for the better, we change the dynamics of all of our surrounding close relationships for good. This includes being able to identify a power-and-control tactic used by an older sister. Indeed, change can become the spark that ignites new life into lifeless relationships. It can truly become the pot of gold (i.e., happy and satisfying relationships) not just at the end of the rainbow, but it can also grant us the reward of new relationship knowledge and skills all along our journey.

Things You Can Use

Take a minute to list the top three things you can do to change your relationships for the better (Table 1). Put this list somewhere where you will see it every day, such as next to the mirror or on the refrigerator, and then get moving toward your goal. Good Luck!

Helpful Websites

National Healthy Marriage Resource Center - http://www.healthymarriageinfo.org

Stronger Marriage - http://www.strongermarriage.org/

References

Harris, V. W., Johnson, A. C., & Olsen, K. M. (2010). Balancing work and family in the real world. Plymouth, MI: Hayden McNeil.

Mace, D. (1981). The long trail from information-giving to behavioral change. Family Relations, 30, 599–606.