"For all but our most recent history, dying was typically a brief process. Whether the cause was childhood infection, difficult childbirth, heart attack, or pneumonia, the interval between recognizing that you had a life-threatening ailment and death was often just a matter of days or weeks." —Atul Gawande in "Letting Go" (Gawande, 2010)

Introduction

Mortality has been a taboo subject for many years. It has even been said that the US has a "death-phobic" culture (Strainchamps, 2014). Recently, there have been signs of increased openness to talking about death as a natural part of life and the human condition (Strainchamps, 2014; Frangou, 2016; Gawande, 2015). Many cultural, demographic, educational, and policy changes have played a part in this shift.

Credit: UF/IFAS

-

Writers with terminal illnesses have bravely documented their end-of-life experiences, opening up the realities of dying in inspiring books (Frangou, 2016).

-

Advocates for thoughtful advance care planning that lays the groundwork for "a good death" have made their work accessible through major news outlets (Gawande, 2015).

-

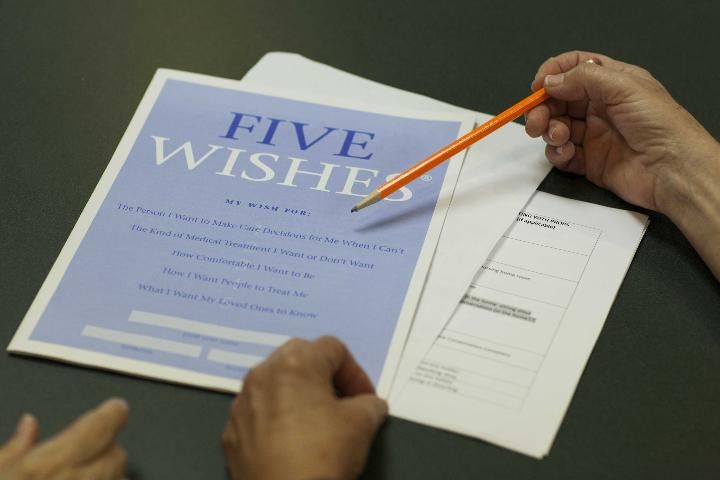

Educational programs such as National Healthcare Decisions Day and 5 Wishes® have brought attention to the value of advance health care planning (Berry, n.d.).

-

Policy changes have required health care institutions to provide information about advance directives (National Healthcare Decisions Day, n.d.).

-

Medicare now covers end-of-life conversations between a patient and a physician (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015).

-

The media are giving more coverage to dying and death by airing programs such as PBS's Frontline special, Facing Death (Frontline, 2010).

Nevertheless, it is not always easy to talk about death. Many of us shy away from this topic. Around one-fourth of adults living in the US have not considered the type of medical care they want as well as other end-of-life decisions. Although two-thirds have talked with someone about their preferences, only one-third have written these down. It is difficult for others to know and follow their loved ones' wishes regarding end-of-life care without clear communication and outlined preferences (Pew Research Center, 2013).

This is the first publication in a series called The Art of Goodbye that is designed to help you think about what a peaceful death would look like for you and plan accordingly. The "end of life" is usually defined as the time period when health care providers think that an individual's death may occur within six months. In this time frame, the patient as well as the patient's family or friends will need to make choices about the use of life-prolonging technology, pain management, and even the preferred place of death. During this vulnerable time, compassionate care, respect for personal preferences, and good communication are paramount. People fear that their preferences will be ignored, or they will endure excessive pain and have to be supported by a machine for a lengthy period of time (APA, n.d.).

Most older adults want to discuss and influence decisions about their care (APA, n.d.). They may not know what their options are or have information in order to plan in advance. This series discusses the major topics you need to address, supplies information you need, and gives ideas to begin conversations with family and/or friends and health care providers in advance. With information about available options and communication with loved ones and health care providers, individuals can lay the groundwork for preferred methods of care when the time comes and rest assured that their preferences will be respected (APA, n.d.).

Credit: UF/IFAS

Because the end of life is a very personal matter, The Art of Goodbye does not prescribe one way to handle these decisions. Instead, the program offers information and experiences to help people feel comfortable, informed, and at peace with their decisions and better able to communicate with others. This series is for individuals who want to:

-

Reflect on personal preferences and decide which type of health care they want at the end of their life.

-

Develop awareness of the choices available to them.

-

Learn about options for health care, final arrangements, and finances.

-

Be able to use effective communication skills in discussions with family and/or friends about important end-of-life decisions.

-

Make the plans they want for the end of their life.

-

Feel confident and satisfied with the steps they are taking.

Other publications in this series provide practical information. In this document, we give some background on major social changes that have, in large part, made the end of life a topic of conversation today.

Changes in Living and Dying

Credit: UF/IFAS

The dramatic increase in life expectancy in the 20th century was the result of major improvements in human health (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2015). In the US, many more people are living into their eighties, nineties, and even hundreds (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2013). Older adults currently comprise almost 13% of the US population. By 2030, that number is projected to increase to 20%, or one-fifth of the population (72 million). The fastest growing segment of the aging population consists of those 85 years and older (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2013).

Adults in the US now live longer thanks to public health strategies and improvements in both medical care and personal lifestyle choices that have reduced or eliminated the threats of certain historically deadly diseases (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2013). Chronic diseases, particularly heart disease and cancer, are currently the leading cause of deaths among older adults. Dying used to be a quick process. In certain cases, life can now be prolonged through medical interventions, as shown in Table 1.

-

A hundred years ago, people were born and died in their own homes while loved ones cared for them, most often for days or a few weeks.

-

Today, people are most often born in a hospital and die in old age in an institutional setting, such as a hospital or skilled nursing facility.

Preferences for the End of Life

Credit: UF/IFAS

A startling fact is that while most people say they would prefer to die at home without extreme care measures, most patients die in hospitals with more aggressive care than they wanted. Unfortunately, dying alone is a possibility in an institutional setting if visiting hours have ended and family and friends have gone home, or if loved ones cannot or simply do not visit. Many people fear they have been abandoned and may suffer physical and emotional distress at the end (APA, n.d.; US Department of Health & Human Services, 2010).

The Importance of a Substitute Decision Maker in Health Care

When someone is unable to make decisions themselves (e.g., they have dementia or have suffered a stroke), family members are often left to make decisions, especially about health care, without direct input from the individual. This is more likely among the elderly and critically ill. For instance, a large national study of adults 60 years and older who had died between 2000 and 2006 found that 40% needed decisions made regarding medical treatment. Of this group, 70% were not able to make decisions themselves (Bravo et al., 2012; Wendler & Rid, 2011).

Leaving the responsibility of making life-and-death decisions to someone else can be very stressful. In the national study mentioned above, approximately one-third of decision-making surrogates had emotionally or psychologically stressful, painful, traumatic, and long-lasting experiences. They frequently had doubts whether they had made the right decision (Wendler & Rid, 2011). Advance planning for care is one way someone can clarify and communicate their preferences for future care to substitute caregivers and health care providers in the event that the individual becomes unable to speak for themselves at a later date (Bravo et al., 2012). Written advance directives (ADs, including the Living Will portion) and conversations with family members and health professionals have many benefits, including:

-

Self-determination in making decisions

-

Better end-of-life medical care

-

Decreased burden related to substitute decision-making for loved ones

-

Reduced stress, anxiety, and depression in surviving relatives

-

Reduced usage of unwanted forms of life support (Bravo et al., 2012; Silveira, Kim, & Langa, 2010)

The Importance of Communication

Most older adults have completed advance directives for medical care. That rate has increased in the past few decades. Nevertheless, only one-third of all US adults have written down their preferences, which is about the same as a decade ago. On the other hand, six in ten US adults have talked with someone about their choices (Pew Research Center, 2013). The best combination is committing your preferences to paper on documents designed for these purposes and talking with your substitute decision maker(s).

Completing a living will or similar document does not guarantee that your preferences will be observed. However, your surrogate will be better able to decide and advocate for you if you have discussed what you want (Silveira, Kim, & Langa, 2010). For more information about making health care decisions, communicating with loved ones, and completing advance directives and important legal documents, see the other publications in this series. Another useful publication is The Conversation Project's Starter Kit that helps people write and talk about their preferences for their end-of-life care (theconversationproject.org/starter-kit/intro).

In a survey, 80% of people say if they became seriously ill they would want to talk about end-of-life care with their physician, but only 7% actually report having had an end-of-life conversation with their doctor (California Health Care Foundation, 2012). This is a gap that can be bridged by the patient and the physician. Health care providers sometimes lack the confidence to discuss end-of-life issues due to inadequate training or lack of experience in this area. For more information about communicating with health care providers, see the related publication in this series.

Summary

Today, there are more options for end-of-life medical care than there were in the past. This also means that people are faced with questions such as:

-

What kind of care do you want?

-

Whom do you want to make decisions for you, should you become unable to speak for yourself?

Communicating your preferences in writing and in discussions with your family and health care provider increases the chances that things will go as you want at the end of life. Through communication and proper preparation, individuals can positively affect their end-of-life experience.

To that end, information is key. The publications in this series are intended to encourage individuals to positively affect their own futures through self-reflection, exploration, communication, and discovery.

Credit: UF/IFAS

This series goes along with an educational program by the same name. To learn more about The Art of Goodbye: End of Life Education and find out how you can attend, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

References

APA. (n.d.). End-of-life care fact sheet. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.apa.org/pi/aging/programs/eol/end-of-life-factsheet.aspx

Berry, R. (2011). The origins of National Health Care decisions—The short version. Accessed on October 3, 2016. http://www.nhdd.org/blog/2011/3/4/the-origins-of-national-healthcare-decisions-the-short-versi.html

Bravo, G., Arcand, M., Blanchette, D., Boire-Lavigne, A. M., Dubois, M. F., Guay, M....Bellemare, S. (2012). Promoting advance planning for health care and research among older adults: A randomized controlled trial. BioMed Central, 13(1). DOI: 10.1186/1472-6939-13-1

California Health Care Foundation. (2012). Final chapter: Californians' attitudes and experiences with death and dying. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2012/02/final-chapter-death-dying

Frangou, C. (2016). How to talk about death and dying. Avenue. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.avenuecalgary.com/City-Life/Long-Reads/How-to-Talk-About-Death-and-Dying/

Frontline. (2010). Facing Death. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/facing-death/

Gawande, A. (2010). Letting go. The New Yorker, August 2. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/08/02/letting-go-2

Gawande, A. (2015). Oliver Sacks. The New Yorker. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/09/14/oliver-sacks

Institute of Medicine. (1997). Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press. DOI: 10.17226/5801.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2015). 10 FAQs: Medicare's role in end-of-life care. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/10-faqs-medicares-role-in-end-of-life-care/

National Healthcare Decisions Day. (n.d.). Federal Patient Self-Determination Act. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.nhdd.org/facts

Pew Research Center. (2009). End-of-life decisions: How Americans cope. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2009/08/20/end-of-life-decisions-how-americans-cope/

Pew Research Center. (2013). Views on end-of-life medical treatments. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/11/21/views-on-end-of-life-medical-treatments/

Silveira, M. J., Kim, S. Y. H., & Langa, K. M. (2010). Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. New England Journal of Medicine, 362, 1211–1218. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901.

Strainchamps, A. (2014). Americans don't talk much about death, but that may be changing. To the Best of Our Knowledge (PRI), November 16, 2014. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.pri.org/stories/2014-11-16/americans-dont-talk-much-about-death-may-be-changing

The Conversation Project. (2016). The Conversation Project. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://theconversationproject.org/

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2010). End-of-life. National Institutes of Health. Accessed on September 30, 2016. https://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/Pdfs/EndOfLife(NINR).pdf

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2013). The state of aging and health in America. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed on September 30, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/features/agingandhealth/state_of_aging_and_health_in_america_2013.pdf

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). Living longer. National Institutes of Health. Accessed on September 30, 2016. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global-health-and-aging/living-longer

Wendler, D., & Rid, A. (2011). Systematic review: The effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Annals of Internal Medicine, 154(5), 336–346. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008