Citrus can be grown under protective screen structures for fresh-fruit production to exclude the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP, Diaphorina citri)—which is the vector of the causal pathogen of huanglongbing (HLB), or citrus greening disease—and thereby produce disease-free healthy fruit. The benefits of eliminating HLB are immediate and include rapid, normal tree growth, higher yields of premium-quality fruit, negligible fruit drop, and uncomplicated fertilizer and irrigation requirements. Because CUPS is a relatively new citrus production system with new challenges, current guidelines are undergoing constant refinement by adoption of new research findings.

The CUPS significantly increases the cost of establishing a citrus grove due to the high cost of screen-house construction (on average $1 per square foot). We evaluated the potential of six high-density polyethylene (HDPE) screens, ranging in mesh size from 17 to 50, to exclude ACP from citrus grown in CUPS production systems. We concluded that screens with rectangular openings need to limit the short side of the openings to no more than 384.3 µm with an SD of 36.9 µm (= no less than 40 mesh) to prevent psyllid from passing through the screen. The long side of the openings can be at least 833 µm, but the efficacy of screens exceeding this value should be tested before using.

The recommended 40- to 50-mesh screen may need replacement every 7 to 10 years, depending on exposure to tropical storm winds; replacements come at a lower cost than the entire structure. High-quality construction, including setting support poles in concrete, can help minimize potential wind-related damage in the future. Pests, such as mites, thrips, citrus leafminer (CLM), scales, and mealybugs may selectively enter through the permeable screen, while some of the larger pest predators are excluded. Most of these pests are significantly reduced compared to their populations outside, such as with CLM; and their infestations may be localized and easy to manage when detected early. However, the environment in the CUPS may better suit some pests, such as the citrus rust mite and the citrus red mite, to develop high populations. Although parasitoids of several pests—including scales, mealybugs, and CLM—and small predators such as predatory mites were regularly detected in the CUPS, they were not detected enough to provide full control of target pests. Greasy spot and other fungal diseases may also thrive in the more humid conditions of the screen-house environment. These nonlethal but economically important pests and diseases must be adequately controlled with integrated pest management approaches customized for CUPS to avoid loss of fruit quality and yield.

It is important to monitor CUPS on a regular basis for pests and diseases to implement control either by manually removing infested foliage or spray treatments at an early stage of pest incursion to avoid dealing with high populations and spread. Yellow sticky traps for ACP and pheromone traps for male CLM are effective in detecting adults of these pests. However, visual examination of shoots is also required to check for larval infestations of CLM, thrips, scales, and mealybugs in the tree canopies. A magnifying lens is important in the detection of pest mites, thrips, and small predators such as predatory mites. The tap sampling method conducted in the tree canopies is useful in dislodging pests such as ACP, thrips, citrus red mites, and predatory mites onto a laminated sampling sheet where they are counted.

The ACP was successfully excluded long-term by the UF/IFAS screen-house structures for as long as there was no damage to the screen. Only one adult psyllid was found on a yellow sticky trap in the UF/IFAS Citrus Research and Education Center (CREC) CUPS during nearly six years of weekly scouting and monitoring, and only one tree tested positive for HLB out of about 1,000 trees at that time. During the summer of 2020, a localized ACP outbreak occurred in the CREC CUPS, following the period in March 2020 when the screen was completely replaced. The psyllids were controlled with comprehensive repeated insecticide sprays, and to date (9 years), HLB incidence is about 0.5%. The ACP was also detected at very low levels in the CUPS located at the UF/IFAS Indian River Research and Education Center (IRREC)—mainly adults in the yellow sticky traps and some shoot infestation with immatures. Most of those infestations resulted from the damage to CUPS caused by Hurricane Irma and were cleared immediately through manual removal of infested shoots followed by maintenance sprays of insecticides, which also helped lower the populations of other pests detected in the CUPS. No HLB incidence has been confirmed in the four CUPS structures at IRREC. Several species of predatory mites and parasitoids as well as their potential prey, such as mites, CLM, scales, and mealybugs, were observed in the CUPS. For ACP and other pests, the most vulnerable entry point of a screen house is through the doors from the movement of personnel and equipment, so standard decontamination procedures should be followed. In particular, citrus leaves and other grove debris that adhere to personnel or equipment should be carefully removed before personnel enter a CUPS facility, because grove debris could carry live ACP eggs, nymphs, or adults that can be dropped in the screen house and cause an infestation. Double-door or foyer entrances (Figure 1) are the minimum requirement for preventing ACP entry into CUPS, and the trees should be regularly inspected for ACP and signs of their feeding damage on leaves.

Credit: Arnold W. Schumann, UF/IFAS

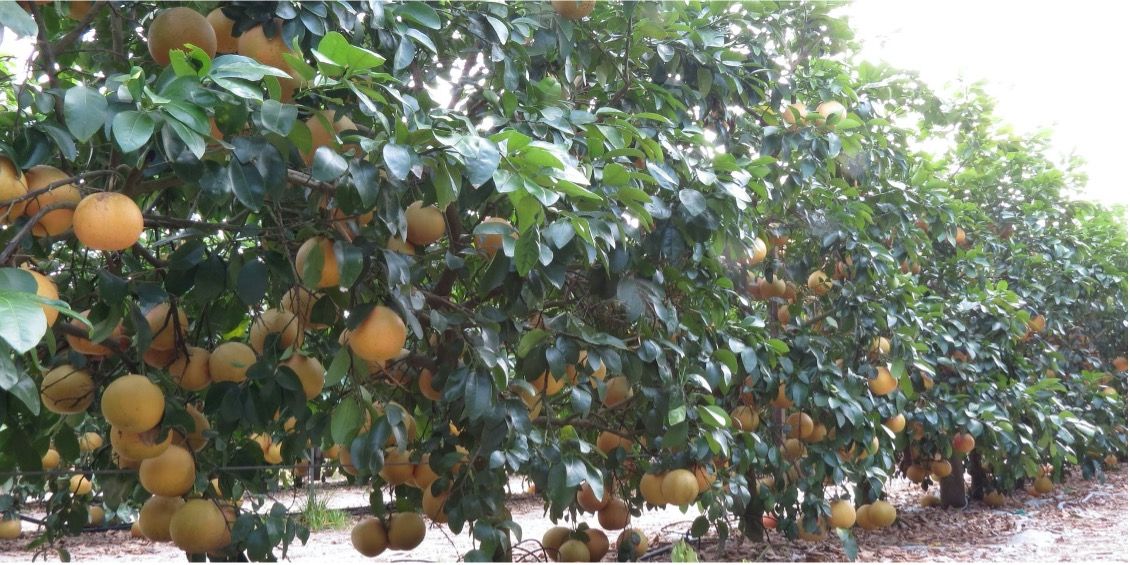

The expected economic benefit from adopting CUPS and excluding the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) to prevent HLB infection is increased yield and quality of fruit, which in turn, are expected to contribute to increased sustainability and profitability of citrus production. We evaluated the profitability of CUPS assuming the investment is for Fresh Ray Ruby grapefruit. The main source of data is the experimental CUPS at the CREC in Lake Alfred, Florida, for which production and input data is available for years 1 through 7 out of a 10-year horizon. For the years for which data was not yet available, the annual cash flows were estimated using sensible yield, packout rates, and prices assumptions and projections. We found that, when the grower insures the CUPS structure against hurricanes at a cost of $2,200 per acre, the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) ranges from 9.21% to 13.10% as the cost of the structure decreases from $1.03 per sq. ft. to $0.69 per sq. ft.; this implies that the investment in CUPS is profitable when the cost of capital is less than the obtained IRR. The profitability of the investment in CUPS is driven not only by the increased yield per acre and high packout rates resulting from ACP exclusion but also by the significant increase in the prices of fresh fruit in the last few seasons. From 2016/17 to 2020/21, grapefruit production in Florida decreased from 7.8 to 4.1 million boxes, which represents a 53% decline. From years 3 to 7 of the CUPS investment, the price per box of a size 32 fresh grapefruit increased from $36.74 to $52, which represents a 42% increase.

Early-maturing fresh-fruit varieties have additional advantages over late-maturing varieties because their fruits have to be protected from pests and diseases for less time. Thus, the risk of freeze damage to fruit is reduced, and routine pruning operations, including mechanical hedging and topping, can be conveniently conducted in the time between the end of harvest and the following bloom.

Trees can be grown in the ground and also in pots inside the CUPS (Figure 2), although pots are not recommended. In-ground trees developed a fuller canopy more quickly than potted trees, although fruit yields were similar within the first three years. Juice quality, however, can be better (higher Brix and acidity) for potted than in-ground trees. Results after seven years of growing citrus trees in pots of various sizes and designs at the CREC CUPS showed that after about five years of high productivity, the trees became root-bound, causing lower vigor, diminished fruit size, and lower yields. Trees were successfully transplanted into the ground, where they recovered within one year and were producing 855 boxes/acre in year 7.5 (Figure 3). We currently recommend that citrus grown in CUPS should only be planted in the ground to ensure long-term sustainable production.

Credit: Arnold W. Schumann, UF/IFAS

Credit: Arnold W. Schumann, UF/IFAS

The fruit yields in CUPS should also be produced as early as possible to achieve the desired early return on investment. Several different cultural methods for accelerating growth and optimizing early yields are being studied in the UF/IFAS CUPS facilities at the CREC, IRREC, and SWFREC. These include intensive hydroponics with daily or hourly delivery of all essential nutrients by drip fertigation to the trees; higher planting densities (871 and 1,361 trees per acre); selecting heat-tolerant, self-pollinating, seedless, precocious varieties without strong alternate-bearing habits; dwarfing rootstocks for limiting tree size when trees are grown in the ground; growing trees in containers to limit tree sizes with any rootstock; and canopy, irrigation, and fertilization management.

The CUPS is increasingly being adopted by growers in Florida, with over 1,500 planted acres in 2025. As most CUPS growers are now entering their first producing years, with others reaching that stage in the next couple of years, they are encountering challenges regarding fruit quality and yield. Among these challenges are, depending on the variety selected, variable yield over the years and lack of adequate peel color. These are not uncommon problems in the varieties grown under CUPS, but as a new system with unique conditions, it requires new approaches to solve them in the new environment. One main advantage of CUPS is that trees are HLB-free and the level of stress can be controlled. For this reason, classical techniques of grove management may be adopted. Ways to improve cultural management procedures include deficit irrigation, manual pruning, and gibberellic acid treatments, as well as photoselective screens, reduced late-season nitrogen fertilization, and brassinosteroid treatments to achieve better fruit color. For both Sugar Belle and Tango mandarins, deficit irrigation (watering both trees in the ground and in pots once every 15 days to field capacity for 2 months, December and January) can be adopted to increase yield. Our data shows a 30% fruit yield increase for both varieties, whereas gibberellic acid treatment (10 ppm spray) at petal fall of Sugar Belle grown in the absence of cross-pollination increased fruit set by 2.5 fold. Similarly, deficit irrigation and brassinosteroid treatments at the beginning of peel color change can be implemented to promote both internal and external fruit maturation: our data show higher Brix after deficit irrigation and both higher Brix and significant advance in peel coloration after brassinosteroid treatments in Tango mandarins. In an experiment with Honey Murcott where preharvest fruit peel color during December was correlated with leaf tissue N, the leaf N concentrations in the optimum range (2.5% to 2.7%) were associated with greener peel colors, while leaf N concentrations in the lower ranges (2.2% to 2.4%) were associated with redder peel colors. Corresponding fruit Brix measurements followed a similar trend whereby lower leaf tissue N during the fruit maturation stage favored higher Brix. These treatments to improve fruit quality still need to be refined to find the most favorable window of treatment efficacy. More information about fertilizer splitting and timing to improve yields and fruit quality is available in chapter 15, "Nutrition Management for Citrus Trees."

In conclusion, CUPS is a relatively new citrus production system for growing HLB-free fresh fruit. It works by near-total exclusion of the ACP vector. This solution to HLB may seem simple but in reality is more complex, relying on novel integrated approaches for optimizing all management practices, including pest and disease management, planting densities, variety and rootstock selection, irrigation and fertilization, hedging and topping, harvesting, and marketing. Noteworthy additional advantages of CUPS are that trees remain free of citrus canker, citrus leaf miner is easier to control, and trees and fruit are protected during hurricanes.

Credit: Arnold W. Schumann, UF/IFAS

Credit: Arnold W. Schumann, UF/IFAS