Introduction

Plant breeders and researchers have sought to improve crops since the dawn of agriculture. For hundreds of years, conventional breeding has had a tremendous impact on agricultural productivity. Over the last few decades, researchers have begun to transfer DNA between species in what is known as genetic engineering (transgenic technology). Recently, crop breeding programs started turning to CRISPR gene editing as a means to support commodity development. Considerable efforts have been devoted to applying this gene editing technology in modern agriculture to increase crop yields and improve the quality of food ingredients, especially by many of the major agronomic seed-producing companies. In this article, we outline the recent research updates and regulations on gene editing in crop improvement. The target audience for this report is the general public, including both scientists and nonscientists.

What is CRISPR and how does it work?

CRISPR, or clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, is a gene editing technology derived from a bacterial defense mechanism. This defense mechanism works in three phases. Phase 1, or Adaptation, occurs when a bacteriophage (or other type of invader) infects bacteria by injecting a small amount of DNA into the cell (Vigouroux & Bikard, 2020). During Adaptation, short fragments of the injected DNA are "saved" by the bacteria within a repetitive region of the genome, referred to as a CRISPR array (Vigouroux & Bikard, 2020). Each array consists of a unique spacer derived from these short fragments, which is interspaced between repeats. During Phase 2, the CRISPR locus is then transcribed and processed, resulting in short RNA sequences, which correspond to the sequences of the invading DNA fragments (Vigouroux & Bikard, 2020). Phase 3, Interference, uses the RNAs processed during Phase 2 as guides for Cas nucleases to create double stranded breaks (DSBs) in the invading DNA, effectively cutting it to pieces (Vigouroux & Bikard, 2020). The native bacterial DNA is protected from DNA damage because the Cas nucleases require a proto-spacer adjacent motif (PAM) site immediately adjacent to the recognized sequence (Doudna & Charpentier, 2014), which is not present in the bacterial DNA.

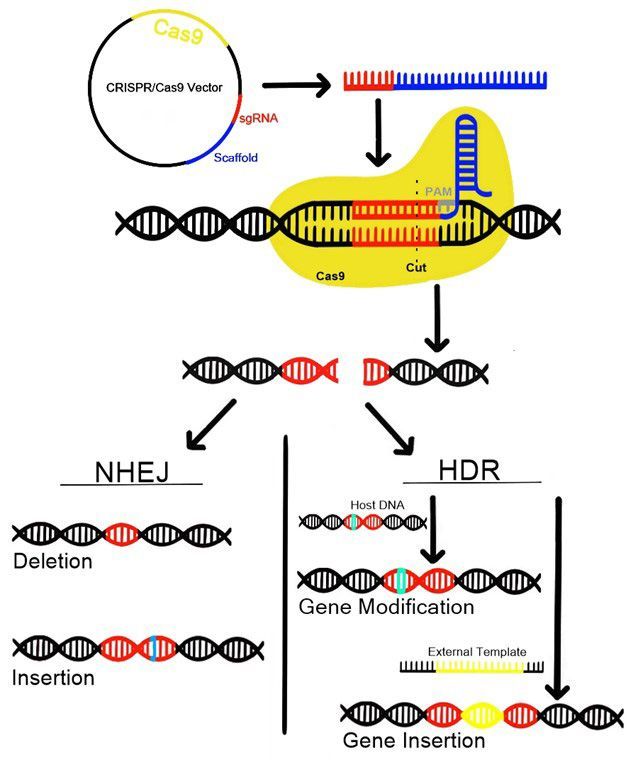

CRISPR/Cas-mediated gene editing technology takes advantage of this naturally occurring defense mechanism by synthetically adding guide sequences, referred to as guide RNAs (gRNAs), into a CRISPR locus (Figure 1). The lengths of these gRNA sequences vary depending on the Cas nuclease being used and can be designed using a wide range of available software. Cas9 is one of the most common Cas nucleases used in gene editing in plants. Cas9 recognizes a 3 nucleotide (nt) PAM sequence, 5’-NGG-3’, where N represents any nucleotide, and most often utilizes gRNA sequences which are 20nt in total length. Variations of Cas nucleases have been engineered to require different PAM sequences, allowing for greater flexibility in selecting targets for gene editing (Hillary and Ceasar, 2023).

Credit: Kaitlyn Vondracek

Once the guide sequences are cloned into a CRISPR vector, plant tissue is transformed using one of many methods. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and biolistic transformation via the use of a gene gun are two of the more common transformation methods used in plants, though new methods are continuously being developed for improved editing efficiency as well as for transgene-free applications. Once transformation is complete, the CRISPR/Cas system functions in a similar manner as it does in bacteria. The guide sequences which were cloned into the vector are transcribed and processed into gRNAs which match up to specific locations in the host genome. If the correct PAM site is present adjacent to the matching host sequences, the selected Cas nuclease will be recruited to generate a DSB at that position. If the correct PAM site is not present, the nuclease will not cut the DNA and will move to check the next site which matches the gRNA.

Mutations due to CRISPR gene editing are the product of the DNA repair mechanisms for DSBs. There are two main mechanisms for DSB repair in eukaryotes, non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) (Figure 1). HDR utilizes a template, either the sister chromatid of the target chromosome or a template which is externally supplied, to repair the break in the DNA. Using HDR, one can generate a precise insertion or other modification by including the desired sequence as the template. Conversely, NHEJ occurs in the absence of a template and instead relies on an error-prone repair mechanism, which often results in a random insertion or deletion at the position of the break. It is also possible that no error occurs during NHEJ, in which case the host DNA will be indistinguishable from before it was cut.

How does CRISPR gene editing technology improve crops and benefit the public?

Using the CRISPR gene editing technique, researchers can selectively “edit” plant genomes to obtain desired traits. Gene editing is often confused with other transgenic crop improvement approaches (the products of which are colloquially referred to as “genetically modified organisms (GMOs)”) and referred to as the same idea. Schneider et al. (2014) described clearly the differences between genetically modified (GM) foods and GMOs as well as other possible benefits of gene editing for crop improvement. In other EDIS articles (Lee et al. 2016, 2018), we have also described what gene editing techniques are, how they differ from transgenic approaches, and their potential applications for cultivated strawberries.

CRISPR gene editing technology has been applied to numerous crops to modify a wide range of traits (Table 1). For example, to increase yield in tomato, Lippman and colleagues at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory performed gene editing to develop plants with double the number of branches (Rodríguez-Leal et al. 2017; Rothan et al. 2019). Gene editing has also been applied in tomatoes to enhance nutritional quality and improve resistance to biotic and abiotic stress, traits which would otherwise take decades to improve through traditional breeding methods (Krishna et al. 2019). Gene editing can also help to address disease resistance. Huanglongbing (HLB), or citrus greening, is a devastating disease of citrus worldwide and has reduced Florida citrus production by more than 50% (Graham et al., 2020). There are currently few genetic resistance sources available for HLB-resistance breeding (Dodds et al., 2017; Khachatryan and Choi 2017; Palangasinghe et al., 2024), but Dr. Nian Wang’s group at UF/IFAS has begun working to generate HLB-resistant citrus lines using CRISPR-based gene editing, which could potentially save the Florida citrus industry. Important quality traits in various foods can also be improved using gene editing technology. For example, reduced-gluten wheat, non-browning mushrooms and apples, and soybeans with reduced unhealthy saturated fats can be obtained using CRISPR gene editing tools (Waltz, 2016; Jacobs et al., 2015; Sánchez-León, et al. 2017). Table 2 lists additional crop species in which gene editing has been applied, as well as the current status of the relevant research.

What CRISPR gene edited foods are available in grocery stores?

Gene edited soybean oil, cold-storable potatoes, high-fiber and gluten-reduced wheat, and lower-saturated-fat canola have been developed by Calyxt (formerly Cellectis Plant Sciences, Inc., now Cibus). Calyxt’s gene edited soybean oil was cleared by the USDA in 2018 and went on the US market in 2019. A further improved “next generation” was announced in May of 2021, but it’s unclear whether products containing the improved trait made it to market (“Calyxt Announces Next Generation Premium Soybean”, 2021). While Calyxt’s high-fiber wheat was cleared by the USDA in 2018, it has not commercialized to date. Starting in 2019, Cibus began cultivating gene edited herbicide resistant canola (SU Canola + Draft herbicide growing system) in North Dakota and Montana. USDA-APHIS cleared herbicide tolerant flax and rice from Cibus in 2020, and waxy corn from Corteva in 2021. Following a merger in 2023, Calyxt became part of Cibus, which now holds more than 1,000 issued and pending patents for gene editing in agriculture and have developed several traits which have been incorporated into several breeding germplasms (“Cibus Announces Closing of Merger”, 2023).

The EPA will not regulate edited camelina with increased oil content from Yield10 Bioscience, which is now in pre-commercial seed production (“Yield10 Bioscience Obtains Nonregulated Status”, 2018). Furthermore, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) additionally cleared new gene edited camelina lines from Yield10 Bioscience in 2024 (“USDA-APHIS Determines that Yield10 Bioscience’s”, 2024; “Yield10 Bioscience Announces”, 2024). Pairwise released gene edited high-nutrient romaine and low-pungency mustard greens for commercial sale in 2023 (Brown, 2023) and is additionally working on gene editing in strawberry, blackberry, and raspberry. In total, Pairwise holds 21 exemptions from regulation for genome edited crops, with research continuing in a range of crops (Barefoot, 2024).

Gene edited crops are also becoming more widely available in the global market. In 2020, Japan’s regulatory agencies approved gene edited tomatoes with increased γ-aminobutyric acid (also known as GABA) content, and Alora (formerly Agrisea), a United Kingdom-based company, secured permission for field trials of salt-tolerant gene edited rice which started in 2023 (Watson, 2023). In 2022, Argentina’s Biosafety Commision (Comisión Nacional de Biotecnología Agropecuaria or “CONABIA”) cleared Yield10 Bioscience’s gene edited camelina (“Yield10 Bioscience Receives Favorable Ruling”, 2022), and Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) and Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) cleared Corteva’s waxy gene edited corn in 2023 (United States Department of Agriculture, 2023). Biosafety authorities in Kenya are also preparing to release genetically modified corn, cassava, and potato from regulation in the near future, with an additional 42 GM crops in the release pipeline (Gitonga, 2024).

Current Regulations and Policies for CRISPR Gene Edited Crops

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy issued the Coordinated Framework for Regulation of Biotechnology with the advent of recombinant DNA in the 1980s. In the United States, three Federal agencies—the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—were charged with the implementation of laws regulating biotechnology products (Food and Drug Administration, 2023). The EPA mainly regulates bioengineered products intended for pesticidal purposes, biofertilizers, bioremediation, and the production of various industrial compounds, including biofuels. As such, the EPA will not regulate CRISPR-edited plants as long as the altered traits are not for synthesis of toxic chemicals such as pesticides or biofuels. Similarly, the FDA focuses on the safe regulation of genetically engineered foods that can be used for dietary supplements, cosmetics, drugs, and medical devices. The FDA ensures food products comply with legal requirements, regardless of their production methods (whether traditional or gene edited). The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) authorizes the importation, interstate movement, and environmental release of plants that may pose a plant pest risk. Regulation of genetically modified and gene edited crops by USDA-APHIS began in 1987 under the Coordinated Framework for Regulation of Biotechnology, 7 CFR part 340 (United States Department of Agriculture, 2022). Further revisions to APHIS’s regulatory policy were made in May of 2020 and included several changes to the existing system.

Research on the CRISPR-Cas9 system for gene editing and crop improvement is being performed worldwide, but there is still no internationally agreed-upon regulatory policy for gene edited products. In the United States, the FDA, EPA, and USDA-APHIS have taken different steps toward regulating agricultural products produced by new plant-breeding technologies, including CRISPR gene editing. The FDA has no additional requirement for the food safety assessment of gene edited crops. In 2024, guidelines for companies to voluntarily engage with the FDA prior to marketing gene edited foods were released. These voluntary guidelines will allow companies to outline food safety precautions taken and may help to ease transition of new gene edited plant products to the commercial market (Bickell, 2024). The FDA will continue to apply a risk-based approach to gene edited foods with a focus on the objective characteristics and intended use(s). However, the FDA will still regulate gene editing used in animals as “new animal drugs.”

On May 24, 2023, the EPA announced a final rule for an exemption proposed in October of 2020 regarding regulation of plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) (Environment Protection Agency, 2023; Mendelsohn et al, 2023; Stockstad, 2023). PIPs are pesticidal substances which are produced in and used in and used by plant as pesticide (Mendelsohn et al., 2023). The 2023 final rule reflects advancements made in biotechnology since 2001, when PIPs derived from conventional breeding were exempted from regulation while maintaining regulatory requirements for PIPs produced through biotechnology (Environmental Protection Agency, 2023). Under the final rule, gene edited plants will be exempt from the in-depth review process if the introduced trait already exists within the plant’s gene pool and if data is submitted indicating the gene edited plant won’t harm the plant’s ecosystem or cause harm to consumers (Stokstad, 2023). This regulatory change comes as a result of significant advancements in biotechnology which enable the creation of PIPs through gene editing and genetic engineering that are virtually indistinguishable from those produced using traditional breeding methods (Environmental Protection Agency, 2023). On March 28, 2018, USDA Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, issued a formal statement on innovative plant-breeding techniques (including CRISPR gene editing), explaining that the USDA does not have plans to evaluate gene edited plants for health and environmental safety if they could otherwise have been developed through traditional breeding, unless these gene edited plants are potential plant pests or developed using plant pests (United States Department of Agriculture, 2018). The 2020 revisions to 7 CFR 340 provide a more in-depth definition for plants eligible for non-regulated status (United States Department of Agriculture, 2020(b)). Under these updates, regulations do not apply to organisms which contain one of the following modifications: cellular repair of targeted double-stranded break in absence of externally provided template (7 CFR 340.1(b)(1)), targeted single base pair substitution (7 CFR 340.1(b)(2)), or introduction of a gene known to occur within the plant’s gene pool, change of target sequence to match a known allele within the plant’s gene pool, or targeted changes to correspond to a known structural variant in the plant’s gene pool (7 CFR 340.1(b)(3)). A plant can additionally be considered non-regulated following submission of exemption proposals by either USDA-APHIS or an external party if the resulting modification(s) could be achieved through conventional breeding (7 CFR 340.1(b)(4)(i) and 7 CFR 340.1 (b)(4)(ii)). On May 14, 2020, USDA Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, announced a press release revealing a final rule to update USDA regulations of biotechnology under the plant protection act (United States Department of Agriculture, 2020(a)). This final rule, titled the Sustainable, Ecological, Consistent, Uniform, Responsible, Efficient (SECURE) rule, will enable more efficient and effective regulatory oversight by focusing on risks posed by traits introduced during gene editing rather than whether the gene edited plant was developed using a plant pest (Hoffman, 2021; United States Department of Agriculture, 2020(a)). The SECURE rule additionally includes a mechanism for rapid initial review to identify and separate plants which do not plausibly increase plant pest risk from those that do (Hoffman, 2021). Plants which are identified to plausibly increase plant pest risk will be subject to further regulation.

In contrast to the United States, the European Court of Justice has ruled that gene editing techniques fall within the European Union’s 2001 GMO directive, meaning that gene- edited products should be treated like traditional transgenic products (Faure and Napier 2018) and be subjected to a mandatory risk assessment (Callaway 2018). According to Faure and Napier, CRISPR gene editing technology will not be profitable in the European Union and is unlikely to be implemented soon. However, loosened restrictions of gene edited plants have been considered recently, and the European Parliament voted to ease regulation of gene edited crops in early 2024 (Stokstad, 2023,2024; “EU rethinks genome editing”, 2023; Voigt, 2023).

Several scientists in Europe together with the European Commission’s top scientific advisory panel have sharply rebuked both the European Court decision on gene editing and Europe’s entire framework for regulating genetically modified organisms (Conrow, 2018; Pothering, 2019). Gene editing is also currently considered GM in New Zealand and controlled by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA). While gene edited crops are still heavily regulated globally, several countries have started loosening restrictions on edited crops, including India (Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology Department of Biotechnology, 2022), Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, Israel, Japan, and Australia (Menz et al., 2020). While the EU and New Zealand have yet to loosen restrictions for gene edited crops, there are calls for updates to the regulatory systems based on decades of regulatory experience and consumer studies (Dayé et al., 2023; Van Der Meer et al., 2023; Voigt, 2023).

Conclusion

CRISPR gene editing techniques are fundamental breakthroughs in plant genetic improvement that can adjust desired traits more quickly and precisely than traditional breeding. In recent years, gene editing has been applied in many crop systems to improve important agronomic traits such as yield, nutritional value, and disease resistance. However, there remains some public concern and regulatory uncertainty over food ingredients from gene edited crops. Nevertheless, such foods will soon be available on supermarket shelves, and therefore it is important that the development and regulatory status of gene edited foods is clarified and that consumers are adequately informed about new technologies.

References

Barefoot, H. (2024). Pairwise earns USDA exemption confirmations for genomic edits in berries. Pairwise. Available at https://www.pairwise.com/news/pairwise-earns-usda-exemption-confirmations-for-genomic-edits-in-berries

Bickell, E. G. (2024). Gene-Edited Plants: Regulation and Issues for Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov

Brown, B. (2023). Pairwise introduces Conscious™ greens into U.S. Restaurants. Pairwise. Available at https://www.pairwise.com/news/pairwise-introduces-conscious-greens-into-u.s.-restaurants

Callaway, E. (2018). CRISPR plants now subject to tough GM laws in European Union. Nature, 560. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05814-6

Calyxt Announces Next Generation Premium Soybean Product Line Performance Best-In-Class for High Oleic, Ultra-Low Linolenic Profile |Press Release (2021). Cibus, Inc. https://investor.cibus.com/news-releases/news-release-details/calyxt-announces-next-generation-premium-soybean-product-line

Cibus Announces Closing of Merger with Calyxt to Create Industry Leading Precision Gene Editing and Trait Development Company | Press Release. (2023). Cibus, Inc. https://investor.cibus.com/news-releases/news-release-details/cibus-announces-closing-merger-calyxt-create-industry-leading

Conrow, J. (2018). Top science panel criticizes EU’s GMO regulations. Alliance for Science. https://allianceforscience.org/blog/2018/11/%20top-science-panel-criticizes-eus-gmo-regulations/

Dayé, C., Spök A., Allan, A. C., Yamaguchi, T., & Spink, T. (2023). Social Acceptability of Cisgenic Plants: Public Perception, Consumer Preference, and Legal Regulations (pp. 43–75). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10721-4 3

Dodds, N. M. W., Gorham L. M., & Rumble J. N. (2017). Floridians’ Perceptions of GMOs: GMOs and Florida Citrus. AEC520. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/wc182

Doudna, J. A., & Charpentier, E. (2014). The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-cas9. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1258096

Environmental Protection Agency (2023). Pesticide; Exemptions of Certain Plant-Incorporated Protectants (PIPs) Derived from Newer Technologies. (FRL No. 7261-04-0CSPP). https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-05/PrePubCopy-FRL-7261-04-OCSPP-PIPs-Final-Rule_0.pdf

EU rethinks genome editing. (2023). Nature Plants, 9(8), 1169–1170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01505-x

Faure, J. D., & Napier, J. A. (2018). Europe's first and last field trial of gene-edited plants? eLife, 7, e42379. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.42379

Food and Drug Administration. (2023). New Plant Variety Regulatory Information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-new-plant-varieties/new-plant-variety-regulatory-information

Gitonga, A. (2024). National Biosafety Authority ready to release three GMO crops. The Standard; Standard Digital. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/counties/article/2001496148/national-biosafety-authority-ready-to-release-three-gmo-crops#google_vignette

Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology Department of Biotechnology. (2022). Standard Operating Procedures for Regulatory Review of Genome Edited Plant under SDN-1 and SDN-2 Categories. https://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/SOPs%20on%20Genome%20Edited%20Plants_0.pdf

Graham, J., Gottwald, T., & Setamou, M. (2020). Status of Huanglongbing (HLB) outbreaks in Florida, California and Texas. Tropical Plant Pathology, 45(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-020-00335-y

Hillary, V. E., & Ceasar, S. A. (2023). A Review on the Mechanism and Applications of CRISPR/Cas9/Cas12/Cas13/Cas14 Proteins Utilized for Genome Engineering. Molecular Biotechnology, 65(3), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-022-00567-0

Hoffman, N. E. (2021). Revisions to USDA biotechnology regulations: The SECURE rule. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(22). http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004841118

Jacobs, T. B., LaFayette, P. R., Schmitz, R. J., & Parrott, W. A. (2015). Targeted genome modifications in soybean with CRISPR/Cas9. BMC Biotechnology, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-015-0131-2

Khachatryan, H., & H. J. Choi. (2017). Factors Affecting Consumer Preferences and Demand for Ornamental Plants. FE938. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe938

Krishna, R., Karkute, S. G., Ansari, W. A., Jaiswal, D. K., Verma, J. P., & Singh, M. (2019). Transgenic tomatoes for abiotic stress tolerance: status and way ahead. 3 Biotech, 9(4), 143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-019-1665-0

Lee, S., Noh, Y-H., Verma, S., & Whitaker, V. M. (2016). DNA, Technology, and Florida Strawberries. HS1287. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1287-2016

Lee, S., Yoo, C., Folta, K., & Whitaker, V. M. (2018). CRISPR Gene Editing in Strawberry. HS1315. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1315

Mendelsohn, M., Pierce, A. A., & Striegel, W. (2023). U.S. EPA oversight of pesticide traits in genetically modified plants and recent biotechnology innovation efforts. In Frontiers in Plant Science (Vol. 14). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1126006

Menz, J., Modrzejewski, D., Hartung, F., Wilhelm, R., & Sprink, T. (2020). Genome Edited Crops Touch the Market: A View on the Global Development and Regulatory Environment. In Frontiers in Plant Science (Vol. 11). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.586027

Normile, D. (2019). Gene-edited foods are safe, Japanese panel concludes. ScienceInsider. https://www.science.org/content/article/gene-edited-foods-are-safe-japanese-panel-concludes

Palangasinghe, P. C., Liyanage, W. K., Wickramasinghe, M. P., Palangasinghe, H. R., Shih, H.-C., Shiao, M.-S., & Chiang, Y.-C. (2024). Reviews on Asian citrus species: Exploring traditional uses, biochemistry, conservation, and disease resistance. Ecological Genetics and Genomics, 32, 100269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egg.2024.100269

Pothering J. (2019). Europe’s Gene Editing Regulation Exposes the Messy Relationship Between Science and Politics. AgFunder Network. https://agfundernews.com/europes-gene-editing-regulation-exposes-the-messy-relationship-between-science-and-politics

Rodríguez-Leal, D., Lemmon, Z. H., Man, J., Bartlett, M. E., & Lippman, Z. B. (2017). Engineering Quantitative Trait Variation for Crop Improvement by Genome Editing. Cell, 171(2), 470–480.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.030

Rothan, C., Diouf, I., & Causse, M. (2019). Trait discovery and editing in tomato. The Plant Journal: For Cell and Molecular Biology, 97(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14152

Sánchez-León, S., Gil-Humanes, J., Ozuna, C. V., Giménez, M. J., Sousa, C., Voytas, D. F., & Barro, F. (2018). Low-gluten, nontransgenic wheat engineered with CRISPR/Cas9. Plant biotechnology journal, 16(4), 902–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12837

Schneider, K., Goodrich-Schneider, R., & Richardson, S. (2014). Genetically Modified Food. FSHN02-2. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fs084

Stokstad, E. (2023). European Commission proposes loosening rules for gene-edited plants. In AAAS Articles DO Group. ScienceInsider. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adj6428

Stokstad, E. (2024). European Parliament votes to ease regulation of gene-edited crops. In AAAS Articles DO Group. ScienceInsider. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.zdjbra4

United States Department of Agriculture. (2018). Secretary Perdue Issues USDA Statement on plant breeding innovation | Press Release. https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2018/03/28/secretary-perdue-issues-usda-statement-plant-breeding-innovation

United States Department of Agriculture. (2020a). USDA SECURE Rule Paves Way for Agricultural innovation | Press Release. https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2020/05/14/usda-secure-rule-paves-way-agricultural-innovation

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (2020b), Part 340-Movement of Organisms Modified or Produced through Genetic Engineering. (7 CFR part 340). United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-7/subtitle-B/chapter-III/part-340?toc=1

United States Department of Agriculture. (2022). History highlight: APHIS begins overseeing AG Biotech. United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/sa_by_date/sa-2022/aphis50-hh-biotech#:~:text=APHIS’%20first%20major%20biotechnology%20regulation,used%20in%20the%20creation%20process

United States Department of Agriculture. (2023). Japan Gives Green Light to Genome Edited Waxy Corn Product. (Report JA2023-0029). United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agriculture Service. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Japan%20Gives%20Green%20Light%20to%20Genome%20Edited%20Waxy%20Corn%20Product_Tokyo_Japan_JA2023-0029.pdf

USDA-APHIS Determines that Yield10 Bioscience’s Omega-3 Camelina Varieties May Be Planted and Bred in the United States | Press Release. (2024, March 21). Yield10 Bioscience, Inc. https://www.yield10bio.com/press/usda-aphis-determines-yield10-biosciences-omega-3-camelina-varieties-planted-bred-united-states

Van Der Meer, P., Angenon, G., Bergmans, H., Buhk, H. J., Callebaut, S., Chamon, M., Eriksson, D., Gheysen, G., Harwood, W., Hundleby, P., Kearns, P., Mcloughlin, T., & Zimny, T. (2023). The Status under EU Law of Organisms Developed through Novel Genomic Techniques. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 14(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.105

Vigouroux, A., & Bikard, D. (2020). CRISPR Tools to Control Gene Expression in Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 84(2). https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00077-19

Voigt, B. (2023). EU regulation of gene-edited plants—A reform proposal. Frontiers in Genome Editing, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgeed.2023.1119442

Waltz, E. (2016). Gene-edited CRISPR mushroom escapes US regulation. Nature, 532(7599), 293. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.19754

Watson, E. (2023). ALORA reactivates dormant genes to unlock “best performing salt-tolerant rice plant in the world.” AgFunderNews. https://agfundernews.com/alora-tests-best-performing-salt-tolerant-rice-plant-in-the-world

Yield10 Bioscience Announces that the Plant Biosafety Office of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency Has Cleared Genome-Edited E3902 Camelina for Planting in Canada | Press Release. (2024). Yield10 Bioscience, Inc. https://www.yield10bio.com/press/genome-edited-e3902-camelina-cleared-planting-canada

Yield10 Bioscience Obtains Nonregulated Status for Its Novel CRISPR-Cas9 Triple Gene-Edited Camelina Plant Lines to Boost Seed Oil Content | Yield10 Bioscience, Inc. (2018). Yield10 Bioscience, Inc. https://yield10bioscienceinc.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/yield10-bioscience-obtains-nonregulated-status-its-novel-crispr

Yield10 Bioscience Receives Favorable Ruling from the Argentine Biosafety Commission (CONABIA) for Company’s Camelina Lines | Press Release. (2022). Yield10 Bioscience, Inc. https://www.yield10bio.com/press/yield10-bioscience-receives-favorable-ruling-from-the-argentine-biosafety-commission-conabia-for-companys-camelina-lines

Table 1. A selection of companies using CRISPR gene editing for crop improvement.

Table 2. Development status of various CRISPR-modified crops.