Introduction

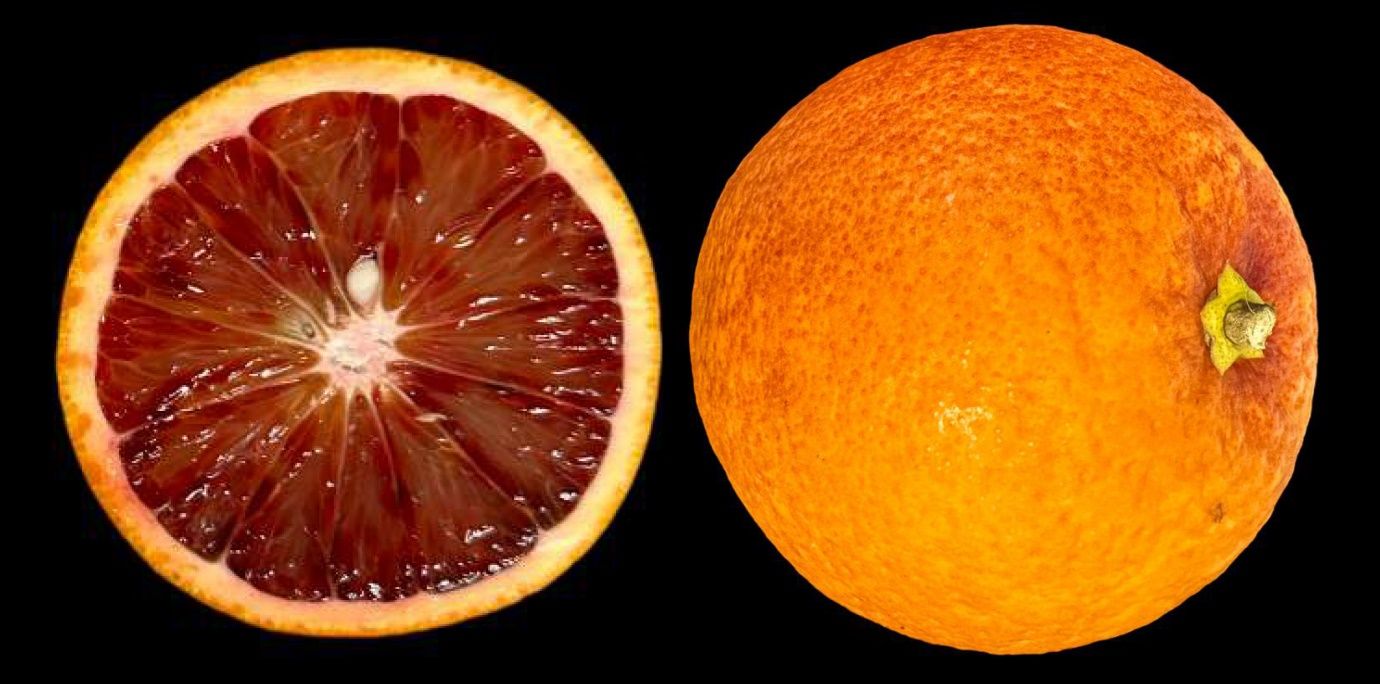

Blood orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) fruit (Figure 1) contain nutritionally beneficial compounds such as anthocyanins, flavonoids, polyphenols, hydroxycinnamic acids, and ascorbic acid, which provide various health advantages due to their antioxidant activity.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin concentration is considered an important fruit quality index for blood oranges, being responsible for the characteristic red color of the pulp and juice and closely correlated with antioxidant activity (Figure 2). Therefore, high levels of anthocyanin in blood oranges play a crucial role as a key marker for assessing fruit quality in the market and by consumers. Anthocyanin levels in blood oranges depend on multiple factors including the cultivar, cultural practices, soil characteristics, climate conditions, and harvest maturity.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Blood oranges are particularly adept at developing high levels of anthocyanin in the flesh when subjected to the marked diurnal temperature fluctuations typical of Mediterranean climates, with the low nighttime temperatures playing a crucial role in this process (Figure 3). However, commercial cultivation of blood oranges in subtropical or tropical regions, including Florida, is limited by their pale internal color and lower anthocyanin accumulation at commercial harvest maturity (Figure 4).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

This article discusses the postharvest enhancement and preservation of anthocyanin content in blood oranges grown in subtropical or tropical regions, such as Florida, for fresh consumption or for juice processing. Recent research from UF/IFAS demonstrates that storing harvested blood oranges at cold temperatures can induce postharvest anthocyanin enhancement. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to introduce growers, Extension agents, and specialists to simple postharvest methods for enhancing anthocyanin content in blood oranges, making the fruit more nutritious and more acceptable for consumption.

Anatomy of Blood Orange Fruit

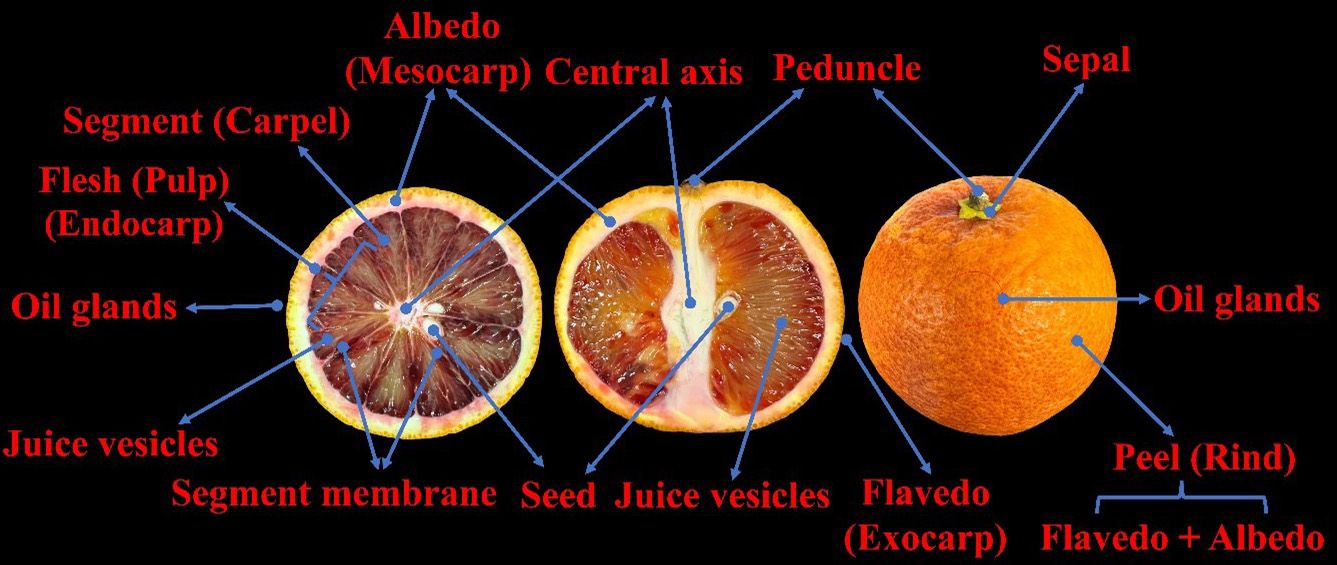

The anatomy of a blood orange fruit (Figure 5) is much like that of a regular orange, except for the presence of anthocyanin. A blood orange fruit consists of the parts listed below.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

- Peel (Rind): The outermost layer of the fruit is typically orange in color, like a regular orange, and it protects the inner parts from damage and infection. The peel of a blood orange may be orange or have a reddish blush or streaks, depending on the cultivar and the temperature during ripening.

- Flavedo: The colored outer layer of the peel, which in blood oranges can range from orange to deep red or purple, depending on the cultivar and ripeness. This layer contains the pigments responsible for the surface color of blood oranges, including the anthocyanin (red) and carotenoid (orange) pigments. The flavedo also contains oil glands that produce essential oils that contribute to the fruit’s aroma and flavor.

- Albedo: The white, spongy inner layer of the peel, which is less bitter compared to the flavedo. The albedo of a blood orange may also have some red pigmentation, especially near the edges of the segments.

- Segments (Carpels): The fleshy parts of the fruit that contain the juice and the seeds, similar to those of other citrus fruits. A blood orange usually has 10 to 12 segments, each enclosed by a thin membrane called the endocarp. The color of the segments of a blood orange depends on the amount of anthocyanin that accumulates in the flesh, and ranges from light pink to deep red. The segments are the edible part of the fruit and have a sweet and tart flavor.

- Flesh (Pulp): The soft, fleshy part of the fruit that surrounds the juice sacs. Blood orange pulp is typically juicy and has a sweet-tart flavor.

- Juice vesicles: The individual compartments within the segments that contain the juice of the fruit. In blood oranges, these juice vesicles can vary in color from orange to deep red, depending on the cultivar and the ripeness stage (Figure 6).

- Segment membranes: Thin, translucent membranes separate the segments of the fruit from each other.

- Central axis: Blood oranges, like other citrus fruits, do not have a central core. Instead, they have a central axis where the segments attach.

- Seeds: Blood oranges are typically seedless or have very few seeds per segment, depending on the cultivar and the amount of pollination. The seeds are found within the segments and are surrounded by the pulp.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin Structure

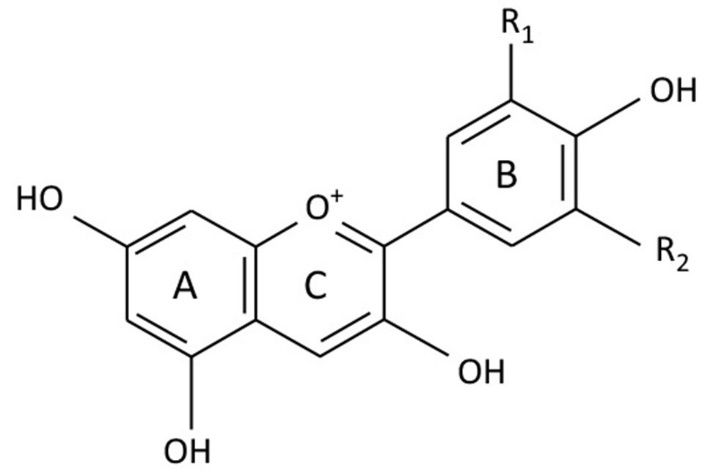

Anthocyanins are derived from anthocyanidins by adding sugars. The most common anthocyanidins include cyanidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, delphinidin, petunidin, and malvidin (Figure 7). The structure of anthocyanins consists of a flavylium cation (a positively charged ring) attached to one or more sugar molecules. The flavylium cation can have different hydroxyl and methoxyl groups, which affect the color and stability of the pigment (Table 1).

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin Profiles in Blood Oranges

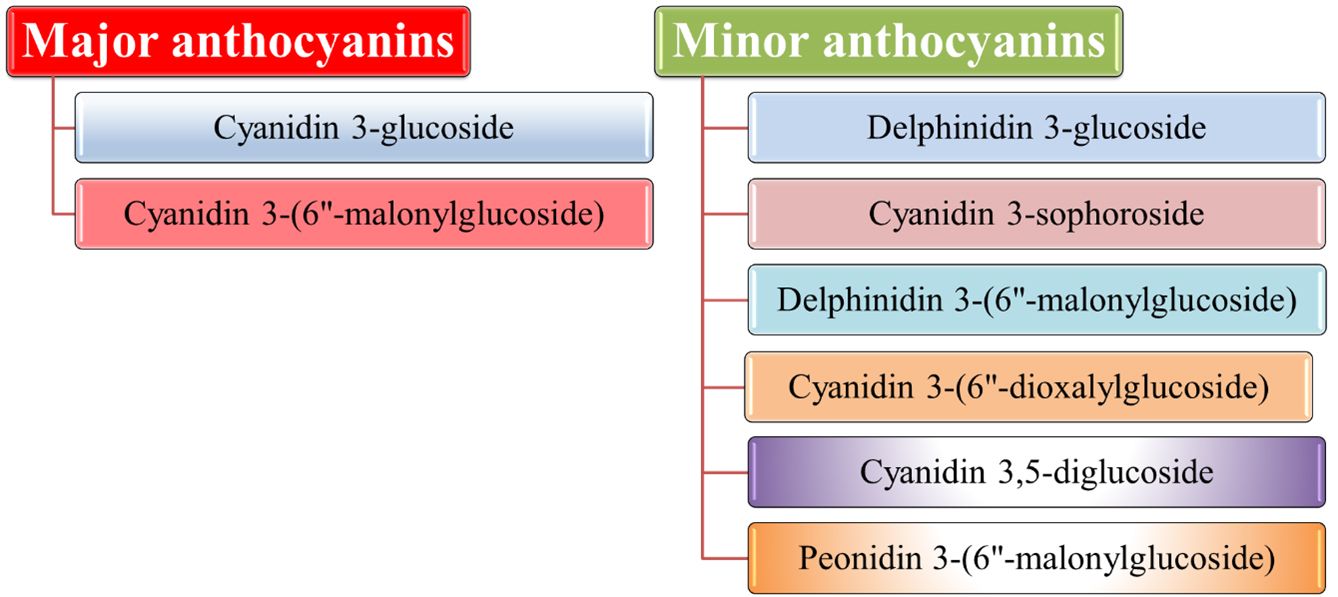

Cyanidin 3-glucoside and cyanidin 3-(6"-malonylglucoside) constitute more than 90% of the total anthocyanins in blood oranges, making them the major anthocyanins. Figure 8 displays minor individual anthocyanins alongside the major ones.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin Biosynthesis

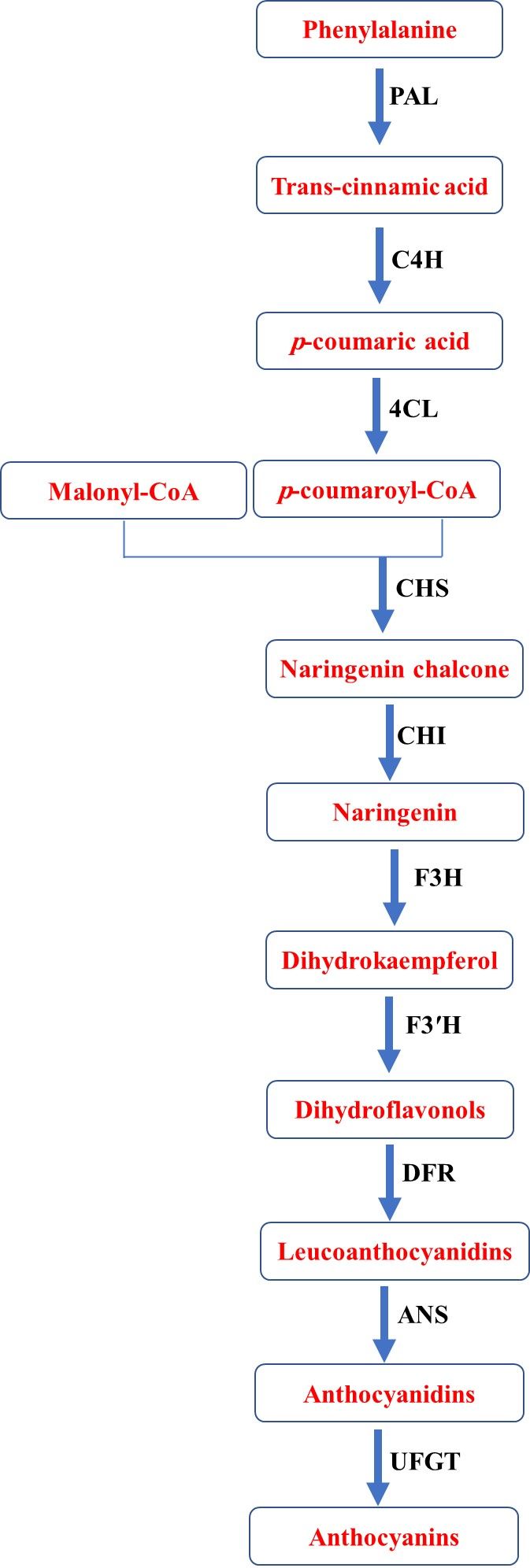

The biosynthesis of anthocyanins in blood oranges occurs through the phenylpropanoid pathway on the cytoplasmic face of the endoplasmic reticulum. This process involves the activation of multi-enzyme complexes for anthocyanin synthesis starting with the amino acid phenylalanine, which serves as the precursor for the synthesis of anthocyanidins. The phenylpropanoid pathway entails a series of reactions that are regulated by numerous enzyme complexes, including phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), and UDP-glucose-flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) (Figure 9). Finally, anthocyanidins are glycosylated by adding sugar moieties through UDP-glucose-flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) and produce anthocyanins.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin Transportation in Blood Oranges

The anthocyanins formed in the cytoplasm (as glycosylated forms of anthocyanidins) of fruit cells are transported into the cell’s vacuole through a process involving a series of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), which are regulated by the gene family encoding these enzymes (Figure 10).

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin Accumulation in Blood Oranges

The anthocyanin pigment in blood oranges begins accumulating in the vesicles at the edges of the segments (Figure 11), as well as at the blossom end of the fruit peel (Figure 12). Certain cultivars of blood oranges, like ‘Sanguinello’, are capable of synthesizing anthocyanins in their peel (Figure 13).

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Anthocyanin Degradation in Blood Oranges

The main places for anthocyanin degradation in blood oranges are cell vacuoles. Some physical and chemical factors, such as pH, temperature, oxygen availability, enzyme activity, ascorbic acid, sugars, and sugar degradation products, can affect the stability and degradation of anthocyanins. The main enzymes responsible for anthocyanin degradation in blood oranges are polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and β-glucosidase (anthocyanase). The PPO catalyzes the oxidation of anthocyanins to brown-colored compounds, while anthocyanase hydrolyzes the sugar moiety of anthocyanins, causing the molecules to lose their red color and making them more susceptible to oxidation and decolorization.

Postharvest Anthocyanin Enhancement in Blood Oranges

Storage at Low Temperatures

Blood orange fruit depend on cold to develop their internal red pigmentation. In a Mediterranean climate, cold night temperatures occur during the late fruit development period, stimulating anthocyanin synthesis. Exposure to cold temperatures postharvest (e.g., during storage) can also enhance anthocyanin synthesis and accumulation in blood oranges grown in subtropical and tropical regions that rarely experience cold nights during the critical fruit development period (Figure 14). The mechanism by which cold stress can enhance anthocyanins is through the activation of the Ruby gene, which regulates the expression of enzymes and transporters involved in anthocyanin synthesis and accumulation in the phenylpropanoid pathway.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Postharvest anthocyanin synthesis in blood oranges is greatly promoted by moderate temperatures (10°C or 12°C; 50°F or 53.6°F) during cold storage (Figure 15). Therefore, moderate temperature exposure after harvest can be used as a simple technique for enhancing anthocyanin accumulation in blood orange fruit. However, ambient temperature does not enhance postharvest anthocyanin accumulation in blood oranges (Figure 16). It should be noted that a minimum anthocyanin content and level of gene expression at harvest must exist in blood oranges for anthocyanin enhancement after harvest to be possible (Figure 17).

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Additionally, storage at very low temperatures (below 3°C, 37.4°F) inhibits anthocyanin accumulation in blood oranges (Figure 18) due to a decrease in cellular metabolism, accompanied by a downregulation of the gene transcripts involved in the metabolic pathways of anthocyanin biosynthesis. In addition, very low-temperature cold storage can also induce chilling injury, which severely reduces the fruit quality of blood oranges. The detrimental effects of chilling injury on their quality and shelf life can make blood oranges completely unmarketable. Chilling injury can cause injury symptoms on the fruit peel such as pitting, browning, and water soaking (Figure 19). Therefore, careful management of postharvest cold storage conditions is crucial to optimize anthocyanin accumulation in blood oranges while minimizing the risk of chilling injury.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

In addition, certain genetic disorders can affect pigmentation in blood orange fruit. In blood oranges, a chimera represents a genetic mutation capable of influencing anthocyanin biosynthesis both in the peel (Figure 20) and the flesh during postharvest storage (Figure 21).

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Other Postharvest Treatments

Some postharvest treatments, such as physical treatments including superatmospheric oxygen storage or chemical elicitors, can be used to enhance anthocyanin content and fruit quality. Some postharvest treatments with chemical elicitors that have been reported to be effective for blood oranges are γ-aminobutyric acid, methyl jasmonate, methyl salicylate, salicylic acid, brassinosteroids, polyamines, glycine betaine, ethylene, and nitric oxide. These treatments can increase anthocyanin concentration, antioxidant activity, and shelf life of blood oranges. However, the effects of these treatments may vary depending on the cultivar, dose, and duration. In addition, none of these experimental treatments are labeled by the U.S. EPA for application to blood oranges.

Consumption of Blood Oranges

Blood oranges can be consumed as fresh fruit, or processed into juice, wine, or dried products. Fresh fruit can be peeled and eaten as is or segmented for salads or desserts (Figures 22 and 23). Juice can be extracted from the fruit by hand or by machine and can either be consumed fresh (Figure 24) or processed into various products such as juice concentrates and flavored beverages. Dried blood orange fruit can be made by freeze-drying sliced segments. Freeze-drying removes the moisture from the fruit and extends its shelf life (Figure 25). Freeze-dried blood orange fruit is a lightweight, convenient, and high-energy snack that is easy to store, retaining its quality up to several years (Figure 26). Proper storage in a cool, dry place and in airtight containers is essential to achieve this extended shelf life. This product can be enjoyed year-round and can be added to water after crushing (Figure 27). When freeze-dried blood orange fruit is added to water, it releases the sugars, acids, pigments, and natural color compounds present in the fruit, creating a desirable and refreshing drink option. See Ask IFAS publication HS1468, “Freeze-Dried Muscadine Grape: A New Product for Health-Conscious Consumers and the Food Industry,” for more information on how to freeze-dry fruit.

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Credits: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Summary

Postharvest enhancement of anthocyanin in blood oranges is crucial for improving their internal quality, marketability, and consumer acceptance, particularly in subtropical and tropical climates where anthocyanin accumulation is limited. Storing blood oranges at moderately cold temperatures (10°C–12°C) can substantially enhance anthocyanin levels, making the fruit more appealing and nutritious. However, careful postharvest management is necessary, as very low temperatures (below 3°C) can inhibit anthocyanin accumulation and cause chilling injuries. Furthermore, other postharvest treatments, such as superatmospheric oxygen storage and chemical elicitors, can also enhance anthocyanin content. By applying these effective postharvest strategies, growers and industry specialists can overcome challenges associated with low anthocyanin synthesis and accumulation in tropical- and subtropical-grown blood oranges and produce high-quality fruit that meets consumer expectations. These approaches not only enhance fruit quality but also increase the overall competitiveness of the citrus industry in non-Mediterranean climates.

References

Carmona, L., B. Alquézar, V. V. Marques, and L. Peña. 2017. “Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Accumulation in Blood Oranges during Postharvest Storage at Different Low Temperatures.” Food Chemistry 237: 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.076

Habibi, F., M. E. García-Pastor, J. Puente-Moreno, F. Garrido-Auñón, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2023. “Anthocyanin in Blood Oranges: A Review on Postharvest Approaches for Its Enhancement and Preservation.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 63(33): 12089–12101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2098250

Habibi, F., A. Sarkhosh, J. Kim, M. Shahid, F. Gmitter, and J. Brecht. 2023. “Citrus Fruit Pigments: HS1472, 11/2023.” EDIS 2023(6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-HS1472-2023

Habibi, F., M. A. Shahid, R. L. Spicer, C. Voiniciuc, J. Kim, F. G. Gmitter, J. K. Brecht, and A. Sarkhosh. 2024. “Postharvest storage temperature strategies affect anthocyanin levels, total phenolic content, antioxidant activity, chemical attributes of juice, and physical qualities of blood orange fruit.” Food Chemistry Advances 4: 100722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2024.100722

Hillebrand, S., M. Schwarz, and P. Winterhalter. 2004. “Characterization of Anthocyanins and Pyranoanthocyanins from Blood Orange [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck] Juice.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 52(24): 7331–7338. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0487957

Kırca, A., and B. Cemeroğlu. 2003. “Degradation Kinetics of Anthocyanins in Blood Orange Juice and Concentrate.” Food Chemistry 81(4): 583–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00500-9

Sarkhosh, A., F. Habibi, and S. A. Sargent. 2023. “Freeze-Dried Muscadine Grape: A New Product for Health-Conscious Consumers and the Food Industry: HS1468, 7/2023.” EDIS 2023(4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-HS1468-2023

Sarkhosh, A., F. Habibi, S. A. Sargent, and J. K. Brecht. 2023. “Freeze-drying does not affect bioactive compound contents and antioxidant activity of muscadine fruit.” Food and Bioprocess Technology 17: 2735–2744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-023-03277-w