Seed-Borne Diseases on Okra

Okra is an important specialty vegetable grown in Florida, particularly in south Florida, during the summer when many other crops struggle with heat stress. As consumer interest in okra continues to rise, largely due to its nutritional and medicinal value, more growers will develop an interest in growing this crop in Florida. However, diseases caused by seed-borne pathogens have emerged as a challenge in okra production. Growers in south Florida have reported frequent issues with poor seedling establishment, often linked to Rhizoctonia damping-off, a disease transmitted through contaminated seeds and soil that can lead to serious yield losses. In addition to Rhizoctonia, okra is susceptible to a wide range of seed-borne fungi and bacteria (Table 1), which can cause significant yield losses and reduced quality. South Florida’s subtropical climate, having high humidity and warm temperatures, makes the situation even worse by allowing diseases to develop quickly.

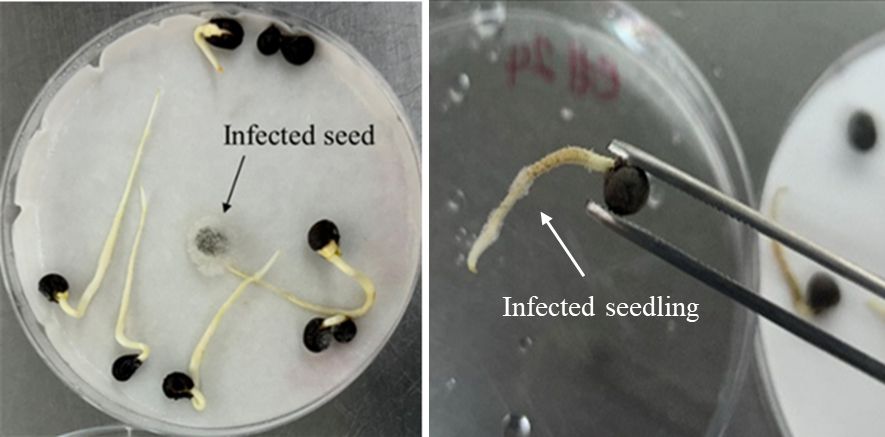

Seed-borne pathogens can reside on or within the seeds (either beneath the seed coat or within the embryo) (Dell'Olmo et al. 2023; Dolezal et al. 2014), remaining dormant until favorable conditions exist, and then leading to seed rot or inhibition of seedling development (Figure 1). Hamim et al. (2014) found that okra seeds naturally contaminated with fungal pathogens such as Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium spp., and Colletotrichum dematium exhibited germination failure rates of up to 50.5%. Additionally, Rani et al. (2021) conducted artificial inoculation experiments on okra seeds with various seed-borne pathogens and reported a germination reduction ranging from 17% to 39%, depending on the specific pathogen and inoculum concentration.

Many seed-borne pathogens have a broad host range. For instance, Fusarium oxysporum (causing Fusarium wilt and seed decay) is among the most significant phytopathogenic fungi infecting almost 150 plant species, including economically important vegetables, fruit trees, and ornamentals (Rana et al. 2017). A host-specific strain, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum, has been known to affect cotton for decades in the United States and was more recently reported on okra (Keinath et al. 2023). Infected okra seeds can carry these pathogens and spread them to new locations, posing a risk to other locally grown, economically important crops.

Moreover, our lab found that even seeds purchased from certified US seed vendors can carry harmful pathogens, like Macrophomina phaseolina. This is because there are currently no national, crop-specific regulatory or certification programs targeting pathogens in okra seeds. Most commercial okra seeds are produced under general good agricultural practices (GAPs), and while some producers may follow broader certification programs, like those from the Association of Official Seed Certifying Agencies (AOSCA), these mainly focus on genetic purity, germination, and weed contamination, rather than disease prevention. Additionally, many small-scale growers save seeds from their own plants. If those plants are infected, the saved seeds can introduce pathogens into new fields.

To support better on-farm decision-making, this publication provides guidance on effective management strategies for seed-borne diseases in okra. This resource is designed for commercial growers, agricultural consultants, farm managers, Extension agents and specialists, and anyone interested in vegetable production and sustainable farming practices.

Credit: Monalisa Seaton, UF/IFAS

Effective Disease Control and Management Strategies

To mitigate the impact of seed-borne diseases on okra production, three major approaches, consisting of cultural, biological, and chemical, are commonly used. Among these, the most familiar approach to us is chemical control, involving synthetic chemicals (e.g., fungicides and bactericides), which have been widely used for decades as a cost-effective solution for controlling seed-borne diseases. However, alternative methods are increasingly needed due to pathogen resistance to fungicides, environmental concerns, and the growing market for organic crops. Cultural practices (such as using certified clean seeds, disease-resistant cultivars, and crop rotation) aim to reduce crop susceptibility to diseases by making them less available, less attractive, and less vulnerable to pathogens or by creating conditions that promote plant growth while inhibiting disease development. Biological control is an environmentally friendly and sustainable strategy that uses a pathogen’s natural enemies to reduce populations of "bad microbes." Many biological products are available on the market, though maintaining their effectiveness and consistency can be challenging since environmental conditions and pathogen dynamics vary.

Integrated pest management (IPM), which utilizes a combination of cultural, biological, and chemical control methods, is highly recommended to reduce reliance on a single approach and help achieve long-term and effective disease control, ensuring healthier crops and more sustainable crop production. The following sections summarize these preventative/control strategies for okra seed-borne diseases.

Cultural Control

Avoid planting okra in areas with a history of disease and ensure soil temperatures are between 77°F and 95°F (25°C and 35°C) at planting. Rapid germination occurs around 95°F (35°C), while temperatures below 62.6°F (17°C) prevent seeds from germinating (Singh and Gupta 2020). Rapid germination and emergence can minimize seed infection from seed- or soil-borne pathogens by reducing the time seeds remain vulnerable in the soil. Many seed-borne pathogens, such as Phytophthora nicotianae, thrive in cool to warm (68°F–86°F [20°C–30°C]) and moist soils (Matny 2013); therefore, proper timing of planting and avoiding over-irrigation are essential for preventing seed-borne diseases. Additionally, close plant spacing can create a humid microclimate with reduced air circulation, promoting pathogen growth. It is recommended to space okra plants with 36–60 inches between rows, 4–10 inches between seeds, and a planting depth of 0.5–1.0 inches, resulting in a plant population of approximately 43,560 per acre (Seal et al. 2023).

Avoid planting okra in fields previously used for crops in the mallow family, Malvaceae (such as cotton and hibiscus), or crops susceptible to similar diseases, like cucumbers, melons, squash, beans, and peas. Rotating with crops such as maize, cowpea, and radish can help disrupt the pathogen life cycle and reduce pathogen populations (Sharma and Kumar 2004). Additionally, it is essential to remove and destroy any infected plant debris in the early stages of disease appearance to prevent further spread.

Currently, there are few okra varieties in the United States with resistance to seed-borne diseases, highlighting the need for focused breeding efforts on okra. However, Brazilian accessions like ‘BR-2399’, ‘BR-1449’, and ‘Santa Cruz-47’ have shown resistance to Fusarium wilt (caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum), while ‘Santa Cruz-47’ has also shown resistance to Verticillium wilt (caused by Verticillium dahlia) (Aguiar et al. 2013). In major okra-growing countries like India, varieties such as ‘IC-90293’, ‘V4680’, ‘V-4365’, and ‘IC-42495B’ demonstrate resistance to root rot caused by Fusarium solani (Kumari et al. 2019).

When harvesting, avoid collecting seeds from diseased plants because infected plants can transmit seed-borne pathogens to their seeds. These pathogens may remain viable on or within the seeds, persisting through storage and leading to new infections in young plants. Store seeds at 35°F–40°F (2°C–4°C) with humidity below 40% to prevent seed aging and decay (Bayer Group 2020). If using a refrigerator, keep seeds in a tightly sealed container to maintain low humidity. Before planting, soak the seeds in hot water at 125.6°F (52°C) for 12–15 minutes to help reduce pathogen populations (Abduhu et al. 2018).

Biological Control

Plant-based treatments, such as extracts from neem leaves, garlic, and allamanda, have historically been recommended for controlling seed-borne pathogens (Saha et al. 2014). For example, garlic extract suspensions have been shown to improve crop quality and soil conditions as a result of garlic’s strong antibacterial, antifungal, and allelopathic characteristics (Hayat et al. 2022). Garlic contains allicin, a compound with potent antimicrobial properties that can reduce seed-borne diseases like rot, wilting, or mold, caused by several pathogens such as Macrophomina phaseolina, Aspergillus spp., Colletotrichum dematium, Fusarium oxysporium, and Fusarium moniliforme (Hayat et al. 2022; Saha et al. 2014).

Bio-priming is a seed treatment method that uses beneficial microbes like Trichoderma harzianum, T. koningii, Gliocladium virens, Paecilomyces lilacinus, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Bacillus subtilis, Rhizobium meliloti, and Streptomyces species (Reddy 2012; Kumar 2019). These microbes can help control root rot and reduce infections caused by fungal pathogens, such as M. phaseolina, R. solani, and Fusarium species. For example, here are some steps for seed treatment with biological agents (Reddy 2012):

- Soak the seeds in clean water for 12 hours.

- Mix the soaked seeds with the bioagent product (like Trichoderma harzianum), following the label instructions.

- Pile the seeds together and cover them with a damp cloth, plastic bag, or sack to retain moisture.

- Keep the seeds in a warm, humid place (around 77°F–90°F [25°C–32°C]) for about 2 days (48 hours) to let the treatment take effect.

- Sow the bio-primed seeds in the field for growth.

Furthermore, some biological agents have been studied as seed treatments to control seed-borne bacteria. For example, Bacillus velezensis strain 71 and Paenibacillus peoriae strain To99 were reported to be effective against Xanthomonas spp., which cause bacterial blight. Their effectiveness comes from producing compounds like oxydifficidin (B. velezensis 71) and polymyxin A (P. peoriae To99), which inhibit the growth of Xanthomonas (Olishevska et al. 2023; Taghavi et al. 2018). To manage these bacteria, treat okra seed with a liquid suspension or apply a soil drench to the planting area before sowing (Taghavi et al. 2018).

Chemical Control

Many synthetic fungicides and bactericides are registered for preventing and controlling seed-borne diseases in okra using various application methods (see Table 2). These include seed treatments, which involve coating or soaking seeds in chemical solutions before planting to eliminate or suppress pathogens on the seed surface or within the seed coat. Use soil applications, such as drenches or granules, to target pathogens that persist in the soil and infect seedlings after germination. Apply foliar sprays or systemic treatments to young plants once symptoms appear to limit disease spread and reduce further infection. The choice of application method depends on the pathogen involved, the timing of infection, and the severity of the disease.

Chemical management is considered unsustainable due to resistance risks and should be a last resort after cultural and biological controls. Always use personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gloves, masks, goggles, and protective clothing, to ensure safety during chemical handling and application (Figure 2). Store chemicals in a cool, dry, and well-ventilated area, away from food, water sources, and direct sunlight, to prevent contamination or degradation. Educate employees about proper handling, storage, and disposal procedures to reduce risks and ensure safe use. Follow manufacturer-recommended application rates and safety precautions to achieve optimal results. Note that overuse or misuse of chemicals can harm plants, humans, and beneficial organisms while increasing the risk of environmental pollution. Growers may unintentionally overuse chemicals if different products contain the same active ingredient, so it is essential to check the labels carefully when planning chemical applications.

Finally, addressing seed-borne diseases in okra is a complex challenge that demands extensive research and innovation. Key areas of focus include developing disease-resistant varieties, establishing national programs for certified clean seeds, improving sustainable field practices, identifying effective biological agents, and expanding the availability of chemical treatment options specifically labeled for okra in Florida. These efforts are vital for minimizing the risk of seed-borne infections, breaking disease cycles in new plantings, and safeguarding both crop productivity and economic stability.

Credit: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS

Table 1. Seed-Borne Pathogens and Associated Diseases Reported in Okra

Table 2. Pesticides Registered for Seed-Borne Disease Control in Okra

Sources: Mishra et al. (2022); Seal et al. (2023); Khare et al. (2015); EPA (2023)

Summary

Seed-borne diseases pose a significant threat to the productivity and quality of okra, impacting both economic stability and food safety. Effective control strategies are vital for mitigating these risks and ensuring sustainable okra production. By adopting integrated management practices that include rigorous seed treatment, the use of resistant varieties, and crop rotation, growers can minimize the impact of seed-borne pathogens. The following steps summarize how to manage seed-borne diseases:

Step 1: Start with clean seeds.

- Always use high-quality, certified seeds from trusted sources.

- Store seeds in sealed bags (like paper, cloth, or plastic) in a cool, dry place.

- For better results, use fresh seeds each season to reduce the risk of poor germination or seed-borne disease.

Step 2: Use good planting practices.

- Plant during peak seasons in well-drained soil.

- Rotate okra with other crops and avoid planting okra in the same spot for at least three years. This helps break the disease life cycles and prevents the buildup of soil-borne pathogens

Step 3: Focus on cultural controls first.

- Remove any infected plants or debris as soon as you see them.

- Avoid watering in the late afternoon or evening to keep humidity down.

Step 4: Use biological seed treatments as preventative measures.

- Before planting, treat seeds with helpful microbes like Trichoderma or Bacillus to stimulate plant growth and protect against disease.

Step 5: Use chemicals only if necessary.

- Use fungicide-treated seeds if your field has a history of disease problems.

- If you notice early signs of disease (like damping-off or poor seedling health), apply recommended fungicides in time. Always rotate products and follow the label instructions to avoid chemical resistance and protect your crop safely.

References

Abduhu, M., A. A. Khan, I. H. Mian, M. A. K. Mian, and M. Z. Alam. 2018. “Effect of Seed Treatment with Sodium Hypochlorite and Hot Water on Seed-Borne Fungi and Germination of Okra Seed.” Journal of Experimental Agriculture International 22 (2): 41–50.

Aguiar, F. M., S. J. Michereff, L. S. Boiteux, and A. Reis. 2013. “Search for Sources of Resistance to Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum) in Okra Germplasm.” Crop Breeding and Applied Biotechnology 13 (1): 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1984-70332013000100004

Aravind, T., and A. B. Brahmbhatt. 2018. “Protein Profiling of Okra Genotypes Resistant to Root and Collar Rot Incited by Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid. Using SDS-PAGE.” International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 7 (11): 2290–2293. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.711.257

Bayer Group. 2020. “Agronomic Spotlight: Vegetable Seed Storage and Handling.” Vegetables Canada. https://www.vegetables.bayer.com/ca/en-ca/resources/agronomic-spotlights/vegetable-seed-storage-and-handling.html

Dell'Olmo, E., A. Tiberini, and L. Sigillo. 2023. “Leguminous Seedborne Pathogens: Seed Health and Sustainable Crop Management.” Plants 12 (10): 2040. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12102040

Dolezal, A. L., X. Shu, G. R. OBrian, et al. 2014. “Aspergillus flavus Infection induces transcriptional and physical changes in developing maize kernels.” Frontiers in Microbiology 5: 384. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00384

EPA. 2023. Labeling Notification per Pesticide Registration (PRN) 98-10—Adding/Deleting Alternative Brand Names and Revising Warranty Statement: PFS516 Systemic Fungicide Bactericide. Written March 30, 2025. https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/ppls/073806-00003-20230330.pdf

Hamim, I., D. C. Mohanto, M. A. Sarker, and M. A. Ali. 2014. “Effect of Seed-Borne Pathogens on Germination of Some Vegetable Seeds.” Journal of Phytopathology and Pest Management 1 (1): 34–51.

Hayat, S., A. Ahmad, H. Ahmad, K. Hayat, M. A. Khan, and T. Runan. 2022. “Garlic, From Medicinal Herb to Possible Plant Bioprotectant: A Review.” Scientia Horticulturae 304: 111296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111296

Isakeit, T. 2020. “Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (Fusarium wilt).” CABI Compendium. https://doi.org/10.1079/cabicompendium.24715

Keinath, A. P., G. Rennberger, V. DuBose, S. H. Zardus, and P. A. Rollins. 2023. “Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum Identified on Okra in South Carolina, United States.” Plant Health Progress 24 (1): 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHP-05-22-0048-BR

Khare, C. P., S. Nema, J. N. Srivastava, V. K. Yadav, and N. D. Sharma. 2015. “Fungal Diseases of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) and Their Integrated Management (IDM).” In Recent Advances in the Diagnosis and Management of Plant Diseases, edited by L. P. Awasthi. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2571-3_8

Kida, K., M. Tojo, K. Yano, and S. Kotani. 2007. “First Report of Pythium ultimum var. ultimum Causing Damping‐Off on Okra in Japan.” Plant Pathology 56 (6): 1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2007.01634.x

Kumar, A. S., K. E. A. Aiyanathan, S. Nakkeeran, and S. Manickam. 2018. “Documentation of Virulence and Races of Xanthomonas citri pv. malvacearum in India and Its Correlation with Genetic Diversity Revealed by Repetitive Elements (REP, ERIC, and BOX) and ISSR Markers.” 3 Biotech 8 (11): 479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1503-9

Kumar, S. D. 2019. “Enumerations on Seed-Borne and Post-Harvest Microflora Associated with Okra [Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench] and Their Management.” GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences 08 (02): 119–130. https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2019.8.2.0149

Kumari, M., P. Naresh, and H. S. Singh. 2019. “Utilization of Wild Species for Biotic Stress Breeding in Okra: A Review.” Advance in Plants Agriculture Research 9 (2): 337–340.

Li, B. J., Y. M. Guo, and A. L. Chai. 2015. “First Report of Fusarium solani Causing Fusarium Root Rot on Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) in China.” Plant Disease 100 (2): 526. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-05-15-0588-PDN

Matny, O. N. 2013. “First Report of Damping-Off of Okra Caused by Phytophthora nicotianae in Iraq.” Plant Disease 97 (4): 558. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-08-12-0735-PDN

Mishra, P. K., A. Kumar, P. Kumar, M. Kumar, and R. Mishra. 2022. “Major Insect-Pests and Diseases of Okra and Their Management.” In Modern Perspectives in Agricultural and Allied Science. Integrated Publications. https://doi.org/10.22271/int.book.174

Okigbo, R.N., and C. M. Anene. 2017. “Prevalence of Aflatoxin in Dried Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and Tomatoes (Lycoperisicon esculentum) Commercialized in Ibadan Metropolis.” Integrative Food, Nutrition and Metabolism 5 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.15761/ifnm.10002

Olishevska, S., A. Nickzad, C. Restieri, et al. 2023. “Bacillus velezensis and Paenibacillus peoriae Strains Effective as Biocontrol Agents Against Xanthomonas Bacterial Spot.” Applied Microbiology 3 (3): 1101–1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol3030076

Quesada-Ocampo, L. M., C. H. Parada-Rojas, Z. Hansen, et al. 2023. “Phytophthora Capsici: Recent Progress on Fundamental Biology and Disease Management 100 Years After Its Description.” Annual Review of Phytopathology 61: 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-021622-103801

Rana, A., M. Sahgal, and B. N. Johri. 2017. “Fusarium oxysporum: Genomics, Diversity and Plant–Host Interaction.” In Developments in Fungal Biology and Applied Mycology, edited by T. Satyanarayana, S. K. Deshmukh, and B. N. Johri. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4768-8_10

Rani, P., A. Singh, and A. Kumar. 2021. “The Effect on Okra Seed Germination Using Filtrates of Isolated Pathogenic Fungi from Black Point Infected Wheat Grains.” Biological Forum 13 (3a): 436–440.

Reddy, P. P. 2012. “Bio-Priming of Seeds.” In Recent Advances in Crop Protection, edited by P. P. Reddy. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-0723-8_6

Saha, S., M. Khokon, and M. Hossain. 2014. “Effects of Plant Extracts on Controlling Seed Borne Fungi of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench).” Journal of Environmental Science and Natural Resources 7 (2): 85–88.

Seal, D. R., Q. Wang, R. Kanissery, et al. (2023) 2024. “Chapter 10. Minor Vegetable Crop Production: VPH ch. 10, CV294, rev. 6/2024.” EDIS (VPH). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv294-2023

Sharma, J. P., and S. Kumar. 2004. “Effect of Crop Rotation on Population Dynamics of Ralstonia solanacearum in Tomato Wilt Sick Soil.” Indian Phytopath 57 (1): 80–81. https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/IPPJ/article/view/17629

Shi, Y., X. Zhang, Q. Zhao, and B. Li. 2019. “First Report of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Causing Anthracnose on Okra in China.” Plant Disease 103 (5): 1023. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-05-18-0878-PDN

Singh, A. K., and S. Gupta. 2020. “Origin, Production, Varieties, Package of Practices for Okra.” Agriculture and Food e-Newsletter 2 (2): 100–102.

Singh, P., A. B. Abidi, V. Chauhan, and S. B. Ahmad. 2014. “An Overview of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and Its Importance as a Nutritive Vegetable in the World.” International Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences 4 (2): 227–233.

Taghavi, S., D. Van Der Lelie, J. Lee, and A. Devine. 2018. Bacillus velezensis RTI301 Compositions and Methods of Use for Benefiting Plant Growth and Treating Plant Disease. US Patent Application No. US20180020676A1, published January 25, 2018. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20180020676A1/en

Thippeswamy, B., H. V. Sowmya, B. Ramalingappa, and M. Krishnappa. 2011. “Location and Transmission of Macrophomina phaseolina and Alternaria alternata in Okra.” International Journal of Plant Protection 4 (1): 23–26.

Ziedan, E. S., and E. S. Hussein. 2012. “First Report of Alternaria Pod Blight of Okra in Egypt.” International Journal of Agricultural Technology 8 (7): 2239–2243.