Credit: Babu Panthi, UF/IFAS

Chilli thrips, (Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood; Thysanoptera: Thripidae), is an economically important pest of vegetable, fruit, and ornamental crops throughout Asia, Africa, Oceania, the Caribbean and some parts of South America and is an invasive pest in several US states (Figure 1) (Kumar et al. 2013). Chilli thrips were first observed in Florida in 1991 and again in 1994, with the first established population reported in October 2005 on roses in Palm Beach County. It was first recorded in blueberries in Hernando, Pasco, and Sumter counties in July of 2008 (Liburd personal com) and has been reported on 61 different plant species in Florida through 2011. Chilli thrips typically appear feeding on the new vegetative growth of blueberry after summer pruning.

Description and Life Cycle

Chilli thrips adults are small (1–2 mm or < 1/16 inch in length) and ¾ size of flower thrips (Figure 2) (Kumar et al. 2011). Chilli thrips adults have pale yellow bodies with dark fringed wings and dark brown incomplete stripes on the abdomen. The head is wider than it is long, and its antennae have eight segments; the first two basal segments are pale in color and the other six segments are darker.

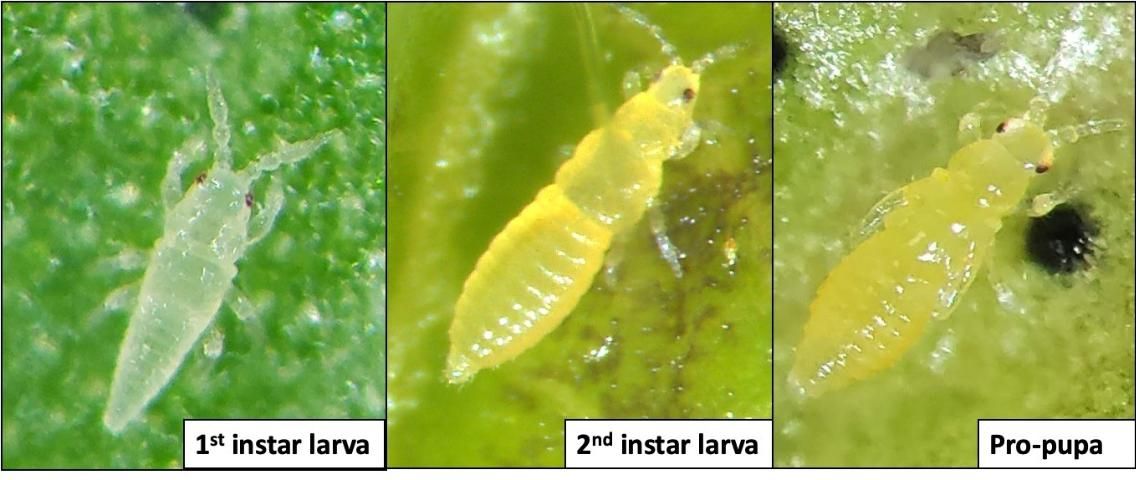

The lifecycle of chilli thrips (i.e., egg to adult) is short and typically lasts about 18–20 days at 77–81°F (25–27°C) (Kang et al. 2015). It has four life stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult (Figure 3). Female chilli thrips oviposit a single kidney-shaped egg into soft plant tissues using a sharp ovipositor. An adult female can lay around 60 eggs in its lifetime (Tatara 1995). Eggs usually hatch in 5–8 days. Two actively feeding larval instars complete their life stages in 8–10 days. The first instar larva is transparent and less than 1 mm long, while the second instar is pale yellow in color with a bowed-out abdomen (1 mm long). Two non-feeding pupal instars (pro-pupa and pupa) complete their life stages in 2–4 days. Pupation may occur on the underside of leaves, in leaf litter, in leaf curls, or in soil. Adults live for 20–25 days at 77°F (25°C).

Chilli thrips are not strong fliers and disperse over short distances using their fringed wings. Chilli thrips initially form "hot spots" in the fields, and when the amount and quality of foliage diminish, they move to adjacent plants within the field (Arévalo and Liburd 2007). Heavy infestations of chilli thrips may occur during prolonged hot and dry periods (June through September) in blueberry.

Credit: Babu Panthi, UF/IFAS

Credit: Babu Panthi, UF/IFAS

Damage

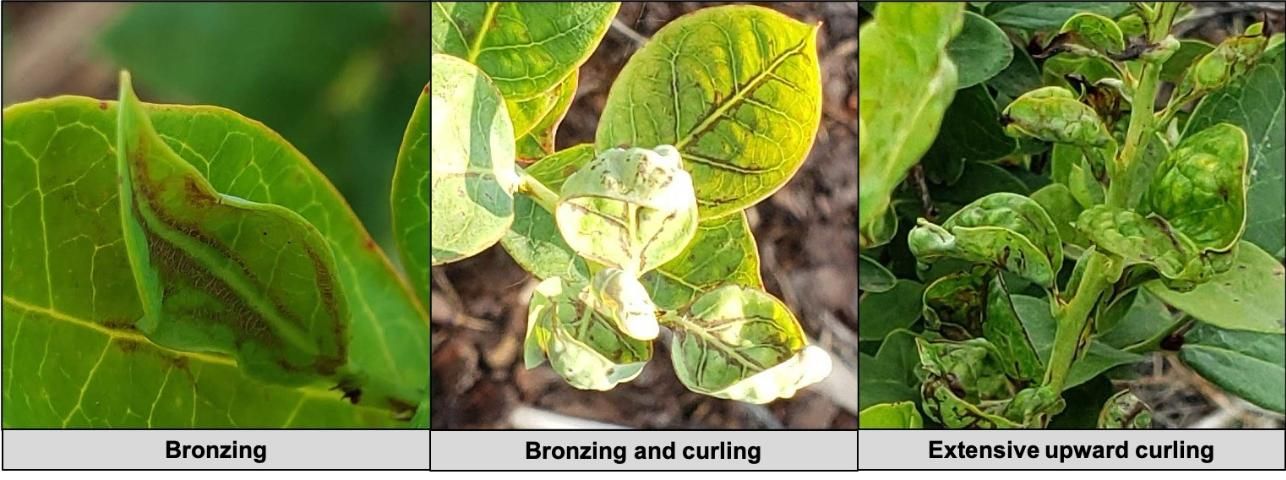

Chilli thrips feed primarily on young blueberry foliage during summer and early fall (usually beginning in late June with the first post-pruning foliar flush). Adults and larvae use mandibles to punch holes through epidermis cells and insert a maxillary stylet to remove the cellular contents of mesophyll tissues, leading to necrosis and death of tissues. Injury symptoms first appear as bronzing along leaf veins and petioles, and gradually leaves start to curl and distort (Figure 4). Heavy infestations cause leaf defoliation with extensive curling of leaves. Chilli thrips is one of 14 thrips species in the family Thripidae capable of transmitting tospoviruses. However, there are no reports of virus transmission by chilli thrips in blueberry or other crops in Florida.

Credit: Babu Panthi

Management and Control

Early detection is essential for effective chilli thrips control. The appearance of bronzing on new flush may be the first indication of the chilli thrips presence in blueberry fields. Chilli thrips tend to have an irregular and aggregated distribution within a field (Seal et al. 2006), so enough samples should be collected to accurately estimate its population in the field. Scouting or monitoring of adults can be done by observing young leaves with a 10X hand lens, tapping young foliage onto a white sheet of paper, or using white or yellow sticky cards.

An integrated management plan to control chilli thrips includes cultural, biological, and chemical controls. Cultural control consists of eliminating host plants (including weeds) in or near production fields that support the growth and development of chilli thrips. Natural predators can also be part of an integrated management program. Natural enemies such as Orius insidiosus (the minute pirate bug, which feeds on all life stages of thrips), Amblyseius swirskii (predatory mites), and Geocoris spp. (big-eyed bugs) have shown some effectiveness in managing chilli thrips populations (Arthurs et al. 2009, Dogramaci et al. 2011).

Chemical insecticides are the primary means to manage chilli thrips populations in blueberry. Reduced-risk insecticides registered for controlling chilli thrips in blueberry are spinetoram (Delegate®), tolfenpyrad (Apta®), cyantraniliprole (Exirel®), novaluron (Rimon®), acetamiprid (Assail®), and flupyradifurone (Sivanto®). Spinosad (Entrust®) can be used to manage this pest in organic blueberry production. In a recent field trial, spinetoram and tolfenpyrad were the most effective of the insecticides evaluated. Spinetoram has systemic and translaminar activity, allowing the chemical to be absorbed into plant tissues relatively quickly, and has been shown to be effective in controlling all of the life stages of chilli thrips, including egg when mixed with novaluron, an insect-growth regulator which also affects egg development. A list of products registered for managing chilli thrips in Florida blueberries along with their active ingredients and insecticide classes is provided in Table 1. Be sure to follow all insecticide label instructions, including rotating appropriate products with different modes of action to help minimize the development of insecticide resistance.

Table 1. lists registered pesticides that should be integrated with other pest-management methods. Additional information on integrated pest management methods can be requested from UF/IFAS Extension horticulture or agriculture Extension agents. A list of local UF/IFAS Extension county offices is at available at https://ifas.ufl.edu/.

References

Arévalo, H. A., and O. E. Liburd. 2007. "Horizontal and Vertical Distribution of Flower Thrips in Southern Highbush and Rabbiteye Blueberry Plantings, with Notes on a New Sampling Method for Thrips inside Blueberry Flowers." J Econ Entomol. 100:1622–1632.

Arthurs, S., C. L. McKenzie, J. Chen, M. Dogramaci, M. Brennan, K. Houben, and L. Osborne. 2009. "Evaluation of Neoseiulus cucumeris and Amblyseius swirskii (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as Biological Control Agents of Chilli Thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on Pepper." Biological Control. 49:91–96.

Dogramaci, M., S. P. Arthurs, J. Chen, C. McKenzie, F. Irrizary, and L. Osborne. 2011. "Management of Chilli Thrips Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on Peppers by Amblyseius swirskii (Acari: Phytoseiidae) and Orius insidiosus (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae)." Biological Control. 59:340–347.

Kang, S. H., J.-H. Lee, and D.-S. Kim. 2015. "Temperature-Dependent Fecundity of Overwintered Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and Its Oviposition Model with Field Validation." Pest Management Science. 71:1441–1451.

Kumar, V., G. Kakkar, C. L. McKenzie, D. R. Seal, and L. S. Osborne. 2013. "An Overview of Chilli Thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) Biology, Distribution and Management." IntechOpen.

Kumar, V., D. R. Seal, D. J. Schuster, C. McKenzie, L. S. Osborne, J. Maruniak, and S. Zhang. 2011. "Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae): Scanning Electron Micrographs of Key Taxonomic Traits and a Preliminary Morphometric Analysis of the General Morphology of Populations of Different Continents." Florida Entomologist. 94:941–955.

Panthi, B., and J. Renkema. 2020. "Managing Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Florida Strawberry with Flupyradifurone." International Journal of Fruit Science. 0:1–11.

Seal, D. R., M. A. Ciomperlik, M. L. Richards, and W. Klassen. 2006. "Distribution of Chilli Thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), in Pepper Fields and Pepper Plants on St. Vincent." Florida Entomologist. 89:311–320.

Tatara, A. 1995. "Bionomics, Monitoring and Control of Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood (Yellow Tea Thrips) in Citrus Groves." Special Bulletin of the Shizuoka Prefectural Citrus Experiment Station (Japan).