The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

This article describes the identification, biology, and importance of the American sand wasps (Bembix americana Fabricius), which are a subspecies-complex of large, robust wasps in the subfamily Bembicinae (Figure 1). The genus, Bembix, includes over 300 species of ground-nesting wasps distributed around the globe (Frank 2022). They nest gregariously in bare soil and provision their nests with flies (order Diptera). The females are progressive provisioners, meaning they continue to provide their developing larvae with prey until the larvae pupate. Males participate in a distinctive mating behavior called a “sun dance” in which groups of males fly low over nesting areas waiting for females to emerge so they can be the first to mate with them. Adults feed on flower nectar and can often be found visiting a variety of wildflowers. This species has a broad ecological range and can be found nesting in a variety of soil types and habitats, although it prefers open sandy soils (Alcock 1972; Evans 1970; Evans and Matthews 1968; Frank 2022).

Credit: Marirose Kuhlman, UF/IFAS

Synonymy

Bembix muscicapa Handlirsch, 1893

Bembix seperanda Handlirsch, 1893

Bembix foxi J. Parker, 1917

Epibembix foxi (J. Parker, 1917)

Bembix americana Fabricius, 1793

Subspecies

Bembix americana americana Fabricius, 1793

Bembix americana antilleana Evans and Matthews, 1968

Bembix americana comata J. Parker, 1917

Bembix americana dugi Menke, 1985

Bembix americana hamata C. Fox, 1923

Bembix americana nicolai Cockerell, 1938

Bembix americana spinolae Lapeletier, 1845 – sand wasp

Retrieved [Sept 21, 2021], from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System online database, http://www.itis.gov

Distribution

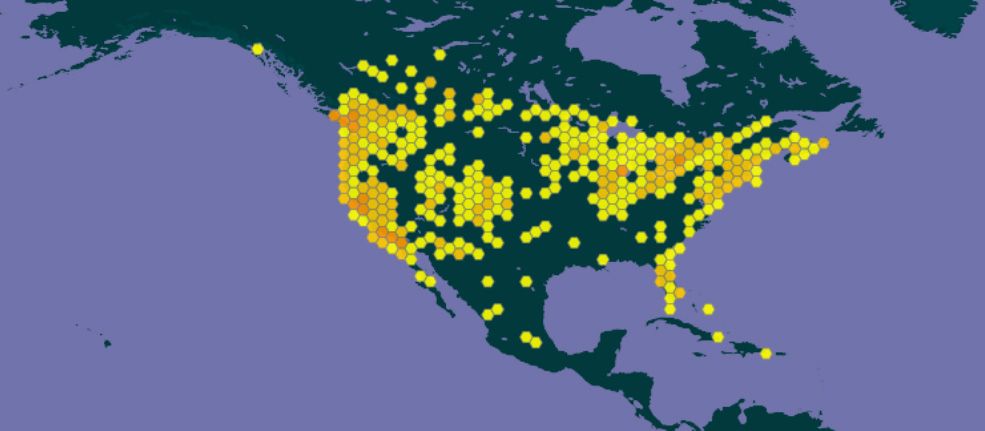

Bembix americana is found in North America throughout the United States, southern Canada, Mexico, Cuba, and the Caribbean Islands (Figure 2).

Credit: Map by GBIF, https://www.gbif.org/species/7625118, accessed February 2024

Description

American sand wasps (Figure 3) are medium-large, robust wasps about 16–20 mm long. They are mostly black with five pairs of white spots forming interrupted white bands across the abdomen. The prominent compound eyes are green, and they have three simple eyes called “ocelli”. The head and thorax are covered in short, white hairs. Their wings are clear with brown veins. The long, triangular labrum allows them to access a variety of flowers for nectar. The legs are mostly yellow.

Credit: Seth Ausubel, used with permission

Behavior

Most studies of this species and others in the genus, Bembix, focus on the complex nesting and foraging behaviors that they exhibit (Frank 2022). American sand wasps spend most of their adult life nest-building, nest-provisioning, and hunting prey for their developing larvae (Evans and O’Neill 1981). These solitary wasps nest gregariously in vegetation-free, exposed, sandy soils at sites that are used year after year. A female sand wasp excavates a new nest each time she lays an egg. To do this, she rakes the soil with her front legs and scoops it beneath her as she digs (Evans 1966; Rau and Rau 1918). After a nest is constructed, the female wasp flattens the remaining soil mound, presumably to hide the entrance (Evans 1966). This nest excavation behavior varies among Bembix species and has been the subject of behavioral research. For example, B. Americana levels off the excavated soil mound by raking linearly while other closely related species rake in semi-circular patterns (e.g., B. pallidipicta) or do not level out the soil mound at all (e.g., B. allunga).

Bembix americana prey on several species of flies and are excellent aerial predators (Evans 2002). Like many other solitary wasps, female American sand wasps sting their prey to inject it with paralyzing venom. They fly with the paralyzed prey held tightly under their body, carrying it down into the nest and laying a single egg on it (Evans 2002). Female sand wasps dig a relatively shallow (10-27 cm deep) nest that contains 1-3 cells (Alcock 1972; Evans and O’Neill 2007). Each cell contains a single wasp larva that the female sand wasp provisions with 20-30 fresh prey items successively as the larva develops and until pupation begins. Once the larva has pupated, the adult female sand wasp closes off the cell and digs a new cell within the nest or closes the current nest entirely and digs a new nest (Alcock 1972; Evans 1970; Rau and Rau 1918). This nest provisioning behavior also varies greatly among Bembix species and has been categorized into three types: Progressive (prey is brought to larva as it develops), mass provisioning (entire food supply is brought in early in development and nest closed off), and intermediate (Frank 2022). Bembix americana displays an intermediate provisioning behavior, where they can shift between progressive and mass provisioning based on the local conditions and context.

Males emerge several days before females (known as proterandry) and remain close to the aggregate nesting site awaiting female mates. Reproductive access to females is highly competitive and groups of sand wasp males fly low over nesting sites in irregular, circular patterns waiting for emerging, unmated females (Evans 1966; Tanner and Pitts 2013). Because this conspicuous, frenetic activity occurs in the morning hours as females are beginning to emerge, it has been dubbed a “sun dance” (Evans 1966, 1970; Rau and Rau 1918). The males tend to protect territories over the nesting area and alternately fly low over the soil and land briefly on the ground. They may be attracted to female pheromones and land to locate the direction of the signal, or to sense vibrations in the soil as the females move underground (Evans 1966; Tanner and Pitts 2013). At night, males dig themselves into shallow holes, or sleeping chambers, in the soil and then re-emerge in the morning (Evans 1966).

Hosts

Food

American sand wasps prey entirely on flies to provision their developing larvae. Over 43 species of flies from the following families have been documented as prey items for this species: Anthomyiidae, Asilidae, Bombyliidae, Calliphoridae, Dolichopodidae, Muscidae, Ottidae, Sarcophagidae, Sciomyzidae, Syrphidae, Tabanidae, Tachinidae, and Therevidae (Evans and O’Neill 2007). Adults feed primarily on nectar from a variety of flowers (Spofford and Kurczewski 1992), or from extrafloral nectaries (Evans 1966).

Parasites

Several insect species are known to parasitize Bembix americana nests. Miltogrammine flies (Sarcophagidae: Miltogramminae) are ubiquitous parasites of ground-nesting wasps (Evans 1970). A common nest parasite is Senotainia trilineata, often referred to as the satellite fly (McCorquodale 1986). These flies follow female sand wasps to their nest entrance and larviposit (deposit living larvae rather than eggs) directly onto the prey item as the female wasp carries it into her nest. The progressive-provisioning behavior of Bembix americana is thought to serve as a defense against parasitism in that oftentimes the wasp larva is cared for frequently enough that parasitic fly larvae are unable to kill the host larvae, and instead both the parasitic fly and wasp larvae survive together in the nest (Evans 1970; McCorquodale 1986; Rau and Rau 1918).

Other nest parasites include bombyliid flies (Bombyliidae) and cuckoo wasps (Chrysididae). Adult wasps may also be parasitized by conopid flies (Conopidae) (Evans 1970).

Importance

Bembix americana Fabricius is a native solitary wasp and is not considered a pest. It is not known to be aggressive to humans, livestock, or pets although females may fly alarmingly close while hunting flies. Solitary ground-nesting wasps such as Bembix americana visit flowers for nectar and can be efficient pollinators of many flower species (Brock et al. 2021). American sand wasps can have a top-down regulatory effect on flies, including pest species. For example, a small nesting aggregation of 50 female American sand wasps is conservatively estimated to kill at least 5000 flies over a nesting season, so this wasp can be considered a beneficial biological control agent of nuisance flies (Brock et al. 2021; Evans 1970).

Since they prefer to nest in open areas of bare soil, they may take up residence near places of human activities, such as driveways, playgrounds, or volleyball courts. The preferred management is to avoid the area and allow these beneficial wasps to continue to their biological control of nuisance flies. Otherwise, this charismatic and gentle solitary wasp species requires no further management action.

Selected References

Alcock J. 1972. Variation in cell number in a population of Bembix americana (HYMENOPTERA: Sphecidae). Psyche, 79(3), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1155/1972/36152

Brock RE, Cini A, Sumner S. 2021. Ecosystem services provided by aculeate wasps. Biological Reviews, 96(4), 1645–1675. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12719

Evans HE. 1966. The behavior patterns of solitary wasps. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 11, 123–154. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.11.010166.001011

Evans HE. 1970. Ecological-Behavioral studies of the wasps of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 140(7), 451–511.

Evans HE. 2002. A Review of Prey Choice in Bembicine Sand Wasps (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Neotropical Entomology, 31(1), 001–011. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2002000100001

Evans HE, Matthews RW. 1968. North American Bembix, a revised key and suggested grouping. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 61(5), 1284–1299. https://academic.oup.com/aesa/article/61/5/1284/93247 https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/61.5.1284

Evans HE, O'Neill KM. 1981. Parental investment and sexual dimorphism in digger wasps (HYMENOPTERA: Sphecidae). University of Wyoming National Park Service Research Center Annual Report, 5(10), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.13001/uwnpsrc.1981.2267

Evans HE, O'Neill KM. 2007. The Sand Wasps: Natural History and Behavior. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674036611

Frank JA. 2022. The Biology and Research History of the Solitary Wasp Genus Bembix (Hymenoptera: Bembicidae): A Brief Review. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/saab050

McCorquodale DB. 1986. Digger wasp (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) provisioning flights as a defence against a nest parasite, Senotainia trilineata (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Canadian Journal of Zoology, 64, 1620–1627. https://doi.org/10.1139/z86-244

Rau P, Rau N. 1918. Wasp Studies Afield. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Spofford MG, Kurczewski FE. 1992. Counter-cleptoparasitic behaviours of species of Sphecidae (Hymenoptera) in response to Miltogrammini larviposition (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Journal of Natural History, 26(5), 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222939200770591

Tanner DA, & Pitts JP. 2013. Effects of male size on searching behaviors in the sun dance of Bembix. Western North American Naturalist, 73(2), 254–257. https://doi.org/10.3398/064.073.0218