Introduction

This publication aims to increase awareness of a commonly found fungus-feeding mite, Tarsonemus confusus, in strawberry fields. There are more than 270 species in the mite family Tarsonemidae. In Florida, Tarsonemus confusus Ewing (Acari: Tarsonemidae) sometimes appears in strawberry fields late in the season, between January and March. These mites and their eggs may be observed under the calyxes of bronzed and cracked strawberry fruits in fields with prior insect infestation. Tarsonemus confusus may be misidentified as a pest mite. In fact, without help from an expert mite taxonomist, incorrect species identification can be a major concern. Although this mite species typically does not achieve pest status on most crops, an incorrect pest identification may lead to unnecessary application of miticides, triggering a secondary pest outbreak. This publication is intended to help growers, crop consultants, crop scouts and Extension agents to distinguish Tarsonemus confusus mites from pest mites and thus reduce unnecessary, excessive, and harmful use of insecticides.

Synonymy

Tarsonemus assimillis Banks

Distribution

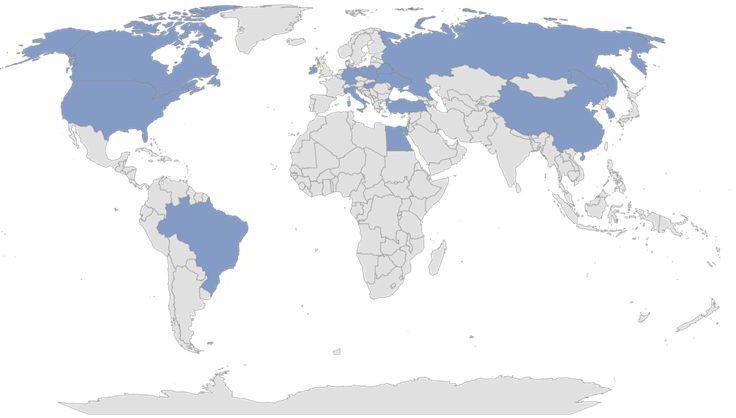

Tarsonemus confusus has extensive distribution in many parts of the world, including Belarus, Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Poland, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United States (Zhang 2003; Ripka et al. 2005; Lofego et al. 2005; Figure 1). In the southeastern United States, T. confusus has been found in low numbers in blackberry orchards in Florida and Georgia (Akyazi et al. 2021).

Credit: Zhang (2003)

Description

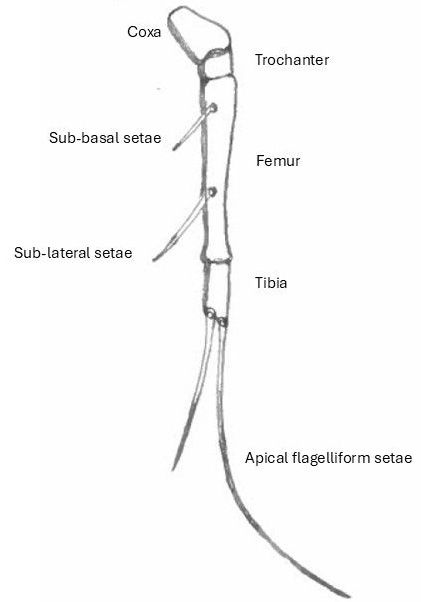

The eggs are oval to oblong and smooth surfaced. Immature stages are white and have three pairs of legs. The larvae can be differentiated from nymphs by their constricted abdomen. Adult females are larger (0.194 mm long and 0.133 mm wide) than males (0.151 mm long and 0.71 mm wide) and are brown and dark brown with four pairs of legs (Spiegelberg 1951). The fourth leg in adults is vital for identification purposes. In males, the coxa of the fourth leg is subtriangular, and the tarsal claw is short, stout, and half as long as the tibiotarsus (Spiegelberg 1951). In females, the femur in the fourth leg is longer than those in the other legs and contains two extended sub-basal and sub-lateral setae (Figure 2). The tibia is short, with very long flagelliform setae (Ewing 1939).

Credit: adapted from Ewing 1939 (Re-drawn)

Life Cycle

The life cycle of Tarsonemus confusus consists of four stages: egg, larvae, quiescent nymph, and adult (Spiegelberg 1951). Tarsonemus confusus has a haplodiploid sex-determination system in which females develop from fertilized eggs, and males develop from unfertilized eggs. The adult female lays eggs after 36 hours of emergence from the nymph stage. Eggs hatch after 54–56 hours. The young larva feeds for 24 hours and develops into a nymph. Nymphs are immobile and develop into adults within 20–32 hours. The life cycle (egg to egg) takes almost six days to complete at a temperature of 29°C (Spiegelberg 1951). Their development and reproduction are temperature dependent (Li et al. 2022). The developmental rate from eggs to adults increases with the increase in temperature from 15°C to 30°C. Temperature significantly influences oviposition, sex allocation, population growth, and survival of these mites (Li et al. 2022).

Host Range

Tarsonemus confusus is found on corn (Poaceae: Zea mays), wheat (Poaceae: Triticum aestivum), grasses (Poaceae: Poa spp.), tomato (Solanaceae: Solanum lycopersicum), apple (Rosaceae: Malus domestica) (Spiegelberg 1951), and blackberry (Rosaceae: Rubus spp.) (Akyazi et al 2021). It is also found in ornamentals such as azalea (Ericaceae: Rhododendron spp.), African violet (Gesneriaceae: Saintpaulia ionantha), cyclamen (Primulaceae: Cyclamen persicum), ivy (Araliaceae: Hedera helix), and pilea (Urticaceae: Pilea peperomioides) (Zhang 2003). Typically, this mite is found on the part of the plant where fungi are present, probably because this mite feeds on the simple sugars produced when the fungi process plant carbohydrates (Spiegelberg 1951).

Because of its fungivorous nature, this mite species is sometimes responsible for spreading fungal spores. A study found that T. confusus was accountable for spreading black dot symptoms in apples in China (Hao et al. 2010). Several pathogenic fungi, namely, Trichothecium roseum (Pers.) Link, Acremonimum stritum Gams, and several Alternaria spp. were found in the infected apple fruit. The presence of T. confusus was responsible for the occurrence of the organisms that caused black dot disease (Hao et al. 2010).

Tarsonemus confusus was also found to be associated with dry core rot disease of apples caused by Coniothyrium spp. (Michailides et al. 1994). In that study, disease incidences were higher when the mites were present along with the causal fungal agent. Michailides et al. (1994) suspected that T. confusus might have carried the fungal spores to the apple core or caused the small wound that allowed the pathogen to enter the fruit. In laboratory cultures, Tarsonemus confusus was found to feed on a diverse group of fungi, including Trichoderma, Geomyces, Cladosporium, Hormiactis, Stachybotris, Botrosporium, Cladobotryium, Beauveria, and Unoclodium (Lindquist 1986). When offered both, T. confusus preferred Alternaria spp. as a food source over Cladosporium spp. from apple foliage. When separate groups of mites were offered only one of the two species of fungi, Cladosporium was fed upon as frequently as or more frequently than Alternaria (Beleczewski and Harmsen 1994). Again, it is important to stress that most records of T. confusus occurring on these plants are not associated with direct feeding upon the plant tissues but rather upon byproducts produced by the fungus developing on these plants. For example, Li et al. (2022) used Fusarium spp. as a food source of T. confusus to study the effect of the temperature on the developmental time of the mites.

Differences between Tarsonemus confusus and Phytonemus pallidus

Tarsonemus confusus is often misidentified as the cyclamen mite Phytonemus pallidus (Banks) (Acari: Tasonemidae; Figures 3–5) in strawberries (Zalom et al. 2008). However, there are detectable differences between the morphological characters of the two species that allow them to be distinguished with careful observation (Table 1). Tarsonemus confusus has never been reported to be the causative agent of any damage to strawberries stemming from the mite’s direct feeding on plant tissue or sap. Proper identification is essential before applying acaricides in the field because unnecessary pesticide application can harm beneficial insects and other non-target organisms.

Credit: Sriyanka Lahiri, UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: Justin Renkema, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Credit: Justin Renkema, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Table 1. Morphological differences between Phytonemus pallidus and Tarsonemus confusus.

Economic Importance

Tarsonemus confusus is not presently considered a pest of strawberry in Florida. These mites have been found under the calyx of bronzed and cracked fruits (Figure 6).

Credit: Sriyanka Lahiri, UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: Sriyanka Lahiri, UF/IFAS GCREC

Management

As mentioned earlier, T. confusus is often misidentified as P. pallidus. However, the presence of P. pallidus in the field can be confirmed by the damage symptoms on the infected plants (Figure 7). The correct identification of specimens must be done to rule out the presence of economically important pests. There is no report of T. confusus feeding directly on the strawberry plant tissue. No management is currently needed for T. confusus because they are not reported as an economic pest of strawberry.

Selected References

Akyazi, R., C. Welbourn, and O. E. Liburd. 2021. “Mite species (Acari) on blackberry cultivars in organic and conventional farms in Florida and Georgia, U.S.A.” Acarologia 61:31–45. https://doi.org/10.24349/acarologia/20214414

Beleczewski, R . F. and R. Harmsen. 1994. In vitro feeding preferences of the fungivorous mite Tarsonemus confusus Ewing (Tarsonemidae). In R. B. Halliday, D. E. Walter, H. C. Proctor, R. A. Norton & M. J. Colloff (eds.). Proceedings 10th International Congress. Australia, Canberra, Collingswood, Victoria, CSIRO Publishing, pp. 61–65.

Ewing, H. E. 1939. “A revision of the mites of the subfamily Tarsoneminae of North America, the West Indies, and the Hawaiian Islands.” Technical Bulletin, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC (653).

Hao, B., L. Yu, C. Xu, L. He, and R. Jiao. 2010. “Tarsonemus confusus causes black-dot disease of bagged fruits on apple trees and its control.” Journal of Fruit Science 27:956–960.

Li, L., L. Yu, L. He, X. Z. He, R. Jiao, and C. Xu. 2022. “Temperature-dependent development and reproduction of Tarsonemus confusus (Acari: Tarsonemidae): an important pest mite of horticulture.” Experimental and Applied Acarology 88:301–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-022-00761-4

Lindquist, E. E. 1986. “The world genera of Tarsonemidae (Acari: Heterostigmata): a morphological, phylogenetic, and systematic revision, with a reclassification of family-group taxa in the Heterostigmata.” The Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 118:1–517. https://doi.org/10.4039/entm118136fv

Lofego, A. C., R. Ochoa, and G. D. Moraes. 2005. “Some tarsonemid mites (Acari: Tarsonemidae) from the Brazilian ‘Cerrado’ vegetation, with descriptions of three new species.” Zootaxa, 823:1–27. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.823.1.1

Michailides, T. J., D. P. Morgan, E. Mitchum, and C. H. Crisosto. 1994. “Occurrence of moldy core and core rot of fungi apple in California.” Central Valley Postharvest Newsletter. Cooperative Extension, University of California, Kearney Agricultural Centre, Parlier, CA. 3:6–9.

Ripka, G., A. Fain, A. Kazmierski, S. Kreiter, and W. L. Magowski. 2005. “New data to the knowledge of the mite fauna of Hungary (Acari: Mesostigmata, Prostigmata and Astigmata).” Acta Phytopathologica et Entomologica Hungarica 40:159–176. https://doi.org/10.1556/APhyt.40.2005.1-2.13

Spiegelberg, W. E. 1951. “Some observations on the life history of the mite, Tarsonemus confusus Ewing.” Masters’ thesis, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio.

Zalom, F. G., P. B. Thompson, and N. Nicola. 2008. “Cyclamen mite, Phytonemus pallidus (Banks), and other tarsonemid mites in strawberries.” In VI International Strawberry Symposium 842:243–246. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.842.39

Zhang, Z. Q. 2003. “Mites of greenhouses: Identification, biology and control”. Cambridge, UK, CABI Publishing, 244 pp.