Introduction

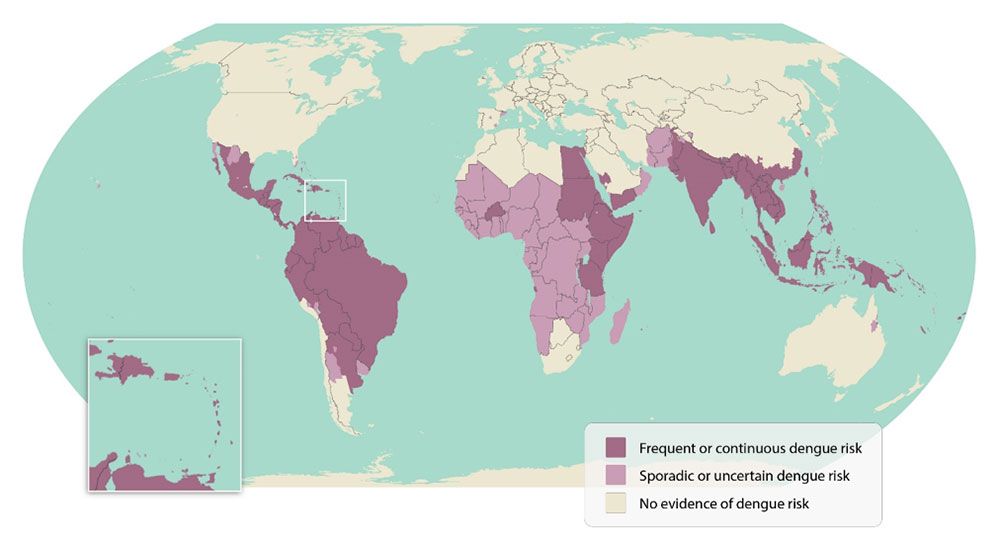

The purpose of this publication is to introduce dengue (sometimes called dengue fever) the disease and its causative agent, dengue virus, to stakeholders, including the general public, mosquito control professionals, medical practitioners, and public health decision makers. Dengue is a viral disease that spreads from person to person via mosquito bites. Most people who contract dengue experience no symptoms or only mild, flu-like symptoms. In rare cases, severe dengue may result in hospitalization or even prove fatal if left untreated. Dengue is a major global health concern with around 390 million infections annually, a quarter of which show clinical signs (Bhatt et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2021). Endemic in over 100 countries (Figure 1; Yang et al. 2021), dengue imposes an estimated US$9 billion per year due to medical expenses and loss of productivity (Shepard et al. 2016).

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areas-with-risk/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/around-the-world.html

Over the past several decades, dengue has become a major global concern. Its spread is exacerbated by urbanization, economic inequality, and climate change, all of which foster mosquito breeding (Murray et al. 2013). Additionally, globalization accelerates the rapid movement of both people and goods such as used tires, a favored mosquito larval habitat, allowing both the mosquitoes and the virus to spread. Together, these factors drive increased transmission of dengue. With no specific treatment for dengue and limited availability of vaccines, controlling Aedes mosquito populations is crucial to help reduce dengue risk (Deng et al. 2020; Silva and Fernandez-Sesma 2023).

Mosquito Vectors of Dengue

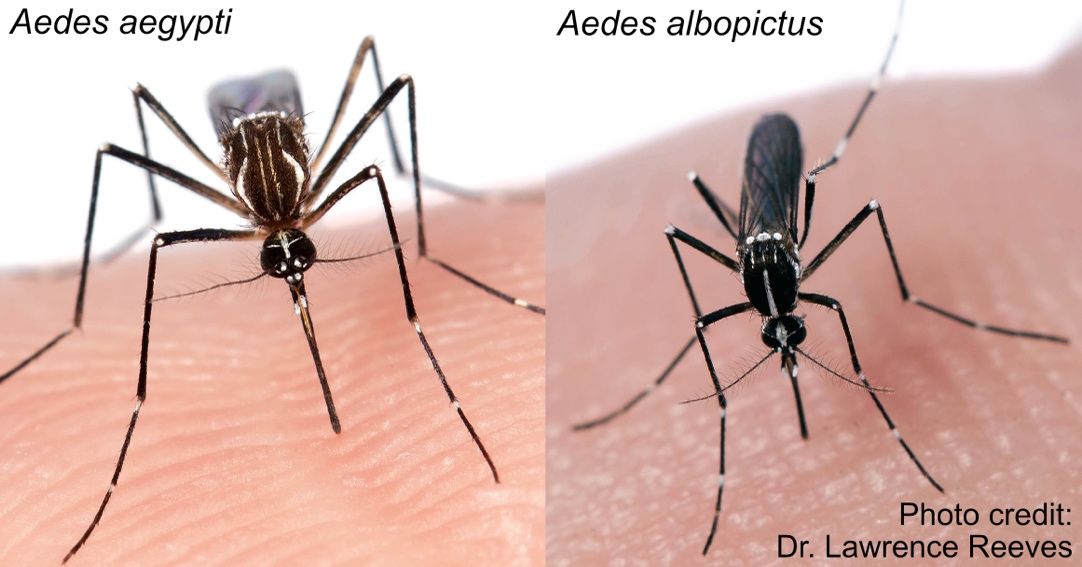

A disease vector is an organism (such as an insect) that transmits infectious diseases to other living organisms (such as humans). There are two main mosquito vectors responsible for spreading dengue: the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, and the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus (Figure 2). They also transmit Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever viruses. These mosquitoes lay their eggs in both natural and artificial water containers. Buckets, flowerpots, and discarded tires, as well as natural reservoirs like tree holes and coconut shells can all support larval mosquitoes. Mosquitoes undergo a four-stage life cycle. They hatch from eggs into larvae, which live in water, and go through several molts before turning into pupae, a non-feeding aquatic stage. Then, they emerge as flying adults, ready to mate. Female mosquitoes seek blood meals necessary for egg production. The preference of both species for human blood and their close association with human habitats facilitate their reproduction and the spread of viruses.

Credit: L. Reeves, UF/IFAS FMEL

Dengue Transmission Cycle

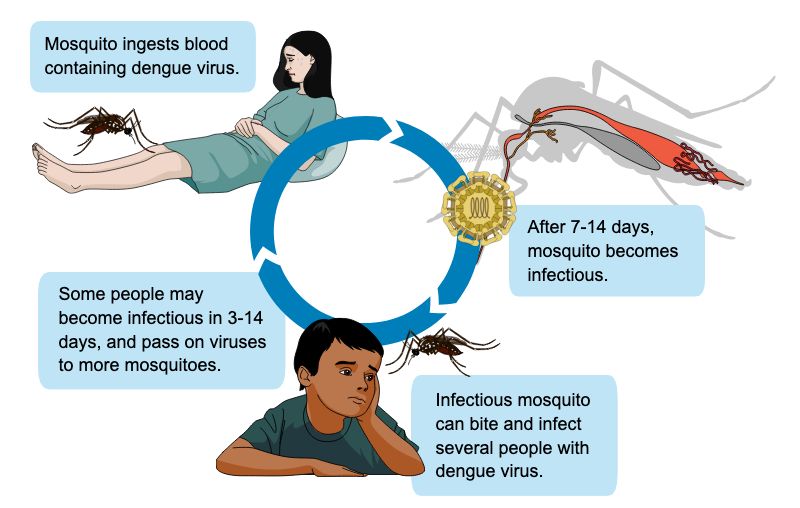

The dengue transmission cycle (Figure 3) begins when a female mosquito bites a person who is infected with dengue virus and ingests the virus. The virus then progresses through the mosquito’s internal tissues, reaching the insect’s salivary glands within 7–14 days. At this point, the infectious mosquito can infect new people when it bites them (Guzman et al. 2016). After a person receives an infectious bite, symptoms may develop in 4–7 days (Guzman et al. 2016) as the virus infects and multiplies within immune cells, spreading through the lymphatic system (Bhatt et al. 2021). Infected individuals can then pass the virus to new Aedes mosquito vectors, perpetuating the cycle.

Credit: P. Thongsripong, UF/IFAS FMEL

Dengue Virus

Dengue virus belongs to a family of viruses called Flaviviridae. There are four different types of dengue virus, known as dengue serotypes 1 through 4, which are closely related to each other. These four dengue serotypes shape our immune response to infection. When a person is infected with one dengue serotype, that person develops lifelong immunity against that specific serotype but only temporary and partial immunity to the other three (Hussain et al. 2023). Antibodies produced after the first dengue infection can promote infection with the other serotypes, potentially leading to more serious illness, known as severe dengue (Bhatt et al. 2021). The unique interplay between the serotypes and the human immune system has made it difficult to develop an effective vaccine that simultaneously protects against all four dengue virus serotypes.

Signs and Symptoms of Dengue Infection

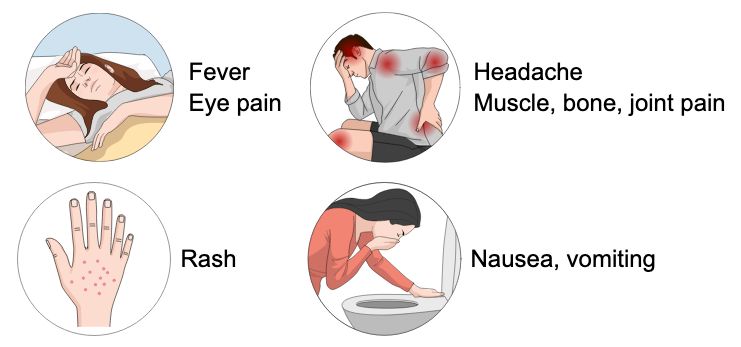

Most dengue infections are asymptomatic, but when symptoms occur, they are typically mild and include fever, headaches, body aches, eye pain, nausea, vomiting, and a rash (Figure 4; Wilder-Smith et al. 2019). Dengue can often be mistaken for other flu-like diseases. Recovery usually happens within 2–7 days. Severe dengue, although rare, can occur in patients who previously had dengue, young children, pregnant women, and those with chronic health conditions. Severe dengue manifests after the initial fever phase as abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, bleeding of the gums or nose, blood in stool or vomit, weakness of the body, rapid heartbeat, difficulty breathing, and dehydration (Wilder-Smith et al. 2019). Severe dengue requires immediate medical care.

Credit: P. Thongsripong, UF/IFAS FMEL

Dengue in Florida

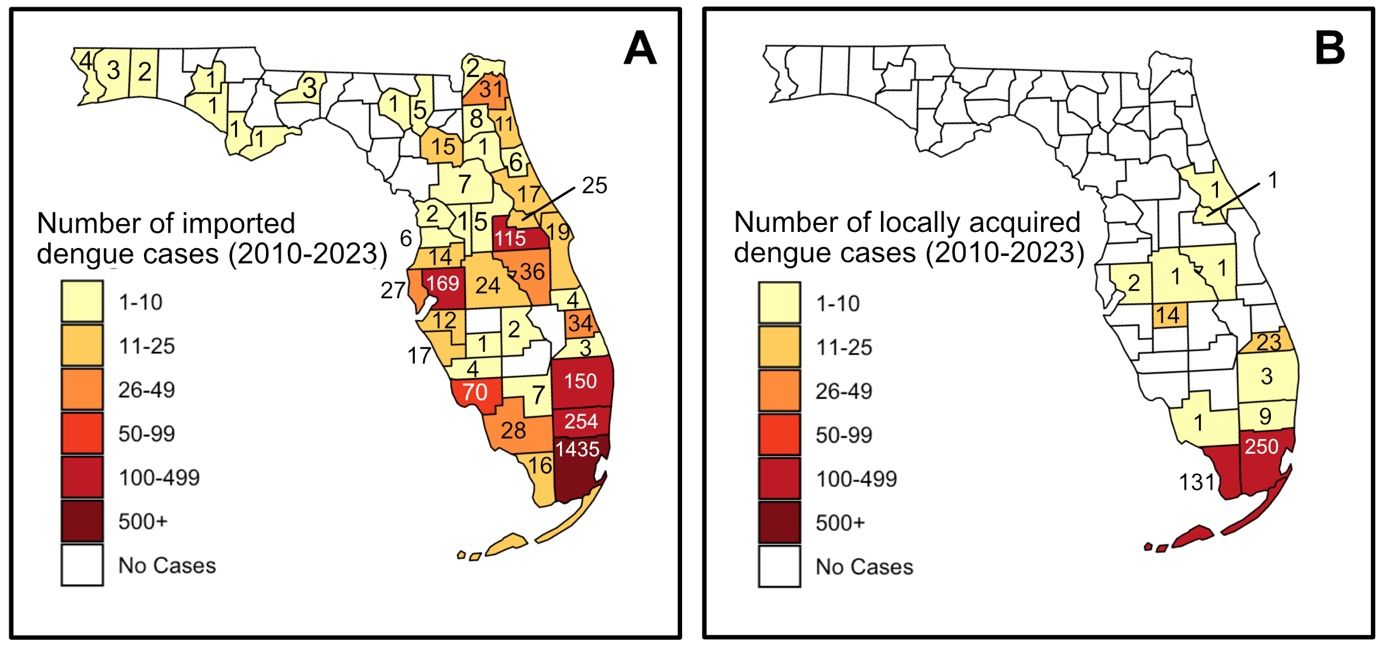

While dengue is not common in the continental United States, it is endemic in some US territories such as Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and American Samoa (Ryff et al. 2023). In the continental United States, most dengue cases are associated with travel, although sporadic cases resulting from transmission by local mosquitoes does occur in Florida, Texas, and other southern states (Rivera et al. 2020). Between 2010 and 2023 there were 2600 travel-associated dengue cases in Florida (Figure 5 and Table 1; the Florida Department of Health’s Mosquito-Borne Disease Surveillance page at https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/surveillance.html). Most of these cases were detected in Miami-Dade County, but other hotspots include Broward, Hillsborough, Palm Beach, and Orange Counties. There was a total of 437 cases of local dengue transmission in Florida between 2010 and 2023. These local cases occur when a person is bitten and infected by an infectious mosquito while the person is in Florida. Local transmission of dengue occurred across 12 different counties. Most cases occurred in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties, where conditions are favorable for the primary dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Notably, 217 of these cases occurred in Miami-Dade County between 2022 and 2023.

Credit: The figure was created using R (version 4.4.0, released 2024-04-24; R Core Team 2024) and RStudio (version 2024.04.1+748; Posit Team 2024), utilizing the usmap (Di Lorenzo 2024) and sf (Pebesma 2018; Pebesma & Bivand 2023) packages.

Table 1. Number of dengue cases (imported and locally acquired) in Florida counties from 2010–2023.

Since 2010, Florida recorded more than 200 dengue cases in 2019, 2022, and 2023 (Figure 6; Table 3). More than 50 local cases were recorded during 2010, 2020, 2022, and 2023. The local transmission season in Florida occurs between June and November, with a peak occurring between August and October. Low numbers of dengue cases have been observed in most other months. The vast majority of imported dengue cases detected in Florida have resulted from travel to the Caribbean, particularly Cuba and Puerto Rico, where dengue is endemic (Table 2). All four dengue serotypes have been detected in Florida since 2012, but which of the four is the most prominent dengue serotype fluctuates regularly. This is normal for dengue virus; it is common for multiple viral serotypes and genotypes to circulate simultaneously and for the circulating viruses to change over time (Alagarasu et al. 2021). Since 2012, dengue virus 3 has been the most commonly detected dengue serotype in Florida, accounting for about half of all cases. However, before 2022, both dengue 1 and dengue 2 were more common in Florida.

Credit: E. P. Caragata, UF/IFAS FMEL

Table 2. Number of imported dengue cases in Florida by region of origin (2010–2023).

Table 3. Yearly breakdown of percentage of dengue cases in Florida by dengue serotype (2012–2023).

Diagnosis and Treatment

Clinicians should test for dengue in patients showing clinical symptoms compatible with dengue illness and who have recently returned from regions where dengue is endemic. The choice of diagnostic assay depends on the timing of sample collection. Early on (e.g., less than 5 days after the onset of fever), dengue can be diagnosed via direct detection of the virus or its components such as viral RNA or NS1 antigens. Later, diagnosis typically involves a combination of tests to detect the NS5 antigen and IgM antibody (Guzman and Harris 2015). Cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses occurs when the patient has been exposed to other flaviviruses or vaccinated against flaviviruses such as yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis. Cross-reactivity can complicate results (Wilder-Smith et al. 2019). In such cases, further molecular and serological diagnostic testing for dengue and other flaviviruses may be warranted.

There are currently no antiviral drugs specific for dengue. Patients experiencing mild dengue are advised to remain well hydrated, to stay at home, and to avoid mosquito bites. Patients with fever and pain should avoid aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, because of their anticoagulant properties (CDC 2024). Severe dengue cases require close monitoring and medical assistance. Although there is no treatment for severe dengue, early detection and prompt medical care can lead to improve outcomes.

Prevention and Control

Effective prevention and control of dengue virus requires a multi-faceted approach involving both community participation and coordinated top-down public health strategies (Erlanger et al. 2008). One of the primary dengue controlling methods is to remove containers that could fill with water, thus eliminating standing water, where Aedes mosquitoes breed. When water cannot be removed, larvicides or biological control can be applied to kill larvae (Achee et al. 2015). Mosquito bites can be prevented through the use of insect repellents that contain EPA-registered active ingredients (e.g., DEET, picaridin, and oil of Lemon Eucalyptus), long-sleeved clothing, mosquito nets and screens, and by remaining indoors during peak mosquito times.

Most Florida counties have mosquito control programs that implement Integrated Pest Management utilizing holistic approaches to suppress mosquito populations (Moise et al. 2020; Kondapaneni et al. 2021). These programs may apply targeted strategies like source reduction and aerial pesticide spraying to control mosquito populations during high-risk periods as warranted by surveillance data. These measures should be carefully managed to avoid environmental impacts and the development of pesticide resistance in mosquitoes. Ongoing research and development of dengue control methods offer hope for long-term prevention. Although their eligibility criteria are limited, the recent availability of the Dengvaxia CYD-TDV and Qdenga TAK-003 vaccines represent a critical step in the fight against dengue (Tully and Griffiths 2021). Biological control methods, such as the use of genetically modified mosquitoes or Wolbachia bacteria, are being explored as sustainable control method (Flores and O’Neill 2018; Utarini et al. 2021).

References

Achee, N. L., F. Gould, T. A. Perkins, R. C. Reiner Jr, A. C. Morrison, S. A. Ritchie, D. J. Gubler, R. Teyssou, and T. W. Scott. 2015. “A Critical Assessment of Vector Control for Dengue Prevention.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 9 (5): e0003655. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003655

Alagarasu, K., J. A. Patil, M. B. Kakade, A. M. More, B. Yogesh, P. Newase, S. M. Jadhav, et al. 2021. “Serotype and Genotype Diversity of Dengue Viruses Circulating in India: A Multi-Centre Retrospective Study Involving the Virus Research Diagnostic Laboratory Network in 2018.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 111:242–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.045

Bhatt, P., P. S. Sabeena, M. Varma, and A. Govindakarnavar. 2021. “Current Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Dengue Virus Infection.” Current Microbiology 78 (1): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02284-w

Bhatt, S., P. W. Gething, O. J. Brady, J. P. Messina, A. W. Farlow, C. L. Moyes, J. M. Drake, et al. 2013. “The Global Distribution and Burden of Dengue.” Nature 496 (7446): 504–507. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12060

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD). 2024. "Areas with Risk of Dengue." https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areas-with-risk/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/around-the-world.html.

Deng, S. Q., X. Yang, Y. Wei, J. T. Chen, X. J. Wang, and H. J. Peng. 2020. “A Review on Dengue Vaccine Development.” Vaccines 8 (1): 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8010063

Di Lorenzo, P. 2024. _usmap: US Maps Including Alaska and Hawaii_. R package version 0.7.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=usmap

Erlanger, T. E., J. Keiser, and J. Utzinger. 2008. “Effect of Dengue Vector Control Interventions on Entomological Parameters in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” Medical and Veterinary Entomology 22 (3): 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00740.x

Flores, H. A., and S. L. O’Neill. 2018. “Controlling Vector-Borne Diseases by Releasing Modified Mosquitoes.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 16 (8): 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0025-0

Guzman, M. G., D. J. Gubler, A. Izquierdo, E. Martinez, and S. B. Halstead. 2016. “Dengue Infection.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.55

Guzman, M. G., and E. Harris. 2015. “Dengue.” The Lancet 385 (9966): 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60572-9

Hussain, Z., S. Rani, F. Ma, W. Li, W. Shen, T. Gao, J. Wang, and R. Pei. 2023. “Dengue Determinants: Necessities and Challenges for Universal Dengue Vaccine Development.” Review in Medical Virolology 33 (2): e2425. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2425

Kondapaneni, R., A. N. Malcolm, B. M. Vazquez, E. Zeng, T. Y. Chen, K. J. Kosinski, A. L. Romero-Weaver, et al. 2021. “Mosquito Control Priorities in Florida—Survey Results from Florida Mosquito Control Districts.” Pathogens 10 (8): 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10080947

Moise, I. K., R. D. Xue, L. C. Zulu, and J. C. Beier. 2020. “A Survey of Program Capacity and Skills of Florida Mosquito Control Districts to Conduct Arbovirus Surveillance and Control.” Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 36 (2): 99–106. https://doi.org/10.2987/20-6924.1

Murray, N. E. A., M. B. Quam, and A. Wilder-Smith. 2013. “Epidemiology of Dengue: Past, Present and Future Prospects.” Clinical Epidemiology 5:299–309. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S34440

Patel, S. S., P. Winkle, A. Faccin, F. Nordio, I. LeFevre, and C. G. Tsoukas. 2023. "An Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial of TAK-003, a Live Attenuated Dengue Tetravalent Vaccine, in Healthy US Adults: Immunogenicity and Safety when Administered during the Second Half of a 24-Month Shelf-Life.” Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 19 (2): 2254964. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2254964

Pebesma, E., 2018. "Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data." The R Journal 10 (1): 439–446. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-009

Pebesma, E., and R. Bivand. 2023. Spatial Data Science: With Applications in R. Chapman and Hall/CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429459016

Posit team. 2024. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA. URL https://www.posit.co/.

R Core Team. 2024. "R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing." R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Rivera, A., L. E. Adams, T. M. Sharp, J. A. Lehman, S. H. Waterman, and G. Paz-Bailey. 2020. “Travel-Associated and Locally Acquired Dengue Cases — United States, 2010–2017.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries 69 (6): 149–154. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6906a1

Ryff, K. R., A. Rivera, D. M. Rodriguez, G. A. Santiago, F. A. Medina, E. M. Ellis, J. Torres, A. Pobutsky, J. Munoz-Jordan, G. Paz-Bailey, L. E. Adams. 2023. “Epidemiologic Trends of Dengue in U.S. Territories, 2010–2020.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries 72 (4): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7204a1

Shepard, D. S., E. A. Undurraga, Y. A. Halasa, and J. D. Stanaway. 2016. “The Global Economic Burden of Dengue: A Systematic Analysis.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 16 (8): 935–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00146-8.

Silva, J. P., and A. Fernandez-Sesma. 2023. “Challenges on the Development of a Dengue Vaccine: A Comprehensive Review of the State of the Art.” Journal of General Virology 104 (3): 001831. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001831

Tully, D., and C. L. Griffiths. 2021. “Dengvaxia: The World’s First Vaccine for Prevention of Secondary Dengue.” Therapeutic Advances in Vaccines and Immunotherapy 9:25151355211015839. https://doi.org/10.1177/25151355211015839

Utarini, A., C. Indriani, R. A. Ahmad, W. Tantowijoyo, E. Arguni, M. R. Ansari, E. Supriyati, D. S. Wardana, Y. Meitika, and I. Ernesia. 2021. “Efficacy of Wolbachia-Infected Mosquito Deployments for the Control of Dengue.” New England Journal of Medicine 384 (23): 2177–2186. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2030243

Wilder-Smith, A., E. Ooi, O. Horstick, and B. Wills. 2019. “Dengue.” The Lancet 393 (10169): 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32560-1

Yang, X., M. B. M. Quam, T. Zhang, and S. Sang. 2021. “Global Burden for Dengue and the Evolving Pattern in the Past 30 Years.” Journal of Travel Medicine 28 (8): taab146. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taab146