Introduction

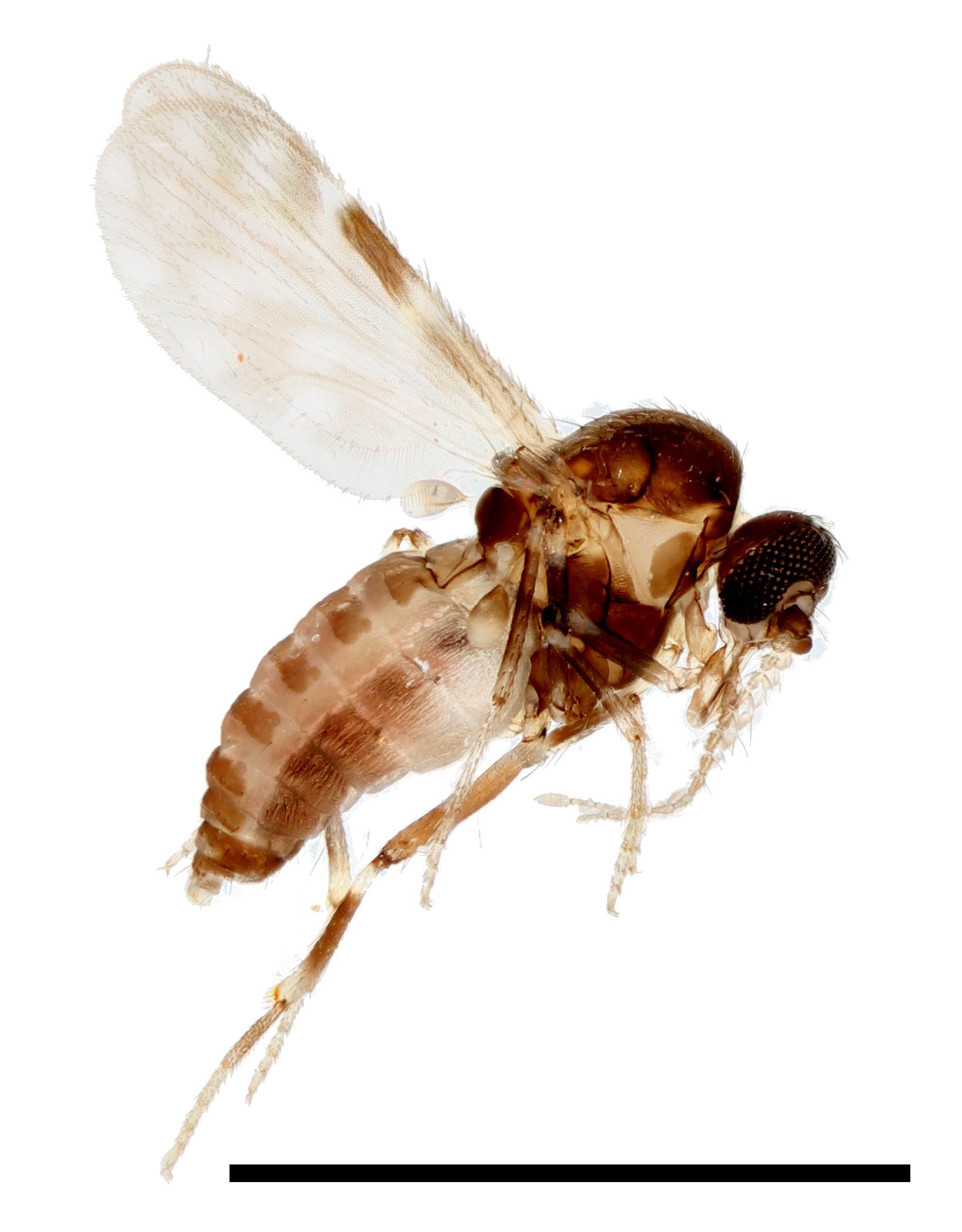

Culicoides paraensis Goeldi (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) (Figure 1) is a species of biting midge, also sometimes called sand flies and no-see-ums. This species is found throughout forested areas of North and South America. “Paraensis” in the species name means “from Pará,” Pará being a state in the Amazon Region of Brazil. In cacao- and banana-producing areas of that region (Pará and Amazonas States of Brazil), Culicoides paraensis can reach very high densities, because the larvae of this biting midge can develop in banana tree stumps and in discarded husks of cacao fruits (LeDuc and Pinheiro 2019). In the United States, Culicoides paraensis breeds almost exclusively in wet tree holes (Blanton and Wirth 1979). In the Amazon Region of South America, Culicoides paraensis is the only confirmed vector of a potentially deadly human pathogen, Oropouche virus (OROV), which is spreading beyond its endemic range of the Amazon Basin. This article provides an in-depth profile of Culicoides paraensis, a species that is relevant to Florida due to its propensity to bite humans and its potential to transmit a human pathogen. This profile is intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Distribution

The distribution of Culicoides paraensis is principally driven by the distribution and abundance of its natural larval habitat, wet treeholes in hardwood trees. This biting midge species has been recorded from a very large portion of the Western Hemisphere, from the northeastern United States through Central America and the Caribbean, and the northern two-thirds of South America. Culicoides paraensis was first described from specimens collected in the state of Pará, Brazil, near the city of Belem (Figure 2). In Central America it is recorded from Mexico and Panama but probably occurs throughout the region (Wirth and Felippe-Bauer 1985). In South America Culicoides paraensis occurs from Colombia to Brazil in the North, south through Bolivia and northern Argentina (Ayala et al. 2022). In the United States, Culicoides paraensis has been recorded from a number of eastern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas) (Blanton and Wirth 1979; Borkent and Spinelli 2000) but is also sporadically reported from farther west (Colorado, Nebraska, and Oklahoma). In Florida, Culicoides paraensis is most common in the northern half of the state and rarely encountered south of Lake Okeechobee (Blanton and Wirth 1979). It is most common in areas with extensive hardwood forests.

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Description

Immature Stages

In general, eggs of Culicoides are long, narrow, and slightly curved or crescent shaped. They are extremely small, generally not longer than a quarter of a millimeter (less than one one-hundredth of an inch). Culicoides eggs are pale when first laid, but quickly darken, turning brown or black within a few hours. The egg of Culicoides paraensis has not been formally described, but it likely resembles that of other biting midges.

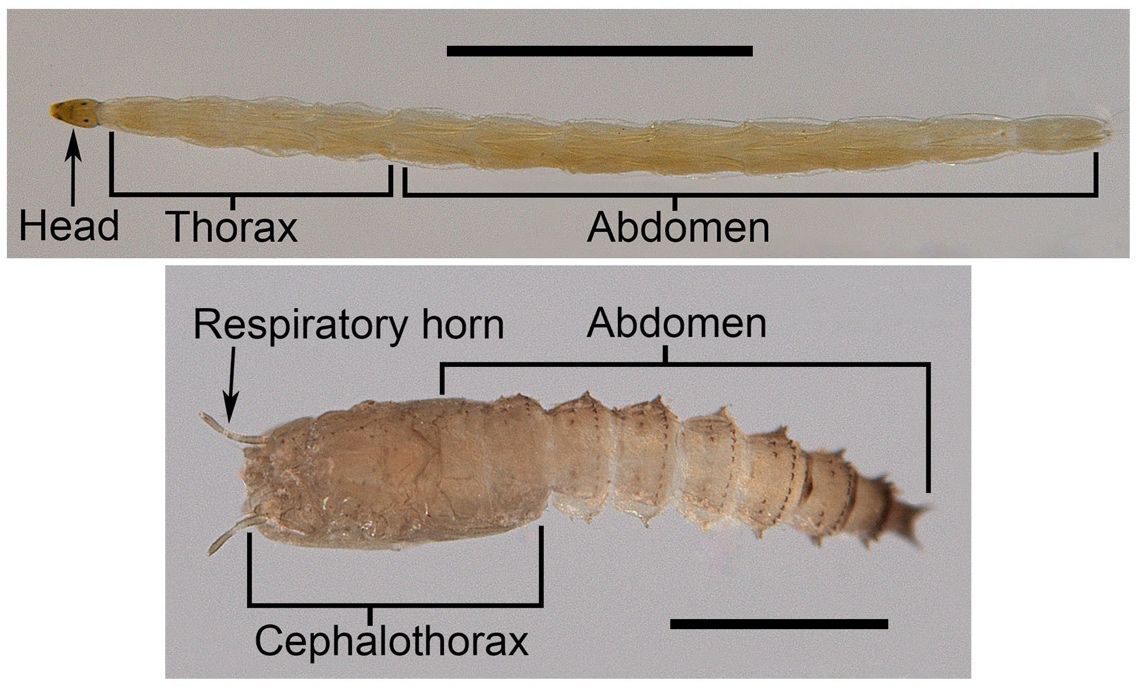

The larva of Culicoides paraensis is long and thin (~2.5 mm [~0.1 in] long, Ayala et al. 2022; Figure 3) and lacks appendages. The head is very small and darker than the thorax and abdomen, both of which are pale yellowish and segmented (Ayala et al. 2022). The antennae and eyes of the larva are tiny. The larva of Culicoides paraensis is very similar to that of Culicoides debilipalpis, a closely related species that also develops in treeholes. The two species can be told apart by the broader head capsule and stouter mandible of Culicoides debilipalpis (Ayala et al. 2022).

The pupa of Culicoides paraensis is typically darker than the larva, much stouter (1.5 mm [0.06 in] long), and has an overall spiny appearance (Ayala et al. 2022, Figure 3). The head and thorax are fused into a “cephalothorax” that bears the noticeable respiratory appendages (sometimes called “horns”) the pupa uses for breathing. The abdomen is divided into nine visible segments with lateral spines, that contribute greatly to the spiny appearance of the pupa. Segments one and two of the abdomen appear fused to the cephalothorax, while segments three through nine are separated and articulate freely. The pupae of Culicoides paraensis and Culicoides debilipalpis can be told apart by differences in the dorsal apotome, the respiratory horns, and some microscopic sensory structures of the head.

Despite the medical importance of Culicoides paraensis, the larval and pupal stages of this species were not described until the 1990s (Murphree and Mullen 1991; Lamberson et al. 1992). Ayala et al. (2022) redescribed the larva and pupa of Culicoides paraensis based upon specimens from northern Argentina.

Credit: Ayala et al. (2022) ©Magnolia Press, reproduced with permission from the copyright holder.

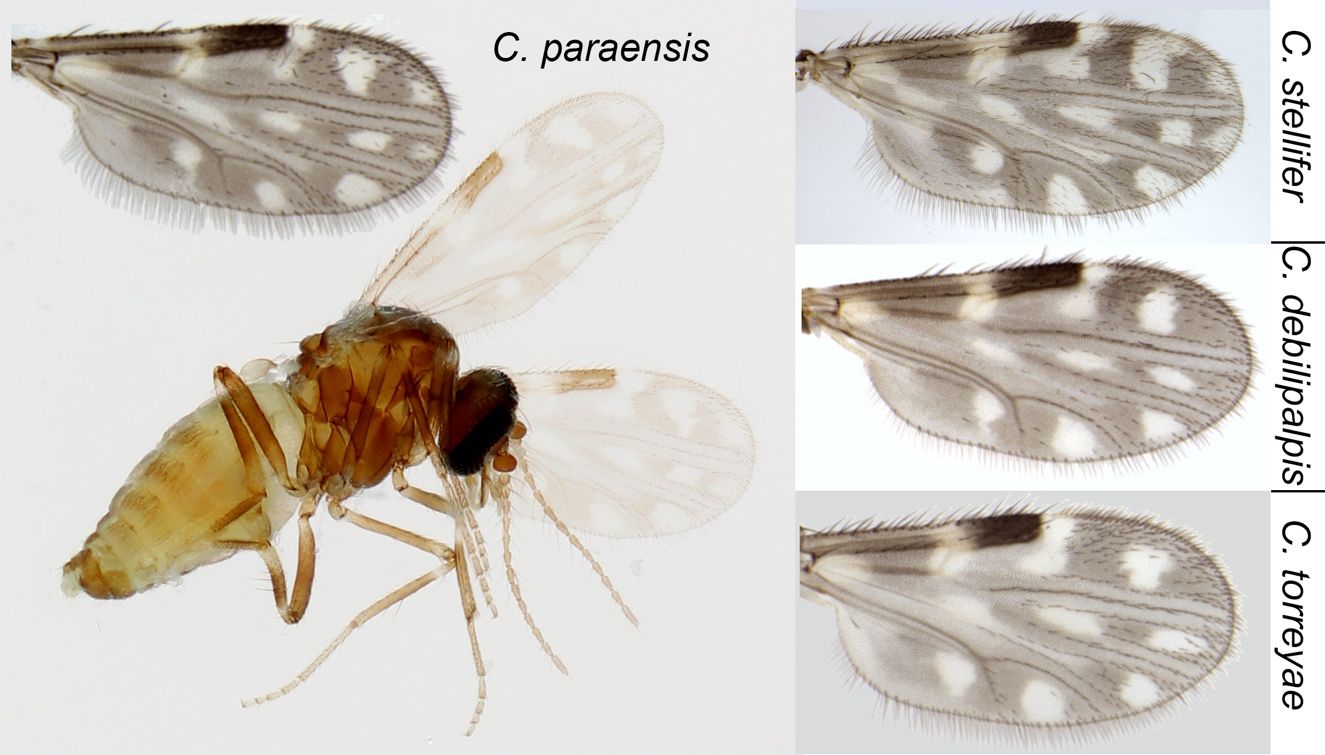

Adult

Culicoides paraensis is similar to other species of the “paraensis group” of the subgenus Haematomyidium. The adults are quite small, with a total length of about 1 mm (roughly one 25th of an inch). The thorax and abdomen are dark brown, and the legs are mostly dark with pale bands on some segments. The wings have numerous pale spots that are arranged in rows (Figure 4). In the eastern United States, adults of Culicoides paraensis are most likely to be confused with Culicoides debilipalpis, Culicoides torreyae, or Culicoides stellifer (Figure 4). These three species are generally similar in appearance but can be differentiated by slight differences in the presence and shape of pale spots in the outer wing margin and the size of dark and pale markings on the legs (Blosser et al. 2024).

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Eggs, Larvae, and Pupae

Very little is known about the eggs, larvae, and pupae of Culicoides paraensis in nature. The larvae and pupae were only described in the early 1990s, so most of the information that is known about the immature stages of this biting midge is extrapolated from records of adults that emerged from samples of larvae and/or pupae that were not identifiable at the time of collection. Blanton and Wirth (1979) summarize records of immatures collected from various parts of the species’ wider distribution. In North America, larvae of Culicoides paraensis have only been collected from wet treeholes (Figure 5) or sap flow of hardwood trees. In the tropical portions of this species’ range (Trinidad and Brazil, for example), larvae of Culicoides paraensis are frequently found in rotting husks of cacao or calabash, in addition to wet treeholes. Piles of discarded cacao husks can produce very large numbers of Culicoides paraensis adults (LeDuc and Pinheiro 1989). It is important to note that Culicoides paraensis is not known to breed in water-filled manmade containers (Hribar 2008) or bromeliads.

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS

Adults

Culicoides paraensis is not effectively captured by light traps, which are probably the most common method of studying biting midge activity. Therefore, much of the information about the seasonal and daily patterns of Culicoides paraensis activity is based upon records of females biting researchers or their subjects in nature. In the eastern United States, adults of Culicoides paraensis are mainly active in spring, summer, and fall, and mainly bite during the daytime, particularly late afternoon (Blanton and Wirth 1979). They do not commonly bite during the night, which may explain why they are rarely captured by light traps.

Detailed field studies of the biting habits of Culicoides in bottomland habitats of Tennessee and South Carolina (Snow 1955; Snow et al. 1958) placed human insect collectors on platforms at various heights in the forest and captured the biting insects (mosquitoes, midges, and others) that attempted to bite them. Culicoides paraensis was often found to be the most common species biting the researchers during the day, and females actively attacked their hosts on platforms in the treetops. Blood meal analysis, a technique that identifies the host animal(s) of blood-feeding organisms through host DNA (or other specific marker), has revealed that, in addition to humans, Culicoides paraensis mainly bites small or medium-sized mammals, such as squirrels and raccoons (McGregor et al. 2019), They have also been recorded biting rabbits and chickens in Virginia (Humphreys and Turner 1973).

Medical and Veterinary Importance

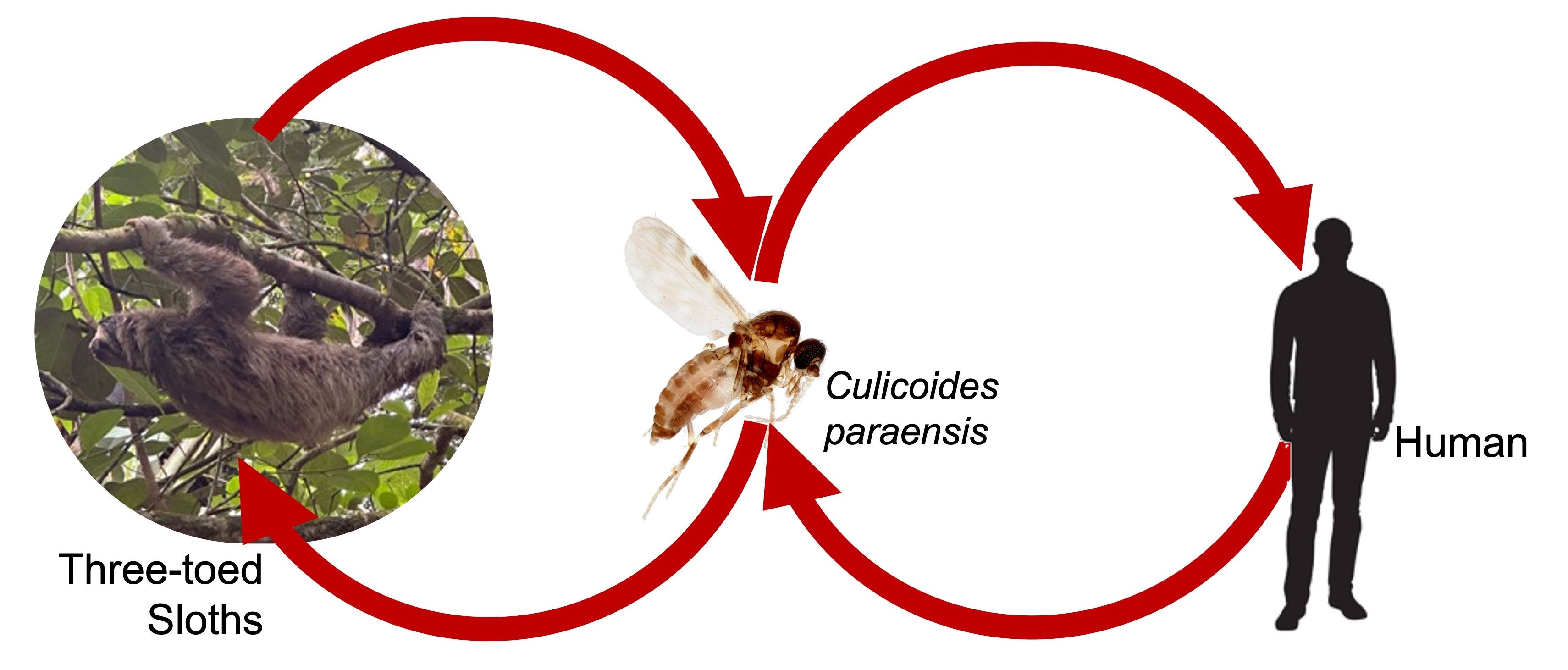

Culicoides paraensis is the only confirmed vector of Oropouche virus (OROV), an Orthobunyavirus that causes significant disease in humans in the American Tropics. Recent studies show that this virus is expanding beyond its native range to other regions, including Haiti and Cuba (Benitez et al. 2024). Field studies in Brazil found that Culicoides paraensis was one of two insects found naturally infected with OROV (Pinheiro et al. 1981), the other being the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Laboratory studies confirmed that Culicoides paraensis was capable of transmitting OROV from infected humans to susceptible hamsters (Pinheiro et al. 1982). The natural hosts of OROV are sloths (Pinheiro et al. 1981), which serve as a source of the virus for vectors (Figure 6).

Credit: Nathan Burkett-Cadena, UF/IFAS. Three-toed sloth photo by Daniel Burkett-Cadena, used with permission.

Surveillance and Management

Because of the particular larval habitat of Culicoides paraensis (wet treeholes), source reduction to reduce density of this no-see-ums species is probably not feasible. Chemical control of adults with ultra-low-volume insecticides may be effective, but timing of adulticides may need to be shifted from dusk (the typical period of application) to late afternoon (the period of peak biting), which can lower the efficacy of the chemical due to sunlight and high temperature. No information is available on insecticide susceptibility of Culicoides paraensis. However, a number of other Culicoides species in the eastern United States are susceptible to a wide range of adulticides commonly used to control mosquitoes (Linley et al. 1988; Linley and Jordan 1992).

The effectiveness of repellents for protecting against midges is a matter of debate. DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) is probably the most widely used mosquito repellent in the United States. Several studies indicate that DEET can reduce the numbers of midge bites (reviewed in Harrup et al. 2016). However, the reduction may not be adequate, depending on individual thresholds for bites. A number of repellents that contain essential oils of aromatic plants (e.g., rosemary, lavender, vanilla) are marketed as biting midge repellents. However, the efficacy of such products has not been rigorously tested (Harrup et al. 2016).

Selected References

Ayala, M. M., M. F. Diaz, G. R. Spinelli, M. V. Micieli, and M. M. Ronderos. 2022. “Redescription of immature stages of Culicoides paraensis (Goeldi) (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae), vector of the Oropouche virus.” Zootaxa 5205 (3): 249–264. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5205.3.4

Benitez, A. J., M. Alvarez and L. Perez. 2024. “Oropouche Fever, Cuba, May 2024.” Emerging Infectious Diseases Volume 30, Number 10. Preprint. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3010.240900

Blanton, F. S., and W. W. Wirth. 1979. “The sand flies (Culicoides) of Florida (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae).” Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas Volume 10. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Gainesville, FL. 204 pp.

Blosser, E. M., B. L. McGregor, and N. D. Burkett-Cadena. 2024. A photographic key to the adult female biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae: Culicoides) of Florida, USA.” Zootaxa 5433 (2): 151–182. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5433.2.1

Borkent, A., and G. R. Spinelli. 2000. Catalog of the New World biting midges south of the United States of America (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). Contributions on Entomology, International. 4(1). 107 pp.

Harrup, L. E., M. A. Miranda, and S. Carpenter. 2016. “Advances in control techniques for Culicoides and future prospects.” Veterinaria Italiana 52 (3–4), 247–264. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.741.3602.3

Hribar, L. J. 2008. “An unusual larval habitat for Culicoides arboricola (Root & Hoffman) (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in the Florida Keys, USA.” Russian Entomological Journal 17 (1): 71–72.

Humphreys, J. G., and E. C. Turner. 1973. “Blood-Feeding Activity of Female Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae).” Journal of Medical Entomology 10 (1): 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/10.1.79

Lamberson, C., C. D. Pappas, and L. G. Pappas. 1992. “Pupal Taxonomy of the Tree-Hole Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in Eastern North America.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 85 (2): 111–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/85.2.111

LeDuc, J. W., and F. P. Pinheiro. 2019. “Oropouche Fever.” In The Arboviruses (pp. 1–14). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429289170-1

Linley, J. R., and S. Jordan. 1992. “Effects of ultra-low volume and thermal fog malathion, scourge and naled applied against caged adult Culicoides furens and Culex quinquefasciatus in open and vegetated terrain.” Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 8 (1): 69–76.

Linley, J. R., R. E. Parsons, and R. A. Winner. 1988. “Evaluation of ULV naled applied simultaneously against caged adult Aedes taeniorhynchus and Culicoides furens.” Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 4 (3): 326–332.

McGregor, B. L., T. Stenn, K. A. Sayler et al. 2019. “Host use patterns of Culicoides spp. biting midges at a big game preserve in Florida, USA, and implications for the transmission of orbiviruses.” Medical and Veterinary Entomology 33 (1): 110–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12331

Mullen, G. R., and C. S. Murphree. 2019. “Biting Midges (Ceratopogonidae).” In Medical and Veterinary Entomology (pp. 213–236). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814043-7.00013-3

Murphree, C. S., and G. R. Mullen. 1991. “Comparative larval morphology of the genus Culicoides Latreille (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in North America with a key to species.” Journal of Vector Ecology 16:269e399.

Pinheiro, F. P., A. P. Travassos da Rosa, and J. F. Travassos da Rosa. 1981. “Oropouche Virus. I. A review of Clinical, Epidemiological, and Ecological Findings.” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 30 (1): 149–160. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.149

Snow, W. E. 1955. “Feeding Activities of Some Blood-Sucking Diptera with Reference to Vertical Distribution in Bottomland Forest.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 48 (6): 512–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/48.6.512

Snow, W. E., E. Pickard, and C. M. Jones. 1958. “Observations on the Activity of Culicoides and other Diptera in Jasper County, South Carolina.” Mosquito News 18 (1): 18–2.

Wirth, W. W., and M. L. Felippe-Bauer. 1985. “The neotropical biting midges related to Culicoides paraensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae).” Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 84:551–65. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761989000800096