The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The alfalfa leaf-cutter bee (Megachile rotundata) is a solitary, cavity nesting bee, native to Eurasia. It was introduced accidentally to the United States in the 1940s (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011), where it is believed to have first arrived as a pre-pupae in tunnels within wooden pallets incoming from the Mediterranean (Goettel, 2008). Alfalfa leaf-cutter bees are polylectic bees, which means they forage on many different plants (Yajcaji, 2011). They are used for pollination services in over 70,000 hectares in North America (Kemp and Bosch, 2000), where their pollination is recognized to increase the alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) seed production in the northwestern United States and Central Canada by 50% (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). The alfalfa leaf-cutter bee is also used for pollination services on canola, carrots, and cranberries in field cages (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). Given that it is considered a gregarious species, females tolerate other females’ nests in the close vicinity, making the alfalfa leaf-cutting bee commercially manageable (Goettel, 2008; Figure 1). Females provide all food needed for their offspring until they reach adulthood (Peterson and Roitberg, 2006).

Credit: Rob Snyder (support@beeinformed.org), UC Davis, used with permission

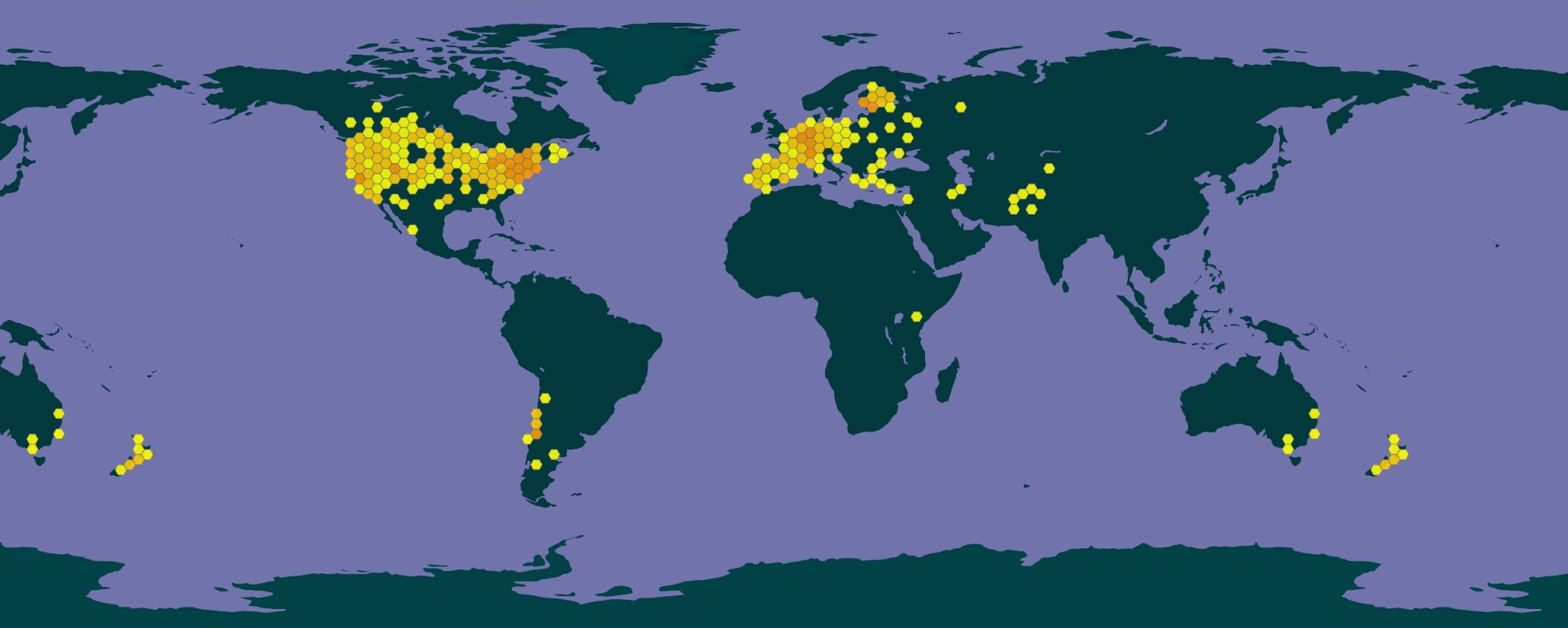

Distribution

Alfalfa leaf-cutter bees are originally from southwestern Asia and southeastern Europe. It is widely distributed in the United States, Canada (Osterman et al., 2021), Australia (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 201), New Zealand, Sweden, Chile, and Argentina. It was first introduced in South America in the 1970s for alfalfa pollination (Alvarez et al., 2012; Figure 2).

Credit: Accessed via GBIF (Feb 2025) https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei

Description

Like all Hymenoptera, alfalfa leaf-cutter bees are holometabolous insects (Bennett et al. 2015), meaning they undergo complete metamorphosis.

Eggs

Eggs take two to three days to hatch. Each egg is deposited in a linear cell and provided with pollen and nectar (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011).

Larvae

Larvae are grub-like, legless, and white. Larvae have chewing mouth parts (Texas A&M Agrilife Extension n.d.).

Adults

The body of adult alfalfa leaf-cutter bees is cylindrical and robust, mostly black with white bands on the abdomen (Will et al., 2020). They are similar in appearance to honey bees, but instead of carrying the pollen on the hind legs, alfalfa leaf-cutter bees carry pollen on the bottom of their abdomen (Texas A&M Agrilife Extension n.d.). The second tergite (dorsal portion of the abdominal plate) has a distinctive oval-shaped pattern that is used to recognize the species (USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center, 2019; Figure 3). Female leaf-cutter bees have a brush of hair on the abdomen (scopa) to collect and transport pollen (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011; Figure 4). Males are smaller than females (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011).

Credit: USGSBIML Team. USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center

Credit: Nicholas J. Vereecken (Nicolas.vereecken@ulb.ac.be), via Flickr, used with permission

Life Cycle

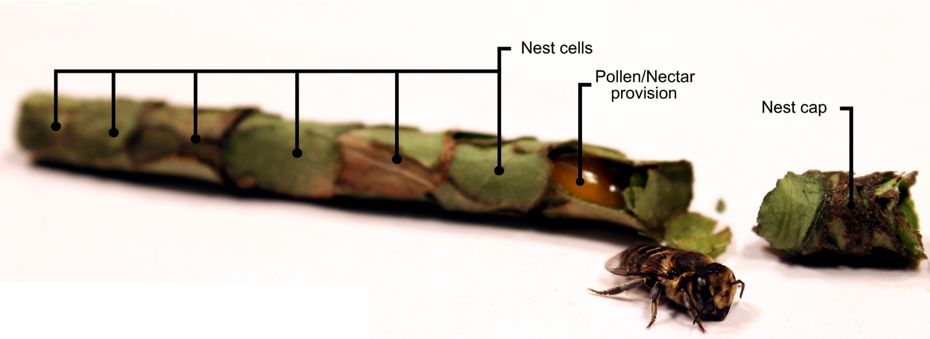

Adult alfalfa leaf-cutter bees emerge and mate in June and July throughout most regions in North America. Females build their nests on natural or artificial existing cavities. The nests are linear cells, which are supplied with pollen and nectar. The egg is deposited on top of the provisioned food and cells are sealed with a cut leaf plug (Kemp and Bosch, 2000; Figure 5). Nests are constructed by females with leaf clippings, with an average of six cells or cocoons per nest (Royauté R et al., 2018). Soft and pliable leaves, such as alfalfa, buckwheat, and rose petals, are the preferred materials for nest construction (Mader, Spivak, Evans, 2010). From the moment the egg is fertilized, it takes from two to three days for the larvae to hatch. Larvae hatch from the egg as a second instar larvae that feeds on the provisions left by the female on the nest (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). The larvae undergo four instars (periods between molts), before spinning a cocoon (Goettel, 2008). Brood overwinters as a non-feeding pre-pupa (larva) (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011) inside a silk-like cocoon (Kemp and Bosch, 2000). The overwintering stage, also called diapause, ends when warm conditions return (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). Adults emerge after the pupal stage, which lasts from three to four weeks. Females mate once and store the sperm, then seek for an existing tunnel or excavate one to deposit the eggs (Goettel, 2008). Alfalfa leaf-cutter bees that emerge first can produce a second generation of bees before warm conditions end (bivoltinism) (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011).

Credit: Royauté R et al. 2018. (bryan.r.helm@vumc.org), used with permission

Management

The management system for alfalfa leaf-cutter bees uses a loose cell system that has four periods or stages: the spring/summer incubation phase, the brood production phase during summer, the cleanup phase during fall and winter and the cell storage phase during winter (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011).

The loose cell system uses grooved wood or polystyrene boards as artificial nesting (Goettel, 2008). This system allows for individual cocooned bees to be removed in fall for storage (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). Each board has thousands of nest cavities (USDA, 2018). A minimum of two empty tunnels per female should be provided (Mader, Spivak, Evans, 2010). The diameter of the grooves on commercial nests is 7 mm (0.28 in) (Rinehart et al., 2024) and the hole length ranges from 95 mm to 150 mm (3.74 in to 5.9 in) (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011).

In early spring, stored brood is artificially incubated (Kemp and Bosch, 2000) at 30°C (86°F) for 25 days and then released in the fields (Snyder, 2014). The day the incubation is completed, usually on day 24 or 25, the bees to be released are brought on the incubation trays to the fields before daylight and placed on shelters for protection from the elements (Argall et al., 1996). Commonly used shelters are 1.8 to 3 m (5.9 to 9.8 ft) high by 2.4 m (7.9 ft) wide and 1.2 m (3.9 ft) deep. Materials used for constructing such structures are plastic, metal and even plywood. Shapes vary from tent-like structures to plastic domes and mobile trailers (Mader, Spivak, Evans, 2010). Nest boxes are placed near the release site, as bees will start mating soon after emerging (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011; Figure 6). Nesting sites can be moved from one location to another at nighttime to ensure females are in the tunnels (Argall et al., 1996).

In alfalfa fields, artificial shelters and empty nesting materials are placed during early summer (Kemp and Bosch, 2000). This must be synchronized with the beginning of the alfalfa flowering season. The nests are left in the fields until fall (USDA, 2018). The cocoons obtained from artificial nesting boxes are stored for the next season (Kemp and Bosch, 2000) at 5°C to 8°C (41°F to 46°F) (Argall et al., 1996) and 50% relative humidity (RH) (Goettel, 2008), after being filtered to remove the non-viable and diseased cocoons (USDA, 2018). Loose pre-pupae cocoons can be stored in bulk in feed sacks (Mader, Spivak, Evans, 2010).

One to two gallons (3.78 to 7.57 liters) per acre are needed for pollination, with one gallon containing around 10,000 individual cocoons (Argall et al., 1996).

Credit: Rob Snyder (support@beeinformed.org), UC Davis, used with permission

Economic Importance

Alfalfa leaf-cutter bees are the second most widely commercially used pollinator, after the western honey bee (Apis mellifera) (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). An estimated 800 million individuals are sold annually in North America (Osterman et al., 2021). Alfalfa leaf-cutter bees are sold in gallons. Each gallon contains approximately 10,000 dormant loose cells (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011). The average cost of 10,000 alfalfa leaf-cutter bees (one gallon or 3.78 liters) is around $100 (NSERC-CANPOLIN, 2024).

The use of the alfalfa leaf-cutter bees in alfalfa fields for pollination services is two to four times more effective than using honey bees for the same purpose (Renzi et al., 2022). They are also used to pollinate canola for hybrid seed production, native legumes, blueberries, and are used for pollination of carrot in field cages (Pitts-Singer and Cane, 2011).

Pests

Alfalfa leaf-cutter bee brood are parasitized by 20 insect species. Chalcid wasps are the most damaging parasitoids. Pteromalus venustus Walker causes the most damage by piercing cocoons and parasitizing the larvae with its ovipositor. Additionally, several cuckoo bees and the brown blister beetle (Nemognatha lutea LeConte) cause important economic damage (Goettel, 2008).

In overcrowded nest sites, leaf-cutter bees can be affected by chalkbrood disease, caused by the fungal pathogen Ascosphaera aggregata (Klinger, Welker, and James, 2021). At one time in the northwestern United States, mortality caused by chalkbrood reached 35% (Huntzinger et al., 2008). The US alfalfa leaf-cutter production collapsed during the 1980s due to a failure to manage the disease appropriately (Mader, Spivak, Evans, 2010). Some farmers in the United States still produce their own bees, but the majority of alfalfa leaf-cutter bees come from suppliers in Canada (USDA, 2018).

X-rays are used to assess the quality of the pre-pupae that have been stored for next season. X-rays distinguish between live, chalkbrood infected larvae, parasitized cells and “pollen balls.” Pollen balls are cells that have been provisioned with food, but no egg was laid, or the larvae died young. Sixty percent of cases where no larvae are found are categorized as pollen balls. Researchers are still investigating the potential causes for pollen balls (USDA, 2018).

Similarly, alfalfa leaf-cutter bees have been found to be sensitive to pesticide exposure, which can be an issue in treated fields (Hayward et al., 2019). Overwintering pre-pupa can also be affected by the dried fruit moth (Vitula edmandsii, Ragonot 1887), flour beetles and grain beetles (Goettel, 2008).

Conclusion

Alfalfa leaf-cutter bees are very important pollinators for some North American crops and are also being reared for pollination in other areas around the world. Learning the proper management of this cavity nesting bee is of vital importance to achieve adequate yields, both for beekeepers and for crop managers.

Selected References

Alvarez LJ et al. 2012. Occurrence of exotic leafcutter bee Megachile (Eutricharaea) concinna (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in southern South America. An accidental introduction? Journal of Apicultural Research 51(3):221–226. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.51.3.01

Argall J et al. 1996. Alfalfa Leafcutter Bees for the Pollination of Wild Blueberries. New Brunswick Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Government of New Brunswick, Canada. Accessed October 2, 2024. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/10/agriculture/content/bees/alfalfa_leafcutterbees.html

Bennett MM et al. 2015. Exposure to Suboptimal Temperatures During Metamorphosis Reveals a Critical Developmental Window in the Solitary Bee, Megachile rotundata. Physiological and biochemical zoology 88.5 (2015): 508–520. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1086/682024

GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. 2023. Megachile rotundata (Fabricius, 1787) in GBIF Secretariat. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei

Goettel MS. 2008. Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee, Megachile rotundata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). In: Capinera, JL (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer, Dordrecht. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_135

Hayward A et al. 2019. The leafcutter bee, Megachile rotundata, is more sensitive to N-cyanoamidine neonicotinoid and butanolide insecticides than other managed bees. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3(11), 1521–1524. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1011-2

Huntzinger, CI et al. 2008. Laboratory Bioassays to Evaluate Fungicides for Chalkbrood Control in Larvae of the Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 101.3 (2008): 660–667. Accessed July 10, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/101.3.660

Kemp WP, Bosch J. 2000. Development and Emergence of the Alfalfa Pollinator Megachile rotundata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 93.4 (2000): 904–911. Accessed September 29, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2000)093[0904:DAEOTA]2.0.CO;2

Klinger E, Welker D, James R. 2021. Presence of Pathogen-Killed Larvae Influences Nesting Behavior of the Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 114.3 (2021):1047–1052. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toab030

Mader E, Spivak M, Evans E. 2010. Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers and Conservationists. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE), Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service (NRAES). Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.sare.org/wp-content/uploads/Managing-Alternative-Pollinators.pdf

McCabe LM et al. 2021. Adult Body Size Measurement Redundancies in Osmia Lignaria and Megachile rotundata (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). PeerJ (San Francisco, CA) 9 (2021): e12344–e12344. Accessed September 29, 2023. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12344

NSERC-CANPOLIN. 2024. Alfalfa leafcutting bee (Megachile rotundata Fab.). Canadian Pollination Initiative. Accessed on February 18, 2025. https://seeds.ca/pollinator/bestpractices/alfalfa_lcb.html#:~:text=Alfalfa%20leafcutting%20bee%20cells%20(cocoons,gallon%20bucket%20(i.e.%2C%20approx

Osterman J et al. 2021. Global Trends in the Number and Diversity of Managed Pollinator Species. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 322 (2021): 107653. Accessed on October 13, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2021.107653

Peterson JH, Roitberg BD. 2006. Impact of Resource Levels on Sex Ratio and Resource Allocation in the Solitary Bee, Megachile rotundata. Environmental Entomology 35.5 (2006): 1404–1410. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/35.5.1404

Pitts-Singer T, Cane JH. 2011. Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee, Megachile rotundata: The World’s Most Intensively Managed Solitary Bee. Annual Review of Entomology 56.1 (2011): 221–237 Accessed September 29, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144836

Renzi JP et al. 2022. Megachile rotundata (Fab.) as a Potential Agro‐environmental Conservation Strategy for Alfalfa Seed Production in Argentina. Journal of Applied Entomology (1986) 146.1–2 (2022): 44–55. Accessed September 29, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12953

Rinehart JD et al. 2024 Nesting cavity diameter has implications for management of the alfalfa leafcutting bee (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 117. 1 (2024): 127–135. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toad207

Royauté R et al. 2018. Phenotypic Integration in an Extended Phenotype: Among‐individual Variation in Nest‐building Traits of the Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee (Megachile rotundata). Journal of Evolutionary Biology 31.7 (2018): 944–956. Accessed September 29, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13259

Stubbs CS, Drummond FA, Yarborough DE. 2007. 300-How to Manage Alfalfa Leafcutting Bees for Wild Blueberry Production. UMaine Extension. The University of Maine. Accessed October 2, 2024. https://extension.umaine.edu/blueberries/300-how-to-manage-alfalfa-leafcutting-bees-for-wild-blueberry-production/#:~:text=On%20average%20bees%20have%20cost,of%20two%20gallons%20per%20acre

Texas A&M Agrilife Extension. N.d. Field Guide to Common Texas Insects: Leafcutting bee. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://texasinsects.tamu.edu/leafcutting-bee/

USDA Agricultural Research Service. 2018. Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee (ALCB). Pollinating Insect-Biology, Management, Systematics Research: Logan UT. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.ars.usda.gov/pacific-west-area/logan-ut/pollinating-insect-biology-management-systematics-research/docs/alfalfa-leafcutting-bee-alcb/#:~:text=In%20order%20to%20mass%2Dproduce,nest%20among%20thousands%20of%20others

USDA Agricultural Research Service. 2018. “Pollen Balls:” A big problem in Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee Production. Pollinating Insect-Biology, Management, Systematics Research: Logan UT. Accessed October 11, 2024. https://www.ars.usda.gov/pacific-west-area/logan-ut/pollinating-insect-biology-management-systematics-research/docs/pollen-balls/

USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center. 2019. Megachile rotundata, male, side. USGSBIML team. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/megachile-rotundata-male-side

Vereecken, NJ. 2020. Megachile rotundata. Nico’s Wild Bees and Wasps. Flickr. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nico_bees_wasps/49945029947

Will K et al., 2020. Field Guide to Insects of California. 2nd edition. University of California Press. Oakland, California.

Yajcaji A. 2011. Megachile rotundata. Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Megachile_rotundata/