The purpose of this article is to inform strawberry growers, Extension agents, the general public, and industry partners about the potential of using banker plants to attract and support the establishment of naturally occurring predatory insects that can help suppress a variety of strawberry arthropod pests.

Abstract

The invasive Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) is currently the most significant pest of strawberries in Florida. Managing this pest is challenging due to its low susceptibility to many commonly used insecticides. As an additional management strategy, we propose using flowering plants (banker plants) to attract naturally occurring predators of thrips, which can help suppress S. dorsalis populations in field strawberries. This article aims to inform strawberry growers, Extension agents, and the public about using banker plants to attract and sustain predatory insects for controlling strawberry pests.

Introduction

Throughout the strawberry growing season (September to March), various arthropod pests can be found infesting strawberries. Currently in Florida, the arthropod pest complex of strawberries is composed of mostly thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) such as Frankliniella occidentalis Pergande (western flower thrips), Frankliniella bispinosa Morgan (Florida flower thrips) (Funderburk 2009; Strzyzewski et al. 2021), and the invasive Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood commonly known as chilli thrips (Lahiri et al. 2022). Additionally, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Trombidiformes: Tetranychidae) is also commonly found infesting strawberries especially later in the season. However, since 2015, S. dorsalis has emerged as the most significant pest of strawberries in Florida (Kaur et al. 2022; Lahiri 2023; Lahiri et al. 2020). To manage chilli thrips, many strawberry growers heavily rely on insecticides, a practice that has resulted in reduced effectiveness of these products (Kaur et al. 2023).

As an additional strategy to manage chilli thrips, many growers perform augmentative releases of commercially available predatory mites, especially Amblyseius swirskii Athias-Henriot and Neoseiulus cucumeris Oudemans (Mesostigmata: Phytoseiidae) into their fields (Lahiri 2023). This has to be done at least twice during the strawberry season, which adds to the overall expenses incurred by the growers. Nonetheless, there is a possibility of recruiting naturally occurring predators that could suppress S. dorsalis populations in the field. These natural enemies can be used effectively in pest management if they have a suitable habitat in which to thrive. Introducing banker plants alongside main crops (strawberries) can help provide the necessary habitat for these beneficial insects.

Banker Plants

Banker plants are plants purposefully grown alongside agricultural crops (such as strawberries) that provide essential food resources, refugia, and reproduction sites for naturally occurring predators, and thus effectively support the establishment of beneficial predator populations. The banker plant system can be considered an open insect rearing system that involves rearing natural enemies (beneficial insects) on plants directly in the fields. This approach enables predators to establish themselves and effectively control pest populations when they begin to increase (Huang et al. 2011). Additionally, banker plants can offer alternative food sources (such as pollen and nectar) to the released predators, particularly during periods of low pest populations. These food resources can potentially sustain predator populations for longer periods of time, eliminating the necessity for additional releases. Additionally, incorporating flowering plants into agroecosystems enhances plant species diversity, leading to smaller pest populations and reduced crop damage while supporting the diversity and abundance of natural enemies (Letourneau 2011).

A variety of field experiments have demonstrated that flowering plants could be used to attract beneficial predatory insects; for example, sweet alyssum Lobularia maritima (L.) Desv. (Brassicales: Brassicaceae) planted alongside squash, Cucurbita pepo L. (Cucurbitales: Cucurbitaceae), attracted natural enemies that suppressed whiteflies Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) (Lopez et al. 2022). Intercropping onions (Allium cepa L., Asparagales: Amaryllidaceae); tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicon L., Solanales: Solanaceae); and eggplants (Solanum melongena L., Solanales: Solanaceae) with marigold, Calendula officinalis L. (Asterales: Asteraceae) improved insect pest management of various pests in these crops (Jankowska et al. 2009; Silveira et al. 2009).

In greenhouse strawberry production, the efficacy of Orius laevigatus Say (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) in management of western flower thrips was improved by the presence of marigolds. Marigolds provided a suitable environment for oviposition, thereby enhancing the predators' performance (Kordestani et al. 2020). Similar observations were reported when sweet alyssum was used as a companion plant to enhance the suppression of Macrosiphum euphorbiae Thomas (Hemiptera: Aphididae) by O. laevigatus (Zuma et al. 2023).

Banker Plant Alternatives for Strawberries

Since 2022, research has been conducted at the University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center to identify potential banker plants that can be used to either attract natural predators of thrips or support populations of predatory mites released for chilli thrips suppression in strawberry fields. The goal is to integrate these banker plants into field strawberry production to help suppress chilli thrips. Currently we have identified four potential plants that could be used as banker plants.

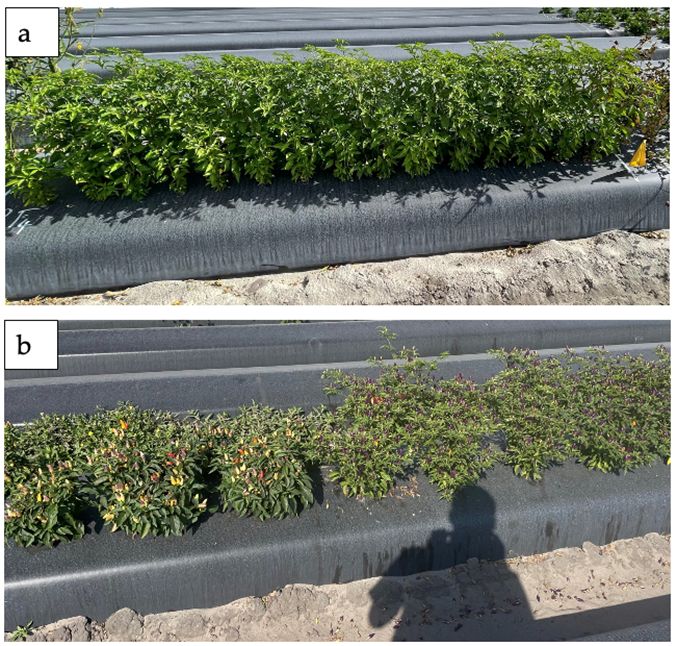

Ornamental pepper; Capsicum annum L. (Solanales: Solanaceae)

Ornamental peppers are herbaceous perennials that thrive in full sun and require moist, well-drained soil. In Florida, they can be planted any time from February through December and can be expected to start flowering between five to six weeks after planting (Gilman et al. 2023). Results from testing this banker plant show that it effectively repels thrips and many other insects (Rakesh et al. 2024). Additionally, it has been demonstrated to support the establishment of predatory mites, particularly A. swirskii, by providing a suitable habitat for the predators to reproduce (Avery et al. 2014).

Credit: Allan Busuulwa, UF/IFAS GCREC

Sweet alyssum; Lobularia maritima (L.)

Sweet alyssum is an annual plant that grows in a mounding form, thrives well in full sun and well-drained soil, and produces clusters of flowers in shades of purple, pink, or white. Blooming usually begins about four weeks after planting and sweet alyssum continues to flower throughout winter and spring. The long flowering periods of sweet alyssum enable it to provide pollen and nectar to many beneficial organisms (Mena et al. 2024), which includes predatory mites released for chilli thrips suppression in strawberries. In our screening study, we observed that sweet alyssum attracted many hoverfly species (Diptera: Syrphidae), ladybugs (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), and parasitoids (Hymenoptera).

Marigold; Tagetes spp. (Asteraceae)

These are annual flowering plants that come in many varieties. French marigolds (Tagetes patula) can survive year-round, while African marigolds (Tagetes erecta) are best suited for spring planting. In our screening study, we observed that the French marigolds attracted primarily minute pirate bugs (Orius pumilio Champion, Hemiptera: Anthocoridae).

Credit: a) Lovely Adhikary, UF/IFAS GCREC; b) Allan Busuulwa, UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: Allan Busuulwa, UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: a) Lovely Adhikary, UF/IFAS GCREC; b) Allan Busuulwa, UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: Lovely Adhikary, UF/IFAS GCREC

Mexican Sunflower; Tithonia rotundifolia (Asterales: Asteraceae)

This annual plant produces vibrant orange to red flowers and grows to a height of four to six feet. It requires full sun and well-drained soil to thrive. Similar to marigolds, we observed that Mexican sunflowers attracted numerous minute pirate bugs. In addition to attracting beneficial insects, these banker plants also attracted pollinators, particularly bumble bees and honeybees. These pollinators play a crucial role in pollinating strawberries, which helps increase the yield.

Credit: Allan Busuulwa, UF/IFAS GCREC

Credit: Sriyanka Lahiri, UF/IFAS GCREC

Limitations of Using Banker Plants

- Marginal pests on banker plants: The presence of various marginal pests on banker plants can give the target pest an advantage by acting as a sink for natural enemies (Heimpel et al. 2003).

- Accidental elimination of banker crops: Banker crops may be accidentally eliminated through mowing or herbicide use. Training farm crews can help prevent this.

- Germination rate information: There may be a lack of information regarding the germination rate of banker crop seeds. Conducting a germination test before planting seeds up to a depth of two inches in soil can address this issue.

Literature Cited

Avery, P. B., V. Kumar, Y. Xiao, C. A. Powell, C. L. McKenzie, and L. S. Osborne. 2014. “Selecting an Ornamental Pepper Banker Plant for Amblyseius swirskii in Floriculture Crops.” Arthropod-Plant Interactions 8 (1): 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-013-9283-y

Funderburk, J. 2009. “Management of the Western Flower Thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Fruiting Vegetables.” Florida Entomologist 92 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.092.0101

Gilman, F. E., T. Howe, W. R. Klein, and G. Hansen. 2023. Capsicum annuum Ornamental Pepper. FPS105. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FP105

Heimpel, G. E., C. Neuhauser, and M. Hoogendoorn. 2003. “Effects of Parasitoid Fecundity and Host Resistance on Indirect Interactions Among Hosts Sharing a Parasitoid.” Ecology Letters 6 (6): 556–566. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00466.x

Huang, N., A. Enkegaard, L. S. Osborne, et al. 2011. “The Banker Plant Method in Biological Control.” Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 30 (3): 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2011.572055

Jankowska, B., M. Poniedziałek, and E. Jędrszczyk. 2009. “Effect of Intercropping White Cabbage with French Marigold (Tagetes patulanana L.) and Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) on the Colonization of Plants by Pest Insects.” Folia Horticulturae 21 (1): 95–103. https://doi.org/10.2478/fhort-2013-0129

Kaur, G., and S. Lahiri. 2022. “Chilli Thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) Management Practices for Florida Strawberry Crops." ENY2076/IN1346. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-in1346-2022

Kaur, G., L. L. Stelinski, X. Martini, N. Boyd, and S. Lahiri. 2023. “Reduced Insecticide Susceptibility among Populations of Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Strawberry Production.” Journal of Applied Entomology 147 (4):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.13108

Kordestani, M., K. Mahdian, V. Baniameri, and A. Sheikhi Garjan. 2020. “Study of Population Dynamics of Orius laevigatus on Green Beans and Marigold as Banker Plants in Greenhouse Strawberry Planting.” Biological Control of Pests and Plant Diseases 9 (1): 16–28. https://doi.org/10.22059/jbioc.2020.292717.281

Lahiri, S. 2023. “Arthropod Pest Management Practices of Strawberry Growers in Florida: A Survey of the 2019–2020 Field Season." ENY2097/IN1391. EDIS, 2023 (1). Gainesville, FL. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-IN1391-2023

Lahiri, S., and B. Panthi. 2020. “Insecticide Efficacy for Chilli Thrips Management in Strawberry, 2019.” Arthropod Management Tests 45 (1): 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/amt/tsaa046

Lahiri, S., H. A. Smith, M. Gireesh, G. Kaur, and J. D. Montemayor. 2022. “Arthropod Pest Management in Strawberry.” Insects 13 (5): 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050475

Letourneau, D. K., I. Armbrecht, B. S. Rivera, J. M. Lerma, E. J. Carmona, M. C. Daza, and A. R. Trujillo. 2011. “Does plant diversity benefit agroecosystems? A synthetic review.” Ecological Applications 21 (1): 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-2026.1

Lopez, L., and O. E. Liburd. 2022. “Can the introduction of companion plants increase biological control services of key pests in organic squash?” Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 170 (5): 402–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.13147

Mena, G. T., and J. Gospodarek. 2024. “White Mustard, Sweet Alyssum, and Coriander as Insectary Plants in Agricultural Systems: Impacts on Ecosystem Services and Yield of Crops.” Agriculture 14 (4): 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14040550

Silveira, L. C. P., E. Berti Filho, L. S. R. Pierre, F. S. C. Peres, and J. N. C. Louzada. 2009. “Marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) as an Attractive Crop to Natural Enemies in Onion Fields.” Scientia Agricola 66 (6): 780–787. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-90162009000600009

Strzyzewski, I. L., J. E. Funderburk, J. M. Renkema, and H. A. Smith. 2021. “Characterization of Frankliniella occidentalis and Frankliniella bispinosa (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) Injury to Strawberry.” Journal of Economic Entomology 114 (2): 794–800. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa311

Zuma, M., C. Njekete, K. A. J. Konan, P. Bearez, E. Amiens-Desneux, N. Desneux, and A.-V. Lavoir. 2023. “Companion Plants and Alternative Prey Improve Biological Control by Orius laevigatus on Strawberry.” Journal of Pest Science 96 (2): 711–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-022-01570-9