This publication aims to raise awareness of the updated Florida seed certification requirement for Lettuce mosaic virus, the pathogen, and the disease the pathogen causes, also called lettuce mosaic virus (LMV). The State of Florida mandates that all lettuce seeds sold and used in the state must be tested and certified as LMV-free (i.e., zero infected per 30,000 seeds tested for LMV). This publication is directed to state and county Extension faculty, crop consultants, current and potential lettuce producers, seed companies, and home gardeners who grow lettuce in Florida.

Introduction

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is among the top ten most consumed vegetables in the United States. The acreages of harvested lettuce increased significantly from 2017 to 2022, from 325,000 to 367,000 acres nationwide (USDA NASS 2017 and 2022). In Florida, the third-largest lettuce-producing state after California and Arizona, the acreage increased from 9,300 to 11,700 acres during the same period (USDA NASS 2017 and 2022).

Most of the lettuce cultivated in Florida is grown on muck soil in the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) in Palm Beach County. Recently, lettuce production has also expanded to Okeechobee and Hendry counties, where lettuce is grown on sandy soil. According to the USDA census in 2022, there are 224 farms producing lettuce in Florida including small- and large-scale growers (USDA NASS 2022). However, it is unclear whether this data reflects the growing numbers of greenhouse (hydroponic and aquaponic) farms.

The Lettuce mosaic virus (LMV) is one of the most important viruses affecting lettuce production worldwide. This virus is a seed-borne pathogen that can also be transmitted by aphids (Jagger 1921). First detected in Florida lettuce in 1920 (Jagger 1921), LMV severely threatened Florida lettuce production in the 1970s. In 1973, collaborative research efforts led to the implementation of state regulations, which prevented further outbreaks and spread of LMV. Per the Florida Rule, Chapter 5B-38 Lettuce mosaic–lettuce seed certification rule, commercially planted lettuce seeds must be tested for LMV and certified virus-free in the seven main lettuce-producing counties: Lake, Orange, Seminole, Glades, Hendry, Martin, and Palm Beach. In 2023, the seed certification rule was extended statewide to further protect lettuce industry in Florida (FDACS-DPI 2023).

Host Range and Distribution of Lettuce mosaic virus

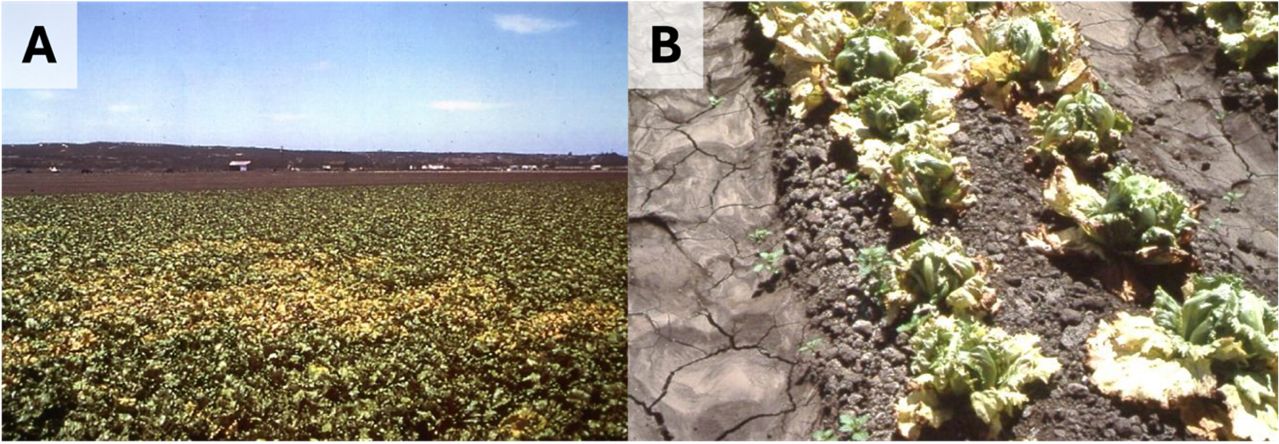

Lettuce mosaic virus is an important viral pathogen that can severely impact lettuce production (Figure 1). This virus belongs to the family Potyviridae and genus Potyvirus, the largest plant-infecting RNA virus genus. There is no cure available for plants infected with LMV.

Credit: Bob Gilbertson, UC Davis, used with permission.

This virus affects species in 20 plant genera across ten families, including Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Solanaceae (German-Retana et al. 2007). In Asteraceae family, LMV infects common lettuce (Lactuca sativa); wildtypes of lettuce including prickly lettuce (L. serriola) and L. virosa; as well as endive and escarole (Cichorium endiva); ornamental safflower (Carthamus tinctorius); and starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis) (German-Retana et al. 2007). This virus can also affect other vegetable hosts, including peas (Pisum spp.); spinach (Spinacia oleracea); and chickpeas (Cicer arietinum) (Dinant and Lot 1992).

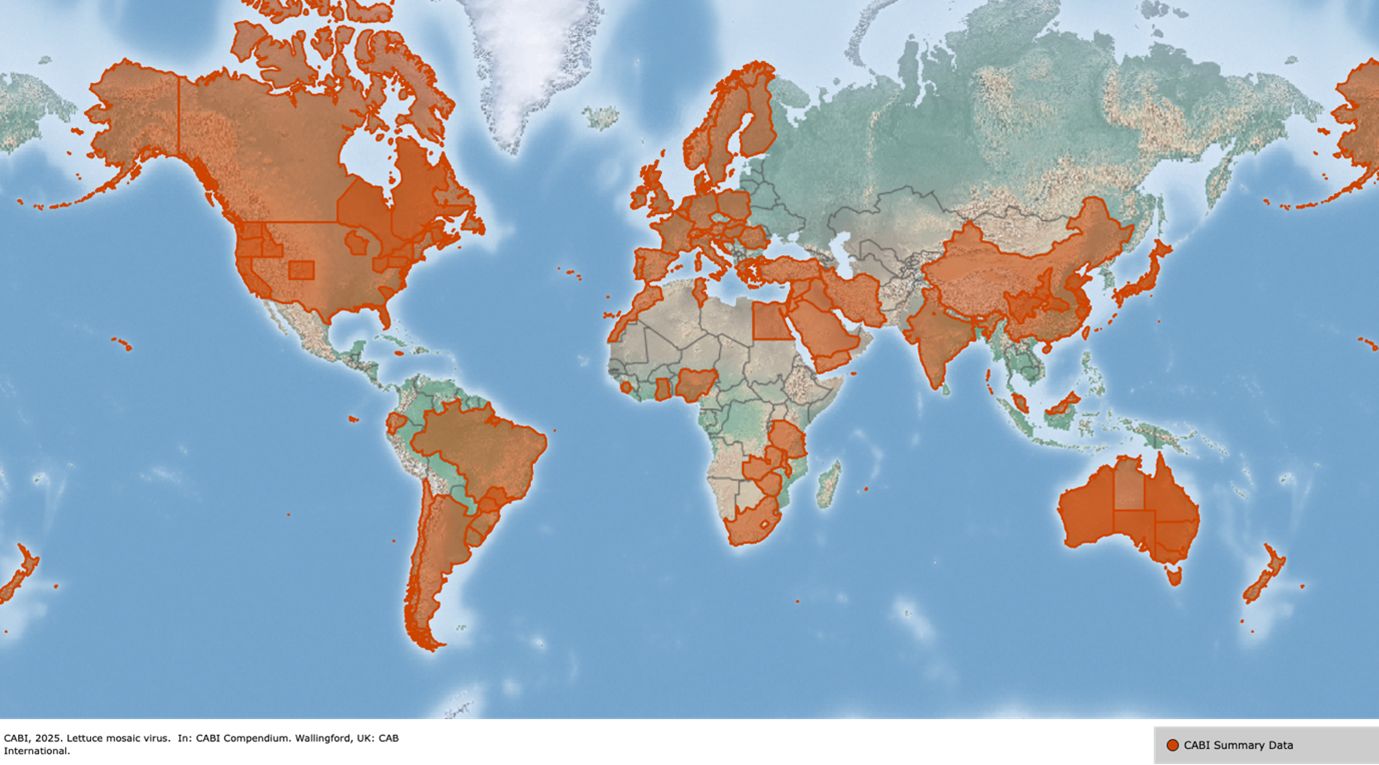

Lettuce mosaic virus was first detected and described in Florida in 1920 in a field of several acres of romaine lettuce of a cultivar Paris White Cos (Jagger 1921). Subsequently, by 1980, LMV was reported in at least 14 countries (Horvath 1980). Currently, the virus is widespread worldwide and can be found everywhere lettuce is commercially grown (Figure 2).

Credit: CABI 2021, used with permission.

Disease Symptoms and Methods Used to Diagnose LMV

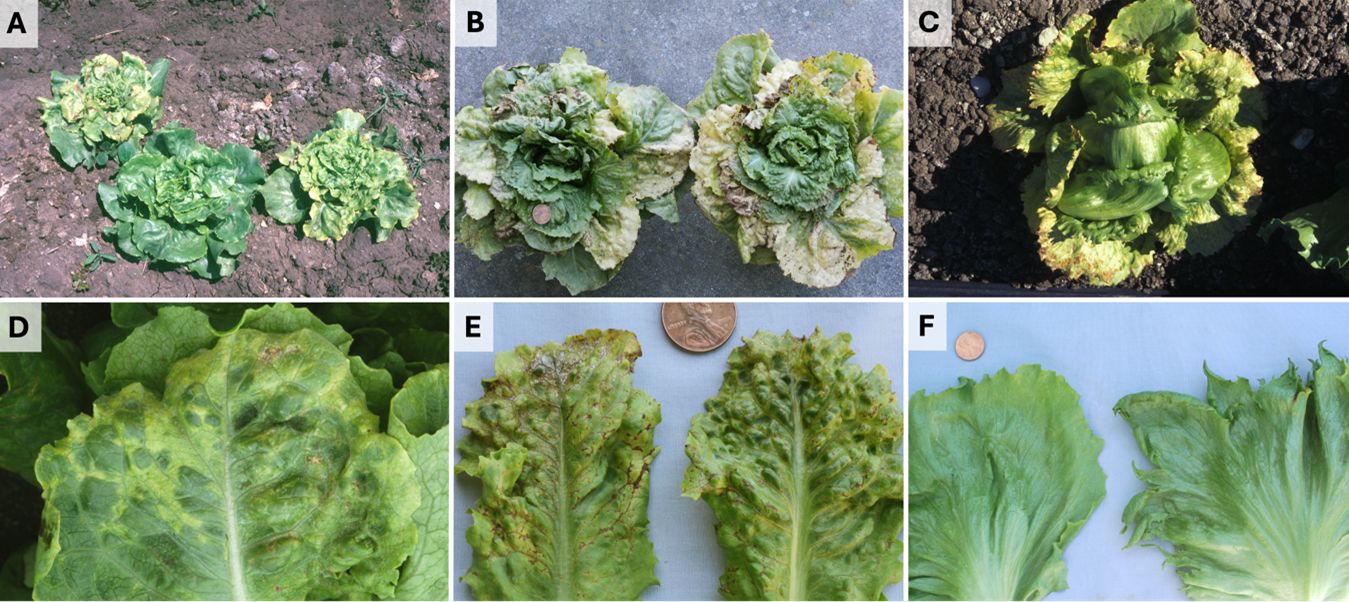

The symptoms of LMV in lettuce can vary between young seedlings and mature plants. Symptoms in the early seedling stage include stunting, necrosis, leaf distortion, plant deformity, chlorosis, mottling that resembles a mosaic, and accentuated leaf serration (Figure 3). Plants infected at a young age will not form heads, and the leaves may be distorted. The virus can induce a mosaic-mottle symptom in leaves, sometimes as an interveinal mosaic (dark green veins and light green interveinal areas), especially in romaine lettuce. In some cases, brown, necrotic flecks occur on the wrapper leaves. However, other viruses infect lettuce and can induce similar symptoms. Additionally, the expression of LMV symptoms can vary depending on the LMV strain, lettuce type, and time of infection. Because of these complicating factors, LMV cannot be diagnosed based solely on symptoms.

Credit: Steven T. Koike, TriCal Diagnostics, used with permission.

Testing symptomatic plants is necessary for accurate diagnosis. Diagnostic methods such as reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be used in the laboratory, and Agdia ImmunoStrip® for LMV can be used for field testing.

If you suspect LMV infection in your field, contact the Florida Department of Agricultural and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry (FDACS-DPI) (https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Pests-and-Diseases/Plant-Pests-and-Diseases/How-to-Submit-a-Sample-for-Identification) or a UF/IFAS Extension agent or a UF/IFAS Extension vegetable specialist as soon as possible for diagnosis. Additionally, lettuce samples can be submitted to the UF/IFAS Plant Diagnostic Center (https://plantpath.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/plant-diagnostic-center/) as well as Dr. Ozgur Batuman's laboratory (obatuman@ufl.edu) at the UF/IFAS Southwest Florida Research and Education Center (SFREC) and Dr. De-Fen Mou’s laboratory (defenmou@ufl.edu) at the UF/IFAS Everglades Research and Education Center (EREC) for confirmation.

Lettuce mosaic virus Transmission

The LMV can be spread by seeds produced by infected plants (i.e., infected seeds) and aphids. Virus-infected seeds are the most critical factor in LMV disease development, and the source of primary virus spread. Approximately 2%–8% of seeds will be infected if collected from LMV-infected plants (Ryder 1973). All parts of seeds, including the outer pericarp, endosperm, and cotyledons, can contain the virus virion when lettuce plants are infected with LMV. Therefore, it is crucial to test lettuce seeds for LMV to ensure they are LMV-free to prevent virus incidence in the fields.

Secondary spread occurs through aphid transmission; this happens only if there are virus-infected plants within the same area. Non-colonizing aphids (winged aphids that do not stay on lettuce for their lifespan) play an important role, as they tend to fly around and probe multiple plants. In contrast, colonizing aphids (wingless aphids that spend their entire lifespan on lettuce) are less critical for the virus transmission since they rarely move between plants.

Aphids transmit LMV in a non-persistent manner, meaning the virus briefly binds to the aphid’s mouthpart when it feeds on an infected plant, and the virus is released when the aphid probes another plant (Krause-Sakate et al. 2005). In this type of transmission, aphid acquires and inoculates the virus within seconds to minutes, without a latent period. Since LMV has weed hosts, non-colonizing aphid species may acquire the virus when probing infected weeds and subsequently transmit it to lettuce.

Several aphid species were reported to transmit LMV, including the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae); melon aphid (Aphis gossypii); potato aphid (Macrosiphum euphorbiae); black bean aphid (Aphis fabae); and sow thistle aphid (Hyperomyzus lactucae) (Nebreda et al. 2004). These aphid species can be found in Florida.

Germplasm Resistant to Lettuce mosaic virus

Besides using lettuce seeds that are certified LMV-free, another effective method to control the virus is the use of resistant germplasm. Lettuce germplasm, PI 241245, PI 251246, PI 251247, and Gallega, were reported to be resistant to LMV (Ryder 1970). Subsequent efforts were focused on breeding lettuce germplasm resistant to LMV using such resistant germplasm for all lettuce production regions in the United States. For example, some lettuce cultivars developed for Florida were bred with resistance to LMV (Table 1). However, no current breeding efforts are dedicated to LMV, since no outbreaks have been reported in any major lettuce production regions in the Unied States since the 1990s (Raid et al. 1996).

Early Lettuce mosaic virus Control Efforts—Seed Indexing Program, LMV Seed Testing Methods, and Lettuce Mosaic Virus Committee in Florida

In 1961, Florida growers adopted the seed indexing program based on the threshold established in California. Research in California demonstrated that using virus-free seeds was the most effective strategy for reducing LMV infestation in fields (Grogan et al. 1952). Even a small percentage (0.1%) of infected seeds could result in significant LMV outbreaks by harvest. This seed indexing program used the seedling grow-out method to detect infected seed lots. The program was introduced with a strict standard of zero infected seeds per 30,000 as the threshold for commercial seed lots (Grogan 1980).

In 1973, Florida lettuce growers operating near the EAA formed the Florida “Lettuce Mosaic Virus Committee” recognizing the need for coordinated efforts among local growers and researchers to combat LMV (Wisler 1985). Additionally, per growers’ request, the Florida Rule—Lettuce Mosaic Chapter 5B-38—was created by the FDACS-DPI to enforce the seed indexing program to protect the Florida lettuce industry.

Between 1974 and 1984, Florida lettuce growers used the Chenopodium quinoa (common names are Lamb’s quarters or white goosefoot) to detect LMV-infected seeds in seed lots (Figure 4). For this test, C. quinoa plants were grown in a greenhouse and rubbed with a slurry containing lettuce seed that needed to be tested. If the lettuce seeds were LMV infected, C. quinoa would show LMV symptoms. However, this method was time-consuming and limited by environmental factors (Wisler 1985; Madeline Mellinger, Glades Crop Care, Inc. personal communication).

Credit: Madeline Mellinger, Glades Crop Care, Inc., used with permission.

In the 1980s, Dr. Bryce Falk, a former researcher at the UF/IFAS Everglades Research and Education Center in Belle Glade, Florida, concluded that ELISA testing was as sensitive as testing with C. quinoa and that it was faster and required less space (Falk and Purcifull 1983). By 1984, the Florida Lettuce Mosaic Virus Committee officially adopted ELISA as the primary seed indexing method. Seed indexing was conducted by the FDACS-DPI in Gainesville (Wisler 1985) and significantly enhanced LMV management.

Since the adoption of Rule 5B-38 in 1973, only a single small local outbreak of LMV was reported in Florida in 1995 (Raid et al. 1996). Additionally, there have been no reports of LMV incidence in Florida in the past 30 years, indicating the effectiveness of the regulation for LMV management.

Lettuce mosaic virus Seed Certification Rule

The rule 5B-38 by FDACS-DPI has the following subsections: Definition (001); Notice of Quarantine (002); Intrastate Regulation (003); Movement of Regulated Articles (004); Suppressive Area Designation (005); Certification Requirement (006); Required Cultivation Practices (007); Entry of Authorized Representative (008); and the Lettuce Advisory Committee (009).

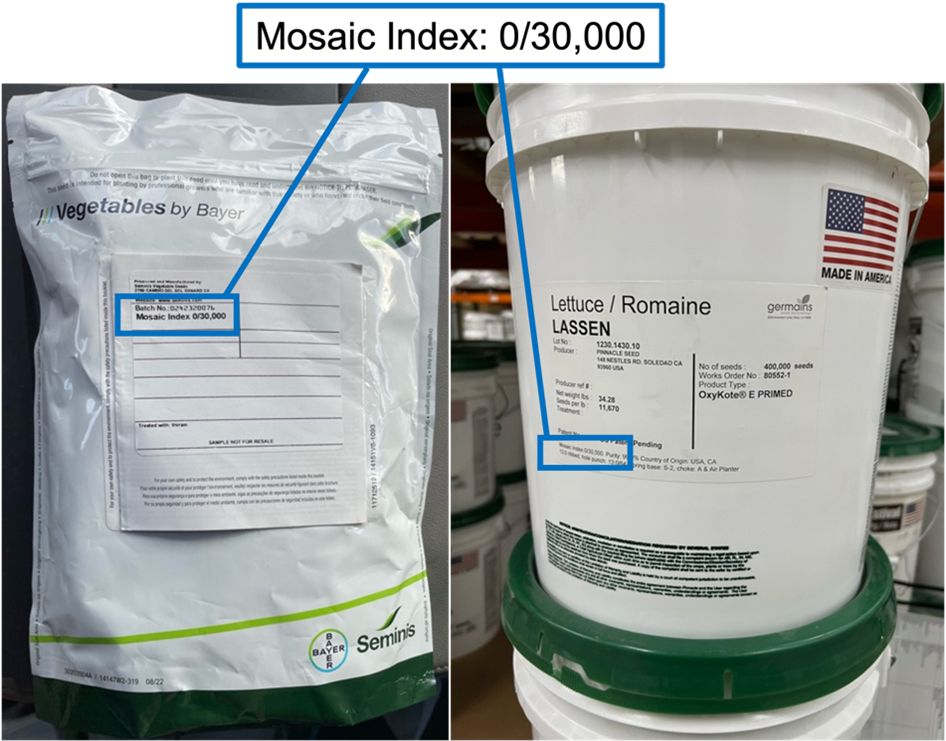

According to the 5B-38.006 Certification Requirement: “(i) Lettuce seed intended for commercial use, being moved, sold, or planted within the state of Florida shall be certified as having been tested by a seed testing facility. Such certification shall be based on the negative testing results of seed tested from at least 30,000 seeds from a designated seed lot; results must show 0 (zero) lettuce mosaic infested seed; certification stating “0 lettuce mosaic in 30,000 seed tested” shall be attached to or printed on the container (Figure 5). (ii) Commercial lettuce plants being moved, sold, or planted within the state must be produced from seed certified in accordance with subsection 5B-38.006(1), F.A.C. (iii) Exemptions: Any person seeking an exemption to plant lettuce plants or seed that do not meet the requirements of subsection (i) or (ii), above, shall apply for an Application and Permit to Move Organisms Regulated by the State of Florida, FDACS-08208, Rev. 01/13, incorporated by reference in Rule 5B-57.004, F.A.C. and may be obtained by emailing to PlantIndustry@FDACS.gov.”

In addition, 5B-38.007 Required Cultivation Practices requires that commercial lettuce plantings must be destroyed by disking, plowing, or other means within ten days of termination of final harvest from the planting. The suppressive area of Rule 5B-38 (5B-38.007 Suppressive Area Designation) originally included the seven counties (Lake, Orange, Seminole, Glades, Hendry, Martin, and Palm Beach) where lettuce was traditionally planted.

Updated Lettuce mosaic virus Seed Certification Rule, 2023

Over the years since the first seed certification rule, the Florida lettuce industry expanded across the state, so the Lettuce Advisory Committee (formerly known as the Lettuce Mosaic Virus Committee) requested the rule be revised. As a result, in 2023, section 5B-38.005 Suppressive Area Designation was updated to include all 67 counties in Florida as LMV suppressive areas. The 5B-38.006 certification requirement remained the same. The updated Rule 5B-38 can be accessed via the FDACS website: https://www.flrules.org/gateway/ChapterHome.asp?Chapter=5B-38.

Today, lettuce germplasm from major seed companies is certified with zero LMV infection in 30,000 seeds tested, with a Mosaic Index of 0/30,000 (Figure 5). Additionally, lettuce seeds used in the UF/IFAS lettuce breeding program are certified as a part of a collaborative effort with the Florida Lettuce Advisory Committee.

Credit: Matt Bardin, Seminis Vegetables by Bayer (left); Ethan Basore, TKM Bengard Farms, LLC (right). Used with permission.

Remarks

- Lettuce mosaic virus causes viral disease in lettuce crops reported worldwide.

- Using certified seed is the most effective practice for preventing LMV outbreaks. The last outbreak in Florida occurred over 30 years ago.

- The state of Florida mandates that all lettuce seeds must be tested and certified as LMV-free.

- Rule 5B-38, issued by the FDACS-DPI, has been updated to include all 67 counties in the state.

- Lettuce samples can be submitted to the UF/IFAS Plant Diagnostic Center for LMV diagnostics.

- For further information on this rule, please contact vegetable and horticulture county or statewide UF/IFAS Extension faculty.

References

CABI. 2021. Lettuce Mosaic Virus (Lettuce Mosaic). In CABI Compendium. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.1079/cabicompendium.30269

Dinant, S., and H. Lot. 1992. “Lettuce Mosaic Virus.” Plant Pathology 41:528–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.1992.tb02451.x

Falk, B. W., and D. E. Purcifull. 1983. “Development and Application of an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Test to Index Lettuce Seeds for Lettuce Mosaic Virus in Florida.” Plant Disease 67:413–416. https://doi.org/10.1094/PD-67-413

Florida Department of Agricultural Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry (FDACS–DPI). “Rule Chapter: 5B-38. Chapter Title: Lettuce Mosaic.” Florida Administrative Code & Florida Administrative Register. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.flrules.org/gateway/ChapterHome.asp?Chapter=5B-38

German-Retana, S., J. Walter, and O. Le Gall. 2008. “Lettuce Mosaic Virus: From Pathogen Diversity to Host Interactors.” Molecular Plant Pathology 9 (2): 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00451.x

Grogan, R. G. 1980. “Control of Lettuce Mosaic with Virus Free Seed.” Plant Disease 64 (5): 446–449.

Grogan, R. G., J. E. Welch, and R. Bardin. 1952. “Common Lettuce Mosaic Control Use of Mosaic-Free Seed Effectively Reduced the Seed-Born[e] Aphid-Transmitted Disease in Large-Scale Field Planting.” California Agriculture. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://californiaagriculture.org/article/114515-common-lettuce-mosaic-control-use-of-mosaic-free-seed-effectively-reduced-the-seed-born-aphid-transmitted-disease-in-large-scale-field-plantings

Horvath, J. 1980. “Viruses of Lettuce. I. Natural Occurrence—A Review.” Acta Agronomica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 29:62–67.

Jagger, I. C. 1921. “A Transmissible Mosaic Disease of Lettuce.” Journal of Agricultural Research 10:737–741.

Krause-Sakate, R., E. Redondo, F. Richard-Forget, et al. “Molecular Mapping of the Viral Determinants of Systemic Wilting Induced by a Lettuce mosaic virus (LMV) Isolate in Some Lettuce Cultivars.” Virus Research 19:175–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2004.12.001

Nebreda, M., A. Moreno, N. Pérez, I. Palacios, V. Seco-Fernández, and A. Fereres. 2004. “Activity of Aphids Associated with Lettuce and Broccoli in Spain and Their Efficiency as Vectors of Lettuce mosaic virus.” Virus Research 100:83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.016

Raid, R. N., R. T. Nagata, and L. G. Brown. 1996. “A Recent Outbreak of lettuce mosaic potyvirus in Commercial Lettuce Production in Florida.” Plant Disease 80:343. https://www.apsnet.org/publications/plantdisease/backissues/Documents/1996Abstracts/PD_80_0343C.htm

Ryder, E. J. 1970. “Screening for Resistance to Lettuce Mosaic.” HortScience 5 (1): 47–48. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.5.1.47

Ryder, E. J. 1973. “Seed Transmission of Lettuce mosaic virus in Mosaic Resistant Lettuce.” Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 98 (6): 610–614.

Sandoya, G., and H. Lu. 2020. Evaluation of Lettuce Cultivars for Production on Muck Soils in Southern Florida. HS1225. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/HS1225

Simons, J. N., and T. A. Zitter. 1980. “Use of Oils to Control Aphid-Borne Viruses.” Plant Diseases 64 (6): 542–546.” Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.apsnet.org/publications/PlantDisease/BackIssues/Documents/1980Articles/PlantDisease64n06_542.PDF

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. “USDA NASS, Quick States.” Accessed October 04, 2024. https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/AAF3F3CC-017B-36D8-B14E-D0CB5A83B374

Wisler, G. C. 1985. “Lettuce mosaic virus.” Florida Department of Agricultural Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry FDACS–DPI Plant Pathology Circular. No. 275. Accessed October 25 2024. https://www.fdacs.gov/content/download/11281/file/pp275.pdf

Table 1. List of Florida lettuce germplasm reported to be resistant to LMV (Sandoya and Lu 2020). These cultivars are not currently used for production in Florida but rather could be used as sources of resistance to LMV when needed.

*Susceptible: Can be infected by LMV; Resistant: Unlikely to be infected by LMV; Tolerant: While it can be infected by LMV, lettuce can still grow, and production is not affected.