Introduction

County- and district-level mosquito control programs in Florida use a variety of methods to manage mosquito populations and protect the public by reducing the risk of contracting mosquito-borne diseases. The use of multiple control methods to target multiple life stages of mosquitoes is called integrated mosquito management (IMM). The American Mosquito Control Association considers IMM to be the best way to manage mosquitoes and reduce mosquito-borne disease transmission (AMCA 2021). The components of an IMM program, which include community engagement, surveillance, source reduction, larval and adult mosquito management through biological control and the application of targeted insecticides, and monitoring for insecticide resistance, are not always visible to the public. Public perception of mosquito control programs is sometimes negative, especially when people do not have a good understanding of the behind-the-scenes steps of IMM. Therefore, the purpose of this publication is to educate Florida residents about mosquito control programs in Florida by providing an overview of the regulation of these programs and a full understanding of the IMM strategies they practice.

Regulation of Mosquito Control Programs in Florida

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) regulates county- and district-level mosquito control programs in Florida, and over 65 FDACS-approved mosquito control programs exist in the state. These programs are subject to the regulations listed in Chapter 388 Florida Statutes (F.S.), also known as the Mosquito Control Law, and Section 5E-13.036 of the Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.). In addition to defining the duties of mosquito control programs, Chapter 388 F.S. mandates that mosquito control activities in the state be performed “in a manner consistent with protection of the environmental and ecological integrity of all lands and waters throughout the state” (Florida Department of State 2014). Per Section 5E-13.036 F.A.C., pesticide applicators in these programs must be certified or directly supervised by a supervisor with a Public Health Pest Control license. These licenses are regulated by FDACS and require continuing education units to renew every four years. Section 5E-13.036 F.A.C. also requires that before an adulticide (an insecticide that kills adult mosquitoes) can be applied by a mosquito control program, the program must detect an increase in the mosquito population above a predetermined baseline, collect more than 25 mosquitoes in a single trap, or collect more than five mosquitoes per hour at dusk or dawn.

Integrated Mosquito Management Strategies Used by Florida Mosquito Control Programs

Community Education and Engagement

Many mosquito control programs educate residents about the integrated mosquito management practices that these programs perform and how residents can reduce their risk of mosquito-borne diseases. Because mosquito eggs need water to hatch and immature mosquitoes need water to survive, mosquito control programs frequently encourage community members to practice source reduction, which is the emptying of water from containers around their homes where mosquito eggs can be laid and immature mosquitoes can develop. Information is often distributed through social media pages, websites, radio interviews, presentations, and booths or trailers at community events. For example, a mosquito control program’s booth at a community event may provide attendees with opportunities to view mosquitoes up close under a microscope, observe Gambusia mosquitofish used for biological control, and learn about the active ingredients in mosquito repellents recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Figure 1).

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Surveillance

Mosquito control programs collect environmental, mosquito population, and mosquito-borne virus surveillance data to guide operational activities. Environmental surveillance is conducted to collect data on environmental factors, like temperature, rainfall amounts, and tide levels, that influence mosquito numbers. Environmental surveillance data can be obtained from weather stations, rain gauges, and other tools.

As mentioned above, section 5E-13.036 F.A.C. mandates that a mosquito control program must conduct mosquito population surveillance before making an adulticide application. Mosquito population surveillance data can be collected using mosquito traps, field inspections, and resident reports. Various types of mosquito traps are used to collect data on mosquito species and their abundance in a specific area. Many Florida mosquito control programs use CDC miniature light traps to monitor adult female mosquitoes seeking blood meal hosts (Lloyd et al. 2018). The light is used as an attractant for mosquitoes, but the traps can be operated with the light off. Many mosquito control programs use carbon dioxide (either in the form of dry ice or bottled gas) as an additional mosquito attractant for CDC miniature light traps (Figure 2).

Credit: Eva A. Buckner, UF/IFAS

In addition to adult mosquito surveillance, mosquito control programs also conduct larval mosquito surveillance. Using a tool called a dipper, which is a white plastic cup attached to stick or telescoping rod, mosquito control inspectors collect, identify, and count mosquito larvae in bodies of water like swamps, salt marshes, and roadside ditches to determine the need for larvicide treatments (Figure 3). Mosquito surveillance data can also come from the public. An increase in customer requests in a specific area indicates a need for inspection to verify that the complaints are mosquito related. If mosquitoes are confirmed at or above threshold level in a given area, a treatment may be scheduled for that area.

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

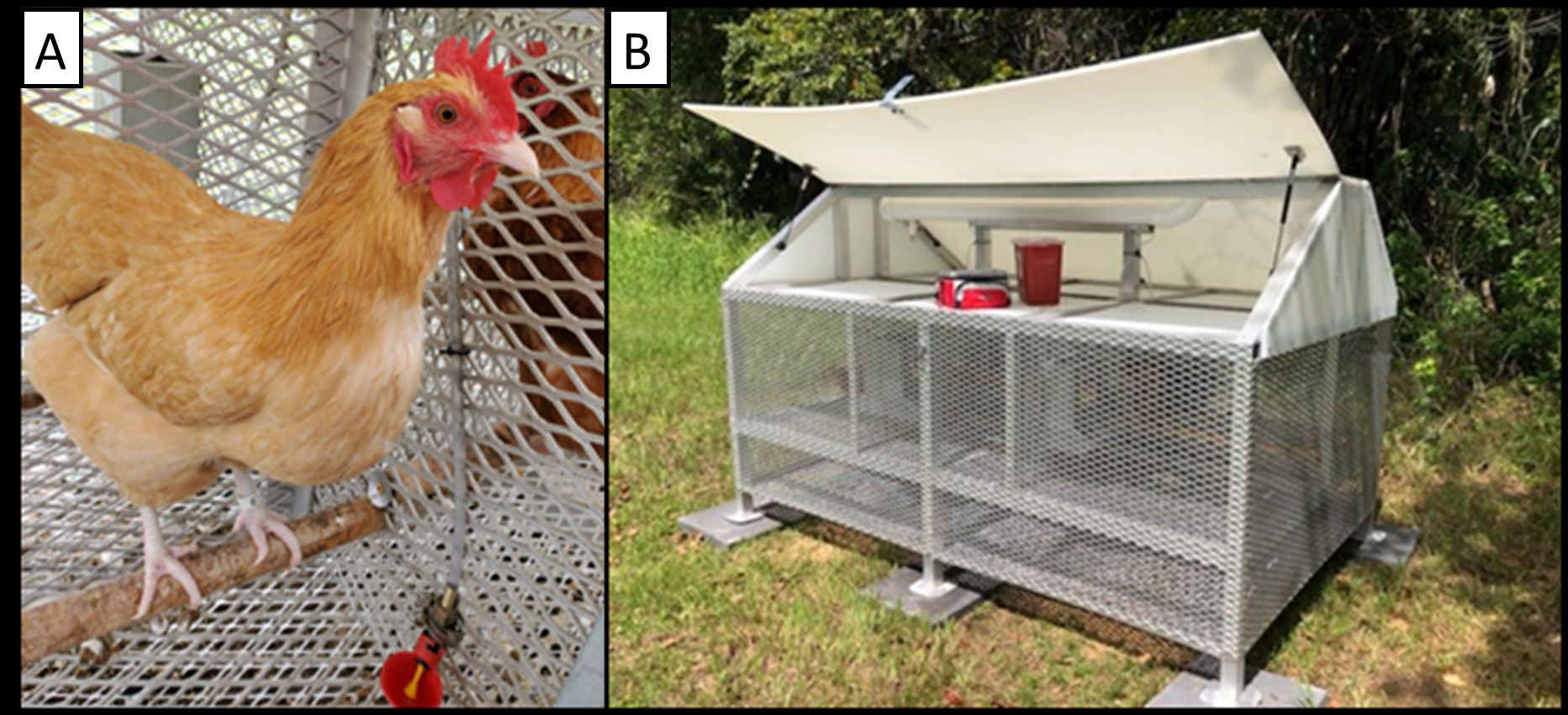

Also, approximately one-third of mosquito control programs in Florida collect valuable data on endemic mosquito-borne virus transmission occurring regularly in an area using sentinel chickens (Lloyd et al. 2018; Figure 4). Blood samples are taken from these chickens generally each week and sent to a lab for antibody testing to detect the presence of endemic mosquito-borne viruses like West Nile virus, Eastern equine encephalitis virus, and St. Louis encephalitis virus. Endemic mosquito-borne viruses circulate between wild birds and mosquitoes, and people become infected with these viruses when mosquitoes feed on infected wild birds and then bite people. Referred to as dead-end hosts, chickens do not become sick from these viruses and do not spread the virus to other mosquitoes but do develop antibodies to them, making them a helpful tool for surveillance of endemic mosquito-borne virus transmission levels in an area. When surveillance data indicates an increase in virus activity in an area, a mosquito control program can target habitats of the specific mosquito vectors that transmit these pathogens to reduce risk of transmission to people, horses, and other dead-end hosts.

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Source Reduction

Some mosquito species are closely associated with humans and take advantage of manmade, water-filled containers like rainwater storage barrels and bird baths, as well as discarded or abandoned items like tires, jars, cans, and buckets as immature mosquito habitats. As mentioned above, the act of removing water-holding containers or dumping the water from containers where mosquito eggs can be laid and immature mosquitoes can develop is called source reduction. In suburban and urban areas, source reduction is the most important activity that residents can perform to reduce the likelihood of being bitten by mosquitoes. Due to mosquitoes developing from eggs to adults within approximately a week in Florida, source reduction should be conducted at least weekly. Mosquito control program employees help residents find and empty water-holding containers around homes (Figure 5).

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Discarded or stored tires are a notorious source of container mosquitoes, because they can hold water; are awkward, heavy, and difficult to empty completely; and immediately refill with water on the next rainy day. As a part of source reduction, some mosquito control programs collect tires that have been illegally dumped. Additionally, some mosquito control programs may host tire amnesty events or days where waste tires can be disposed of for free to reduce the potential that they will become mosquito habitats (Figure 6).

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Larval and Adult Mosquito Management Through Biological Control and the Application of Targeted Insecticides

Biological Control

Biological control is an important component of integrated pest management that consists of using living organisms to manage pests. The primary biological control agent used by mosquito control programs is the Eastern mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki), which eats mosquito larvae (Lloyd et al. 2018; Figure 7). Unmaintained swimming pools and hot tubs may be stocked with mosquitofish to prevent mosquito production. Other suitable habitats include containers of water that cannot be dumped out routinely, such as small ornamental ponds and fountains without flowing water. Some mosquito control programs offer free mosquitofish to residents upon request. To obtain more information on using mosquitofish and other native fish for mosquito control, please refer to the edis.ifas.ufl.edu publications, “Some Small Native Freshwater Fish Recommended for Mosquito and Midge Control in Ornamental Ponds,” and “Eastern Mosquitofish, Gambusia holbrooki.”

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Application of Targeted Insecticides

Larvicides

Treatment of water bodies or water-holding containers with insecticides to kill immature forms of mosquitoes is referred to as larviciding, and larviciding is vital to a successful IMM program. Most Florida mosquito control programs primarily utilize larvicides that are biorational insecticides, which are insecticides of natural origin that have limited or no adverse effects on the environment or beneficial organisms (Lloyd et al. 2018, Ware 1989). The biorational larvicide active ingredients used by Florida mosquito control programs include Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies israelensis (B.t.i.), a bacterium found naturally in soil, and methoprene, an insect growth regulator mimic (Lloyd et al. 2018). Typically, larvicide applications occur during the day and are made directly to the water where larvae are present or in dry areas where flooding and mosquito egg hatching is anticipated. Larviciding products are available in a variety of materials such as granular, liquid, tablets, and water-soluble packets.

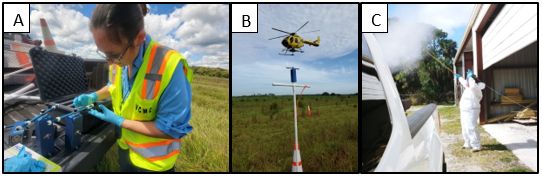

Mosquito control personnel typically apply larvicides to small, accessible larval habitats using backpack sprayers. Larvicides may be applied to larger water bodies containing larvae or areas that cannot be easily treated on foot using equipment attached to ATVs, trucks, boats, helicopters, or airplanes (Figure 8). This equipment allows large areas to be treated quickly and efficiently. For example, ditches and storm drains along roadsides may be treated using right-hand-steered vehicles to allow larvicide applicators to safely move with the flow of traffic.

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Adulticides

When adult mosquito populations reach predetermined thresholds or when the risk of mosquito-borne virus transmission is increased, mosquito control programs will conduct adulticide applications to target actively flying mosquitoes (Lloyd et al. 2018). These applications use ultra-low volume (ULV) spraying equipment that can be mounted on trucks, helicopters, and airplanes (Figure 9). The tiny droplets produced by the equipment are measured and verified to be within product label ranges to ensure the lethal dose is appropriate for the size of a mosquito. Droplets are carried by wind currents and are only effective if they hit mosquitoes actively flying during the application. Application rates are typically less than one ounce of product per acre. Adulticide operations occur before sunrise and after sunset, which is when adult mosquitoes are active. Adulticiding before sunrise or after sunset reduces the risk of exposure to non-target insects like bees and butterflies, which are less likely to be flying at night. When adulticides are applied using label directions, they do not harm people, pets, or the environment (CDC 2023).

Credit: Eva Buckner, UF/IFAS

Adulticide application equipment, such as truck-mounted ULV sprayers and aircraft-mounted rotary atomizer sprayers, must be checked annually to ensure that they are producing droplets within the droplet size range on adulticide labels. These droplets are collected by spinning collection devices called impingers holding slides or rods (Figure 10). The slides or rods are read under a microscope to count and measure the droplets. This data is used to confirm that adulticides are being applied according to label requirements.

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Insecticide Resistance Monitoring

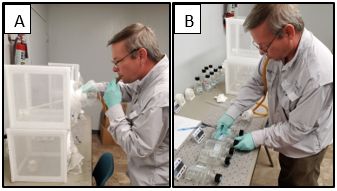

Mosquito control programs can ensure that products remain effective by testing local mosquitoes for insecticide resistance. Local adult mosquitoes can be evaluated in the laboratory for resistance to insecticide active ingredients commonly used in adulticide products using the CDC bottle bioassay (Figure 11). To conduct this test, field-collected mosquito eggs or larvae are reared to adulthood in an insectary, or adult mosquitoes are trapped in the field. Adult mosquitoes are then introduced into glass bottles coated with a small amount of insecticide, and the number of mosquitoes that die at specific intervals over a two-hour period is recorded. The mortality over time of local wild mosquitoes is compared to a susceptible laboratory colony to determine if the local population is susceptible or resistant to the insecticide tested. This data is used to make decisions on which type of adulticide should be used in different areas of the community.

Credit: Miranda Tressler, UF/IFAS

Caged mosquito semi-field trials can also be used to assess the effectiveness of various formulated adulticide products against local mosquitoes (Figure 12). In caged semi-field trials, cages of field-collected local mosquitoes and cages of known susceptible mosquitoes are hung on poles at multiple distances from the adulticide ULV spray path. Rotating slides on each pole capture droplets from the ULV spray cloud, which allows droplet density and mosquito mortality to be evaluated at each distance tested.

Credit: M. J. Tressler, UF/IFAS

Concluding Comments

Florida mosquito control programs strive not only to use all the tools and data available to make informed management decisions but also to follow industry best management practices and IMM strategies. Mosquitoes are targeted in all stages of their life cycle using multiple methods to reduce biting nuisance mosquitoes, the risk of mosquito-borne diseases in communities, and environmental impact. To learn more about the specific services offered by your local mosquito control program, find their contact information on the FDACS website at fdacs.gov. Residents can support the efforts of mosquito control programs by practicing source reduction around homes. Additional information about reducing mosquitoes around homes can be found in the EDIS.IFAS.ufl.edu publication “Mosquitoes and their Control: Integrated Pest Management for Mosquito Reduction around Homes and Neighborhoods.”

Selected References

AMCA. 2021. “Best Practices for Integrated Mosquito Management.” American Mosquito Control Association. Sacramento, CA.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2023 “Adulticides.” May 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/mosquito-control/adulticides.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/mosquito-control/community/adulticides.html Accessed October 13 2025.

Florida Department of State, Florida Administrative Code & Florida Administrative Register. 2014. “Rule Chapter: 5E-13.040 Mosquito Control Program Administration: Criteria for Licensure or Certification of Applicators.” https://www.flrules.org/gateway/ChapterHome.asp?Chapter=5e-13. Accessed 20 April 2024.

Florida Legislature. 2023. “The 2023 Florida Statutes: Title XXIX: Public Health. Chapter 388: Mosquito Control.” Statutes & Constitution :View Statutes :->2023->Chapter 388 : Online Sunshine.

Lloyd, A. M., C. R. Connelly, and D. B. Carlson, Eds. 2018. Florida Coordinating Council on Mosquito Control. Florida Mosquito Control: The state of the mission as defined by mosquito controllers, regulators, and environmental managers. Vero Beach, FL: University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory.

Ware, G. W. 1989. The Pesticide Book, 3rd edition. Thomas Publications, Fresno, California.