Introduction

The cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum Berg (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) arrived in 1989 in the Florida Keys, and this invasive species has become a serious threat to the diversity and abundance of Opuntia cactus in North America (Zimmermann et al. 2001, Stiling 2002). The spread of this moth raises the following major concerns: 1) potential harm to rare opuntioid species (prickly pear and related cacti; members of the subfamily Opuntioideae: Cactaceae), 2) the endangerment of wild opuntioids in the southwestern United States and Mexico and consequent effects on entire desert ecosystems (Perez-Sandi 2001, Soberon et al. 2001, Vigueras and Portillo 2001, Zimmermann et al. 2001), and 3) economic hardship for communities in Mexico that cultivate and sell Opuntia (Soberon et al. 2001, Vigueras and Portillo 2001).

Distribution

A native of South America, Cactoblastis cactorum was introduced from Argentina to Australia in 1925 to control several species of North and South American Opuntia. The effort was highly successful. Later, the cactus moth was introduced into Hawaii, India, South Africa, and a few Caribbean islands for this same purpose. In early 2009, the cactus moth was found and quickly eradicated in Mujeres, Mexico, about 10 miles offshore from Cancun (LSU 2009).

Cactoblastis cactorus has been introduced multiple times to Florida (Marisco et al. 2011). Based on genetic analyses, existing populations probably were likely founded from the introduced Caribbean moth populations (Marisco et al. 2011).

The moth's range continues to expand along both the US Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It now is found as far north as Charleston, South Carolina and as far west as Louisiana (LSU 2009). Cactoblastis cactorum spreads more quickly along the coasts, but inland spread is occurring. The moth was found in Loxahatchee, Palm Beach County, Florida, in June of 1992 by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 24 km inland from the Atlantic Ocean. In 2011, Cactoblastis cactorum was found at the Ordway-Swisher Biological Station in Putnam County, Florida (C. W. Miller).

Please Help! We would like to hear from you if you know of infestations in your area or if you know of the location of Opuntia cactus stands that we could check, particularly if the sites are inland or in front of the leading edge. Please contact: Dr. Stephen Hight, 850-656-9870 Ext. 18.

Description

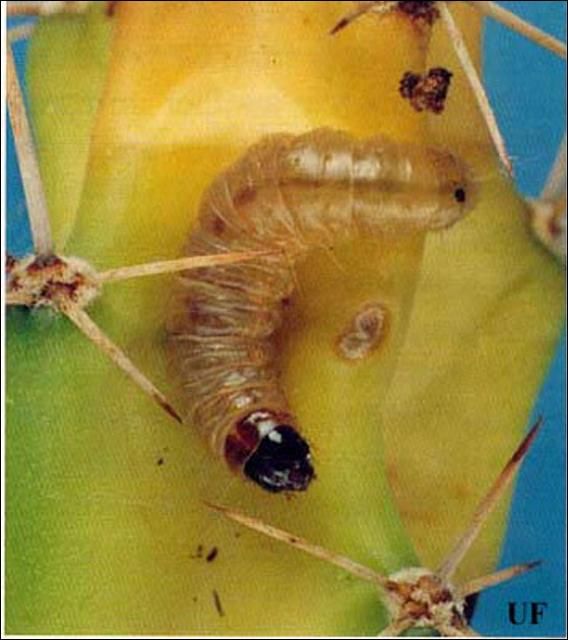

The wing span of the adults ranges from 22- to 35-mm. The forewings are grayish-brown, but whiter toward the costal margin. Distinct black antemedial and subterminal lines are present. Hindwings are white with some gray terminally. Adults of the subfamily Phycitine often appear very similar to one another and are not identified easily because scales of specimens usually are rubbed off; however, genitalia can provide positive identification (Heinrich 1956). The larvae of Cactoblastis cactorum are bright orangish-red with large dark spots forming transverse bands. Mature larvae are 25- to 30-mm-long.

Credit: D. Habeck and F. Bennett, UF/IFAS

Credit: D. Habeck and F. Bennett, UF/IFAS

Key to Florida Phycitine Larvae Associated with Opuntia spp.

1. Larvae gregarious, reddish or bluish-purple, feeding in cladodes (pads). . . . . 2

1'. Larvae solitary, not reddish or bluish-purple, feeding in or on cladodes. . . . . 3

2. Larvae orangish-red with conspicuous dark spots forming transverse bands. . . . (Berg)

3'. Larvae dark. . . . . 4

4. Larvae feeding singly in buds or fruit only. . . . . Ozamia lucidalis (Walker)

4'. Larvae feeding singly on dead tissue but most often feeding on coccids. . . . . Laetilia coccidivora (J. H. Comstock)

Biology

The female Cactoblastis cactorum lays her eggs in the form of a chain; the first egg is attached to the end of a spine or spicule, and succeeding eggs (average 75, and up to 140 or more) are stacked coin-like to form an egg-stick. On eclosion, the larvae crawl from the egg-stick onto the cladode or pad and burrow into it, usually within a few centimeters of the oviposition site. The larvae feed gregariously, moving from cladode to cladode as the food supply is exhausted. During feeding the frass is pushed out of the pad and forms a noticeable heap. Fully developed larvae usually leave the plant and spin white cocoons in the leaf litter, in crevices in the bark of nearby trees, or in similar protected niches. Pupation occasionally occurs in the cladode. The moth emerges, and the cycle is repeated. The length of the life cycle in Florida is unknown but probably shorter than in Queensland, Australia, where there are two generations per year (Dodd 1940).

Credit: D. Habeck and F. Bennett, UF/IFAS

Females show clear egg-laying preferences, selecting Opuntia engelmannii varieties linguiformis and engelmannii over other opuntiods (Jezorek et al. 2010). Interestingly, female egg-laying preferences are not a good predictor of the hosts where larvae perform the best. Jezorek et al. (2010) tested egg-laying preferences of females and offspring performance on 14 opuntioids. They found that Opuntia engelmannii vars. linguiformis and engelmannii ranked seventh and fourth, respectively, for percent emergence and had the second and third longest development times. One of the best hosts for offspring survival and development, Opuntia streptacantha, was one of the least preferred by females. Many factors can lead to a mismatch between female egg-laying preferences and offspring performance; however, in this case the new association of Cactoblastis cactorum with North American Opunia plants is likely a cause. Cactoblastis and its novel hosts have had only a short evolutionary history, and the moth probably has not had a chance to adapt to its new host plants.

Credit: Christine Miller, UF/IFAS

Larvae do not perform well on Opuntia cladodes with a tough skin, such as Opuntia engelmannii variety lindheimeri and Opuntia macrocentra. The larvae appear to have a difficult time burrowing through the tough epidermal layer and get stuck in the secreted mucilage (Jezorek et al. 2010).

Credit: Christine Miller, UF/IFAS

Credit: D. Habeck and F. Bennet, UF/IFAS

Economic Importance

Cactoblastis cactorum, native to South America, was introduced from Argentina into Australia in 1925 to control several North American and South American species of Opuntia. In Queensland, 16 million acres of severely infested land were reclaimed for agriculture by the action of this insect. In fact, the town of Dalby in Queensland, Australia erected a monument in 1965 dedicated to Cactoblastis cactorum for saving the people of Queensland from the scourge of invasive prickly pear cactus. This moth has been an effective control agent of Opuntia spp. in other areas including Hawaii, India, and South Africa. In 1957, it was introduced into the Caribbean, in Nevis, where the control of Opuntia curassavica and other Opuntia spp. was rapid and spectacular (Simmonds and Bennett 1966). Eggs and larvae, or infested cladodes, were sent from Nevis to Montserrat and Antigua in 1962 and to Grand Cayman in 1970 (Bennett et al. 1985). By 1963 the cactus moth had invaded the Lesser Antilles to Puerto Rico (Garcia-Tuduri et al. 1971) and is now present in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and the Bahamas (Starmer et al. 1987).

As mentioned above, the arrival of Cactoblastis cactorum into continental North America is a major concern. It has high potential to destroy native Opuntia spp. In the Florida Keys, Opuntia spinosissima (Martyn) Mill., and Opuntia tricantha (Willdenow). Sweet are rare and are on the "threatened" list. Other native species, such as Opuntia cubensis Britton & Rose, Opuntia stricta Haw., Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Rafinesque, as well as exotic species, either naturalized or grown as ornamentals, in Florida are also at risk. Another concern is the probability that Cactoblastis cactorum will spread west as far as Texas and into Mexico. In these desert regions, wild Opuntia and Cylindropuntia (Engelmann) Kreuzinger species provide food and nesting sites for a variety of wildlife and contribute to soil stability (Chavez-Ramirez et al. 1997). Opuntia is important economically as well. These plants are harvested on over three million hectares in Mexico where they grow naturally (Soberon et al. 2001, Vigueras and Portillo 2001). In addition, 250,000 hectares of Opuntia and Nopalea species are cultivated for human and livestock food, for fuel, and for manufacturing. These plants are valued in Mexico at over 80 million dollars annually (Soberon et al. 2001). The devastating affect of Cactoblastis cactorum on cactus growth is well known.

Management

No satisfactory method of chemical control of Cactoblastis cactorum is known. The widespread use of pesticides is not recommended because of the occurrence of rare and endangered fauna such as Schaus swallowtail, Florida leaf-wing, and Bartram's hairstreak butterflies. Similarly, inundative releases of egg parasites such as Trichogramma could have an adverse affect on other desirable Lepidoptera.

Efforts to control this invasive species have been focused on containing the spread via quarantine, as well as development of fungal, bacterial, parasitoid, and nematode biological control agents. Sterile insect technique is also a possible management tool (Hight et al. 2005). In its native habitat in South America several natural enemies are known, including Apanteles alexanderi Brethes (Braconidae), Phyticiplex doddi (Cushman) and Phyticiplex eremnus (Porter) (Ichneumonidae), Brachymeria cactoblastidis Blanchard (Chalcididae), and Epicoronimyia mundelli (Blanchard) (Tachinidae). The host range of these natural enemies would have to be determined before the release of any of these for the control of Cactoblastis cactorum could be approved.

Surveys between July 2008 and December 2009 revealed that egg-sticks of Cactoblastis cactorum in north Florida are attacked by egg parasitoids in the genus Trichogramma: Trichogramma pretiosum Riley, Trichogramma fuentesi Torre, and an additional unidentified Trichogramma species belonging to the Trichogramma pretiosum group. Unfortunately, Paraiso et al. (2011) found that only 0.2% of eggs are destroyed naturally by these parasitoids. However, with laboratory rearing and inundative releases, Trichogramma wasps could be integrated in the current pest management system.

Selected References

Bennett FD, Cock MJW, Hughes IW, Simmonds FJS, Yaseen M. [Cock MJW. (ed.)]. 1985. A review of biological control of pests in the Commonwealth Caribbean and Bermuda up to 1982. Commonwealth Institute of Biological Control Technical Committee 9. 218 pp.

Brown RL, Lee S, MacGown JA. (July 2009). Video of the dissection of the male genitalia of the cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum. Cactus Moths and Their Relatives (Pyralidae: Phycitinae). (22 August 2012).

Chavez-Ramirez F, Wang XG, Jones K, Hewitt D, Felker P. 1997. Ecological characterization of Opuntia clones in South Texas: Implications for wildlife herbivory and frugivory. Journal of the Professional Association for Cactus Development 2: 9–19.

Dodd AP. 1940. The biological campaign against prickly-pear. Commonwealth Prickly-pear Board Bulletin, Brisbane, 177 pp.

Garcia-Tuduri, Martorell JC, Medina Gaud S. 1971. Geographical distribution and host plant list of the cactus moth Cactoblastis cactorum (Berg) in Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands. Journal of Agricultural of the University of Puerto Rico 55: 130–134.

Hight SD, Carpenter JE, Bloem S, Bloem KA. 2005. Developing a sterile insect release program for Cactoblastis cactorum (Berg) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae): Effective overflooding ratios and release-recapture field studies. Environmental Entomology 34: 850–856.

Heinrich C. 1956. American moths of the subfamily Phycitinae. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 207. 581 pp.

Jezorek HA, Stiling PD, Carpenter JE. 2010. Targets of an invasive species: Oviposition preference and larval performance of Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) on 14 North American opuntioid cacti. Environmental Entomology 39: 1884–1892.

LSU. (July 2009). Cactus Moth. LSU AgCenter Pest Alerts. (22 August 2012).

Marsico TD, Wallace LE, Ervin GN, Brooks CP, McClure JE, Welch ME. 2011. Geographic patterns of genetic diversity from the native range of Cactoblastis cactorum (Berg) support the documented history of invasion and multiple introductions for invasive populations. Biological Invasions 13: 857–868.

Paraiso O, Hight SD, Kairo MTK, Bloem S. 2011. Egg parasitoids attacking Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in north Florida. Florida Entomologist 94: 81–90.

Perez-Sandi M. 2001. Addressing the threat of Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera : Pyralidae), to Opuntia in Mexico. Florida Entomologist 84: 499–502.

Simmonds FJ, Bennett FD. 1966. Biological control of Opuntia spp. by Cactoblastis cactorum in the Leeward Islands (West Indies). Entomophaga 11: 183–189.

Soberon J, Golubov J, Sarukhan J. 2001. The importance of Opuntia in Mexico and routes of invasion and impact of Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera : Pyralidae). Florida Entomologist 84: 486–492.

Starmer WT, Aberdeen VA, Lachance MA. 1987. The yeast community associated with decaying Opuntia stricta (Haworth) in Florida with regard to the moth, Cactoblastis cactorum (Berg). Florida Scientist 51:7–11.

Stiling P, Moon D, Gordon D. 2004. Endangered cactus restoration: Mitigating the non-target effects of a biological control agent (Cactoblastis cactorum) in Florida. Restoration Ecology 12: 605–610.

Vigueras AL, Portillo L. 2001. Uses of Opuntia species and the potential impact of Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera : Pyralidae) in Mexico. Florida Entomologist 84: 493–498.

Zimmermann HG, Moran VC, Hoffmann JH. 2001. The renowned cactus moth, Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae): Its natural history and threat to native Opuntia floras in Mexico and the United States of America. Florida Entomologist 84: 543–551.