The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

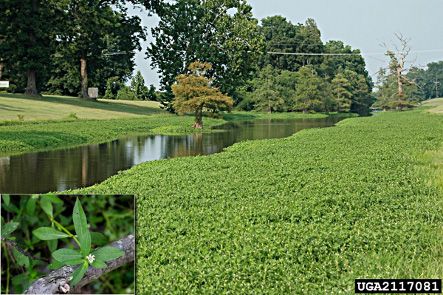

Alligatorweed, Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb. (Amaranthaceae), is an invasive aquatic plant native to South America that began threatening Florida's waterways in the early 1900s. This rooted perennial herb reproduces vegetatively from stem fragments and forms dense floating mats. The floating mats impede navigation, block drains and water intake valves, reduce light penetration, and displace native species. Alligatorweed is a prohibited species in Florida (Lieurance et al 2015).

The alligatorweed flea beetle, Agasicles hygrophila Selman and Vogt, was the first insect ever studied for biological control of an aquatic weed (Center et al., 2002). The introduction of this insect into the United States was approved in 1963, but it was not successfully established on the invasive alligatorweed until 1965. The insect was first released in 1964 in California, and subsequently, in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas.

The first successful release in Florida was made on plants infesting the Ortega River near Jacksonville, FL. These insects were originally obtained from the Ezeiza Lagoon near Buenos Aires, Argentina (Buckingham et al. 1983). Most of the beetles that were later released at subsequent locations were progeny (offspring) from this original population.

Distribution

Agasicles hygrophila is native to southern Brazil and northern Argentina. It also is present in Australia, China, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, and Thailand, where it was introduced as a biological control agent of alligatorweed and in Taiwan where it is thought to have spread from introductions in China (CSIRO 2004, Winston et al. 2014).

In the United States, this leaf beetle is present in the southeastern US, but is less common in northern inland areas where winter temperatures eliminate the emerged portions of the plants and summers are hot and dry.

Description

Eggs

When the eggs are laid, they are uniformly light cream colored but change to a pale orange yellow 24 hours later. On average, the eggs measure 1.25 mm by 0.38 mm and are laid in two parallel rows. Each pair of eggs forms a "V", which creates a chevron-like pattern for the mass. An egg mass contains from 12 to 54 eggs (average = 32).

Larvae

Neonates (newly hatched larvae) lack complete pigmentation; the head, legs and body are pale gray. The legs turn brown in color within a few hours after eclosion (hatching). Older larvae are light gray in color with a brown head and legs. The integument (external covering) of mature larvae is dark gray in color. The instars (larvae between successive molts) range in length from 1.2 to 2.0 mm, 2.2 to 4.0 mm, 4.1 to 6.0 mm, for the first to third instars, respectively. Head capsule widths for the three instars measure 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 mm, respectively.

Credit: Gary Buckingham, USDA-ARS; Bugwood.org

Pupae

The pupae (nonfeeding, transitional stage) are soft-bodied and uniformly pale cream in color.

Adults

Adult alligatorweed flea beetles measure 5 to 7 mm in length and about 2 mm in width. The shiny adults have a black head and thorax; the elytra (hardened forewings) are black with yellow stripes.

Credit: USDA-ARS

Life Cycle and Biology

Adult females begin to lay eggs about six days after emerging from the pupal stage. They deposit their eggs in masses on the undersides of alligatorweed leaves. Oviposition continues for about three weeks during which the female produces, on average, 1,127 eggs during her lifetime, which averages 48 days.

The larvae hatch in four days when the ambient temperature ranges from 20°C to 30°C. Larvae emerge from the eggs by rupturing the chorion (egg covering) along a longitudinal line for a distance of about one-third its length. Neonates prefer to feed on young leaves, and larvae are gregarious at first but later become solitary as they move away from the egg masses. The stadia (developmental periods) are three, two, and three days for the three instars, respectively. Total developmental time for the larval stage is eight days.

After the larvae are mature, they search for a suitable site in which to pupate typically within the hollow stem of alligatorweed, so stem diameter is critical. They normally descend from the tip to the fourth internode (portion of the stem between leaf nodes) but always pupate above the waterline. Larvae chew a circular hole in the internode and enter the hollow stem with the head oriented toward the growing tip. They plug the hole with masticated (chewed) plant tissue and seal off a chamber within the stem. The flea beetle is unable to reproduce on the terrestrial form of alligatorweed because the stems are solid, which prevents pupation.

In the southeastern United States, two population peaks (spring and fall) occur in the southern most parts of the insect's range whereas only one generation (fall) occurs in the more northerly areas. Because the beetles are poorly adapted to freezing temperatures (lack a winter diapause), they starve during the winter months when alligatorweed populations are frozen down to the waterline. The beetlesalso are vulnerable to high temperature; their fecundity (egg production) is reduced at temperatures above 26°C.

Host

The only known host of Agasicles hygrophila is the alligatorweed, Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb. (Amaranthaceae).

Credit: Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

Economic Importance

Alligatorweed flea beetles kill the plant by destroying its stored food and interfering with photosynthesis by removing leaf tissue. Both adults and larvae feed on the leaves of alligatorweed, often defoliating the stems. After the leaves have been consumed, the insects will then chew the epidermis (outer surface) from the stems. Feeding damage by young larvae consists of circular pits < 1 mm in diameter located on the abaxial (lower) surface of the leaf. Larvae do not chew entirely through the leaf but leave the upper surface intact. Later instars consume more leaf tissue, creating larger and more irregular feeding pits, and may feed on either side of the leaf. High flea beetle populations can decimate alligatorweed, reducing it to bare stems in a short time. From a distance, alligatorweed mats under attack appear yellow, progressing to brown until the plants collapse. Once established, this insect can reduce plant populations in about 3 months.

This insect has been an extremely effective biological control agent in coastal regions of the southeastern United States, as can be seen in U.S. Army Corps of Engineer photographs (USACE 2007). Because the beetles cannot survive exposure to winter temperatures, populations of the insects are routinely re-established in the northern inland areas by augmentative releases conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Jacksonville Office (USACE 2008). This is a novel case of a classical biological control agent being used for augmentative biological control of alligatorweed in areas where the beetle is unable to establish permanent populations.

Selected References

Buckingham GR, Boucias D, Theriot RF. 1983. "Reintroduction of the alligator flea beetle (Agasicles hygrophila Selman and Vogt) into the United States from Argentina." Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 21: 101–102.

Buckingham GR. 2002. Alligatorweed. pp. 5-16. In Van Driesche R, Blossey B, Hoddle M, Lyon S, Reardon R (editors). Biological Control of Invasive Plants in the Eastern United States, USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2002-04.

Center TD, Dray Jr FA, Jubinsky GP, Grodowitz MJ. 2002. Insects and Other Arthropods That Feed on Aquatic and Wetland plants. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Technical Bulletin No. 1870.

CSIRO. (2004). Alligatorweed flea beetle, Agasicles hygrophila Selman & Vogt. CSIRO Entomology. http://www.ento.csiro.au/aicn/name_c/a_25.htm (19 August 2009).

Grodowitz MJ, Whitaker, SL. (2005). Agasicles hygrophila - Alligatorweed Flea Beetle. Engineer Research and Development Center. http://el.erdc.usace.army.mil/apis/Biocontrol/BiologicalControlInformation.aspx?BioID=3 (15 May 2014).

Langeland KA, Cherry HM, McCormick CM, Craddock Burks, KA. 2008. Identification and Biology of Nonnative Plants in Florida's Natural Areas, 2nd Edition. University of Florida/IFAS. Gainesville, FL. (8 February 2023).

Masterson J. (December 2007). Agasicles hygrophila, Alligatorweed Flea Beetle. Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce. https://irlspecies.org/taxa/index.php?quicksearchselector=on&quicksearchtaxon=Agasicles+hygrophila&taxon=&formsubmit=Search+Terms (8 February 2023).

Lieurance D, Flory S. Cooper AL, Gordon DR, Fox AM Dusky J, Tyson L. (November 2013). Assessment of Nonnative Plants in Florida's Natural Areas: History, Purpose, and use. SS-AGR-371. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ag376 (November 2015).

USACE (October 2007). Agasicles hygrophila Selman & Vogt - "Alligatorweed Flea Beetle." U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Environmental Laboratory. http://el.erdc.usace.army.mil/pmis/intro.aspx [September 2011].

USACE. (July 2008). Alligatorweed. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Jacksonville. https://www.saj.usace.army.mil/Missions/Environmental/Invasive-Species/Management/ [30 October 2012].

Winston RL, Schwarzländer M, Hinz HL, Day MD, Cock MJW, Julien MH (eds.). 2014. Biological control of weeds: A world catalogue of agents and their target weeds, 5th edition. USDA Forest Service, FHTET, Morgantown, West VA, FHTET-2014-04.