Cucurbit crops (cucumber, squash, cantaloupe, watermelon, chayote, luffa and others) are widely grown in Florida and are very susceptible to damage from various plant-parasitic nematodes. These can severely reduce the vigor and yield of plants, and lead to symptoms like wilting, chlorosis, leaf die-back, plant stunting and fruit malformation. Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) are considered the most important nematode pest in cucurbits. This paper will help cucurbit growers understand what plant-parasitic nematodes can affect their crop and what nematode management strategies are available to them.

Cucurbit Crops in Florida

Many cucurbit crops are grown throughout Florida, the most common being watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), squash and zucchini (Cucurbita pepo) and cantaloupe (Cucumis melo). In addition, several other cucurbit crops are grown, such as pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima and C. moschata), bittermelon (Momordica charantia), chayote (Sechium edule), luffa (Luffa spp.), Chinese cucumber (Trichosanthes kirilowii) and more (Frey et al., 2024).

Main Plant-Parasitic Nematodes in Cucurbits

Plant-parasitic nematodes (PPN) are microscopic roundworms that feed on living plant tissues, mostly the belowground parts of plants like roots and tubers. All PPN have six life stages (egg, four juvenile stages and adult stage) and have a mouth stylet with which they feed by piercing and sucking on plant cells (mostly roots). Life cycle duration varies by species and with temperature and typically will range from 2–6 weeks. Different genera and species of nematodes can be important to cucurbit production in Florida. The most important ones are root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.), followed by sting nematodes (Belonolaimus longicaudatus), reniform nematodes (Rotylenchulus reniformis), stubby root nematodes (Trichodoridae) and lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus spp.).

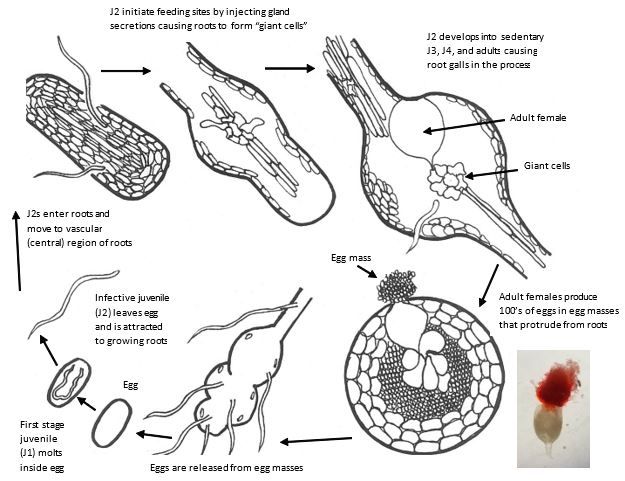

Root-knot nematodes (RKN, Meloidogyne spp.) can cause significant yield losses in cucurbit crops in Florida. The warm climate and sandy soil conditions are very conducive for these nematodes and many different species can be found in Florida. The main species of importance to cucurbits are Meloidogyne incognita, M. enterolobii, M. javanica, M. arenaria, M. floridensis and M. hapla. RKN are endoparasitic nematodes, which means that they spend most of their life inside the root (Figure 1). The infective stage in the soil is the J2 (second-stage juvenile, about 0.5 mm long, Figure 2) that emerges from the egg and will search for suitable roots. Once they enter the root, specialized cells (giant cells) are formed with the sole purpose of feeding the developing nematode. Under favorable conditions, after about 2–4 weeks, females lay their eggs, which are secreted in egg masses on the root surface. RKN infection is usually accompanied by the formation of root galls, and when infestation is heavy roots can appear severely swollen.

Credit: H. Regier, adapted from G. Abawi and V. Brewster; Insert bottom right: J. Coburn

Credit: H. Bui, UF/IFAS

Sting nematode (Belonolaimus longicaudatus) is the second most important nematode on cucurbit crops. This nematode is a large (1–2 mm) ectoparasite, and spends its entire life in the soil, feeding on newly emerging roots. This stops the new roots from elongating, resulting in a short, stubby looking and ineffective root system. Both root-knot and sting nematodes have a high preference for soils with high sand content (>80% sand) and are common in sandy regions along the Gulf of America (formerly Gulf of Mexico) and Atlantic coasts.

Symptoms, Damage and Diagnosis

Plant-parasitic nematodes (PPN) reduce the vigor and yield of plants. The typical aboveground symptoms of PPN damage are stunting, wilting, leaf die-back, leaf discoloration and fruit malformation (Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6). All these symptoms can be (and often are) misidentified with other causes such as nutrient or water deficiency, plugged drip irrigation lines, or diseases related to bacteria or fungi.

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

The level of PPN damage is related to nematode population density, crop susceptibility, and prevailing environmental conditions. For example, under heavy nematode infestation, crop seedlings or transplants may fail to develop, maintain a stunted condition, or die, causing poor or patchy stand development (Figures 7, 8, and 9). Under less severe infestation levels, symptom expression may be delayed until later in the crop season after several nematode reproductive cycles have been completed on the crop. In this case, aboveground symptoms will not always be readily apparent early within crop development, but with time and reduction in root system size and function, symptoms become more pronounced and diagnostic (Figures 3, 4, and 5).

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

Whenever aboveground symptoms are observed, roots should be checked to verify if nematodes are the cause. Root symptoms induced by root-knot nematodes on cucurbit crops can usually easily be seen as swollen areas (galls) on the roots of infected plants (Figures 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8). Symptoms of root galling can in most cases provide positive diagnostic confirmation of nematode presence, infection severity, and potential for crop damage. While the presence of galls or knots on roots is usually a clear sign of root-knot nematode infection, nematode galls can be overlooked when small (early in the season, low nematode pressure) and when roots are covered with soil. Gall size may range from small to large depending on the interaction between each cucurbit crop and RKN species, as well as the population density and time of infection. Northern RKN (Meloidogyne hapla) usually induces small galls while tropical species (most other RKN species in Florida) induce larger galls. That said, significant differences in virulence and damage may occur among geographical populations of different RKN species. Also, when cucurbits are direct seeded in heavily infested soil, M. hapla can also cause severe galling (Figure 8). M. hapla is only found in fields where strawberries are grown (Figures 6 and 8). This nematode has likely been introduced into these fields with transplants from northern nurseries (Desaeger, 2018). In this case, the cucurbits are not the main crop but are grown as a double or relay-crop in early spring following the main strawberry crop. Strawberry is a good host for M. hapla and especially when cooler soil temperatures, which favor the nematode, occur in late winter-early spring; the population can increase rapidly and reduce crop establishment and early growth of cucurbits (Figures 6 and 8). In all other fields, the RKN species are mostly M. incognita, M. javanica or M. enterolobii, all of them capable of causing significant root damage and crop loss.

Root damage from other nematodes is less conspicuous. Sting nematodes cause infected plants to form a tight mat of short roots, often with root tips having a swollen appearance. New root initials generally are killed by heavy infestations of the sting nematode, a symptom reminiscent of fertilizer salt burn.

Credit: J. Desaeger, UF/IFAS

Stubby root nematode infection can cause roots to have a bearded appearance and can look like sting nematode damage. Lesion nematodes may cause necrotic spots and dark lesions on the roots, similar to many fungal root rot pathogens.

As a general rule, whenever plants grow poorly, the first course of action should always be to look at the roots. Abnormal looking roots are often a telltale sign of nematode damage (or another soilborne pathogen). However, for most nematodes, other than root-knot nematodes, diagnostic root symptoms may not be easily observed, and proper diagnosis will need to be done at a nematology lab. Sampling and diagnosis will require collecting soil and root samples from infected plants or hotspots, which typically occur as irregular patches of poorly growing plants. It is always advisable to send both soil and roots for diagnosis. Check with your local UF/IFAS Extension office for assistance with nematode sample analysis. Samples can be sent for verification to the nematology lab at the UF/IFAS Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (UF/IFAS GREC) in Balm, FL, or to the UF/IFAS Nematology Assay Lab in Gainesville, FL.

Nematode Management

Field Sanitation and Monitoring

Nematodes are often introduced into new fields through infected plant material (transplants) and equipment. Therefore, sanitation should always be the first resource against PPN. When transplants are used, these should be healthy and nematode-free. Farm equipment should be cleaned when moving between fields, especially when fields are known to have (or have had) nematode problems. Nematodes are aquatic organisms and movement within a field is mostly with water. Therefore, limiting run-off water within a field is advisable.

After harvesting, the crop should be killed or rogued to stop any further nematode reproduction. Whenever feasible, removing nematode-infested (galled) roots from the field immediately after harvest is a good practice as this will reduce the nematode inoculum in the field. Also, as many weeds are known to be good hosts for PPN, good weed control during and after the crop will help with reducing nematode build-up.

Field monitoring by regularly checking roots for nematode symptoms and having soil analyzed for nematodes will allow identification of nematode hotspots in the field and adoption of more targeted management. Nematode hotspots may be associated with differences in field management but usually appear to be random.

Cultivar and Transplant Selection

There are currently no RKN-resistant commercial cucurbit varieties available. All cucurbit crops should be considered as good hosts to RKN. However, there are noticeable differences in susceptibility among different species. For instance, cucumber and watermelon are generally more susceptible and suffer greater damage than squash and zucchini (Bui and Desaeger, 2021). Also, using transplants that already have a root system, rather than direct seeding, will help with crop establishment as these plants will be able to better tolerate early nematode feeding.

Crop Rotation/Cover Crop

Crop rotation with non- or poor nematode host crops is one of the main pillars of nematode management, but is difficult when dealing with nematodes, like root-knot and sting, that can attack many different crops. Some options of non/poor host rotation crops are root-knot-resistant cultivars. Such cultivars have been available for tomatoes for many years and protect against three species of RKN, M. incognita, M. javanica and M. arenaria (Regmi and Desaeger, 2019). They will not protect against any of the other RKN species, most notably M. enterolobii and M. hapla. More recently, RKN-resistant pepper cultivars (Charleston Belle, Carolina Wonder and Carolina Cayenne) have become available that protect against the same three species. In addition, regular pepper cultivars can be good rotation crops, if the RKN species is M. javanica, as most populations of this species do not infect pepper. Several crops from the Brassicaceae family, like cabbages and other crops, could also be good rotation crops as they are generally poorer hosts and suffer less yield loss than cucurbits.

Alternatively, if rotation crops are not an option, cover crops can be planted in between cucurbit crops. In Florida, sunn hemp and sorghum-sudangrass are poor hosts to RKN, and good options to help manage RKN. In addition, the biomass from both cover crops produces nematicidal compounds when incorporated in the soil (Bui and Desaeger, 2021).

When using cover crops to help manage nematodes, one must keep in mind that almost always a mixed community of plant-parasitic nematodes is present in a field, often with different plant host preferences. For instance, sorghum-sudangrass, is a poor host for most RKN species, but it is a good host for many other nematodes, including sting and stubby root nematodes. Also, the cover crop cultivar and RKN species can make a difference. In the case of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), which is another common cover crop in Florida, this crop can behave very differently depending on cultivar and RKN species. Cowpeas are generally very good hosts for RKN species like M. arenaria, M. enterolobii and M. javanica, but not so much for M. incognita (Bui and Desaeger, 2021; Wang et al., 2021).

Nematicides

Nematicides can be separated into fumigants and non-fumigant products. Soil fumigants are 1,3-Dichloropropene (1,3-D, Telone), chloropicrin (Pic) or MITC/AITC-based products (KPam, Vapam, Dominus). Non-fumigant nematicides registered for cucurbit crops are oxamyl (Vydate®), ethoprophos (Mocap®, only for cucumber), fluensulfone, (Nimitz®), fluopyram (Velum®) and fluazaindolizine (Salibro®).

Biological nematicides include fungal (Purpureocillium lilacinum), bacterial (Burkholderia rinojensis) and plant-based (azadirachtin, thyme oil, and others) products.

For more information and application rates on nematicides check the UF/IFAS Vegetable Production Handbook (Frey et al., 2024; Peres et al., 2024), and other EDIS publications, ENY033 (“Non-Fumigant Nematicides Registered for Vegetable Crop Use”), and ENY065 (“Fumigant and Non-Fumigant Nematicides Labeled for Agronomic Crops in Florida”).

All chemical nematicides require a pesticide applicator license and in the case of fumigants a separate fumigant applicator license (check with your local UF/IFAS extension office).

Cultural and Other Practices

Organic amendments: frequent applications of organic amendments (animal and green manures, compost, etc.) will increase soil organic matter and microbial activity while stimulating natural enemies that help to reduce the damage caused by PPN. Organic amendments also will increase the water- and nutrient-holding capacity of the soil, especially in sandy soils. Because nematodes will cause more damage to water-stressed plants, this can lessen the effects of nematode injury without reducing levels of damaging nematodes.

Fallowing is the practice of leaving the soil bare; it tends to be more effective when the soil is kept moist, which induces nematode eggs to hatch and emerging nematodes to starve because there is no food source. As many weeds are good hosts for nematodes, it is important to control weeds on which nematodes can survive during the fallow period. Fallowing is also more effective when combined with frequent tillage which can reduce nematode populations further by bringing them to the surface and exposing them to the sun.

Solarization by covering and heating up the soil with clear plastic for four to six weeks is another method that can be used to reduce nematodes in a field. However, as nematodes move downwards, nematode control tends to be limited to the upper soil layers. Another method of using heat to control nematodes is through the application of steam using specialized steam applicators (Fennimore and Goodhue, 2016).

Flooding: temporary and seasonal flooding of fields is practiced in some areas in south Florida and can provide good nematode control if flooding conditions can remain for at least 1-2 months. A variant of this method is anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD), which includes applying a labile carbon source (molasses, rice bran, etc.) in combination with a high amount of water (Butler et al., 2012).

Table 1. Different nematode management options in cucurbit crops.

References

Baker KF and Roistacher CN (1957). Heat treatment of soil. Principles of heat treatment of soil. Equipment for heat treatment of soil. Calif. Agr. Exp. Sta. Manual 23:123–196, 290–293, 298–304.

Bui HX and Desaeger JA. (2021). Host suitability of summer cover crops to Meloidogyne arenaria, M. enterolobii, M. incognita and M. javanica. Nematology, 24(2), 171–179.

Butler DM, Kokalis-Burelle N, Muramoto J, Shennan C, McCollum T, and Rosskopf EN. (2012). Impact of anaerobic soil disinfestations combined with soil solarization on plant-parasitic nematodes and introduced inoculum of soilborne plant pathogens in raised-bed vegetable production. Crop Protection 39:33–40.

Desaeger J (2018). Meloidogyne hapla, the Northern Root-knot Nematode, in Florida Strawberries and Vegetables. ENY070. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2018, 5 pages. [Accessed 4/19/2019] https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1224

Dittmar PJ, Dufault NS, Desaeger J, Qureshi J, Boyd N, and Paret M (2024). Chapter 4. Integrated Pest Management in Vegetable Production Handbook for Florida 2024-2025. CV298. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, p. 31–50. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CV298

Fennimore SA and Goodhue RE (2016). Soil disinfestation with steam: A review of economics, engineering, and soil pest control in California strawberry. International Journal of Fruit Science, 16(sup1): 71–83.

Frey C, Boyd NS, Paret M, Wang Q, Desaeger J, Qureshi J, Meszaros A, Dufault N, Roberts P and Martini X (2024). Chapter 7. Cucurbit Production in Vegetable Production Handbook for Florida 2024-2025. HS725. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, p. 93–148. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CV123

Peres N, Vallad G, Desaeger J and Lahiri S (2024). Chapter 19. Biopesticides and Alternative Disease and Pest Management Products in Vegetable Production Handbook for Florida 2024-2025. CV295. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, p. 653–669. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CV295

Regmi H G and Desaeger J (2019). Nematode Resistance: A Useful Tool for Root-knot Nematode (RKN) Management in Tomato. ENY072. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2019, 5 pages. [Accessed 1/20/2025] https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1250

Wang KH, McSorley R, Grabau Z and Rios E (2021). Management of Nematodes with Cowpea Cover Crops. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2021. [Accessed 1/20/2025] https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN516