Introduction

Biofuel can be described as "any fuel made from organic materials or their processing and conversion derivatives" (USEPA 2018). This publication serves as an introduction to biofuels for Extension educators and anyone interested in learning basic terminology, concepts, and impacts of biofuels as a replacement for fossil fuels.

Simply, biofuels are combustible fuels derived from recently produced biomass, as opposed to ancient biomass, which is the source of petroleum products. The term biofuel usually refers to liquid fuels used as replacements for or additives to petroleum-based liquid fuel. In the literature, the term bioenergy has been used interchangeably with biofuel, though it is more commonly used to describe any energy source based on recently produced biomass—everything from food, fiber, wood, grasses, crop residues, and even industrial and municipal wastes. Nevertheless, biofuel can be categorized into two broad groups—bioethanol (more commonly referred to as ethanol) and biodiesel. The basic difference between the two is that ethanol is an alcohol, the same as in beer and wine (although biofuel-ethanol is undrinkable), and biodiesel is an oil. World-leading ethanol- and biodiesel-producing countries are listed in Table 1 (REN21 2018).

Classification

Based on the type of feedstock used to produce either ethanol or biodiesel, biofuels are grouped into three categories—first generation, second generation, and third generation (Lee and Lavoie 2013). Additionally, "Advanced Biofuels" is a term generally used to describe comparatively new biofuel production technologies that use waste such as garbage, spent cooking oil, and animal fats as feedstock.

- First-generation ethanol/biodiesel is produced directly from biomass that is generally a food source. Ethanol is produced by fermenting sugar or starch in food-crop sources that are biochemically categorized as carbohydrates. The major source of sugar is sugarcane, while corn is the major source of starch (USEPA 2010). Besides cane and corn, first-generation ethanol is produced from but not limited to other less popular sources like wheat, barley, and sugar beet (Table 2). The sources of first-generation biodiesel are soybean, rapeseed (canola), sunflower, and palm, which are edible oil crops (USEPA 2010).

- Second-generation ethanol/biodiesel is produced from non-edible biomass sources. The sources of second-generation ethanol include dedicated biofuel grasses, crop residues, and wood chips, which are biochemically categorized as lignocellulosic materials (Table 2). Second-generation biodiesel is produced from non-edible oils, and most comes from jatropha (Bhuiya et al. 2014). Other minor sources include jojoba, karanja, moringa, castor, soapnut, and cotton seed oil (Atabani et al. 2013).

- Third-generation ethanol/biodiesel is commonly produced from algae, a single-cell organism. Generally, algae are categorized based on their habitat, such as freshwater algae, marine algae, or wastewater algae. Based on its characteristics, a specific alga is chosen for either ethanol or biodiesel production (Wilkie et al. 2011).

Production

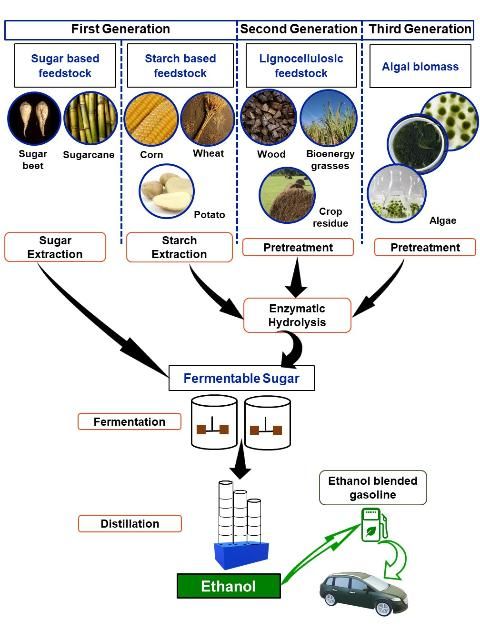

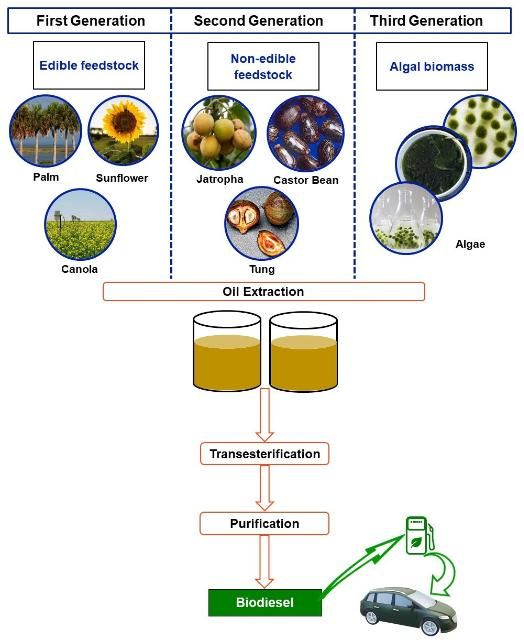

Ethanol and biodiesel are produced through different biochemical/chemical pathways. Fermentation and transesterification are the major pathways for ethanol and biodiesel production, respectively (Lee and Lavoie 2013). Thus, ethanol is produced by fermenting any biomass high in carbohydrates (sugar/starch/cellulose) through a process similar to beer brewing (Figure 1). In first-generation ethanol production, starch is enzymatically hydrolyzed to fermentable sugar before going through the fermentation process. In second- and third-generation ethanol production, cellulose is extracted from the lignocellulosic structure by different pretreatments and then enzymatically hydrolyzed to fermentable sugar. Compared to ethanol production, biodiesel production is theoretically more straightforward. Basically, all three types of biodiesel feedstocks are first extracted to get oil, and then the oil is converted to biodiesel through a process known as transesterification (Figure 2).

Potential Benefit

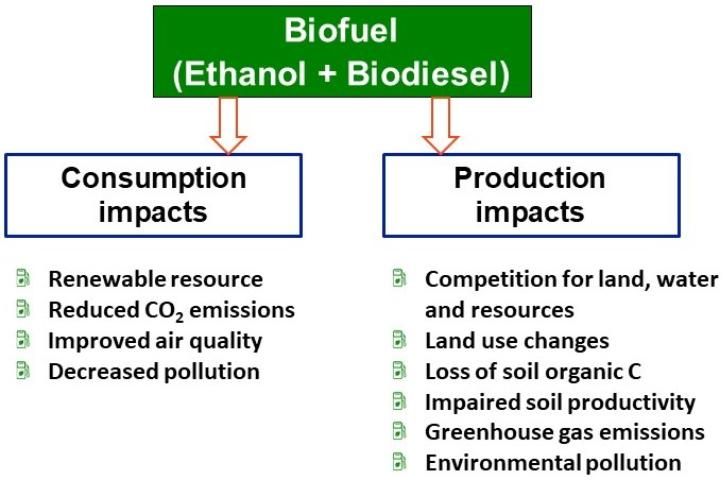

Biofuel production has a number of potential benefits for replacing finite fossil fuels that are being depleted day by day (Figure 3). Theoretically, biofuel is a renewable energy source compared to nonrenewable fossil fuel (Table 3). In its first triennial report to congress, USEPA (2011) had predicted that biofuel from corn or soybean could have lower lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than gasoline. Specific economic modeling studies also suggested lower lifecycle GHG emissions from biofuel production and use than from conventional petroleum-based fuel (Huang et al. 2013). Biofuel produced from non-edible sources (i.e., second- and third-generation biofuel) has added advantages. Most of the second- and third-generation biofuels are either produced on marginal or extra land, or are the co-products of agricultural production systems with no added cost of production and with little or no alternate uses. Biofuels also reduce environmental pollution by decreasing CO2 emissions and improving air quality (USEPA 2010). However, biofuel production and consumption by themselves still have impacts on conventional pollutant emissions (like CO2). Biofuel has advantages over petroleum-based fuel provided that biofuel production and consumption do not increase environmental pollution or augment demand for resources like arable land, water, fertilizer, and pesticides.

Considerations

Though biofuel provides an attractive alternative to current petroleum-based transportation fuel, its production impacts cannot be overlooked (Figure 3). The major challenges for long-term sustainability of biofuel production are mainly twofold: economic and environmental. Most biofuel feedstocks are agricultural products, which is a point of major concern. The key economic issue is that if food crops are used for biofuel production (which is the case for first-generation ethanol and biodiesel), then there will be a shortage of food grains in the market, leading to higher dietary costs (Hill et al. 2006). To address this concern, second-generation biofuel production, which relies on either the biomass residues or non-edible agricultural products, has been developed.

However, second-generation biofuel production is also subject to environmental and economic concerns. Removing residues from the field for second-generation biofuel production aggravates environmental problems due to reduction of soil organic carbon that otherwise would accumulate in soil when crop residues are retained (Lal 2005). Loss of soil organic carbon leads to a vicious cycle of increased soil erosion, increased GHG emissions, lower soil productivity, higher mineral fertilizer input, increased cost of production, and impaired water quality due to surface runoff (National Research Council 2011). Growing dedicated crop biomass only for first- or second-generation biofuel production either competes with agricultural and pasture land or leads to deforestation with increased GHG emissions (Fargione et al. 2008, Melillo et al. 2009).

Production of crop biomass for biofuel on marginal lands also increases the use of fertilizer, water, and pesticides, which impacts the environment negatively (Searchinger et al. 2008). Despite these concerns, the future of biofuel production is not entirely bleak. The solution could involve producing biofuel in substantial quantities from feedstocks that have low environmental impact and little or no competition with food production. The application of biofuel industry by-products back to soil could be a complementary strategy to increase soil quality (Bera et al. 2019) and possibly mitigate the potential impacts of biofuels.

Third-generation biofuels from cultured algal biomass or advanced biofuels from domestic and industrial wastes have certain advantages over biofuels from agricultural feedstocks. Nevertheless, production of biofuels from algae also has the potential for significant resource use and negative environmental impacts, though this is true for all forms of energy production (Georgianna and Mayfield 2012). However, biofuel production from algae that are highly productive and less resource intensive is considered an economically viable biofuel production pathway at present (National Research Council 2012). Ultimately, any new kind of biofuel production technology needs to be environmentally sustainable and economically profitable.

References

Atabani, A. E., A. S. Silitonga, I. A. Badruddin, T. M. I. Mahlia, H. H. Masjuki, and S. Mekhilef. 2012. "A Comprehensive Review on Biodiesel as an Alternative Energy Resource and Its Characteristics." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16:2070–2093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.01.003

Atabani, A. E., A. S. Silitonga, H. C. Ong, T. M. I. Mahlia, H. H. Masjuki, I. A. Badruddin, and H. Fayaz. 2013. "Non-edible Vegetable Oils: A Critical Evaluation of Oil Extraction, Fatty Acid Compositions, Biodiesel Production, Characteristics, Engine Performance and Emissions Production." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 18:211–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.10.013

Bera, T., L. Vardanyan, K. S. Inglett, K. R. Reddy, G. A. O'Connor, J. E. Erickson, and A. C. Wilkie. 2019. "Influence of Select Bioenergy By-products on Soil Carbon and Microbial Activity: A Laboratory Study." Science of the Total Environment 653:1354–1363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.237

Bhuiya, M. M. K., M. G. Rasul, M. M. K. Khan, N. Ashwath, A. K. Azad, and M. A. Hazrat. 2014. "Second Generation Biodiesel: Potential Alternative to-Edible Oil-Derived Biodiesel." Energy Procedia 61:1969–1972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.12.054

Fargione, J., J. Hill, D. Tilman, S. Polasky, and P. Hawthorne. 2008. "Land Clearing and the Biofuel Carbon Debt." Science 319:1235–1238. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152747

Georgianna, D. R., and S. P. Mayfield. 2012. "Exploiting Diversity and Synthetic Biology for the Production of Algal Biofuels." Nature 448:329–335. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11479

Hill, J., E. Nelson, D. Tilman, S. Polasky, and D. Tiffany. 2006. "Environmental, Economic, and Energetic Costs and Benefits of Biodiesel and Ethanol Biofuels." PNAS 103:11206–11210. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0604600103

Huang, H., M. Khanna, H. Onal, and X. Chen. 2013. "Stacking Low Carbon Policies on the Renewable Fuels Standard: Economic and Greenhouse Gas Implications." Energy Policy 56:5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.06.002

Lal, R. 2005. "World Crop Residues Production and Implications of Its Use as a Biofuel." Environment International 31:575–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2004.09.005

Lee, R. A., and J.-M. Lavoie. 2013. "From First- to Third-Generation Biofuels: Challenges of Producing a Commodity from a Biomass of Increasing Complexity." Animal Frontiers 3 (2): 6–11. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2013-0010

Melillo, J. M., J. M. Reilly, D. W. Kicklighter, A. C. Gurgel, T. W. Cronin, S. Paltsev, B. S. Felzer, X. Wang, A. P. Sokolov, and C. A. Schlosser. 2009. "Indirect Emissions from Biofuels: How Important?" Science 326:1397–1399. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180251

National Research Council. 2011. Renewable Fuel Standard: Potential Economic and Environmental Effects of U.S. Biofuel Policy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13105

National Research Council. 2012. Sustainable Development of Algal Biofuels in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13437.

Rajagopal, D., and D. Zilberman. 2007. "Review of Environmental, Economic and Policy Aspects of Biofuels." World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4341. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1012473

REN21. 2018. Renewables 2018 Global Status Report. Paris: Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21) Secretariat. http://www.ren21.net/gsr-2018/

Searchinger, T., R. Heimlich, R. A. Houghton, F. Dong, A. Elobeid, J. Fabiosa, S. Tokgoz, D. Hayes, and T.-H. Yu. 2008. "Use of U.S. Croplands for Biofuels Increases Greenhouse Gases through Emissions from Land-Use Change." Science 319:1238–1240. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1151861

USDOE. 2014. "Alternative Fuels Data Center – Fuel Properties Comparison." Alternative Fuels Data Center, U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, DC. https://afdc.energy.gov/fuels/fuel_comparison_chart.pdf

USEPA. 2010. "Biodiesel - Technical Highlights (EPA-420-F-10-009)." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P1006V0I.pdf

USEPA. 2011. "Biofuels and the Environment: First Triennial Report to Congress. EPA/600/R-10/183F." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/biofuels/recordisplay.cfm?deid=235881

USEPA. 2018. "Economics of Biofuels." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. https://www.epa.gov/environmental-economics/economics-biofuels

Wilkie, A. C., S. J. Edmundson, and J. G. Duncan. 2011. "Indigenous Algae for Local Bioresource Production: Phycoprospecting." Energy for Sustainable Development 15 (4): 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2011.07.010