This publication focuses on the importance of potassium nutrition for potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) production. This publication aims to detail the relevance of potassium (K) for tuber production, crop demand for this nutrient, recent market trends, and additional information on K management for potato production in Florida. The target audience includes potato growers, Extension agents, crop consultants, representatives of the fertilizer industry, state and local agencies, students, instructors, researchers, and interested Florida citizens.

Why Potassium

After nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), the nutrient that is considered to be of the utmost significance for plant growth is potassium (K). Potassium improves the overall quality of plants as well as their resistance to the effects of both biotic and abiotic stress. China, Russia, Canada, Belarus, and Germany are the only countries in the world with large potassium producers. This is because potassium resources are in short supply. As a direct result of this, the price of K fluctuates in reaction to the shifting political climate (Pistilli 2022).

Why Potato

One of the most difficult aspects of food production is ensuring that there will be enough food for people in the here and now as well as in the future while protecting our natural resources such as water, land, and the environment. This is one of the most important aspects of the agricultural production system. The global food system will need modifications to achieve sustainability in food production and dietary requirements. These enhancements might make it easier for farmers to make a livelihood and provide people with food that is high in nutrients (Foley et al. 2011). Potatoes provide a significant section of the world's population with their primary source of energy and possess a high production capacity that may be of economic benefit (Swaminathan 2001; Naik 2005). Potatoes were referred to as "the hidden treasure" by the United Nations in 2008. As an essential food crop on a global scale, potatoes need to be a bigger part of crop production, and the crop's quality needs to be preserved. Potatoes are grown in nearly every state in the United States. Florida may not be as well-known for potato production as other states, but it is still the second-highest producer of spring potatoes in the southeastern United States. This suggests that there is a demand for potatoes in this region and that there is potential for further growth in potato production in Florida. Planting potatoes in soils that do not drain well, do not retain much water, and/or do not retain nutrients typically results in poor plant stand and, thus, decreased output potential (Beukema and Zagg 1990). According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), the Agricultural Statistics Board, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the average per acre production of potatoes is 459 cwt, whereas Florida’s per acre production is 300 cwt (USDA-NASS 2024a, 2024b). This disparity in Florida may result from poor soil conditions, obsolete nutrition recommendations, or high temperatures. Utilizing optimal levels of N and K in potato cultivation increases yields (Saravia et al. 2016). Low potato yields may suggest a decline in dry matter production due to poor soil conditions or fertilizer management. Table 1 displays the various K recommendations for the leading potato-growing states in the United States that have recently been modified or re-evaluated due to changes in soil conditions, agricultural methods, and new varieties.

Table 1. Potassium recommendations in major potato-producing US states.

Potato is a crop that requires a great deal of the primary nutrients N, P, and K. In addition to water and sunshine, plants require these additional nutrients to develop and become robust. Considering their importance in the development of plant cells and tissues, macronutrients are in higher demand than micronutrients. If plants do not receive adequate N, P, and K, they may not grow properly, may shed their leaves rapidly, and may produce fewer tubers (Rosen et al. 2015; Hopkins et al. 2020; Uchida 2000). Due to their fibrous, up to 24-inch-deep roots, potatoes are extremely susceptible to nutritional stress (Zaeen et al. 2020). This makes it difficult for potatoes to access deeper levels of nutrients and water (Joshi et al. 2016). Therefore, fertilizers are required to obtain their maximum production potential.

Nutritional Needs of Potato

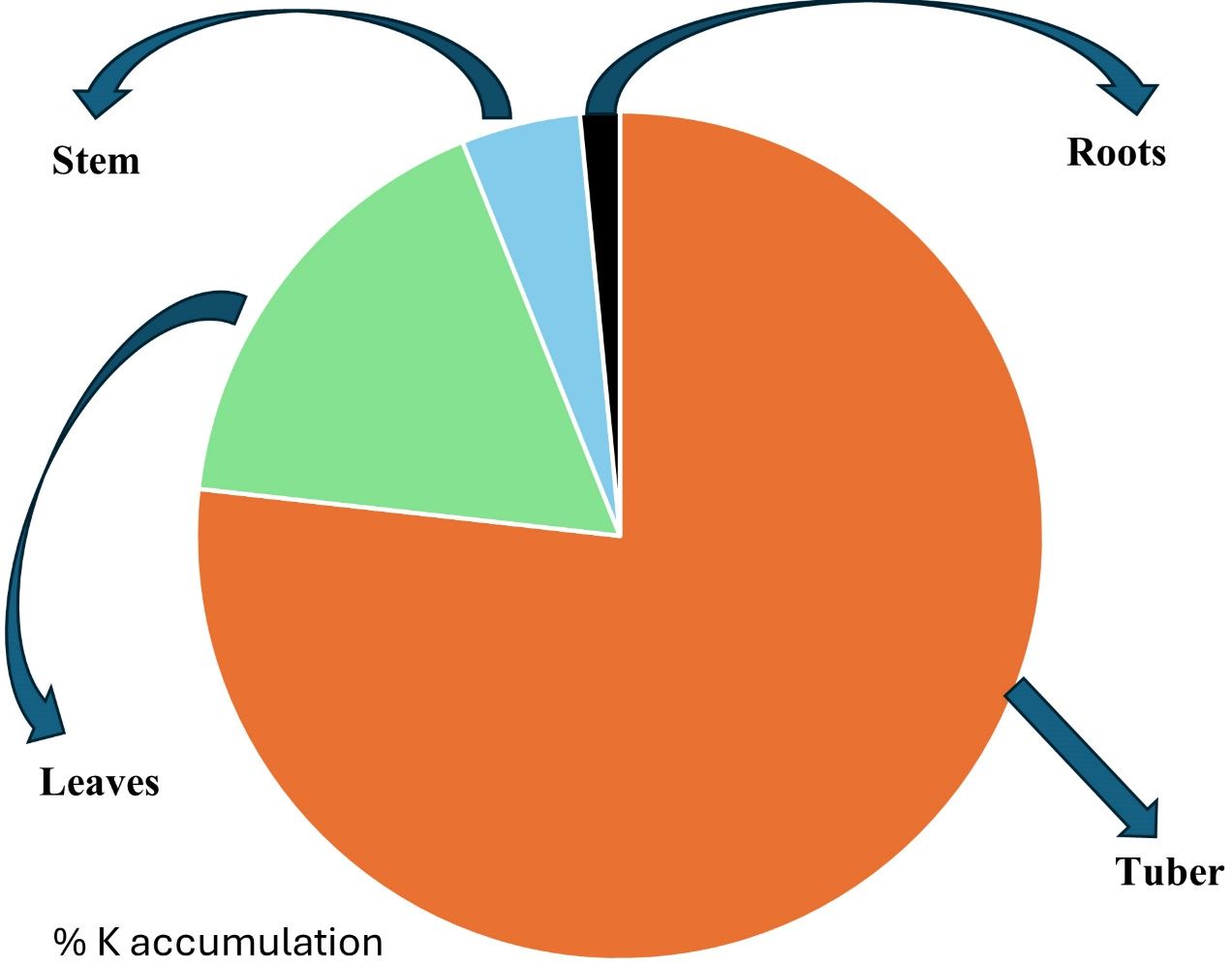

Potassium is vital to plant health and is taken up in large amounts by potatoes (Zotarelli et al. 2021; Koch et al. 2020). Nitrogen is a transporter for the regulation of cell turgor and the formation of starch. Potassium carries sugar from the leaves to the tubers, which is essential for producing abundant crops. Specifically, K nutrition influences potato tuber development, whereas specific gravity influences fry color and storage quality by protecting against after-cooking darkening and black spot bruising. Potassium is required to create high-quality potatoes because it assists in synthesizing photosynthates and their delivery to the tubers. The amount of K in dry matter fluctuates over time and across plant parts, such as leaves and stems. About 78% of the total K content is stored in the tubers at harvest (Figure 1). The bulk of K uptake happens 30 to 60 days after planting if the climate is warm and 65 to 75 days if the temperature is cool.

Credit: Adapted from Sharma and Sud (2001)

K Removal by Potato Crop

In addition to requiring a considerable amount of N and K for growth, potatoes deplete soil nutrients during crop removal and runoff/leaching, necessitating their replacement. Potatoes require N and K at each development stage: while they are still green, when they begin to produce tubers, and when they are becoming larger. Approximately 310 cwt/acre of potato crop may remove more than 100 pounds of nitrogen and 178 pounds of potassium per acre (Otieno and Mageto 2021). Several studies (Table 2) demonstrate that potatoes remove variable amounts of K from different soil types. Moreover, a potato crop has specific nutritional needs at various stages of growth (Fernandes et al. 2015).

Table 2. Potassium removal by potato tubers in different textured soils.

Role of K in Potato Production

The starch concentration of potatoes influences their quality (Das et al. 2021; Moyano et al. 2007; Ludwig 1985). Potassium nutrition increases the specific gravity and, thus, the dry matter accumulation in tubers (Šimková et al. 2013; Nelson et al. 1984). Therefore, potatoes' total dry matter content measures their quality and determines their yields. Potassium is essential for sugar translocation in the leaf, necessitating a sufficient K supply in potatoes. During photosynthesis, sugars are created by leaves. The tubers transform these sugars into starch (Chung et al. 2014). Sugar translocation is a significant factor in determining the yield and quality of potatoes. As K makes it easier for plants to manufacture photosynthates, it is the only nutrient necessary for good potato development.

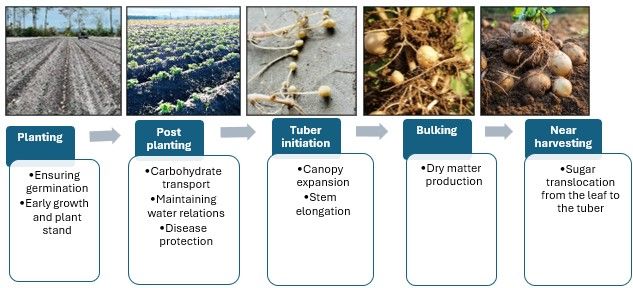

Since potassium is an osmotically active ion, its buildup in plant tissues increases cell turgor by forcing water into the cells (Davenport and Bentley 2001). If potatoes are provided with optimum K, they are better able to survive drought stress (Marton 2001). Potassium is essential for sustaining cell turgor and for the bulk of canopy and stem growth in plants (Schippers 1968). This maximizes the growth rate in the important phases of crops over the whole growing season, which is essential for crops like potatoes. Figure 2 depicts the relevance of K at various stages of potato growth.

Credit: Simranpreet K. Sidhu, UF/IFAS

K Deficiency in Potato

Plants deficient in K frequently become stunted and exhibit other symptoms of deficiency (Thompson and Zwieniecki 2005) (Figure 3). When the symptoms become apparent, yield loss will probably occur, and it is doubtful that K application will be able to recover it at this time. As it is a mobile element in plants, the first indication of a K deficit is burned or brown leaf margins (Figure 4), particularly on older leaves (Torabian et al. 2021). In the worst circumstances, leaves die prematurely, and development is stunted. This has a significant impact on yield and quality.

Credit: Simranpreet K. Sidhu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Simranpreet K. Sidhu, UF/IFAS

Potential K Sources in Florida

Potassium must be accessible to plants at all growth stages since plants cannot utilize the K already present in soil (Olaitan and Lombin 1984). Therefore, the crop must find another source of fertilizer. Depending on the kind of soil, 90%–98% of the total K in soil cannot be extracted (Brady and Weil 2002). Potassium may be derived from three distinct fractions, although plants cannot always utilize them. The first is water-soluble K, which is dissolved in soil solution at a concentration of only 0.1%–0.2%. The second is exchangeable K, which consists of 1%–2% and is adsorbed or released from sites on clay particles and organic materials. The third is slowly accessible K, which is encased in clay particle layers and accounts for 1%–2% (Brady and Weil 2002). Feldspars and micas comprise 60% of the earth's crust as clay minerals. These minerals contain high concentrations of K that can only be attained over time (Sparks 2000). Plants cannot absorb the K in these minerals because they are trapped within the crystalline structures and densely packed between their layers (Schulze 2005). However, when time and weather erode these minerals, the K ions they contain are liberated. This method is excessively time-consuming and cannot provide sufficient K to plants for optimal production.

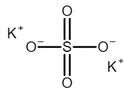

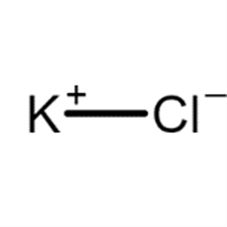

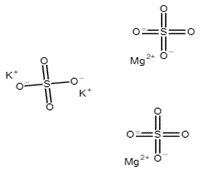

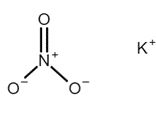

Potatoes may obtain all of the K they require from conventional fertilizers. Different K fertilizers are produced by excavating and purifying salt deposits to remove contaminants (Ciceri et al. 2019). As demonstrated in Table 3, the most significant variation between various K fertilizers is their anionic content and salt index. The fertilizer salt index measures the amount of salt added to the soil solution by fertilizers (Mortvedt 2001). The growth of plants and the type of fruit they produce depend on the salts' chemistry and how they interact with the soil. High salt index fertilizers can be harmful to plants since their roots cannot absorb as many nutrients (Laboski 2008). The K fertilizer with the least amount of salt is potash sulfate. Sulfur is highly effective, dissolves easily in soil solutions, and may be rapidly absorbed, which enables plants to produce a large amount of dry matter (Panique et al. 1997). However, similar to nitrates, sulfates tend to be washed away by runoff water. Therefore, this fertilizer should only be applied when there is less rainfall. When potatoes are at the bulking stage, potassium nitrate can be applied by fertigation or as a side dressing (Haddad et al. 2016). This fertilizer is ideal for high-value crops that require K and N forms that dissolve easily. Most people dislike the muriate of potash because it contains too much chloride, which gives potato tubers an unpleasant flavor (Murphy and Goven 1966; Panique et al. 1997).

Table 3. Different K fertilizers and their salt index.

References

Beukema, H. P., and D. E. van der Zaag. 1990. Introduction to Potato Production (No. 633.491 B4). Pudoc.

Brady, N. C., and R. R. Weil. 2002. The Nature and Properties of Soils. 13th ed. Pearson.

Chung, H., X. Li, D. Kalinga, S. Lim, R. Yada, and Q. Liu. 2014. “Physicochemical Properties of Dry Matter and Isolated Starch from Potatoes Grown in Different Locations in Canada.” Food Research International 57: 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2014.01.034

Ciceri, D., T. C. Close, A. V. Barker, and A. Allanore. 2019. “Fertilizing Properties of Potassium Feldspar Altered Hydrothermally.” Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 50 (4): 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2019.1566922

Das, S., B. Mitra, A. Saha, S. Mandal, P. K. Paul, M. El-Sharnouby, M. M. Hassan, S. Maitra, and A. Hossain. 2021. “Evaluation of Quality Parameters of Seven Processing Type Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cultivars in the Eastern Sub-Himalayan Plains.” Foods 10 (5): 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10051138

Davenport, J. R., and E. M. Bentley. 2001. “Does potassium fertilizer form, source, and time of application influence potato yield and quality in the Columbia Basin?” American Journal of Potato Research 78 (4): 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02875696

Fernandes, A. M., R. P. Soratto, L. D. A. Moreno, and R. M. Evangelista. 2015. “Effect of Phosphorus Nutrition on Quality of Fresh Tuber of Potato Cultivars.” Bragantia 74: 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4499.0330

Foley, J. A., N. Ramankutty, and D. Zaks. 2011. “Solutions for a Cultivated Planet.” Nature 478: 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10452

Haddad, M., N. M. Bani-Hani, J. A. Al-Tabbal, and A. H. Al-Fraihat. 2016. “Effect of Different Potassium Nitrate Levels on Yield and Quality of Potato Tubers.” Journal of Food, Agriculture and Environment 14 (1): 101–107.

Hochmuth, G. J., and E. A. Hanlon. (1996) 2016. “Commercial Vegetable Fertilization Principles: SL319/CV009, 6/2016.” EDIS 2016 (6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv009-1996

Hopkins, B. G., T. Stark, and K. A. Kelling. 2020. “Nutrient Management.” In Potato Production Systems, edited by J. C. Stark, M. Thornton, and P. Nolte. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39157-7_8

Hutchinson, C. M., E. H. Simonne, G. Hochmuth, W. M. Stall, S. M. Olson, S. E. Webb, T. G. Taylor, and S. A. Smith. 2008. “Potato Production in Florida.” In Vegetable Production Handbook for Florida, 2007–2008, edited by S. M. Olson and E. H. Simonne. Florida Cooperative Extension Service.

Joshi, M., E. Fogelman, E. Belausov, and I. Ginzberg. 2016. “Potato Root System Development and Factors that Determine Its Architecture.” Journal of Plant Physiology 205: 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2016.08.014

Koch, M., M. Naumann, E. Pawelzik, A. Gransee, and H. Thiel. 2020. “The Importance of Nutrient Management for Potato Production Part I: Plant Nutrition and Yield.” Potato Research 63 (1): 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-019-09431-2

Laboski, C. A. 2008. “Understanding Salt Index of Fertilizers.” In Proceedings of the 2008 Wisconsin Fertilizer, Aglime and Pest Management Conference, Madison, Wisconsin, January 15–17, 2008, Vol. 47, 37–41. Cooperative Extension University of Wisconsin. https://soilsextension.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/68/2014/02/2008_wfapm_proc.pdf

Laboski, C. A., J. B. Peters, and L. G. Bundy. 2006. Nutrient Application Guidelines for Field, Vegetable, and Fruit Crops in Wisconsin. A2809. Cooperative Extension of the University of Wisconsin-Extension. Archived at UNT Digital Libraries, January 16, 2009. https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/allcollections/20090115182647/http:/learningstore.uwex.edu/pdf/A2809.pdf

Ludwig, J. W. 1985. Quality Standards for the Processing Industry. International Agricultural Centre.

Marton, L. 2001. “Potassium Effects on Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Yield.” Journal of Potassium 1 (4): 89–92.

Ministry of Agriculture (MoA). 2007. “Challenges in Potato Research.” In The National Policy on Potato Industry, Presentation during the Potato Stakeholders Meeting at KARI Headquarters, Nairobi, Kenya.

Mortvedt, J. J. 2001. “Calculating Salt Index.” Fluid Journal 9 (2): 8–11.

Mosaic. n.d. “High yield potatoes have high nitrogen and potassium needs.” Accessed February 11, 2023. https://www.cropnutrition.com/resource-library/high-yield-potatoes-have-high-nitrogen-and-potassium-needs

Moyano, P. C., E. Troncoso, and F. Pedreschi. 2007. “Modeling Texture Kinetics During Thermal Processing of Potato Products.” Journal of Food Science 72 (2): E102–E107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00267.x

Murphy, H. J., and M. J. Goven. 1966. “The Last Decade in 38 Years of Potash Studies for Potato Fertilizers in Maine.” American Potato Journal 43: 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862621

Naik, P. S. 2005. “Role of Potato in Food and Nutritional Security in Developing Countries with Special Reference to India.” Cancer Imaging Program’s Newsletter 2: 5–8.

Nelson, D. C., J. R. Sowokinos, and R. H. Johansen. 1984. “The Use of Sucrose to Predict the Value of Potato Varieties for Processing.” North Dakota Farm Research 41 (6): 11–13. http://hdl.handle.net/10365/5561

Olaitan, S. O., and G. Lombin. 1984. Introduction to Tropical Soil Science. Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Otieno, H. M., and E. K. Mageto. 2021. “A Review on Yield Response to Nitrogen, Potassium and Manure Applications in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Production.” Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science 6 (1): 80–86. https://doi.org/10.26832/24566632.2021.0601011

Panique, E., K. A. Kelling, E. E. Schulte, D. E. Hero, W. R. Stevenson, and R. V. James. 1997. “Potassium Rate and Source Effects on Potato Yield, Quality, and Disease Interaction.” American Potato Journal 74: 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02852777

Perrenoud, S. 1993. IPI Bulletin 8. Fertilizing for High Yield Potato. 2nd ed. International Potash Institute. https://www.ipipotash.org/uploads/udocs/ipi_bulletin_8_fertilizing_for_high_yield_potato.pdf

Pistilli, M. 2022. “Top 10 Countries for Rare Earth Metal Production.” Rare Earth Investing News, September 19. Archived at Wayback Machine, December 20, 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20221220090203/https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/critical-metals-investing/rare-earth-investing/rare-earth-metal-production/

Reiners, S., Q. M. Ketterings, and K. Czymmek. 2019. Nutrient Guidelines for Vegetables. Animal Science Publication Series No. 249. Cornell University. http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/publications/files/VegetableGuidelines2019.pdf

Rosen, C. J. 2021. “Potato Fertilization on Irrigated Soils.” University of Minnesota Extension. https://extension.umn.edu/crop-specific-needs/potato-fertilization-irrigated-soils

Rosen, C. J., K. A. Kelling, J. C. Stark, and G. A. Porter. 2015. “Optimizing Phosphorus Fertilizer Management in Potato Production.” American Journal of Potato Research 91: 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-014-9371-2

Saravia, D., E. R. Farfán-Vignolo, R. Gutiérrez, F. De Mendiburu, R. Schafleitner, M. Bonierbale, and M. A. Khan. 2016. “Yield and physiological response of potatoes indicate different strategies to cope with drought stress and nitrogen fertilization.” American Journal of Potato Research 93 (3): 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-016-9505-9

Schippers, P. A. 1968. “The Influence of Rates of Nitrogen and Potassium Application on the Yield and Specific Gravity of Four Potato Varieties.” European Potato Journal 11: 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02365159

Schulze, D. G. 2005. “Clay Mineralogy.” In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment, edited by D. Hillel, Vol. 1. Elsevier, Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-348530-4/00189-2

Sharma, R. C., and K. C. Sud. 2001. Potassium Management for Yield and Quality of Potato. International Potash Institute. https://www.ipipotash.org/uploads/udocs/Potassium%20Management%20%20Potato.pdf

Šimková, D., J. Lachman, K. Hamouz, and B. Vokal. 2013. “Effect of Cultivar, Location and Year on Total Starch, Amylose, Phosphorus Content and Starch Grain Size of High Starch Potato Cultivars for Food and Industrial Processing.” Food Chemistry 141 (4): 3872–3880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.080

Sparks, D. L. 2000. “Bioavailability of Soil Potassium.” In Handbook of Soil Science, edited by M. E. Sumner. CRC Press.

Swaminathan, M. S. 2001. “Potato for Global Food Security.” In Potato: Global Research and Development, edited by S. M. P. Khurana, G. S. Shekhawat, B. P. Singh, and S. K. Pandey, Vol I. Indian Potato Association.

Thompson, M. V., and M. A. Zwieniecki. 2005. “The Role of Potassium in Long Distance Transport in Plants.” In Vascular Transport in Plants, edited by N. M. Holbrook and M. A. Zwieniecki. Elsevier, Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012088457-5/50013-7

Torabian, S., S. Farhangi-Abriz, R. Qin, C. Noulas, V. Sathuvalli, B. Charlton, and D. A. Loka. 2021. “Potassium: A Vital Macronutrient in Potato Production—A Review.” Agronomy 11 (3): 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11030543

Uchida, R. 2000. “Essential Nutrients for Plant Growth: Nutrient Functions and Deficiency Symptoms.” In Plant Nutrient Management in Hawaii’s Soils, edited by J. A. Silva and R. S. Uchida. University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/40e471a4-9d1c-4ea4-ae29-b8a785a13742/content

USDA-NASS. 2024a. 2023 State Agriculture Overview of Florida. Last accessed December 13, 2024. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/Ag_Overview/stateOverview.php?state=FLORIDA

USDA-NASS. 2024b. Crop Production 2023 Summary. https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/k3569432s/ns065v292/tm70ph00b/cropan24.pdf

Warncke, D., J. Dahl, and B. Zandstra. 2004. Nutrient Recommendations for Vegetable Crops in Michigan. Extension Bulletin E2934. Michigan State University Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/fertrec/uploads/E-2934-MSU-Nutrient-recomdns-veg-crops.pdf

Zotarelli, L., T. Wade, G. England, and C. Christensen. 2021. “Nitrogen Fertilization Guidelines for Potato Production in Florida: HS1429, 12/2021.” EDIS 2021 (6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1429-2021