Introduction

Cover crops (CCs) are broadly defined as plants grown for the enrichment and protection of the soil, rather than for the sole purpose of being harvested. They have a long history in agriculture, dating back to at least the Roman Empire when farmers grew legumes to improve soil fertility. In the 1800s through the early 1900s, farmers in the United States often planted CCs for both fertility and erosion control (Ingels and Klonsky 1998). However, CC use declined after the introduction of synthetic fertilizers. Recently, CCs have regained popularity as interest in soil health and agricultural sustainability increases among growers and consumers. Cover crops are becoming a widespread practice in annual cropping systems (e.g., corn, soybean, cotton, etc.). However, their use in perennial agroecosystems and within subtropical climates is less common due to the climatic conditions and management practices of perennial systems. The aim of this publication is to provide Extension agents and growers with practical information to help them successfully cultivate CCs in Florida citrus groves.

Cover crops provide multiple ecological and economic benefits to agricultural production, including weed suppression, soil organic matter (SOM) formation, erosion control, water and nutrient retention, reduced mowing frequency of row middles, and increased soil microbial abundance and activity. Soil microbes are responsible for nutrient cycling and can protect plants from biotic and abiotic stressors. Together, over time, these benefits can improve soil health, potentially reduce fertilizer inputs, and lead to improved crop yields and more sustainable agricultural systems.

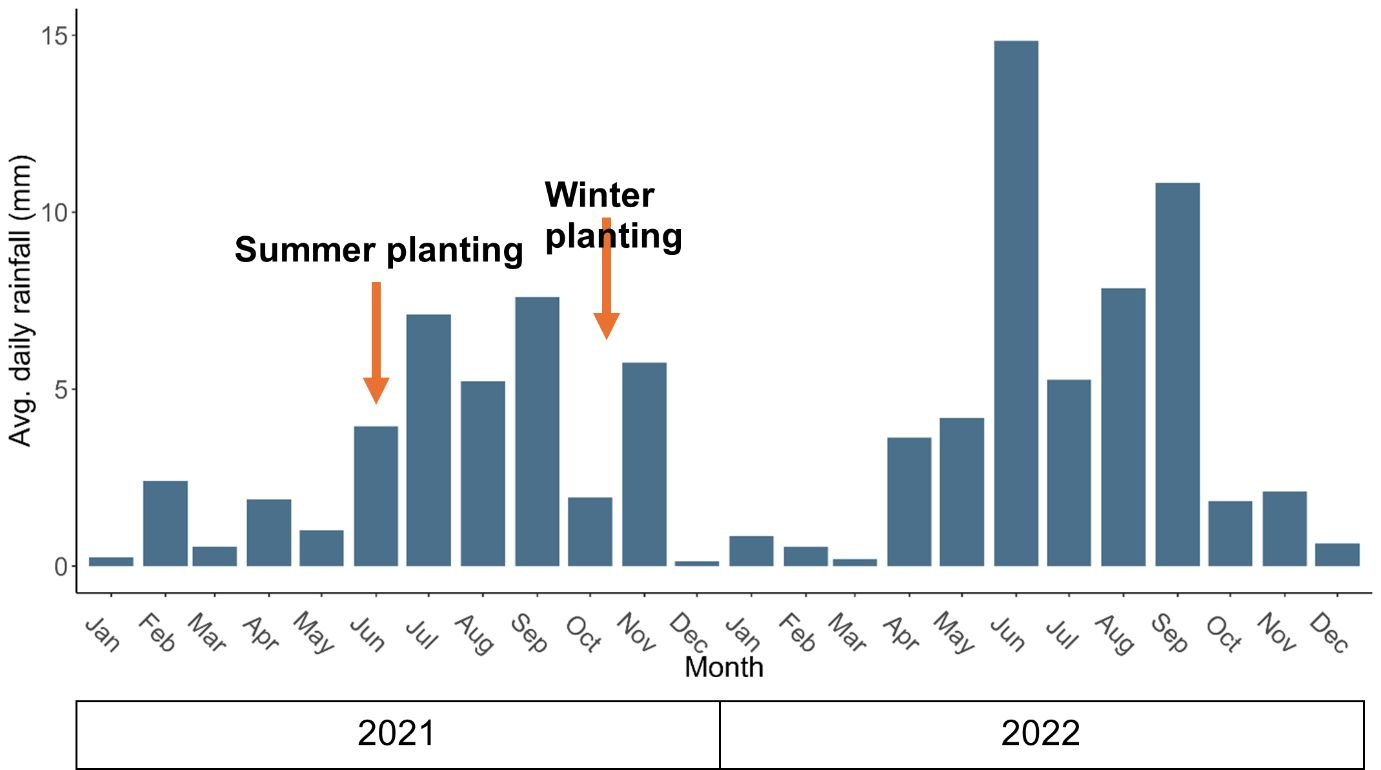

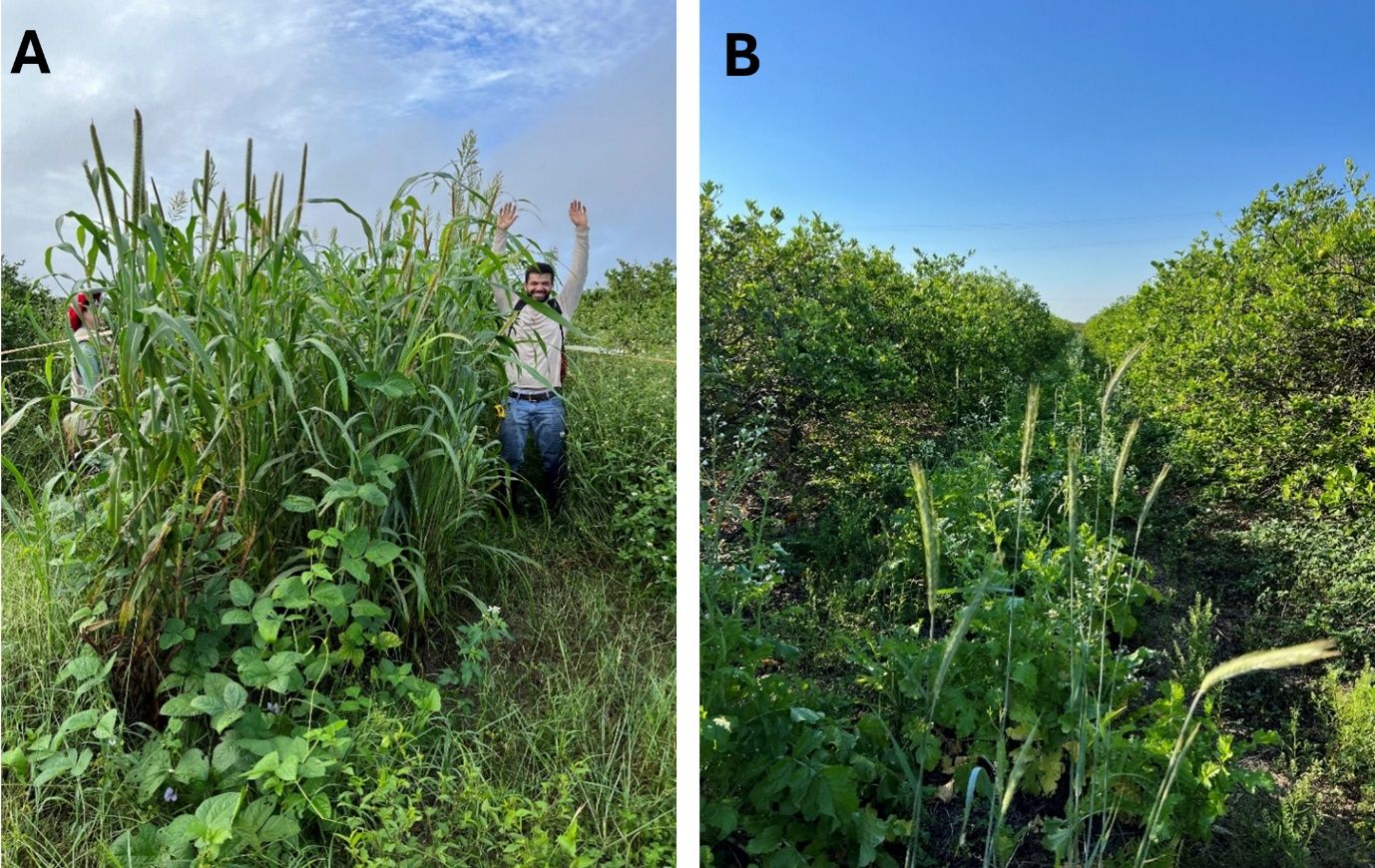

However, there are challenges to growing CCs in Florida perennial crops that are not present when growing CCs in annual cash crops in temperate climates. These challenges include year-round warm temperatures, extreme seasonal variations in water availability (Figure 2), sandy, nutrient-limited soil, and planting and equipment constraints. In south Florida (flatwoods region), citrus crops are planted on raised beds (Figure 1A). Each raised bed consists of a row middle with tree rows on either side and a swale on the opposite side of the trees (Figure 1A). When trees are planted in a raised bed design, CCs can often only be planted on one side of the trees due to the difficulty of planting within the swales. In the Mid-Florida Ridge region, trees are planted on flat ground with no swales. This allows CCs to be planted on both sides of the tree row (Figure 1B). Unlike in annual cropping systems, CCs generally cannot be planted directly adjacent to trees due to the tree canopy. Depending on the size of the trees, it can be difficult to maneuver tractors within the row middles. Additional care should be taken to avoid damaging trees and their roots, so unlike in annual crops where cover crops may be tilled in at the end of the season, tillage is often minimal in perennial systems. Due to the subtropical climate in Florida, CCs can also be grown year-round in citrus. This can provide soil with added benefits but requires more planning and coordination to plant and terminate CCs at the appropriate times.

Credit: (A) Kevin Hill, UF/IFAS. (B) Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS.

Credit: Emma Dawson, Davie Kadyampakeni, Ramdas Kanissery, Tara Wade, and Sarah L. Strauss, UF/IFAS.

Despite the challenges of cover cropping in citrus, it is generally better to keep the soil covered with beneficial plants than to leave it bare. The growing interest in soil health and the need for cultural practices that could improve citrus tree health in HLB (Huanglongbing; citrus greening disease)-affected regions have prompted both growers and researchers to investigate the use of CCs in citrus.

What to Plant

Cover crops can be planted alone as a monoculture, or as part of a multispecies mix. Both options provide multiple benefits to an agroecosystem. The choice between the two depends on the grower’s goals, resources, and financial considerations. Monocultures tend to be more economical but may not provide all the potential benefits to the soil of a mixture. For example, grass species such as sorghum or rye are popular choices for monoculture planting because of their ability to produce high quantities of biomass. A monoculture of rye can provide good weed suppression and erosion control but may not impact soil fertility or biology as much as a grass + legume mixture (Castellano-Hinojosa et al. 2023). However, mixtures can become costly and require additional planning to implement properly. When planting a mixture, seeding rates need to be adjusted to consider multiple species, and seed drills must be properly calibrated to account for different seed sizes. However, both monocultures and mixtures are excellent options for suppressing weeds, building SOM, and enhancing soil microbial communities.

Cover crop species selection depends on the grower's overall objective. If the primary purpose of the CC is to prevent erosion and produce large amounts of biomass, then planting a grass monocrop may be the simplest and most affordable option. If a grower would like to increase SOM and nitrogen (N) cycling in their soil, in addition to decreasing erosion, then planting a mixture of legumes and non-legume grasses may be more beneficial.

To begin building a CC mixture, it is recommended to choose plants from multiple functional groups, such as monocot grasses, legumes, and broadleaf species. This reduces competition between species within the same group and increases the environmental benefits provided by the mixture (Chapagain et al. 2020). The carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of each CC species and that of the total mixture are other factors to consider. The C:N ratios will alter biomass decomposition, SOM accumulation, and nutrient cycling. For example, C:N ratios below 25:1 lead to more rapid mineralization of nutrients, which can then be used by plants. High C:N ratios (>30:1) increase immobilization of nutrients, which makes them unavailable for immediate plant uptake. More information about CC species successfully grown in south Florida and their C:N estimates are in Table 1.

Recommended monoculture seeding rates are often provided by the seed supplier or local Extension offices. Seeding rates are based on average germination percentage or live seed for each species. These rates need to be adjusted when planting CCs in mixtures. Different approaches can be used when constructing these mixes. An additive approach where monoculture seeding rates are kept the same in a mixture may be simpler, but it will result in higher costs and increased plant density due to the higher seeding rate. A replacement approach considers the number of species to be included in a mix and divides monoculture rates by the total number of species (Bybee-Finley et al. 2022). Each divided value is then summed for a final planting rate. For example, if one species within a four-species mix has a seeding rate of 40 lb/acre, the seeding rate in the mixture would be 10 lb/acre. Another strategy for selecting seeding rates involves selecting your planting rate and then basing the proportion of each CC to be included on your desired outcome. For example, if you are planting a mix at a rate of 60 lb/acre with a specific interest in N cycling, you may choose to make your mix 50% legumes, so you would include 30 lb of legume seeds and 30 lb of non-legume seeds in this mixture.

To maintain year-round soil coverage while reducing the time, labor, and cost associated with multiple CC plantings, a perennial CC may be a good option. There are fewer perennial CC species available, and they have been used in fewer research trials than annual CCs. However, rhizoma perennial peanut (Arachis glabrata) and pintoi peanut (Arachis pintoi) are two legume species that are successfully grown in south Florida (Rouse et al. 2001). Bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum) is a popular choice for a non-legume perennial CC.

When to Plant

Florida’s subtropical climate creates two distinct seasons based on rainfall: dry winters followed by extremely wet summers. Cover crops are generally not irrigated, so planting success relies primarily on precipitation and planting method. Based on research trials in commercial Florida citrus groves, planting annual CCs should be done at least twice a year if year-round soil coverage is desired. Summer CCs are typically planted in June, at the start of the rainy season, while winter CCs are planted between October and November to capture the end of Florida’s rainy season (Figure 2) and allow for CC establishment before the dry season.

Credit: Sarah Strauss, UF/IFAS

How to Plant

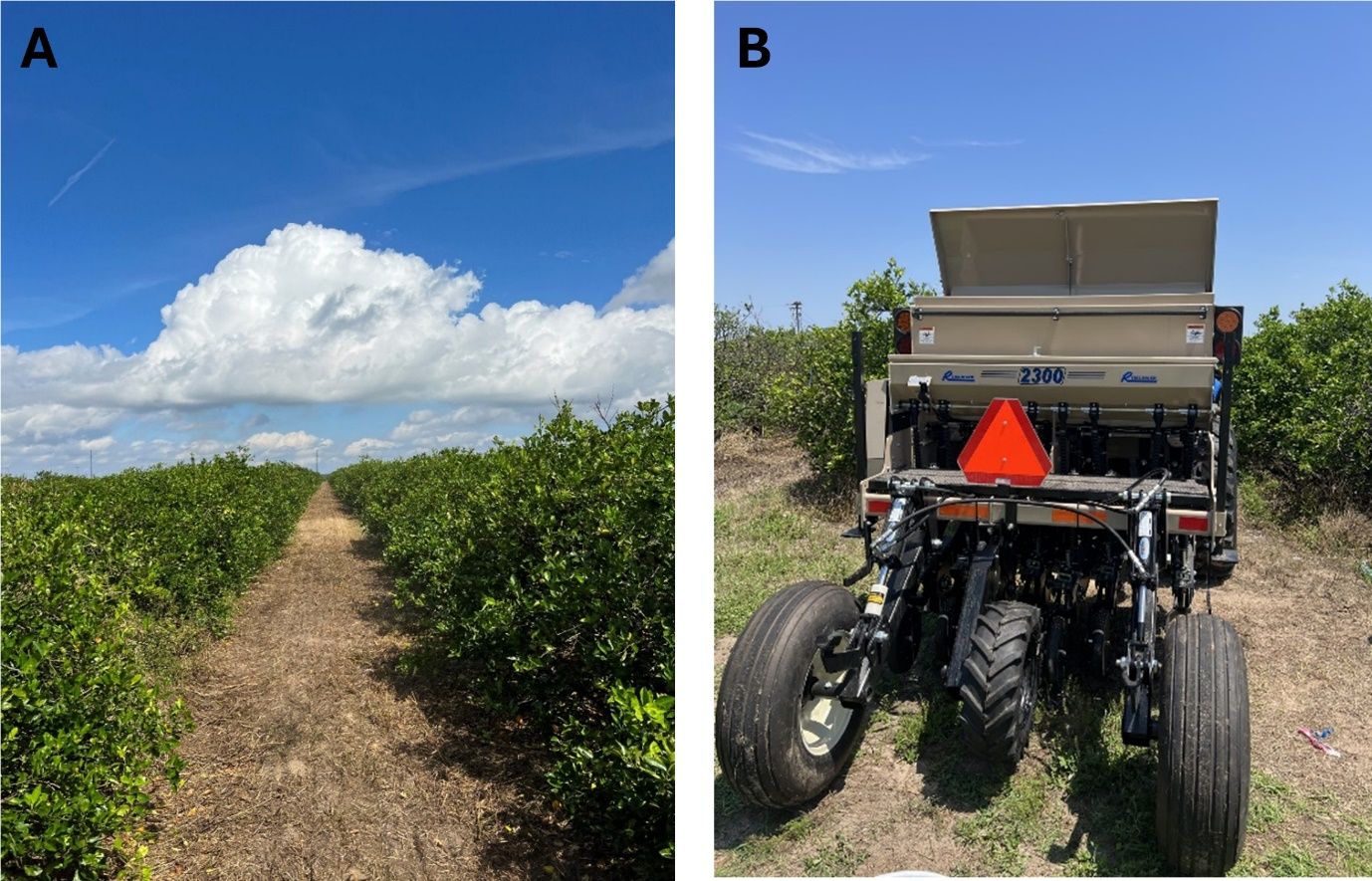

Once you have chosen what CCs to plant and decided when to plant them, the next step is putting seeds in the ground. Before planting, citrus row middles can be treated with herbicide, such as glyphosate or paraquat, and mowed (Figure 4) to remove unwanted vegetation or weeds. When glyphosate is applied, it is advisable to wait 1 to 2 weeks before planting cover crops, if possible. This waiting period helps minimize any potential impacts on CC germination and establishment. If there is significant weed pressure or concern about CC germination, a shallow discing can be done to further prepare the soil with limited damage to tree roots. In some cases, all three strategies can be used to improve planting conditions and increase the chances of successful CC germination and growth. Seed mixtures in UF/IFAS experiments have been planted using a no-till drill (Figure 4) to avoid damaging tree roots. Seed drills should be properly calibrated based on the desired planting rate and seed size prior to planting. If a seed drill is not available, broadcasting is another planting method that may be used. Broadcasted seed are thrown out over the soil surface instead of being drilled in. If this method is used, planting rates should be adjusted for broadcasting seeds. The recommended rates with this method are typically higher than drilled rates to account for seed loss and reduced germination. While not ideal, broadcasting can be useful when access to a seed drill is unavailable or when equipment fails to fit into row middles.

Credit: Emma Dawson, UF/IFAS

Cover Crop Termination

When planting CCs twice annually (summer and winter), CCs from the previous planting may need to be terminated prior to the next planting. Termination is the act of killing a CC either chemically with herbicides or mechanically using a mower or roller-crimper. Mechanical termination can be useful when herbicides are not an option, such as in organic systems. Mechanical termination success is highly dependent on the timing of termination and the CC biomass present. Termination timing can impact subsequent rates of CC decomposition and nutrient cycling. In annual cropping systems, it is often recommended to terminate CCs when they are mature but before seed set. This ensures that biomass is high in nutrients but helps to prevent CC seeds from becoming weeds in the next season. In this case, grass CCs are typically terminated before the jointing stage, when the grass internodes start to elongate and form a main stem. For legume CCs, it is best to terminate before the stems elongate and become woody. However, if you are interested in growing year-round CCs, waiting to terminate until after seed set can help to build up a CC seed bank in the soil, potentially reducing the amount of seeds needed in the future.

Cover Crops and Soil Microbes in Citrus Groves

Cover crops have a wide range of reported benefits; however, these benefits may take several years to accrue. This is more likely to be the case in citrus than other crops due to grove age, as most management changes are unlikely to quickly impact 10- to 20+-year-old trees. If CCs are implemented when trees are young, changes may be more noticeable. Years of prior management decisions have shaped soil physical, chemical, and biological properties, so it can take time for CC impacts to overcome previous practices. While changes to soil nutrients or SOM may not be immediately obvious, reduced erosion, weed suppression, and alterations within the soil microbial community can occur rapidly. For example, the soil microbial community is partially responsible for biomass decomposition and a range of nutrient transformations, including N mineralization, nitrification, and denitrification (Nevins et al. 2020). In past experimental trials, the abundance of N-cycling microbial genes increased after only 3 years of CCs (Castellano-Hinojosa et al. 2023).

Despite only being planted within citrus row middles, CCs can also alter the microbial community associated with tree roots (i.e., the rhizosphere) through alterations in the bulk soil microbial community (Dawson et al., in review). In the rhizosphere, plants recruit soil microbes that may have positive plant growth-promoting properties. Changes to the citrus rhizosphere may support tree growth and development because of the presence of these plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) such as N-fixing and phosphorus-solubilizing microbes. These PGPB can help to support trees during biotic and abiotic stress events.

Summary of Cover Crop Suggestions

Benefits of Cover Crops

Benefits of planting CCs range from ecological to economical and include weed suppression, soil organic matter (SOM) formation, erosion control, water and nutrient retention, reduced mowing frequency of row middles, and increased soil microbial abundance and activity. Over time, CC benefits can improve soil health, potentially reduce fertilizer inputs, and lead to improved crop yields and more sustainable agricultural systems.

What to Plant

Monocultures (single cover crop species) or mixtures can both be beneficial. The grower’s goals, resources, and financial considerations can determine which is more appropriate. To prevent erosion and produce large amounts of biomass, planting a grass monocrop can be a good option. To increase SOM and nitrogen (N) cycling and decrease erosion, planting a mixture of legumes and non-legume grasses may be more beneficial. Seed suppliers and local Extension offices can provide recommended seeding rates.

When to Plant

To avoid having to irrigate cover crops, it is helpful to time plantings to occur during the rainy season.

How to Plant

It can be helpful to treat row middles before planting cover crops with herbicide, such as glyphosate or paraquat, and/or to mow in order to remove unwanted vegetation or weeds. Cover crops can be planted either by using a seed drill (ideally a no-till drill to reduce impact to citrus roots) or by broadcasting. Seed drills should be properly calibrated based on the desired planting rate and seed size prior to planting.

Cover Crop Termination

Before planting the next round of CCs, the previous CCs may need to be terminated either chemically with herbicides or mechanically using a mower or roller-crimper. However, if you are interested in growing year-round CCs, note that delaying termination until after seed set can help to build up a CC seed bank in the soil, potentially reducing the number of seeds needed in the future.

References

Bybee‐Finley, K. A., S. Cordeau, S. Yvoz, S. B. Mirsky, and M. R. Ryan. 2022. “Finding the Right Mix: A Framework for Selecting Seeding Rates for Cover Crop Mixtures.” Ecological Applications 32(1): e02484. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2484

Castellano-Hinojosa, A., R. Kanissery, and S. L. Strauss. 2023. “Cover crops in citrus orchards impact soil nutrient cycling and the soil microbiome after three years but effects are site-specific.” Biology and Fertility of Soils: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-023-01729-1

Chapagain, T., E. A. Lee, and M. N. Raizada. 2020. “The Potential of Multi-species Mixtures to Diversify Cover Crop Benefits.” Sustainability 12(5): 2058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052058

Ingels, C. A., and K. M. Klonsky. 1998. “Historical and Current Uses.” In Cover Cropping in Vineyards: A Grower's Handbook. 3–7. University of California.

Nevins, C. J., S. L. Strauss, and P. Inglett. 2020. “An Overview of Key Soil Nitrogen Cycling Transformations: SL471/SS684, 5/2020.” EDIS 2020(3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss684-2020

Rouse, R. E., R. M. Muchovej, and J. J. Mullahey. 2001. “Guide to Using Perennial Peanut as a Cover Crop in Citrus.” EDIS.

Table 1. Commonly used cover crop species in southwest Florida.