Florida's Flat-footed Falcon

Breeding = spring, fall, winter

Habitat = grassland

Status = threatened

Scientific name: Caracara cheriway (previously Polyborus plancus audubonii)

Common name: Northern Crested Caracara

Habitat: dry prairie, improved pastures

Physical Description: Black and white large bird of prey with yellow-orange skin on legs and face and a blue-grey hooked beak. A toupee-like black cap and crest contrasts strongly with its white neck and cheeks. In flight, the undertail and outer flight feathers contain white panels. Juveniles are brown and cream and lack the adults' intense yellow-orange legs and faces. Males and females look similar and females are slightly larger. They have a wingspan of up to 40 inches and stand to approximately 20 inches.

Weight: 37 to 45 oz

Reproductive Rate: Average 2–3 eggs with 28–30 day incubation and young fledge at around 7–8 weeks old. Caracara pairs can make more than one nesting attempt in a breeding season.

Lifespan: Captive crested caracaras have lived for over 30 years. The lifespan of wild crested caracaras is unknown, but the oldest in Florida lived for at least 24 years.

Dispersal & Home Range: Evidence suggests that caracaras do not usually move very far between birth and the first time they reproduce as adults. Females have been observed dispersing farther than males, an average of 14 versus 4 miles. Established breeding pairs use an average of 6 square miles around their nests. Single adults use five times as much area as breeding pairs during non-breeding season and up to 250 times the area during the breeding season.

Credit: Isabel Gottlieb

Biology and Behavior

Caracaras are members of the falcon family, which includes many agile and speedy aerial hunters; however, they are often seen foraging on the ground, walking on their large, strong legs. Caracaras are opportunistic carnivores and will eat practically any living or dead animal matter, including insects, reptiles, amphibians, fish, smaller birds, and mammals. They can often be found feeding alongside vultures on carrion or roadkill. Peak breeding occurs in the dry months from November to April, and egg-laying often follows the sharp decline of precipitation that usually happens in the fall. Even though they may be harder to spot outside the breeding season, mated pairs remain in their territory year round and often nest in the same area and even the same tree year after year. After leaving the nest, fledglings chase their parents around, begging for food. Approximately one third of independent young will survive to breed in a few years, typically starting at age three. In the time between leaving their parental territories and breeding, these young individuals congregate in large groups at three known locations in south-central Florida, one along the Kissimmee River, north of State Route 98, one in Glades County north of US Highway 27, and one near Eagle Island Road in Okeechobee County. These congregation areas are composed mostly of large areas of improved pastures.

Credit: Jean Hall

Fast Facts

- Unlike other raptors that kill prey with their talons, Caracara often jump on prey on the ground, kill them, and then carry them with their beaks.

- Caracara talons and toes are flatter than those of other members of the falcon family, which allows them to walk and run along the ground more easily.

- Caracaras regurgitate items they cannot digest, producing pellets that contain insect exoskeletons, animal hair, and plant matter.

- Young individuals can congregate and roost in groups of up to several hundred individuals.

History and Habitat

Caracaras are residents of grasslands. Historical accounts of crested caracaras show an association with prairie-type habitats in central and southern Florida. Early records from the 19th century are anecdotal and spotty but suggest that caracaras inhabited a larger area in the state than at present. The first specimen collected by Audubon was from Saint Augustine, which is outside of the current range. Dry prairie habitat has been largely converted to citrus, sugar, and cattle ranching uses. Despite reduction in native prairie habitat, caracaras have persisted and are now largely found breeding and foraging in improved pastures that have been planted with non-native or exotic grasses for cattle to eat. Within these pastures, the presence of trees, especially cabbage palms, is important because caracaras use them as nest platforms.

Distribution

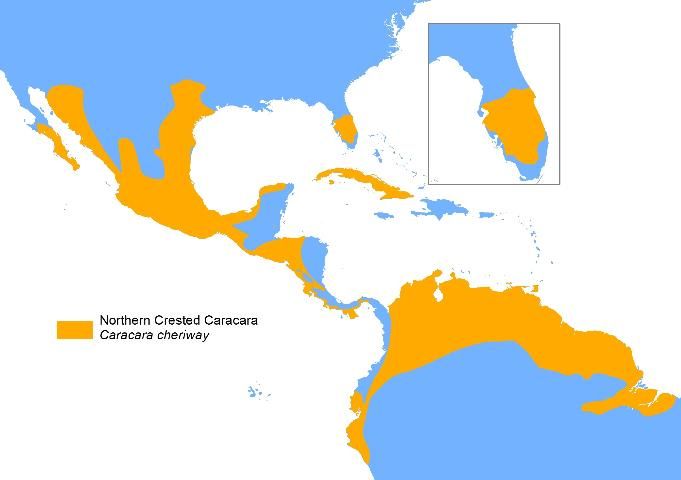

Northern crested caracaras can be found throughout Central America and northern South America as far south as Brazil within suitable grassland habitat. Another very similar caracara species, the southern crested caracara (Cacaraca plancus), resides in central and southern South America. A third species, the insular Guadalupe caracara (Caracara lutosus) is now extinct. In the United States, caracaras are found in Arizona, Texas, and Florida. In Florida, they are most abundant in southern and central portions of the state where they live throughout the year. This Florida population is non-migratory and is distinct from populations in Latin America and the western United States.

Credit: Jean Hall

The Importance of Cattle Ranches to Caracara

In Florida, up to 80% of nesting pairs of northern crested caracara are found on private cattle ranches. In fact, caracaras that breed on lands used for cattle grazing appear to have a higher breeding success and produce more young than those that breed in managed natural habitat. This may be because shorter grass increases visibility and reduces the birds' risk of being killed by other predators, or makes it easier for caracaras to walk around and hunt on the ground. It could also be that these cattle lands provide increased nutrients for insects that become concentrated at dung piles, which the caracara actively flip during hunting. Overall, pasturelands are the most important habitat for the continued survival of this species in Florida, and their conversion to urban land uses is a major threat to northern crested caracaras.

Did you know?

Caracaras flip over cow pies (dry manure) in search of hiding insect prey, like scarab and dung beetles.

Credit: Jean Hall

Timeline

1834: John James Audubon first describes Caracaras (Polyborus vulgaris)

1865: Scientific name changed to Polyborus audubonii

1876: Caracara treated as three species: P. tharus in southern South America, P. cheriway in northern South America to southern North America, and P. lutosus on Guadalupe Island, Mexico.

1906: The Guadalupe caracara (P. lotosus) goes extinct

1920: Increasing conversion of natural habitat for agricultural uses through the 20th century

1930s: Observed declines in Florida caracara population

1949: P. tharus and P. cheriway renamed as P. plancus

1970: Less than 500 breeding adults and young remain

1987: The Florida caracara is considered a sub-species, P. plancus audobonii, and listed as Threatened by USFWS

1992: Polyborus is changed to Caracara

1999: Body measurements of museum birds support splitting caracaras into three separate species, C. cheriway, C. plancus, and C. lutosus

2018: Birdwatching data suggests that the northern crested caracara population has been stable or increased slightly since the 1970s.

For More Information

EDIS Factsheets—https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu

Northern Crested Caracara FWC Species Profile

Crested Caracara at All About Birds/ Cornell Lab of Ornithology

How You Can Help

- Collisions with cars are a significant cause of death for juvenile caracaras. Use caution when driving past roadkill, especially in rangelands in central and south Florida.

- To improve breeding habitat within rangelands, maintain cabbage palms for nesting.