Exploring the World of Hoppers

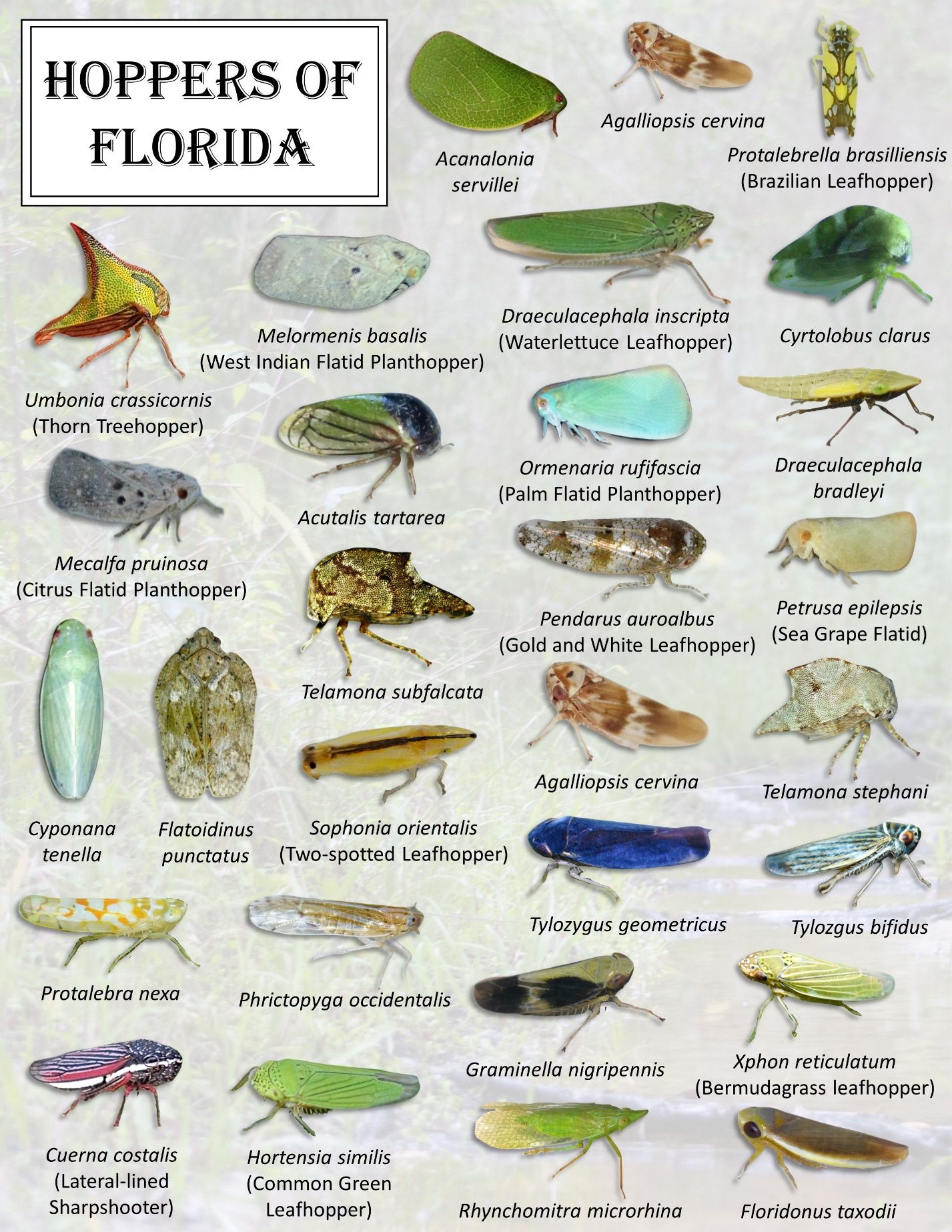

Leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers— which we collectively refer to as “hoppers”—are fascinating insects that are often overlooked in the world of wildlife viewing. These insects are distinct from grasshoppers, which are more commonly recognized but not considered “true hoppers.” Hoppers are closely related to a large group of insects that includes many common insects, such as stinkbugs, cicadas, whiteflies, and many more. These small but diverse creatures (Figure 1) play important roles in ecosystem functioning. Hoppers are not as well-studied or understood as some other insect groups. This guide is aimed at the general public. We hope to introduce you to these remarkable insects and provide information on how to observe, identify, and document them.

Before diving into the fascinating world of hoppers, we must recognize the critical role of citizen science—also referred to as community science—in enriching our understanding of biodiversity. Platforms like iNaturalist (www.inaturalist.org) not only make it easy to document and share observations but also significantly contribute to ongoing research by connecting the public with scientists worldwide. Learning how to observe and document hoppers will open a newfound appreciation for this group of diverse insects and contribute to our understanding of their biodiversity and spatial distribution (Figure 1). Whether you’re a seasoned entomologist or a nature enthusiast, you can make meaningful contributions to science by documenting hoppers and sharing your observations. Each observation becomes a valuable data point, contributing to a better understanding of hoppers and the ecosystems they inhabit. By observing, photographing, and recording information about these organisms, anyone can participate in this scientific endeavor. Our intended audience with this publication is anyone who is interested in the natural world; wants to learn more about finding, identifying, and documenting hoppers; and is interested in contributing to science by adding their observations to iNaturalist.

Credit: Joe Montes de Oca, iNaturalist curator and Corey T. Callaghan, UF/IFAS

The Differences between Leafhoppers, Treehoppers, and Planthoppers

Leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers are three very different groups of insects that exhibit extraordinary variability in appearance, behavior, habitat preference, distribution patterns, and diversity. Grasping the basic taxonomy of leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers is essential for appreciating their ecological roles and accurately documenting their presence, which in turn supports efforts to monitor and conserve biodiversity. Leafhoppers (Cicadellidae), treehoppers (Membracidae), and planthoppers (Fulgoromorpha) all belong to the taxonomic order Hemiptera. Within the order Hemiptera, the hoppers belong to the group (suborder) Auchenorrhyncha. Within this suborder, the leafhoppers and treehoppers belong to the superfamily Cicadomorpha, and the planthoppers belong to the superfamily Fulgoromorpha.

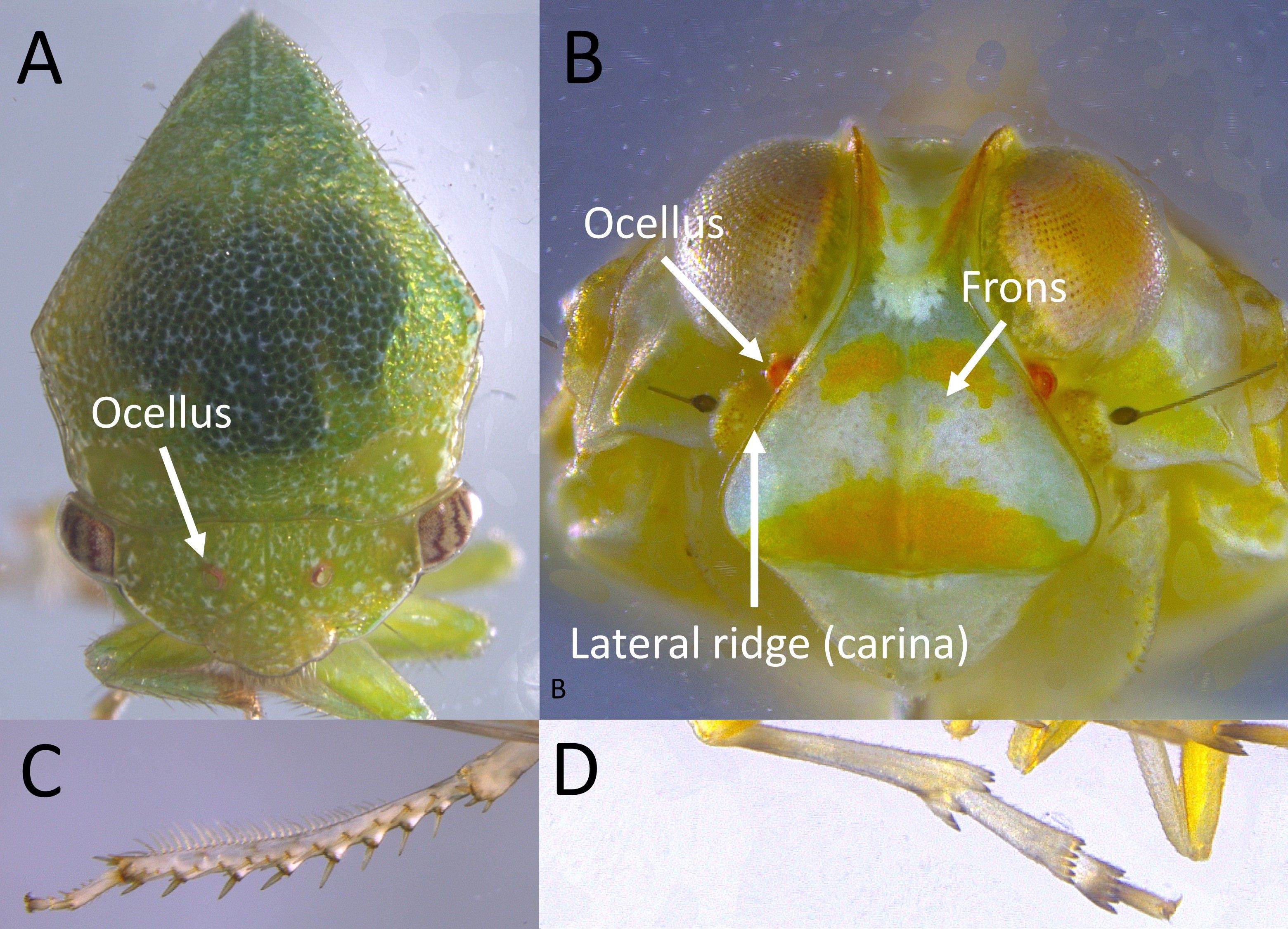

Treehoppers are one of the most easily recognizable groups because they generally have a large spine or projection on the thorax (Figure 2). While not all treehoppers have this feature, neither the leafhoppers nor the planthoppers have enlarged structures of the thorax. Treehoppers also commonly display parental care for their young, a trait that is rare to absent in leafhoppers and planthoppers. Finally, treehoppers are the only group of the three that is restricted to the New World, with Old World records resulting from recent human introductions. Conversely, planthoppers and leafhoppers are highly diverse, globally distributed groups. Leafhoppers belong to the same superfamily as treehoppers and are more similar to treehoppers than to planthoppers, but they differ from both in that they have a long line of uniformly spaced spines along their hind legs. This line of spines on the legs is entirely absent in treehoppers and planthoppers, though some species of planthopper occasionally have a few spines on their hind leg. Planthoppers differ from both treehoppers and leafhoppers in two key features; the first is the presence of two ridges on the face that separate the simple eyes (ocelli) so that they are situated on the sides of the head, a separation not seen in treehoppers or leafhoppers (Figure 2). The second is the presence of a row of paired spines on the second segment of the hind “feet” (tarsi).

Credit: Brian Bahder, UF/IFAS

Using iNaturalist to Document and Identify Hoppers

The citizen science platform iNaturalist, https://www.inaturalist.org/, combines the wonders of nature with the collective efforts of a global community. iNaturalist is an independent platform, allowing participants to contribute observations of any organism, or traces thereof, along with information about where and when that observation took place. The program is free to use and can be accessed via a user-friendly website and mobile app. The key to iNaturalist’s success lies in the precision and thoroughness of the contributed observations. By supplying accurate information about species and locations, contributors add invaluable data points that help researchers, conservationists, and policymakers understand and safeguard the natural world. For these reasons, iNaturalist offers an excellent tool to help fully jump into the world of hoppers. See iNaturalist’s about page and the iNatHelp page for further details on how to get started. Some curated resources are available at iNaturalist contributor @joemdo’s page.

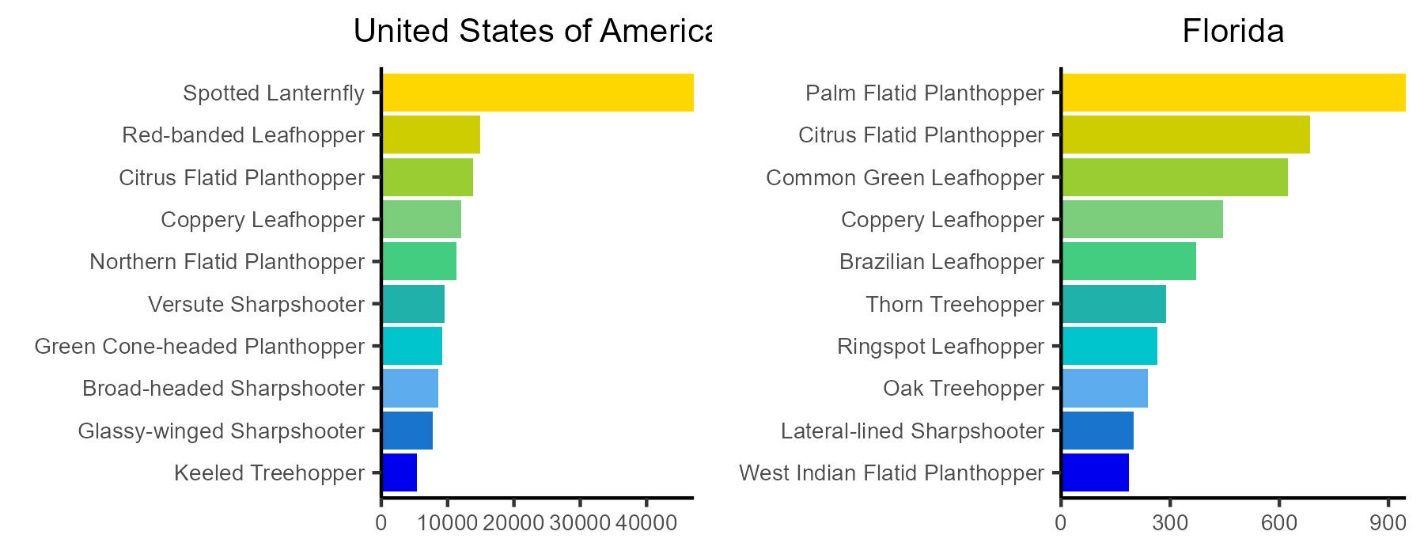

Of the approximately 50,000 documented species of hoppers in the world as of 2023, 5,633 have been submitted to iNaturalist. Per group, that breaks down to approximately 20,000 total species described for leafhoppers, of which 2,910 have been reported to iNaturalist, and approximately 12,000 total species described for planthoppers, of which 2,723 have been reported to iNaturalist. In the United States, 983 leafhopper species, 187 treehopper species, and 429 planthopper species have been submitted to iNaturalist. The most commonly reported hoppers are spotted lanternflies, red-banded leafhoppers, citrus flatid planthoppers, coppery leafhoppers, northern flatid planthoppers, versute sharpshooters, green cone-headed planthoppers, broad-headed sharpshooters, glassy-winged sharpshooters, and keeled treehoppers (Figure 3). In Florida, 158 leafhopper species, 49 treehopper species, and 132 planthopper species have been submitted to iNaturalist. The most commonly reported hoppers in Florida are palm flatid planthoppers, citrus flatid planthoppers, common green leafhoppers, coppery leafhoppers, Brazilian leafhoppers, thorn treehoppers, oak treehoppers, lateral-lined sharpshooters, West Indian flatid planthoppers, and glassy-winged sharpshooters (Figure 3).

Credit:

Observing Hoppers

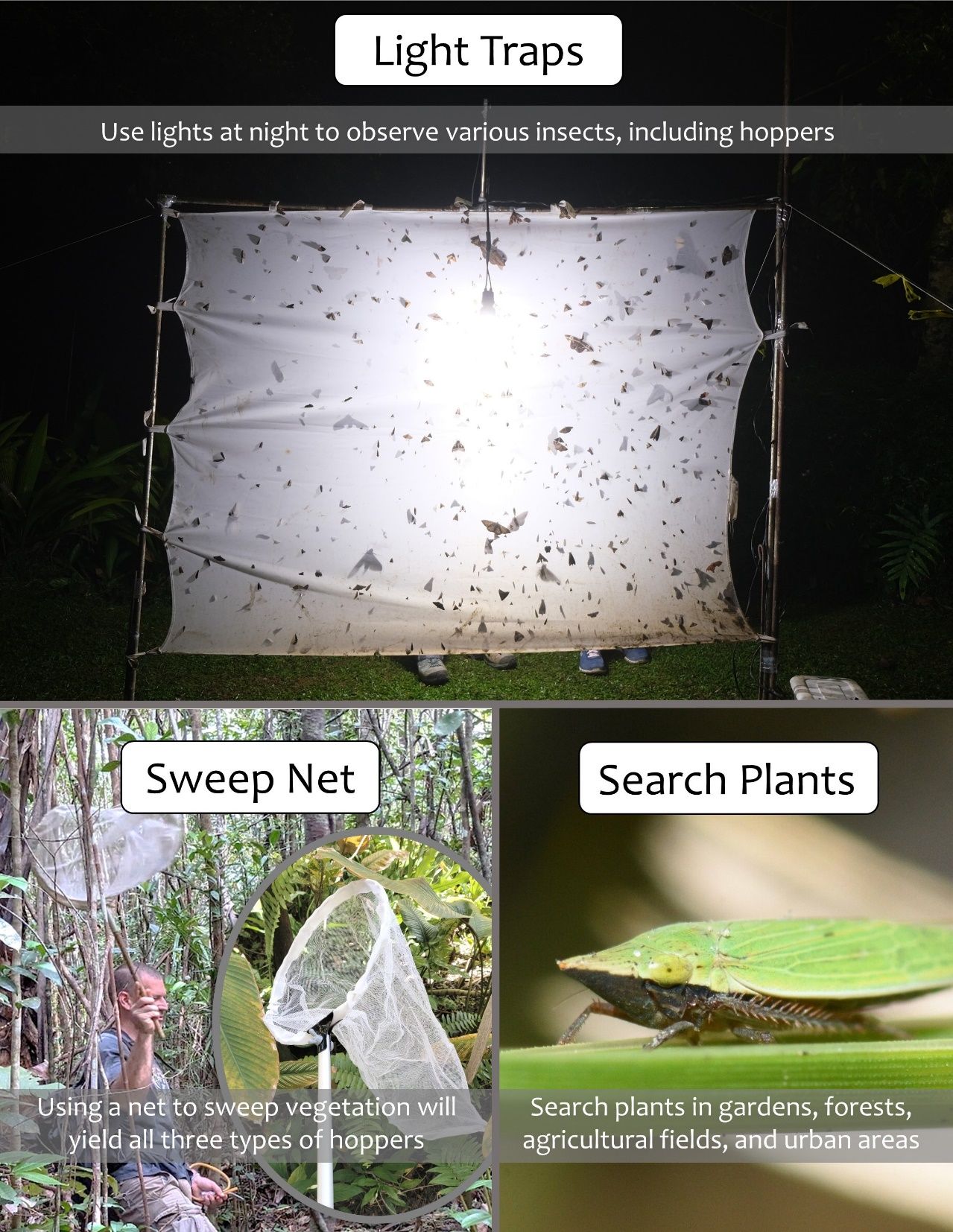

Leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers can be found in various habitats. Their activity patterns may vary depending on the species. These insects are known for their distinctive shapes and behaviors, making them interesting subjects for observation. Although their life histories differ, observers can use similar techniques to find all three groups of hoppers. Some more specialized techniques can be used to maximize documentation of a specific type of hopper (Figure 4). Here are some tips for observing them:

Habitat Selection: Leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers are commonly associated with plants. You can find them in gardens, agricultural fields, forests, and even urban areas. Pay attention to the plants with which they are associated, as different species may prefer specific host plants.

Time of Day: While hoppers are generally active during the day, their cryptic nature and rapid movement when they are disturbed can make them difficult to spot. At night, however, they are attracted to lights. A simple light trap (see below) provides a practical means to observe hoppers alive.

Light traps: Light trapping is a highly effective method for collecting all three groups of hoppers such that both leafhoppers and planthoppers are drawn to artificial lights. A light and sometimes a white sheet is all you need to observe several varied species of insects, including hoppers.

Sweep nets: In general, sweeping random vegetation with a net will ultimately yield all three types of hoppers. Targeting a specific host plant or habitat type my increase the odds of finding a specific group (or species) over others. For example, sweeping grasses increases the odds of collecting leafhoppers over the other two groups. Treehoppers are more readily found on woody dicot plants. Planthoppers, in general, are much rarer than the other two groups, at least in temperate regions, but will be found on similar plant habitat as treehoppers. However, in Florida, especially south of Lake Okeechobee, planthoppers can be found easily by sweeping palm foliage whereas leafhoppers and treehoppers are much less abundant on palms.

Credit: Brian Bahder and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS and Joe Montes de Oca, iNaturalist curator

Best Practices for Taking Photos of Hoppers for Identification

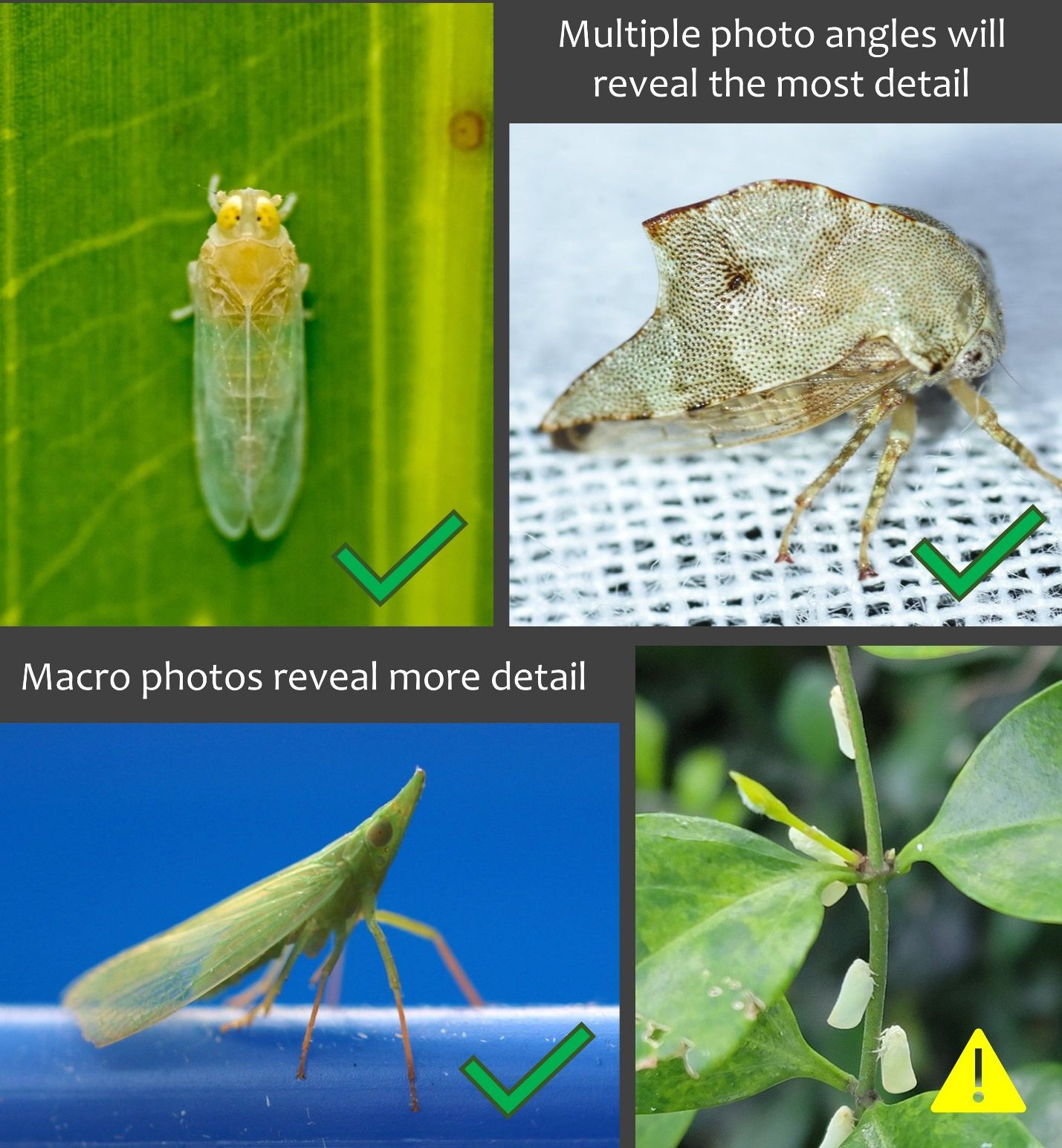

Hoppers can be difficult to identify from snapshots. High quality magnified images are often necessary. We recommend using a camera with macro capabilities or a smartphone with a good camera. You may also want to carry a magnifying glass for close-up inspections. Multiple angles are important for reliable identification (Figure 5).

Credit: De-Fen Mou, Corey Callaghan, and Brittany Mason, UF/IFAS and Joe Montes de Oca, iNaturalist curator

A Deeper Dive on Using iNaturalist to Understand the World of Hoppers

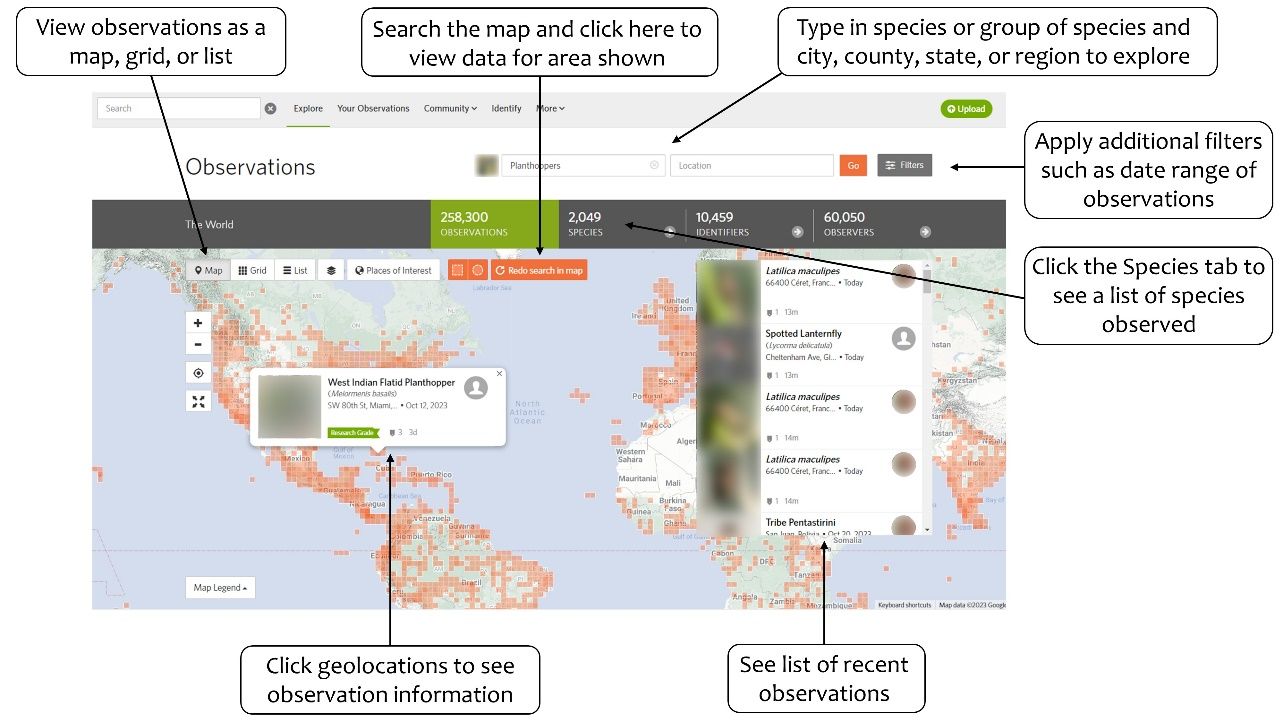

The iNaturalist website is an excellent resource to explore hopper observations worldwide. The best way to explore these species on iNaturalist is through the Explore page. This page features an interactive map that can be filtered by location and species (Figure 6). To explore planthopper species, type “Planthoppers” in the species search bar; similarly, for leafhoppers and treehoppers, type “Leafhoppers and Treehoppers” in the species search bar.

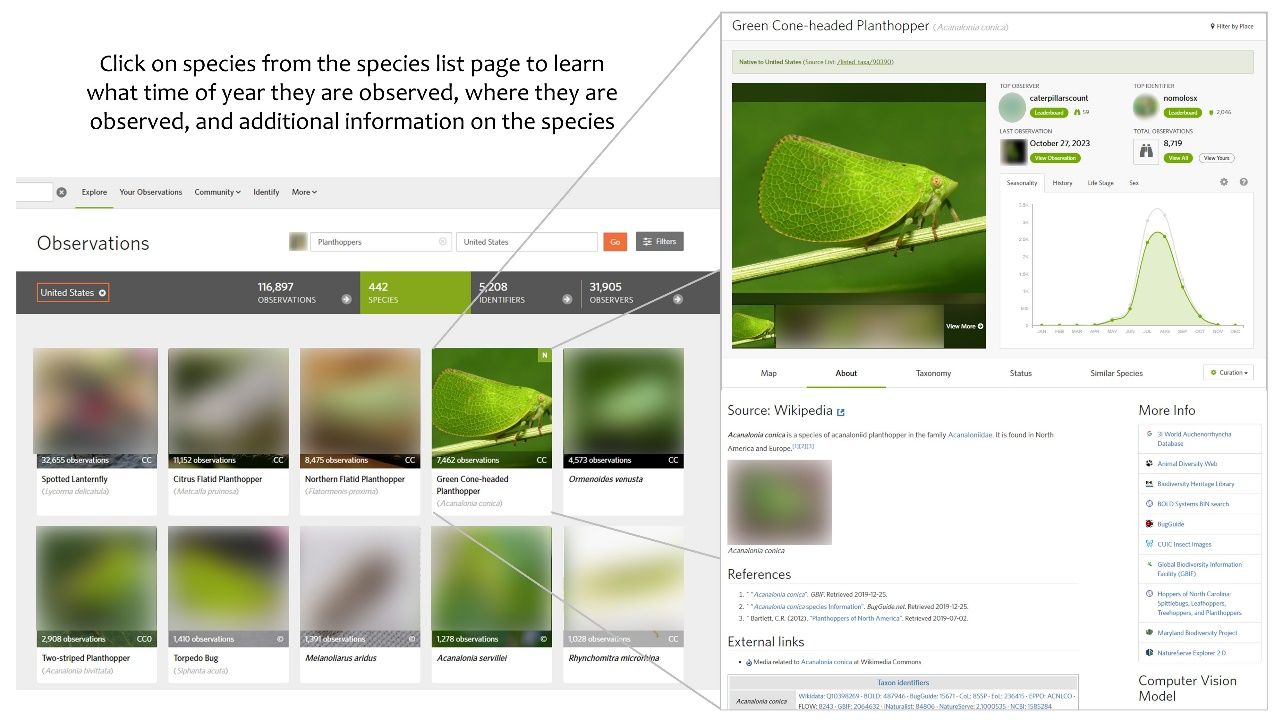

Filter the interactive map to your location using the location box and go to the “Species” tab under “Observations” from the Explore page to see a list of hopper species from your city or local region (Figure 7). Learn more about each species by clicking on their entry. This will direct you to the species’ information page, which contains a graph displaying what time of year a species is most likely to be observed and general information on the species from Wikipedia. The “Map” tab on this page displays an interactive map showing where this species has been observed.

Once you are familiar with hopper identification, consider helping others identify their observations from the Identify page. This page provides a grid view of observations and can be filtered the same as described above from the Explore page (see “How to use the Identify Page” on the iNatHelp Getting Started page for more information). Providing identifications is a great way to engage in the iNaturalist community and learn more about the hopper species in your area. Additionally, identifications increase the value of observations for scientific use (see Callaghan et al. 2022 to learn more).

Credit: Website screenshots from https://www.inaturalist.org.

Credit: Website screenshots from https://www.inaturalist.org and green cone-headed planthopper photo by iNaturalist user Katja Schulz, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 some rights reserved (CC BY 4.0)

Conclusion

Hoppers are a unique group of insects that often go unobserved. However, with practice and dedication, anyone can begin to observe and recognize this diverse group of insects (Figure 1). Our tips are meant to be an introduction into the world of hoppers, and although the data from iNaturalist are useful for such a group, it is important to remember that not all individuals will be identifiable to species (Mesaglio et al. 2023). Nevertheless, we hope that these tools will present you with the ability to learn more about the wonderful world of hoppers!

Additional Resources

More information on leafhoppers from the Illinois Natural History Survey’s Dietrich Leafhopper Lab

References

Callaghan, C. T., T. Mesaglio, J. S. Ascher, T. M. Brooks, A. A. Cabras, M. Chandler, W. K. Cornwell, et al. 2022. “The Benefits of Contributing to the Citizen Science Platform iNaturalist as an Identifier.” PLoS Biology 20 (11): e3001843. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001843

Mesaglio, T., C. T. Callaghan, F. Samonte, S. B. Z. Gorta, and W. K. Cornwell. 2023. “Recognition and Completeness: Two Key Metrics for Judging the Utility of Citizen Science Data.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 21 (4): 167–74.