Introduction

Florida is the global epicenter for nonnative herpetofaunal (i.e., reptiles and amphibians) introductions due to the intentional and unintentional actions of people (Fujisaki et al. 2015). Although most of these introductions are reptiles, approximately 20 species of nonnative amphibians (frogs, salamanders, caecilians) have been documented in the state (Krysko et al. 2016), with numerous additional species recorded in other US states, especially Hawaii and California (Kraus 2009; Meshaka et al. 2022). Historically, nonnative amphibians arrived in Florida unintentionally, often as stowaways in shipments of cargo. For example, the Cuban treefrog initially made it to the United States via Florida in the early 1900s as a stowaway in cargo shipped to Key West (see Johnson 2007). However, since the early 2000s, the pet trade has been responsible for the introduction of most of these nonnative amphibians (Kraus 2009; Krysko et al. 2016).

Most amphibian introductions have not resulted in the establishment of breeding populations, but of those species that successfully establish, some thrive and expand, eventually becoming invasive. We define an invasive species of amphibian as one that a) is not native to a specific geographic area, b) was introduced by the intentional or unintentional actions of humans, and c) does or can cause harm to the environment, economy, or human quality of life (Iannone et al. 2020). For example, cane toads are native to Central and South America but were intentionally introduced to Australia in a failed attempt to control insect pests of sugar cane (Easteal 1981). The toads became established, spread across much of tropical Australia, and due to poisons produced in their skin have had substantial negative impacts on native wildlife (Shine 2010). They are also responsible for toxic poisoning of pet dogs and cats (Eubig 2001).

This publication summarizes general knowledge about the greenhouse frog, a species introduced and established in the United States. Our target audience is primarily homeowners in Florida and Hawaii where the greenhouse frog is most common, but residents in other southeastern states will also find this publication useful. Greenhouse frogs have been documented in several other states in this region and continue to expand their range (Rödder and Lötters 2010). Homeowners usually encounter greenhouse frogs in their gardens and among potted plants, and sometimes when the frogs fall into their swimming pools. People are often curious and seek information on the frog’s identity. Our goals are 1) to provide tips on greenhouse frog identification, 2) to show the frog’s geographic range in the United States, and 3) to describe its biology and known or potential impacts.

Greenhouse Frog Background

The greenhouse frog (aka Cuban flat-headed frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris) is one of more than 150 species in the scientific genus Eleutherodactylus native to the West Indies (Hedges et al. 2008). E. planirostris is native to the Bahamas, Cayman Islands, and Cuba. In its native range, it is found in a variety of natural and human-modified habitats (Henderson and Powell 2009). In addition to being introduced to the United States, greenhouse frogs have also been documented in Mexico, on several islands in the Caribbean, and as far away as the Philippines and the US territory of Guam (Kraus 2009; Beard et al. 2017). Based on genetic data, some scientists suggest that greenhouse frogs may actually be native to Florida (Heinicke et al. 2011), and fossils belonging to frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylus have recently been described from Florida (Vallejo-Pareja et al. 2024). Nonetheless, in this publication, we consider greenhouse frogs to be an introduced species in Florida, and they have unequivocally been introduced by people to other states in the recent past.

Greenhouse frogs were the first introduced amphibian documented in the United States and were reported from Florida in 1863 (Cope 1863). By the early 1940s, they were documented in isolated populations across the peninsula (Goin 1947). They have since expanded their range in Florida and appear to have colonized much of the state in the last 25 years (Mularo et al. 2023). They have also recently become established in several other states in the Southeast—since the 1990s, greenhouse frogs have established populations in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas (Davis 2021; Dodd 2023). Since around 2020, there have been numerous reports of greenhouse frogs from states beyond the Southeast (iNaturalist.org). Greenhouse frogs are inadvertently transported to new places as stowaways in ornamental plants (Kraus 1999). Because they are small and inconspicuous and like to hide under cover in moist environments, they are easily overlooked. Additionally, as described below, they lay eggs terrestrially, so an entire clutch (e.g., group of eggs) of fertile eggs may hitch a ride in a plant shipped across the country.

Identifying Greenhouse Frogs

Adult greenhouse frogs are small, rarely exceeding 2.5 cm (1 in.) in length, with males being smaller than females (Meshaka et al. 2004; Olson and Beard 2012). They are reddish-brown with numerous small dark spots and flecks. Their rear legs have light and dark bands. There is a light brown, triangular mark on the head between their bronze-colored eyes and their snout. They have numerous small warts on their legs and back, giving the frogs a somewhat rough appearance (Figures 1 and 2). The ends of their thin toes are slightly expanded, and their upper lip usually has several small, white spots. There are two distinct phases or morphs—a mottled morph and a striped morph. Striped individuals have two tan stripes on their back running from their eyes to their groin (Figure 3). The ratio of striped to mottled individuals varies among locations (Goin 1947; Dodd 2023).

Credit: Dr. Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS

Credit: Dustin Smith, North Carolina Zoo

Credit: Brad “Bones” Glorioso, US Geological Survey

Greenhouse frogs are ground-dwelling and most often occur in leaf litter (Hedges et al. 2008). Although they are usually found in moist or damp conditions, they are not aquatic and do not have webbed toes. They can climb on rough surfaces (Figures 4 and 5), but they lack the enlarged toepads typical of treefrogs and are never found clinging to glass windows. To some, greenhouse frogs may resemble small toads. However, greenhouse frogs are slenderer and have a more pointed snout than toads found in the United States. Greenhouse frogs are active throughout the year but are most active on warm, damp nights and on rainy and/or cloudy days (Goin 1947; Dodd 2023). Human-supplied sources of water, from watering lawns and gardens, for instance, can also elicit daytime activity (Goin 1947).

Credit: Dr. Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jamm Hostetler

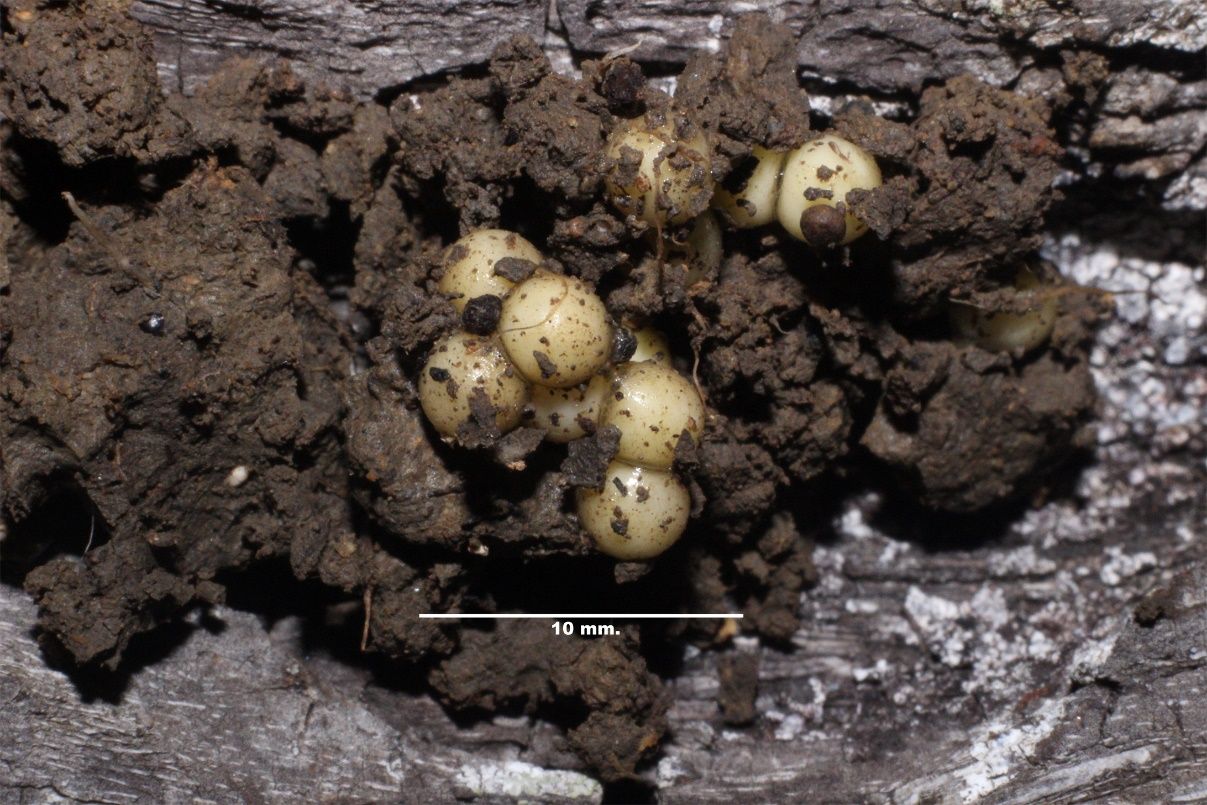

Greenhouse frog eggs are round, gelatinous, clear, and laid in small clusters in a moist, protected area (Figure 6). The eggs are small, about the size of a pea. This species lacks a tadpole stage; froglets emerge from the eggs fully formed (Goin 1947). Recently hatched greenhouse frogs are tiny (Figure 7). Once they grow a bit larger, they resemble adults in color and pattern (Figure 8).

Credit: Dustin Smith, North Carolina Zoo

Credit: Dustin Smith, North Carolina Zoo

Credit: Dr. Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS

Although greenhouse frogs are not likely to be confused with native frogs across much of their range in the southeastern United States, they do look very similar to the native Rio Grande chirping frog (Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides). Like the greenhouse frog, the Rio Grande chirping frog is a small brown frog with thin toes and a somewhat rough appearance of the skin on its back. However, unlike greenhouse frogs, Rio Grande chirping frogs have a dark bar on each side of their head from their eye to their snout. They also usually have dark spots on their back (though this feature is variable and not present in every frog; see Figure 9. Greenhouse frogs lack these spots. Both species may be found around human dwellings, and their range overlaps somewhat in east Texas and Louisiana (Dodd 2023). Rio Grande chirping frogs are expanding their range east towards the Florida Panhandle as greenhouse frogs continue to spread west into Texas, so care should be taken not to misidentify one as the other.

Credit: Tom Lott

Greenhouse Frog Biology—Distribution and Habitats

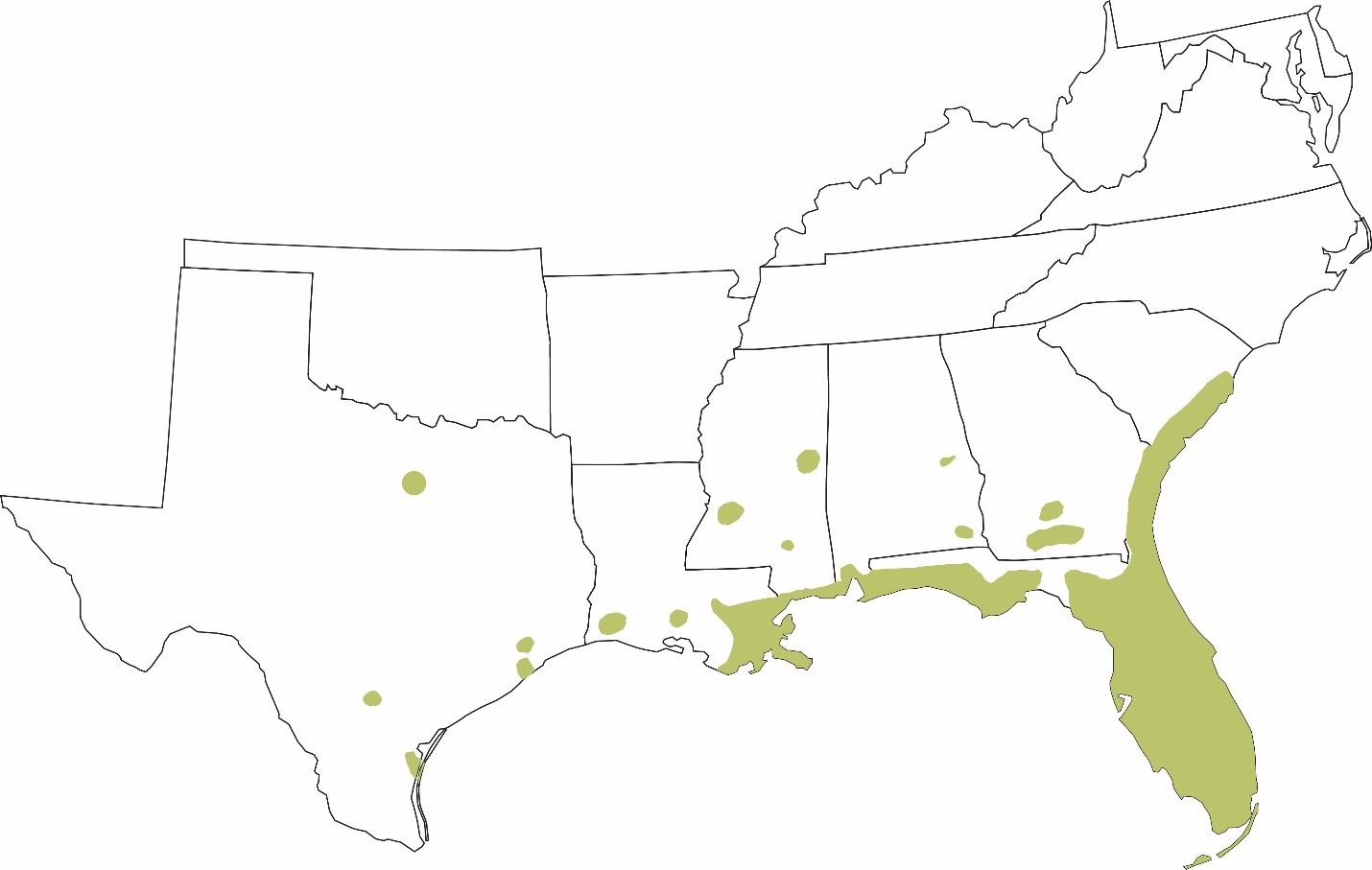

Greenhouse frogs are established in several states across the southeastern United States, including much of Florida and parts of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas (Figure 10). They are also established in the Hawaiian Islands (see below).

Credit: Tracy Bryant, UF/IFAS

In the United States, greenhouse frogs have become established in areas where the annual average temperature and rainfall in the wettest month of the year are similar to those in the frog’s native range (Bomford et al. 2009; Rödder and Lötters 2010). However, greenhouse frogs can also be found in parts of the southeastern United States with relatively cold daily minimum temperatures of 4°C–8°C (~40°F–45°F, Tuberville et al. 2005; Olson 2011).

Greenhouse frogs are found in a wide variety of habitats in their native range in the Caribbean, including in wet and dry forests, mountainous regions, coastal and riverine areas, rocky outcrops, and caves, as well as around human settlements in gardens and plant nurseries (Garrido and Schwartz 1968; Díaz and Cádiz 2008; Henderson and Powell 2009; Olson 2011). In the southeastern United States, greenhouse frogs are commonly found in natural areas including pine forests, open grasslands, and wet and dry hardwood forests. They are common in debris piles and ornamental plant gardens in urban landscapes (Enge 1997; Meshaka et al. 2004; Olson 2011). Greenhouse frogs frequently fall into swimming pools. It is common to find them floating at the surface or collecting in pool skimmers (Figure 11).

Credit: Dr. Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS

Greenhouse frogs in Florida have frequently been observed burrowing into moist soil, leading some authors to describe them as semi-fossorial (Goin 1947; Meshaka et al. 2004). They are also found underneath rocks, logs, leaf litter, potted plants, and other cover objects (Goin 1947; Schwartz and Henderson 1991), as well as in bromeliads (Neill 1951) and compost bins. Greenhouse frogs also frequent the burrows of gopher tortoises in dry, sandy habitats (Lips 1991; Witz and Wilson 1991).

Greenhouse frogs have become established on five Hawaiian Islands: Hawaiʻi, Kauaʻi, Lānaʻi, Maui, and Oʻahu (Kraus et al. 1999). It is likely that they were originally introduced to Hawaii through imported nursery plants, likely shipped from Florida (Kraus et al. 1999). Most greenhouse frog populations in Hawaii occur in lowland areas (0–500 meters), although some frogs have been detected at elevations of up to 1,115 meters (Olson 2011). As in the continental United States, greenhouse frogs in Hawaii have been found in a wide variety of habitat types including orchards, plant nurseries, gardens, pastures, parks, forests, and roadsides, and around human development (Olson 2011).

Greenhouse Frog Biology—Diet

Greenhouse frogs eat small invertebrates they find in leaf litter. Their diet includes mites, springtails, amphipods, isopods, roaches, spiders, beetles, millipedes, and ants (Dodd 2023). Studies in Florida and Hawaii found that ants are most preferred and make up 30%–40% of a greenhouse frog’s diet (Goin 1947; Olson and Beard 2012). In their native range of Cuba, greenhouse frogs also feed predominantly on ants (García-Padrón and Quevedo 2022). Ants also dominate the diet of greenhouse frogs introduced to Jamaica (Stewart 1977).

Greenhouse Frog Biology—Predators

Because they are small, ground-dwelling frogs, greenhouse frogs are potentially prey for many species of wildlife. In their native range, racer snakes of the genus Cubophis are known predators of greenhouse frogs (Henderson and Powell 2009). Known predators in the United States include the small snakes Rhadinaea flavilata (pine woods snake) (Durso and Smith 2017), and Diadophis punctatus (ring-necked snake) (Meshaka 2011). It is highly likely that black racers (Coluber constrictor), common garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis), and other frog-eating snakes also prey on greenhouse frogs in the United States. Cuban treefrogs (Osteopilus septentrionalis) have been reported to eat greenhouse frogs (Meshaka 1996), as have southern leopard frogs (Baakliny and Kustok 2023). It is likely that birds of the Southeast that feed in leaf litter, such as Carolina Wrens and Brown Thrashers also occasionally eat greenhouse frogs. Woodpeckers and owls are documented predators of greenhouse frogs in Cuba (Alonso and Rodriguez 2003; Rodriguez-Cabrera et al. 2020). Nonetheless, there is a lack of research documenting specific predators of greenhouse frogs in the United States.

Greenhouse Frog Biology—Reproduction

Greenhouse frogs are active at all times of the year, given suitable weather conditions (Meshaka and Layne 2005). In the Caribbean, breeding occurs from April–October during the wet season (Iturriaga et al. 2014). In Florida, the breeding season of greenhouse frogs is May–September, but in the southern part of the peninsula they breed from late February through mid-November (Goin 1947; Wright and Wright 1949; Meshaka et al. 2004).

As noted above, greenhouse frogs are direct developers—there is no free-living tadpole stage—and tiny froglets emerge from eggs laid terrestrially (Goin 1947). Greenhouse frogs commonly deposit their eggs in leaf litter, flower beds, and flowerpots, but any place with moist soil and cover may be used as a nesting place (Goin 1947; Hodl 1990). Eggs (3–6 mm in diameter) are laid in small clumps (Figures 6 and 12) and the number of eggs varies from 3–26 (Goin 1947). Females have been observed to lay their eggs in several layers in a shallow hole and kick dirt on top to hide them (Goin 1947), but they will also attach them to man-made cover objects. The eggs are usually abandoned to develop without any care from the male or female (Goin 1947; Dodd 2023), but a suspected case of parental care was reported from Cuba (Iturriaga and Dugo-Cota 2018). In Florida, greenhouse frog eggs take 13–20 days to hatch, averaging 15–16 days (Goin 1947). Most eggs in a clutch hatch on the same day, but it is common for a few to hatch a day earlier and a few a day later than the rest (Goin 1947). Hatchlings mature in about a year (Goin 1947).

Credit: Andres Camilo Montes Correa, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi

As with most frogs, male greenhouse frogs call to attract females for mating, although courtship behavior in the species has yet to be described by scientists (Dodd 2023). However, unlike the loud calls of most native frogs in the United States, the calls of greenhouse frogs are faint and easily missed or mistaken for the sounds of an insect. Various authors have described the call of a greenhouse frog as a soft twittering and chirping with a series of 4–6 notes repeated multiple times (Goin 1947; Meshaka et al. 2004). One of the authors of this publication (SAJ) once had a colleague describe the call of a greenhouse frog as sounding like the squeak of very small sneakers on the hardwood of a tiny basketball court. Males call from sunset through dawn and into early morning, with peaks of activity shortly after dusk and dawn (Goin 1947).

Impacts of Greenhouse Frogs

As defined earlier, an invasive species may harm the ecology, economy, or quality of human life within its introduced range (Iannone et al. 2020). While several species of frogs introduced in the United States (e.g., American bullfrog, Cuban treefrog, cane toad) certainly meet the criteria to be considered invasive, the greenhouse frog’s case is not as clear. Biologists do occasionally refer to greenhouse frogs in Florida as “invasive” in scientific journal articles (Rödder and Lotters 2010; Heinicke at al. 2011; Mularo et al. 2023). However, species accounts of greenhouse frogs in field guides and journal articles often mention a lack of negative environmental impacts, with some even suggesting that greenhouse frogs benefit the environment by serving as prey for native species (Dorcas and Gibbons 2008; Jensen et al. 2008; Krysko et al. 2019). Below, we summarize known and potential ecological, economic, and human-quality-of-life impacts of introduced greenhouse frogs in the United States.

Ecological Impacts

The environmental effects of the greenhouse frog are poorly studied in the continental United States, but obvious negative ecological effects have yet to be documented. There is potential for greenhouse frogs to compete with native species, including several native skinks that forage on the ground and feed on small arthropods. Greenhouse frogs may also compete for food with the native eastern narrow-mouth frog (Gastrophryne carolinensis), which like the greenhouse frog, feeds heavily on ants. Further research is required before any definitive statements can be made in either direction.

In Hawaii, where the ecology of introduced greenhouse frogs has been better documented, scientists have suggested potential negative ecological impacts there and elsewhere in the Pacific. One study carried out on the island of Hawaii found that greenhouse frogs eat up to 129,000 invertebrates per hectare (2.47 acres) in a single night (Olson and Beard 2012). The percentage of native invertebrates among the diet of the sampled frogs was not determined, but it likely included numerous native species. On the other hand, the study was able to determine that the frogs ate numerous introduced species of invertebrates—32% of the diet was ants, and there are no ants native to Hawaii (Olson and Beard 2012). Moreover, the introduced greenhouse frog may actually be indirectly beneficial because several species of ants eaten by greenhouse frogs are predators of native Hawaiian invertebrates (Olson et al. 2012). Although evidence is lacking, there is potential for greenhouse frogs to compete with native insect-eating species in Hawaii and possibly affect ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling (Kraus et al. 1999; Kraus 2009; Olson et al. 2012). Additionally, scientists have speculated that if brown treesnakes (a major invasive species on Guam) invade Hawaii, the abundant greenhouse frogs there may facilitate their success by serving as an additional food source (Mathies et al. 2012).

Another potential impact of greenhouse frogs relates to their role as a vector of emerging amphibian pathogens. Pathogens such as Ranavirus (Rv) and the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) have led to widespread amphibian declines (Daszak et al. 2003; Fisher et al. 2009; Price et al. 2014). Bd has been documented in greenhouse frogs in Florida (Rizkalla 2010), Georgia (Rivera et al. 2019), and Hawaii (Goodman et al. 2019). Further, one study found that greenhouse frogs in Georgia had a higher prevalence and intensity of Rv than did three native frog species that were also sampled (Rivera et al. 2019). These findings suggest that greenhouse frogs may spread or amplify amphibian pathogens and could potentially contribute to disease outbreaks in native amphibians.

Economic Impacts

The coqui frog (Eleutherodactylus coqui), a close relative of the greenhouse frog that has also been introduced to Hawaii, has well-documented negative economic impacts. The loud mating calls of the males make real estate with nearby or dense coqui populations less desirable, resulting in a reduction of home values (Kaiser and Burnett 2006). Additionally, efforts to manage coqui populations and prevent their spread have proven both costly and ineffective (Beard et al. 2017). As described above, greenhouse frogs have a faint call that most people do not find offensive, and therefore are not generally considered to be a nuisance. However, in part due to the impacts of the coqui, all frogs are listed as State Injurious Species in the Hawaiian Islands (no frogs are native there). As a result, international and interisland transport of ornamental plants requires shippers of plants to spend money on efforts to ensure their shipments are free of greenhouse and coqui frogs and their eggs (Olson et al. 2012). There are no such laws in the continental United States—negative economic impacts there have not been documented and are likely negligible.

Impacts on Human Quality of Life

Greenhouse frogs pose no direct threats to people or pets, unlike the cane toad, which is toxic and potentially lethal to domestic dogs and cats (see the Ask IFAS publication The Cane or “Bufo Toad [Rhinella marina] in Florida). As noted above, the calls of greenhouse frogs are quiet, and therefore not likely to be a nuisance to people. They do frequently fall into swimming pools and must be removed during pool maintenance, which some homeowners likely consider an inconvenience. Occasionally a greenhouse frog might find its way into a home or building, which some people may find annoying, but by and large these small frogs do not currently have direct or widespread negative impacts on human quality of life.

In Hawaii, however, greenhouse frogs have been identified as intermediate hosts of the rat lungworm (Niebuhr et al. 2020). Rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) has not yet been documented in greenhouse frogs from Florida, but this parasite is present in Florida (Walden et al. 2021) and has been confirmed in Cuban treefrogs from Florida (Chase et al. 2022), an invasive frog species in Florida and elsewhere in the Southeast (see The Cuban Treefrog [Osteopilus septentrionalis] in Florida).

Rat lungworm is an internal parasite that affects the brain, spinal cord, and nerves of infected animals. Rats are usually the definitive (final) host in the life cycle of the parasite, and the lungworm can reproduce in rats (Cowie 2013). Intermediate hosts, most often snails, become infected when they eat rat feces containing lungworm eggs (Cowie 2013). When a rat eats an infected snail, the life cycle of the worm is perpetuated (Cowie 2013). However, other animals may also eat infected snails or rats, become infected with Angiostrongylus lungworms, and develop rat lungworm disease (angiostrongylosis). These include domestic dogs (Lee et al. 2021; Morgan et al. 2021). Despite this, angiostrongylosis is not presently considered to be a common disease of domestic dogs in the places where it has been studied (Lee et al. 2021), but it is a serious disease in an infected dog. Although the threat of a pet dog contracting the disease from consuming a greenhouse frog in the United States appears minimal, pet owners still should become educated about rat lungworm disease.

People do not need to worry about contracting angiostrongylosis from greenhouse frogs (or Cuban treefrogs). A human would have to eat an infected frog to become infected with rat lungworm (Morgan et al. 2021). Handling or touching an infected frog poses no risk to people.

How you can help!

Negative ecological outcomes in the United States presently appear to be minimal, but much research remains to be conducted to better explore the potential impacts of greenhouse frogs on native species and ecosystems. Impacts on the economy and human quality of life caused by greenhouse frogs are also of little concern in the continental United States at present. We do not recommend that people try to capture and euthanize this introduced species in the United States. However, we do encourage people to report observations of greenhouse frogs so scientists can monitor their spread.

Report greenhouse frog observations

Please report observations of greenhouse frogs at the crowdsourced platform iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/). Observations must be supported with quality digital images. For more information about how to find and report observations of frogs and other amphibians and reptiles, check out “Herping Adventures: A Guide to Exploring and Documenting Reptiles and Amphibians with iNaturalist” available through Ask IFAS.

Additional Information

UF/IFAS Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation: Florida’s Frogs

U.S. Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species

Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk (HEAR.org) Alien Caribbean Frogs in Hawaii

References

Alonso [Bosch], R., and A. Rodríguez. 2003. “Entre la hojarasca bajo nuestros pies.” In Anfibios y Reptiles de Cuba, edited by L. Rodríguez Schettino, pp. 30–37. Vaasa, Finland: UPC Print.

Baakliny, J., and N. J. Kustok. 2023. “Lithobates sphenocephalus (Southern Leopard Frog). Diet.” Herpetological Review 54:272.

Beard, K. H., S. A. Johnson, and A. B. Shields. 2017. “Frogs (Coqui frogs, Greenhouse frogs, Cuban tree frogs, and Cane toads).” In Ecology and Management of Terrestrial Vertebrate Invasive Species in the United States, edited by W. C. Pitt, J. C. Beasly, and G. W. Witmer, pp. 163–191. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 403 pp. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315157078-9

Bomford, M., F. Kraus, S. C. Barry, and E. Lawrence. 2009. “Predicting Establishment Success for Alien Reptiles and Amphibians: A Role for Climate Matching.” Biological Invasions 11:713–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-008-9285-3

Chase, E. C., R. J. Ossiboff, T. M. Farrell, A. L Childress, K. Lykins, S. A. Johnson, N. Thompson, and H. D. S. Walden. 2022. “Rat Lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) in the Invasive Cuban Treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) in Central Florida.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 58:454–456. https://doi.org/10.7589/JWD-D-21-00140

Cope, E. D. 1863. "On Trachycephalus, Scaphiopus, and other American Batrachia." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 15:43–54.

Cowie, R. H. 2013. “Biology, Systematics, Life Cycle, and Distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the Cause of Rat Lungworm Disease.” Hawai'i Journal of Medicine & Public Health 72 (6 Suppl 2): 6.

Daszak, P., A. A. Cunningham, and A. D. Hyatt. 2003. “Infectious Disease and Amphibian Population Declines.” Diversity and Distributions 9:141–150. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-4642.2003.00016.x

Davis, D. R. 2021. “New Distributional Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from the Western Gulf Coastal Plain of Texas, USA.” Herpetological Review 52:807–809.

Díaz, L. M., and A. Cádiz. 2008. Guía taxonómica de los anfibios de Cuba. – ABC Taxa, 4:1–294.

Dodd, C. K. 2023. Frogs of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. https://doi.org/10.56021/9781421444925

Dorcas, M. E., and J. W. Gibbons. 2008. Frogs & Toads of the Southeast. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

Durso, A. M., and L. Smith. 2017. “Eleutherodactylus planirostris (Greenhouse Frog). Predation.” Herpetological Review 48:606.

Easteal, S. 1981. “The History of the Introductions of Bufo marinus (Amphibia: Anura); a Natural Experiment in Evolution.” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 16:93–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1981.tb01645.x

Enge, K. M. 1997. “A Standardized Protocol for Drift-Fence Surveys.” Technical Report No. 14, Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, Tallahassee.

Fisher, M. C., T. W. Garner, and S. F. Walker. 2009. “Global Emergence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Amphibian Chytridiomycosis in Space, Time, and Host.” Annual Review of Microbiology 63:291–310. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073435

Eubig, P. A. 2001. “Bufo Species Toxicosis: Big Toad, Big Problem.” Veterinary Medicine 96:594–599.

Fujisaki, I., F. J. Mazzotti, J. Watling, K. L. Krysko, and Y. Escribano. 2015. “Geographic risk assessment reveals spatial variation in invasive species potential of exotic reptiles in invasive species hotspot.” Herpetological Conservation and Biology 10:621–632.

García-Padrón, L. Y., and C. A. B. Quevedo. 2022. “Notes on the Diet of the Cuban Flat-Headed Frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris (Eleutherodactylidae) from Two Understudied Habitats in Western Cuba.” Reptiles & Amphibians 29: 311–313. https://doi.org/10.17161/randa.v29i1.17956

Garrido, O. H., and A. Schwartz. 1968. Anfibios, reptiles y aves de la peninsula de Guanahacabibes, Cuba. Poeyana, ser. A 53:1–68.

Goin, C. J. 1947. “Studies on the Life History of Eleutherodactylus ricordii planirostris (Cope) in Florida.” University of Florida Studies, Biological Science Series 4:1–66.

Goodman, R. M., J. A. Tyler, D. M. Reinartz, and A. N. Wright. 2019. “Survey of Ranavirus and Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Introduced Frogs in Hawaii, USA.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 55: 668–672. https://doi.org/10.7589/2018-05-137

Hedges, S. B., W. E. Duellman, and M. P. Heinicke. 2008. “New World Direct-Developing Frogs (Anura: Terrarana): Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, Biogeography, and Conservation.” Zootaxa 1737:1–182. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1737.1.1

Heinicke, M. P., L. M. Diaz, and S. B. Hedges. 2011. “Origin of Invasive Florida Frogs Traced to Cuba.” Biology Letters 7:407–410. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2010.1131

Henderson, R. W., and R. Powell. 2009. “Natural History of West Indian Reptiles and Amphibians.” Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Hodl, W. 1990. “Reproductive Diversity in Amazonian Lowland Frogs.” Fortschritte der Zoologie 38:41–60.

Iannone, B.V., III, S. Carnevale, M. B. Main, J. E. Hill, J. B. McConnell, S. A. Johnson, S.F. Enloe, et al. 2020. “Invasive Species Terminology: Standardizing for Stakeholder Education.” Journal of Extension 58:3. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.58.03.27

Iturriaga, M., A. Sanz, and R. Oliva. 2014. “Seasonal Reproduction of the Greenhouse Frog Eleutherodactylus planirostris (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) in Havana, Cuba.” South American Journal of Herpetology 9:142–150. https://doi.org/10.2994/SAJH-D-13-00039.1

Iturriaga, M., and A. Dugo-Cota. 2018. “Parental Care in the Greenhouse Frog Eleutherodactylus planirostris (Cope, 1862) from Cuba.” Herpetology Notes 11:857–861.

Jensen, J. B., C. D. Camp, G. W. Gibbons, and M. J. Elliott. 2008. Amphibians and Reptiles of Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Johnson, S. A. 2023. “The Cuban Treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) in Florida: WEC218/UW259, 2/2023.” EDIS 2023 (1). Gainesville, Florida. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-UW259-2023

Kaiser, B. A., and K. M. Burnett. 2006. “Economic Impacts of Coqui Frogs in Hawaii.” Interdisciplinary Environmental Review 8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1504/IER.2006.053951

King, W., and T. Krakauer. 1966. “The Exotic Herpetofauna of Southeast Florida.” Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 29:144–154.

Kraus, F., E. W. Campbell, A. Allison, and T. Pratt. 1999. “Eleutherodactylus Frog Introductions to Hawaii.” Herpetological Review 30:21–25.

Kraus, F. 2009. Alien Reptiles and Amphibians: A Scientific Compendium and Analysis. Springer. 563 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8946-6

Krysko, K. L., K. M. Enge, and P. E. Moler. 2019. Amphibians and Reptiles of Florida. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. 706 pp.

Krysko, K. L., L. A. Somma, D. C. Smith, C. R. Gillette, D. Cueva, J. A. Wasilewski, K. M. Enge, et al. 2016. “New Verified Nonindigenous Amphibians and Reptiles in Florida through 2015, with Summary of over 152 Years of Introductions.” IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians 23:110–143. https://doi.org/10.17161/randa.v23i2.14119

Lee, R., T. Y. Pai, R. Churcher, S. Davies, J. Braddock, M. Linton, J. Yu, et al. 2021. “Further Studies of Neuroangiostrongyliasis (Rat Lungworm Disease) in Australian Dogs: 92 New Cases (2010–2020) and Results for a Novel, High Sensitivity qPCR Assay.” Parasitology 148:178–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182020001572

Lips, K. R. 1991. “Vertebrates Associated with Tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) Burrows in Four Habitats in South-Central Florida.” Journal of Herpetology 25:477–481. https://doi.org/10.2307/1564772

Mathies, T., W. C. Pitt, and J. A. Rabon. 2012. “Boiga irregularis (Brown Treesnake) Diet.” Herpetological Review 43:143–144.

Meshaka, W. E., Jr. 1996. “Diet and Colonization of Buildings by the Cuban Treefrog, Osteopilus septentrionalis (Anura: Hylidae).” Caribbean Journal of Science 32:59–63.

Meshaka, W. E., Jr., B. P. Butterfield, and J. B. Hague. 2004. The Exotic Amphibians and Reptiles of Florida. Malabar, Florida: Kreiger Publishing Company.

Meshaka, W. E., Jr. 2011. “A Runaway Train in the Making: The Exotic Amphibians, Reptiles, Turtles, and Crocodilians of Florida.” Herpetological Conservation & Biology 6 (Monograph 1):1–101.

Meshaka, W. E., Jr., S. L. Collins, R. B. Bury, and M. L. McCallum. 2022. Exotic Amphibians and Reptiles of the United States. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813066967.001.0001

Meshaka, W. E., and J. N. Layne 2005. “Habitat Relationships and Seasonal Activity of the Greenhouse Frog (Eleutherodactylus planirostris) in Southern Florida.” Florida Scientist 68:35–43.

Morgan, E. R., D. Modry, C. Paredes-Esquivel, P. Foronda, and D. Traversa. 2021. “Angiostrongylosis in Animals and Humans in Europe.” Pathogens 10:1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10101236

Mularo, A. J., J. A. DeWoody, and X. E. Bernal. 2023. “Establishment and Occurrence History of Three Invasive Anuran Species Across the Florida Peninsula.” Journal of Herpetology 57:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1670/23-002

Niebuhr, C. N., S. I. Jarvi, L. Kaluna, B. L. Torres Fischer, A. R. Deane, I. L. Lenbach, and S. R. Siers. 2020. “Occurrence of Rat Lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) in Invasive Coqui Frogs (Eleutherodactylus coqui) and Other Hosts in Hawaii, USA.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 56:203–207. https://doi.org/10.7589/2018-12-294

Neill, W. T. 1951. “A Bromeliad Herpetofauna in Florida.” Ecology 32:140–143. https://doi.org/10.2307/1930979

Olson, C. A. 2011. “Diet, Density, and Distribution of the Introduced Greenhouse Frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris, on the Island of Hawaii.” M.S. thesis. Utah State University, Logan.

Olson, C. A., and K. H. Beard. 2012. “Diet of the Introduced Greenhouse Frog in Hawaii. Copeia 2012:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1643/CE-11-008

Olson, C. A., K. H. Beard, and W. C. Pitt. 2012. “Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species.” 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae).” Pacific Science 66:255–270. https://doi.org/10.2984/66.3.1

Price, S. J., T. W. Garner, R. A. Nichols, F. Balloux, C. Ayres, A. M. C. de Alba, and J. Bosch. 2014. “Collapse of Amphibian Communities Due to an Introduced Ranavirus.” Current Biology 24:2586–2591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.028

Rivera, B., K. Cook, K. Andrews, M. S. Atkinson, and A. E. Savage. 2019. “Pathogen Dynamics in an Invasive Frog Compared to Native Species.” EcoHealth 16:222–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-019-01432-4

Rizkalla, C. E. 2010. “Increasing Detections of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Central Florida, USA.” Herpetological Review 41:180.

Rödder, D., and S. Lötters. 2010. “Explanative Power of Variables Used in Species Distribution Modelling: An Issue of General Model Transferability or Niche Shift in the Invasive Greenhouse Frog (Eleutherodactylus planirostris).” Naturwissenschaften 97:781–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-010-0694-7

Rodríguez-Cabrera, T. M., L. Y. García-Padrón, E. M. Savall, and J. Torres. 2020. “Predation on Direct-Developing Frogs (Eleutherodactylidae: Eleutherodactylus) in Cuba: New Cases and a Review.” Reptiles & Amphibians 27:161–168. https://doi.org/10.17161/randa.v27i2.14175

Schwartz, A., and R. W. Henderson. 1991. Amphibians and Reptiles of the West Indies: Descriptions, Distributions, and Natural History. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press.

Shine, R. 2010. “The Ecological Impact of Invasive Cane Toads (Bufo marinus) in Australia.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 85 (3): 253–291. https://doi.org/10.1086/655116

Stewart, M. M. 1977. “The Role of Introduced Species in a Jamaican Frog Community.” Actas del IV Simposium Internacional de Ecologia Tropical, Tomo 1:111–146.

Tuberville, T. D., J. D. Willson, M. E. Dorcas, and J. W. Gibbons. 2005. “Herpetofaunal Species Richness of Southeastern National Parks.” Southeastern Naturalist 4:537–569. https://doi.org/10.1656/1528-7092(2005)004[0537:HSROSN]2.0.CO;2

Vallejo-Pareja, M. C., E. L. Stanley, J. I. Bloch, and D. C. Blackburn. 2024. “Fossil frogs (Eleutherodactylidae: Eleutherodactylus) from Florida suggest overwater dispersal from the Caribbean by the late Oligocene.” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 201:431–446. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad130

Walden, H. D. S., J. Slapcinsky, J. Rosenberg, and J. F. X. Wellehan. 2021. “Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Rat Lungworm) in Florida, U.S.A.: Current Status.” Parasitology 148:149.152. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182020001286

Witz, D. W., and D. S. Wilson. 1991. “Distribution of Gopherus polyphemus and Its Vertebrate Symbionts in Three Burrow Categories.” American Midland Naturalist 126:152–158. https://doi.org/10.2307/2426159

Wright, A. A., and A. H. Wright. 1949. Handbook of Frogs and Toads. Ithaca, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates. 640 pp.