This publication is intended for teachers or students interested in teaching or learning ecological concepts using camera traps.

Introduction

Direct observation is a powerful tool for promoting learning across a wide spectrum of disciplines, including ecology. Camera trapping is a well-known method of directly observing wildlife species. When set up creatively, camera trapping can be used by educators to answer questions related to numerous ecological concepts, such as wildlife habitat use and food selection. In this article, we provide some examples of effectively using camera traps to teach ecological concepts related to wildlife feeding preferences, daily activity, human disturbance, ecosystem engineering, and pollinators. In addition, we will discuss using iNaturalist, an online social network used to share observations of nature, as a tool to gather additional information on wildlife species. These methods can be used to educate general audiences such as students, hunters, and landowners.

General Settings

Setting up camera traps for an observation or experiment, even in the classroom environment, varies widely depending on the question of interest. Cameras can be placed on a tree, fence post, tripod, or stake, and be set for either picture or video recording. Video recordings are often better at capturing individual animal behaviors. However, video mode drains batteries faster, and reviewing footage is more time-consuming than reviewing photos. If available, camera traps with time-lapse features are useful for capturing images of smaller wildlife species (e.g., reptiles and amphibians). Always obtain permission to set cameras before placing them on properties that do not belong to you. If cameras are placed in visible areas subject to public traffic, securing them with a cable lock can be a prudent step. For more specific information on camera trap settings and considerations, refer to Ask IFAS publication WEC472, “Camera Trapping for Wildlife” (McDonald et al. 2025).

Credit: Cat Wofford, UF/IFAS

Wildlife Daily Activity

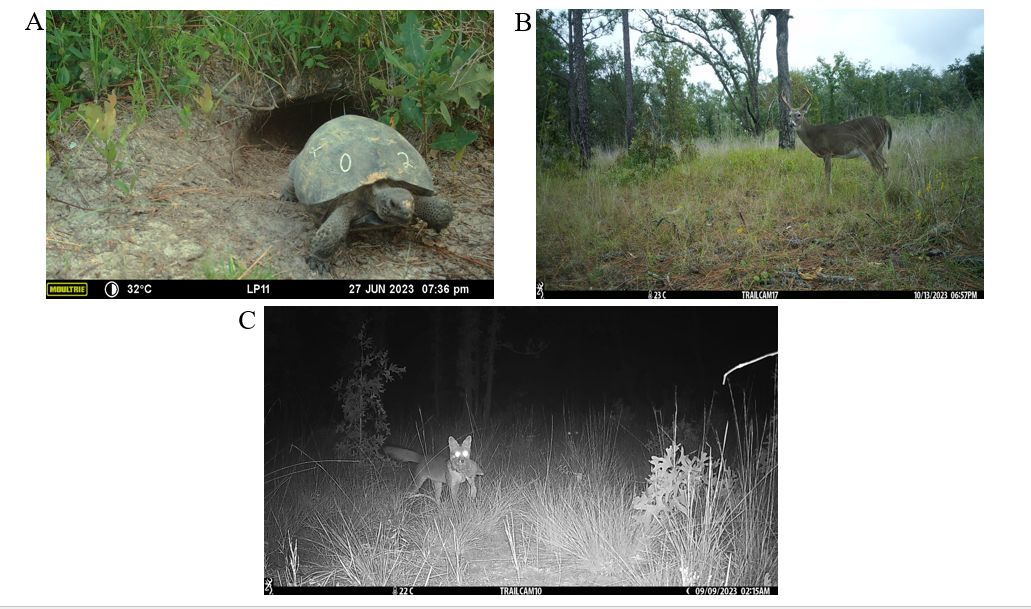

Daily activity patterns vary depending on wildlife species; camera traps can help detect these patterns. Species are typically categorized as either diurnal, crepuscular, or nocturnal based on their activity patterns (Figure 2). Diurnal species are active during the day, crepuscular species are most active during twilight hours (just before sunrise and just after sunset), and nocturnal species are active during the night. Camera traps provide a useful means to understand these dynamics by recording wildlife activity over time.

Credit: A) Tall Timbers Research Station and UF/IFAS Wildlife Ecology and Land Management Lab. B) and C) Kathleen Carey, UF/IFAS Wildlife Ecology and Land Management Lab.

Common diurnal species found in Florida include eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus), and bird species such as wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) and blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata). Common species that are primarily crepuscular are white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus). There are various native nocturnal species in Florida, such as the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), raccoon (Procyon lotor), and bobcat (Lynx rufus). Camera traps show students and other interested groups when species are active by providing a time stamp on each image and displaying these patterns over time. If students are struggling to identify species, the time stamp can provide useful insights into which species are common during that time of day. It is important to consider activity patterns of your species of interest and adjust the camera settings accordingly. As an example, for observations of diurnal species, cameras can be set to record pictures or videos during the day and to shut off at night in order to preserve battery life. As a group, you can investigate questions like the ones below.

- When is a particular species most active?

- Is there a specific season when certain species are most active?

- In which habitat does a species exhibit the most activity?

Feeding Preferences

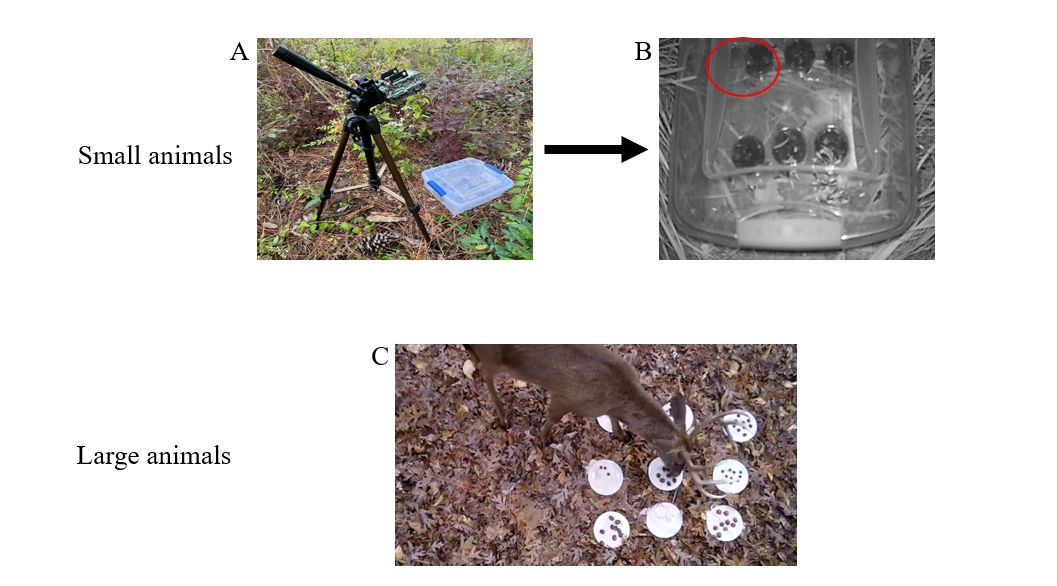

Studies on food preferences can teach students the difference between carnivores, omnivores, and herbivores. They can also provide a better understanding of species’ food preferences and roles within the food web (e.g., seed dispersal). One method of using camera traps to teach ecological concepts is by monitoring food items and observing food preferences among species (Figure 3).

Credit: A) and B) Kathleen Carey, UF/IFAS Wildlife Ecology and Land Management Lab. C) Moriah Boggess, UF/IFAS Disturbance Ecology and Ecosystem Restoration Lab.

An example of a simple food preference study would be to monitor multiple food items and record the rate at which each item is consumed. Experiments can be modified by species. To monitor smaller animals, such as rodents, having a bin or bucket set up with a small entrance cut out will provide more exclusive access to food for these species (Figure 3A and Figure 3B). If the primary goal of a study is to understand the feeding habits of wildlife on large seeds or fruits (e.g., acorns or blueberries), simply placing the seeds on trays and pointing a camera trap towards the tray will capture this behavior (Figure 3C). Experimenting with this setup, you can answer questions such as the ones below.

- Which species observed are carnivores, omnivores, and herbivores?

- Do certain species avoid or show preference for specific food items?

- Do multiple species feed on the same food items?

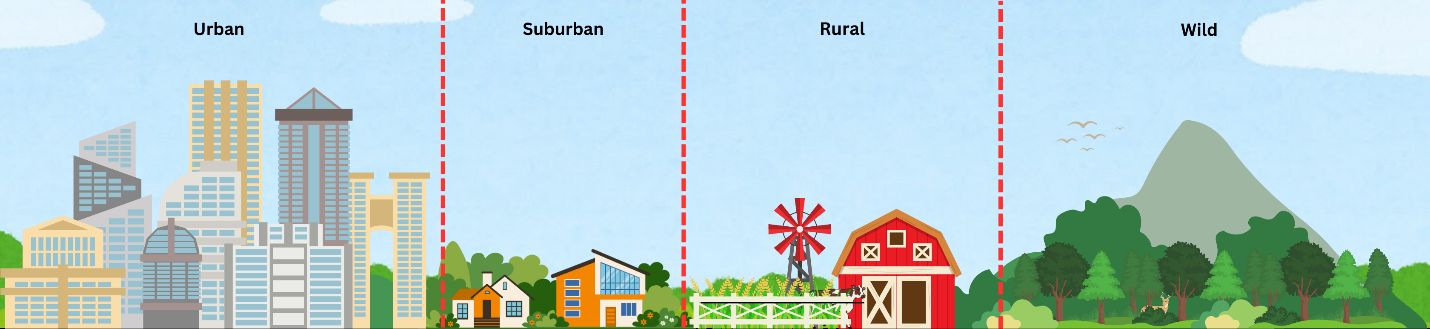

Human Activity

The habitat needs of wildlife species differ. While some animals require vast wild areas where people rarely roam, others are right at home in the biggest cities in the world. To understand how human proximity alters wildlife behavior, we can monitor wildlife in areas with varying levels of human activity. Setups can be as simple as placing one camera in a developed schoolyard and one camera in a nearby forest. For larger-scale setups, you can place cameras across a gradient, including urban (e.g., cities, heavily developed areas), suburban (e.g., neighborhoods), rural (e.g., agricultural zones and scattered housing with yards), and wild areas (e.g., large state and national parks) (Figure 4). This setup is more common if you can place cameras on a large property or in multiple areas. Setting cameras across a gradient that captures some or all these differences in development and human activity can provide the opportunity to ask very interesting questions about wildlife behavior.

Credit: Brandon McDonald, UF/IFAS Wildlife Ecology and Land Management Lab.

Comparing where and how often different species are detected across a gradient can provide insight into species’ needs and their preferences (or tolerance) to different levels of human activity. In an educational setting, this analysis can be expanded by making predictions about where certain species will be more likely to occur. Students can compare their predictions to the camera trap results and discuss the adaptations that may help or hinder wildlife of various shapes, sizes, and diets across the gradient. Examples of specific questions include the following.

- Where are certain species most likely to occur?

- Which species are detected in areas with high human activity compared to areas with low human activity?

- Does the diversity of species change across the gradient of human activity (high, medium, low)?

Ecosystem Engineers

As some species interact with their environment, they modify their own habitat, thus generating resources for other species. These species are called ecosystem engineers. The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) is one of the most well-known examples. When beavers construct a dam, they restrict water flow in streams, often resulting in the creation of wetlands that provide new habitat for a variety of species. Their lodges can also be used by other species, such as muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus), as shelter. There are many other ecosystem engineers that can be monitored with cameras, such as the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus; Figure 2A), and animals that create wallows, such as the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis).

An ecosystem engineer camera setup will depend on the size of the species in question and the kind of environmental features they alter. For larger species that alter wide areas, you can use a standard setup. Species that construct structures belowground or high up may require additional considerations and targeted camera deployment. This deployment may require changing the height of a camera, and may require the use of additional tools, such as a tripod or camera stake, to achieve a view that best captures the feature in question. Keep the camera far enough to focus on the target, typically 2–3 feet. If you deploy cameras in nearby unaltered locations as well, you can gain insight into the roles ecosystem engineers may play in their communities by comparing the number of species and detection rates between locations. For an effective comparison, use the same angle and height for the camera setup at each location. As a class, you can explore questions such as the ones below.

- What species do you observe in unaltered areas compared to areas altered by ecosystem engineers?

- Are there more species of wildlife in areas altered by ecosystem engineers?

- In areas with ecosystem engineers, what modifications do you notice to the landscape?

Pollinators

Pollinators are another group of species that can be valuable to study. These animals are crucial for biodiversity and global food production; nearly 80% of flowering plant species benefit from pollinators. Common pollinators include bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. There is a need for long-term monitoring initiatives among public, private, and research sectors to establish the status and trends of pollinator populations. One major issue with this endeavor is that conventional approaches through human observation make these broad community data logistically difficult or impossible to obtain.

Camera traps have been used in many studies to answer questions about pollinator diversity and behavior by utilizing continuous video recording. Downsides to these video recording systems are the limited battery life and the lengthy processing time required to extract usable data. On the other hand, commercially available game cameras with close-focus functionality and either motion-activated or timed interval settings (e.g., the Bushnell NatureView HD model 119740) may be a fun and easy tool for educators to use in the classroom to monitor pollinators. Students can conduct their own research on school grounds, community gardens, or in their backyards. Furthermore, quality photos can be posted to services like iNaturalist for expert identification and contribute to publicly available citizen science data. Questions you can ask your students using this camera setup include the following.

- What pollinators are in the observed area?

- What time of day are pollinators most active?

- Do different pollinator species prefer specific types of flowers?

Using iNaturalist to Learn More about the Observed Species

Identifying animals captured on camera traps can be challenging. Thankfully, the iNaturalist platform provides a helpful way to identify species in camera trap images. iNaturalist is a global citizen science platform that connects naturalists worldwide through its website and application (www.iNaturalist.org). To participate, simply upload a photograph with the date, time, and location of the observation (see the Add an Observation help page for more information). iNaturalist’s computer vision will then suggest possible species based on the image and location. Choose the species that best matches the image. If none of the suggestions seem accurate or you are unsure, the observation should be identified to the major taxonomic group you can determine (e.g., mammal, reptile, bird, or insect).

Once posted, the observation will be shared with the iNaturalist community, where other naturalists may help refine the identification. Check back on iNaturalist to see the community's identification suggestions for your observations. If two-thirds of the community agree on an identification at the species level, then the observation will become research grade and your observation will receive a green “research grade” banner. This designation indicates the community agrees on the identification of the species, and the observation is recommended for use by scientists. To learn more about the species observed, navigate to the species information page by clicking on the species name from “Your Observations” page. Here you will find additional photos of the species, a map of iNaturalist observations, the number of observations of the species per month, a page about the species powered by Wikipedia, and a plethora of other information. Together with your classroom, you can answer questions such as the ones below.

- When is the best time to find this animal?

- Which local parks have this species?

- Is this species native or introduced?

In addition to obtaining identifications on species you observe, you may also use iNaturalist to find out more about species present in your region, which can help inform camera trap targets. To do this, visit the Explore page (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations) and enter a region in the location box. Searches can be done by state, county, city, or even local parks. Navigate to the “Species” tab to view a list of species in the area. This page is automatically sorted from most common to least common species. If you are interested in a specific group of animals (e.g., mammals, birds, insects), use the “Species” filter to view a list ranked by commonality within that group.

Conclusion

Camera traps provide a lens in the classroom by using remote observation to ask and answer ecological questions. Educators and students can use camera traps as a tool to learn more about wildlife species by coming up with testable hypotheses on concepts such as wildlife daily activity, feeding preferences, human activity, ecosystem engineers, or pollinators. iNaturalist can aid in species identification and further educate students on the variety of species in their area. Commercially available camera trap brands include Browning, Bushnell, Reconyx, Moultrie, Primos, Spypoint, and Stealth Cam. Happy monitoring!

References

Barrueto, M., A. T. Ford, and A. P. Clevenger. 2014. “Anthropogenic Effects on Activity Patterns of Wildlife at Crossing Structures.” Ecosphere 5(3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00382.1

Boggess, C. M., C. Baruzzi, H. D. Alexander, B. K. Strickland, and M. A. Lashley. 2022. “Exposure to fire affects acorn removal by altering consumer preference.” Forest Ecology and Management 508: 120044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120044

McDonald, B. W., C. Baruzzi, R. A. McCleery, M. V. Cove, and M. A. Lashley. 2023. “Simulated extreme climate event alters a plant-frugivore mutualism.” Forest Ecology and Management 545: 121294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121294

McDonald, B. W., B. Mason, C. T. Callaghan, M. A. Lashley, and C. Baruzzi. 2025. “Camera Trapping for Wildlife: WEC472/UW530, 2/2025.” EDIS 2025(2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-uw530-2025

Naqvi, Q., P. J. Wolff, B. Molano‐Flores, and J. H. Sperry. 2022. “Camera traps are an effective tool for monitoring insect–plant interactions.” Ecology and Evolution 12(6): e8962. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8962