This Wildlife of Florida Factsheet is one in a series of publications that were created to provide the public with a quick and accurate introduction to Florida's wildlife, including both native and invasive species. We hope these factsheets inspire people to investigate wildlife in their own backyard and communities to understand the amazing biodiversity of wildlife in the state of Florida.

Scientific Name

Crotalus adamanteus

Common Name

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake

Breeding

Late summer into fall; may also happen in spring

Habitat

Open-canopy pine savanna environments, including dry sandhills, scrub, flatwoods, grassy areas of coastal barrier islands

Status

Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes have declined throughout their range. They are currently under review for listing under the Endangered Species Act and are state-listed as endangered in North Carolina.

Physical Description

Heavy-bodied with a thick, triangular-shaped head. Bold patten of yellow-bordered black diamonds on the back. Two black streaks on either side of the face present a mask-like appearance. Distinct rattle at end of tail. Young look like miniature adults but with a single basal rattle or “button” when they are born.

Length

Up to eight feet, but typically three to six feet; largest species of rattlesnake in the world

Reproductive Rate

Females can reproduce when three years old, and produce an average litter of 14 live young every two to three years

Lifespan

Up to 20 to 30 years in the wild

Dispersal and Home Range

Average 200 acres for males, and 50 to 75 acres for females. Male home ranges can be as large as 765 acres because they move long distances during the breeding season (Waldron et al. 2006). On average, eastern diamondbacks move about 30 feet a day or less, but during the breeding season they can travel twice that far (Kelley et al. 2022). They tend to move in the morning and evening during the summer. Adults move to underground sites in the winter. These include tree-stump holes and armadillo and gopher tortoise burrows (see species account by D.B. Means in Krysko et al. 2019).

Biology and Behavior

Eastern diamondbacks are considered to have a “slow” biology (Waldron et al. 2013). Although females can reproduce as young as three years old, most reproduce only after about seven to ten years. Because reproduction is energetically costly, females give birth to 10 to 14 live young every two to three years (Fill et al. 2015a; see species account by D.B. Means in Krysko et al. 2019), but few baby rattlesnakes survive due to road mortality, human persecution, predators, and other natural threats to their survival. On the other hand, adult snakes have few predators and can live for more than 20 years, but intentional killing by people and road mortality take their toll. Many individuals encountered today are smaller than their maximum size, however, because adults grow slowly and are often killed before they can reach that size. Therefore, it is important for a population to have healthy adult females who live for a long time.

Rattlesnake home ranges don’t vary much from year to year. Within a year, male home ranges can be large because they travel long distances during the mating season in search of females. Males are at especially high risk of mortality during the mating season because they move across roads and through suburban environments in search of females. The primary reproductive season for diamondbacks is autumn, but mating can happen in spring. After mating, females may store sperm over the winter, fertilize eggs in spring, and give birth to live young the following autumn (August–September). Birthing sites are usually well-concealed areas around large fallen logs or in burrows.

Diamondbacks are active for at least seven to eight months of the year. During the winter, diamondbacks will use stump holes and eastern woodrat (Neotoma floridana), gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), and nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) burrows for shelter (Means 2017; Murphy et al. 2021). On warm winter days, however, diamondbacks can be found outside their shelters basking on the ground. In the southern part of their range, especially in Florida, the warm winters generally allow the snakes to be active nearly year-round (Martin and Means 2000).

Adult diamondbacks are especially vulnerable to habitat loss. Although young rattlesnakes will disperse from their birth sites, adult snakes tend to remain in their established home ranges even if the habitat becomes less and less suitable for survival (Waldron et al. 2013). Eastern diamondbacks are not territorial, but their high “site fidelity” means that conserving or restoring good habitat is important for their survival (Waldron et al. 2008; Greene et al. 2019; Fill et al. 2015b). Some studies suggest, however, that rattlesnakes can be translocated to other areas without obvious adverse effects, at least in the short term (Kelley et al. 2022). Nonetheless, it is not a viable conservation strategy to rely only on moving rattlesnakes in order to save individuals, avoid conflicts with people, and accommodate development.

History

The eastern diamondback rattlesnake is the largest rattlesnake in the world (Figure 1). It is only found in the southeastern United States, and within that area its range and population numbers have shrunk dramatically as a result of habitat loss, habitat fragmentation by roads, and collection and killing by people, including during “rattlesnake roundups” (Means 2009; Stohlgren et al. 2015). This species is currently under review by the US Fish and Wildlife Service for listing under the Endangered Species Act. Although it is not as commonly seen in the wild as other snakes because of its secretive nature, the eastern diamondback is still feared and not well understood by many people who encounter it. A better understanding of rattlesnakes helps people know how to act safely around them and to respect them and their natural habitats.

Credit: Jennifer Fill, UF/IFAS

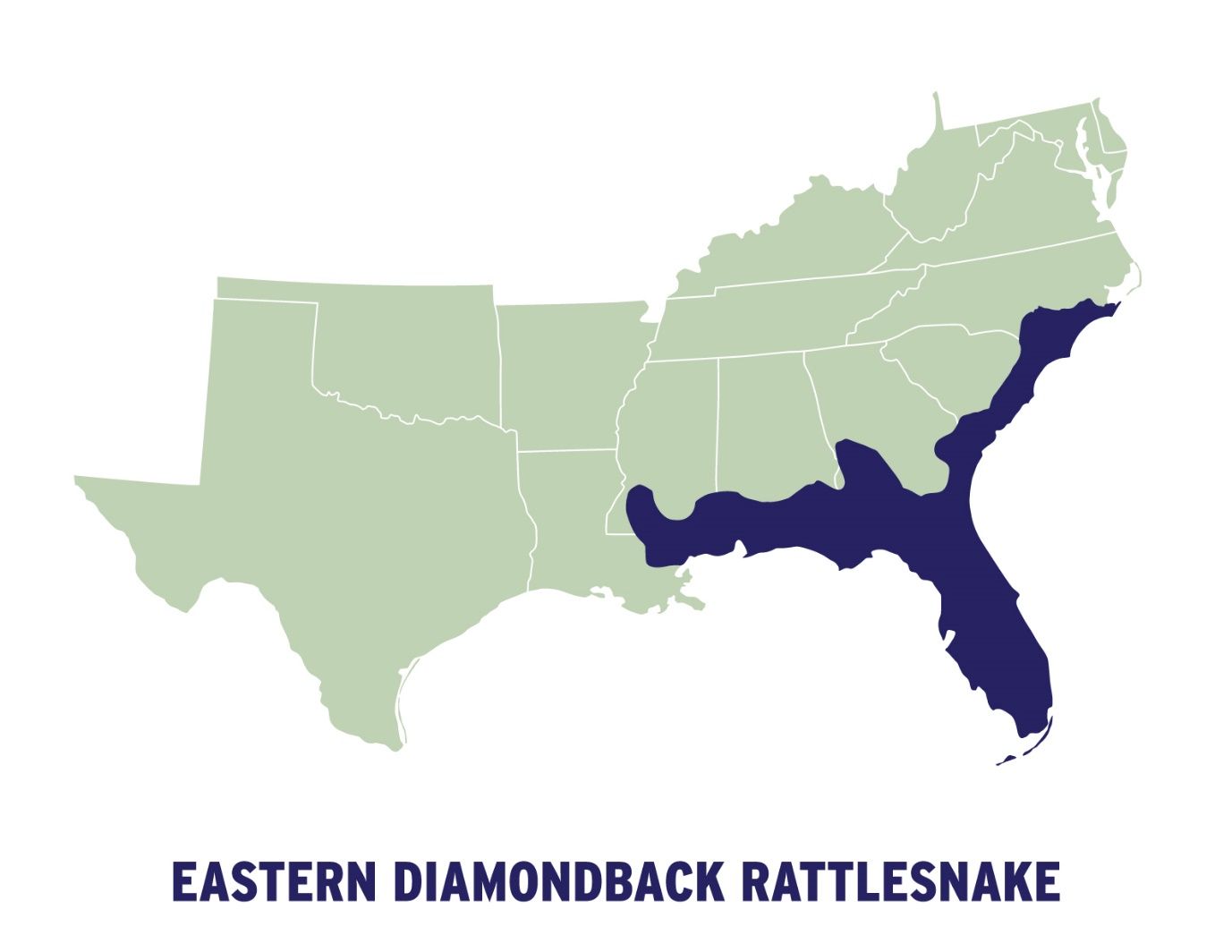

Distribution

Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes only occur in the extreme southeastern United States (Figure 2). Their historical range is closely aligned with the historical range of pine savannas, including southeastern North Carolina through Florida and west to eastern Louisiana, although they are considered currently extirpated from Louisiana and nearly so from North Carolina (Martin and Means 2000; Timmerman and Martin 2003). Eastern diamondbacks can be found not only on the mainland but also on barrier islands, especially those off the coasts of Georgia and Florida (Stohlgren et al. 2015; Means 2017).

Credit: Tracy Bryant, UF/IFAS

Natural Habitat

Eastern diamondbacks are considered open-canopy habitat “specialists” (Waldron et al. 2008). Diamondbacks are strongly associated with habitats that are open and sunny and that have abundant grass groundcover, especially upland pine savannas (Fill et al. 2015b; Means 2017). Upland pine savannas have a sparse canopy cover of pine trees like longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) and slash pine (Pinus elliottii) and a groundcover of bunchgrasses, shrub patches, and diverse herbaceous plants. Pine savannas naturally burn often, around every two to three years, and this helps keep the environments open and grassy enough to support large-bodied prey such as cotton rats, fox squirrels, and rabbits. The eastern diamondback rattlesnake’s yellow and black diamond pattern camouflages the snake in these grassy and brushy habitats (Figure 3). Diamondbacks will wait in ambush for several days when hunting. They coil near palmettos, fallen logs, or shrub patches waiting for mammal prey to pass withing striking distance (Figure 4).

Credit: Jennifer Fill, UF/IFAS

Credit: Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS

Human Encounters: How to Coexist with Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes

The expansion of human populations into diamondback rattlesnake habitats has brought people and snakes into more frequent contact. Snakes are often purposely killed by fearful humans, and they are frequently hit and killed by vehicles as they move across roads, especially during the mating season. Loss of sufficient habitat area to support their prey, because of development or fire suppression, has also contributed to their range-wide decline.

The best way to avoid a bite from an eastern diamondback, or any venomous snake for that matter, is to leave it alone. Far from being aggressive, the eastern diamondback typically reacts to human encounters by staying still and camouflaged. If molested, it will usually try to flee. If it cannot get away, a snake might assume the quintessential defensive posture and begin rattling, often still trying to back away (Figure 5). Rattlesnakes are not inherently aggressive and do not seek out humans as prey. Venom is also energetically expensive for a snake to make and is not typically used for killing predators.

Credit: Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS

The venoms of pit vipers, which include rattlesnakes, are complex mixtures of proteins and protein-destroying enzymes which cause muscle and organ damage. In the unlikely event of a bite, the best thing to do is stay calm and seek immediate medical attention—call 911! Do not cut the area around the bite or try to suck the venom out of the wound; do not apply a tourniquet; do not apply pressure; do not apply ice or heat.

As noted above, the best way to coexist with rattlesnakes is to leave them alone to play their ecological roles as predator, and prey, in the environment. In fact, eastern diamondbacks provide a valuable ecological service to humans because their diet includes rodents, which can be pests around human dwellings. Nonetheless, if you want to discourage rattlesnakes from your yard, see the UF/IFAS publication “Coexisting with Venomous Snakes” to learn about actions you can take to make your property less attractive to all snakes. When hiking in rattlesnake territory, stay on maintained trails, watch your step, and wear closed-toed shoes. If you are especially concerned about rattlesnakes, you might consider wearing protective leg guards, called “snake chaps” or “snake boots” that are made of thick material that protects against venomous snakebite. If you do encounter an eastern diamondback rattlesnake, give it a wide berth and enjoy the encounter from a distance. They are beautiful and impressive animals worthy of our respect and admiration.

Literature Cited

Fill, J. M., J. L. Waldron, S. M. Welch, et al. 2015a. “Breeding and Reproductive Phenology of Eastern Diamond-Backed Rattlesnakes (Crotalus adamanteus) in South Carolina.” Journal of Herpetology 49:570–573. https://doi.org/10.1670/14-031

Fill, J. M., J. L. Waldron, S. M. Welch, J. W. Gibbons, S. H. Bennett, and T. A. Mousseau. 2015b. "Using Multiscale Spatial Models to Assess Potential Surrogate Habitat for an Imperiled Reptile.” PLoS One 10 (4): e0123307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123307

Greene, R. E., R. B. Iglay, and K. O. Evans. 2019. “Providing Open Forest Structural Characteristics for High Conservation Priority Wildlife Species in Southeastern US Pine Plantations.” Forest Ecology and Management 453:117594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117594

Kelley, A. G., S. M. Welch, J. Holloway, J. W. Dillman, A. Atkinson, and J. L. Waldron. 2022. “Effectiveness of Long‐Distance Translocation of Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes.” Wildlife Society Bulletin 46:e1291. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.1291

Krysko, K. L., K. M. Enge, and P. E. Moler. 2019. Amphibians and Reptiles of Florida. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, FL. 706 pp.

Martin, W. H., and D. B. Means. 2000. “Distribution and Habitat Relationships of the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus).” Herpetological Natural History 7:9–34.

Means, D. B. 2009. “Effects of Rattlesnake Roundups on the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus).” Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4:132–141.

Means, D. B. 2017. Diamonds in the Rough: Natural History of the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake. Tall Timbers Press, Tallahassee, FL. 416 pp.

Murphy, C. M., L. L. Smith, J. J. O’Brien, and S. B. Castleberry. 2021. “Overwintering Habitat Selection of the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) in the Longleaf Pine Ecosystem.” Herpetological Conservation and Biology 16:203–210.

Stohlgren, K. M., S. F. Spear, and D. J. Stevenson. 2015. “A Status Assessment and Distribution Model for the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) in Georgia.” The Orianne Society. https://gastateparks.org/sites/default/files/wrd/pdf/research/GaStatus_DistributionModel_EasternDiamondbackRattlesnake_Report.pdf

Timmerman, W. W., and W. H. Martin. 2003. “Conservation Guide to the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, Crotalus adamanteus.” Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Herpetological Circular No. 32.

Waldron, J. L., S. H. Bennett, S. M. Welch, M. E. Dorcas, J. D. Lanham, and W. Kalinowsky. 2006. “Habitat Specificity and Home‐Range Size as Attributes of Species Vulnerability to Extinction: A Case Study Using Sympatric Rattlesnakes.” Animal Conservation 9:414–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00050.x

Waldron, J. L., S. M. Welch, and S. H. Bennett. 2008. “Vegetation Structure and the Habitat Specificity of a Declining North American Reptile: A Remnant of Former Landscapes.” Biological Conservation 141:2477–2482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.008Get rights and content

Waldron, J. L., S. M. Welch, S. H. Bennett, W. G. Kalinowsky, and T. A. Mousseau. 2013. “Life History Constraints Contribute to the Vulnerability of a Declining North American Rattlesnake.” Biological Conservation 159:530–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.11.021