Introduction

Taking time to observe and understand horse behavior can contribute in a positive way to the horse’s well-being and to our daily human-horse interactions. A better understanding of a horse’s natural behavior and preferences can facilitate more effective horse management and handling skills. Additionally, regular observation of horses with an understanding of the typical behavior of each horse allows for early recognition of behavioral (e.g., training issues) and physical problems (e.g., lameness, illness) and appropriate intervention. This publication is intended for equine owners, equine farm managers, county Extension faculty, and anyone working with or interested in horses.

Natural Behaviors of the Horse

Over the course of their evolutionary history as a prey species, horses developed survival mechanisms that remain a motivation for much of their behavior today. Their means of survival, a strong flight response, was adapted to help them escape from predators. Domesticated horses have maintained their innate reactions to unknown or fear-inducing stimuli. When faced with a potential threat, the horse naturally has a strong avoidance reaction, which can lead to fleeing from the source of the threat. When afraid, horses may also freeze. If the horse cannot escape a fearful situation, it may rely on its fight response and resort to kicking and/or biting as a means of defense.

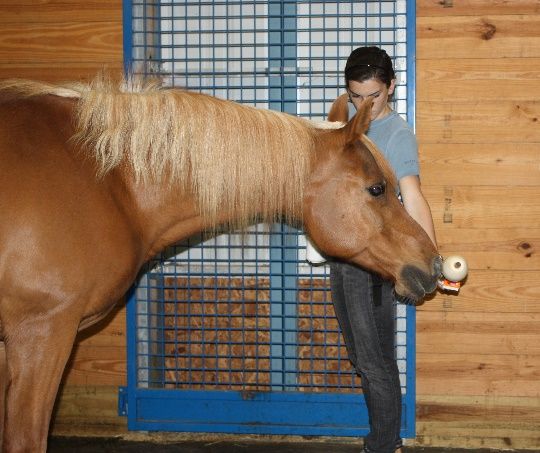

Horses possess many traits that made them suitable candidates for domestication. Horses could be managed on a variety of forages and grains, which allowed them to adapt to various locations. Their easygoing disposition and trainability, ability to reproduce successfully in captivity, and social structure allowed humans to train the horse for occupational and recreational purposes (Figure 1). To better understand a horse’s disposition and health status, monitor its behavior and daily activity level closely. Optimal horse management requires careful observation of horse behavior and body posture, and consideration of feeding, social grouping, exercise access, and the horse’s natural behavior.

Credit: Carissa Wickens, UF/IFAS

Ingestive (Feeding) Behavior

The horse’s anatomic structure was designed for continuous grazing on a variety of plant species. The horse is equipped with a small stomach and is therefore best suited to consume small meals over the course of the day. Additionally, salivation is a mechanical response to chewing. Production of saliva aids in buffering stomach acid. Providing the right type of feed on a schedule that allows a horse the opportunity to chew much of the day satisfies both physical (i.e., maintaining proper gastrointestinal function and health) and psychological (i.e., engaging in natural foraging behavior) needs of the horse.

Providing horses with adequate forage is a good thing. Many horse owners try to optimize the use of pasture on farms to help reduce costs associated with purchasing hay. However, special management strategies need to be implemented to accommodate the grazing behavior of horses. Domesticated horses confined to pastures or small lots will tend to overgraze certain areas of their enclosure while avoiding other areas. Short grass areas (lawns) are more desirable to horses because the forage is more tender and of higher nutrient value. If grazed too short, rootstock can be damaged, and the grass cover can be lost completely. Additional areas of the pasture may consist of roughs. Roughs are characterized by the presence of taller, more mature plants and are usually the sites for defecation and urination. To manage these distinct feeding and defecation areas, regular mowing and harrowing of pastures are recommended for better use of the available forage. Careful monitoring of pastures is necessary to maintain ground cover and ensure optimal forage utilization. For more information on the management of pastures and forage crops for horses, see Ask IFAS publication SS-AGR-65, “Pastures and Forage Crops for Horses,” at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AA216.

It is not always possible or feasible to keep horses on pasture 24/7. When horses need to be confined to a stall, it is still important to allow for continuous food intake and to base the diet primarily on forage. It is best to avoid large grain meals high in soluble carbohydrates. Hay and grain rations can be divided into smaller, more frequent feedings. Feeding hay from hay nets or in a slow feeder can extend the amount of time spent foraging. By following these guidelines, owners can take steps towards minimizing digestive complications such as colic and gastric ulcers as well as behavioral problems (e.g., stereotypic behaviors) associated with a lack of foraging opportunities.

Water intake for horses is crucial and often overlooked. Horses will visit the water bucket or trough a few times a day or more frequently depending on exercise, diet, and climate conditions. Water temperature could be a factor that negatively impacts intake. Some horses refuse to drink extremely warm or extremely cold water. Reduced water intake can cause the horse to become dehydrated or at increased risk for impaction colic. As a general rule, clean and fresh water should be available at all times.

The Significance of Body Language

Observing changes in the horse’s posture, head and tail carriage, facial expressions, and positioning of the legs and ears can provide vital clues about the horse’s feelings and intentions. For example, take notice whether the eyes are wide, the nostrils are flared, and the ears are pinned back or pricked forward and alert. Is the horse’s tail clamped tight with nervousness or wringing with frustration, or is it simply swishing rhythmically when the horse changes leads? It is normal for horses to rest a hind foot when standing. However, pointing with a front foot and constant weight shifting between left and right front or hind feet (“treading”) are signs of discomfort that warrant further attention. The facial expressions shown in Figure 2 are characteristic of a horse that is experiencing pain. These are all important features that provide insight into the mental condition of the horse. Behaviors and body language should be taken in context with the horse’s immediate surroundings or circumstances. Sudden changes in the horse’s overall appearance and demeanor may indicate a physical problem. Providing this information to an attending veterinarian can aid in diagnosis and treatment, which may improve prognosis and help speed recovery.

Credit: Carissa Wickens, UF/IFAS

Equine Social Structure

Feral horses (free-ranging horses of domesticated ancestry) organize themselves into small, relatively stable herds. These small herds (bands) typically consist of a stallion, several mares, and their offspring. Within these feral herds, some of the horses will form strong bonds with one another. For example, horses will engage in mutual grooming and graze in close proximity. Horses will form dominance structures in which certain horses may be subordinate to others in the group. These same social behaviors are observed in our domestic horses. However, these social relationships are dynamic rather than static and are often influenced by the type and availability of resources (e.g., feed, shelter access).

Vigilance behavior is an important category of behavior observed in all horses. This occurs when one member of the group surveys the horizon for danger (Figure 3). When one horse becomes alerted to a predator, the others in the group adopt an alert state. This triggers an escape response among all the horses in the group. A good example of this behavior in our domesticated horses is when one horse on a group trail ride spooks at something in its path, and almost immediately the rest of the horses begin to spook even though they may not know what they are fleeing from.

The horse’s social structure can cause management difficulties. Some horses become anxious when separated from herd mates, which makes them difficult to handle. For instance, when one horse is taken on a trail ride, the herd mate left behind in the paddock may begin to vocalize, pace, and/or run the fence line. Keeping the anxious horse in a safe area is important (e.g., fencing should be in good condition and provide both a physical and psychological barrier to prevent escape and/or injury). Providing forage and/or horse-safe toys may be helpful in redirecting the anxious behavior. With performance horses that become anxious when separated during a show or event, it may be beneficial to house them in separate aisles of the barn and to practice short bouts of separation before the competition. When introducing new horses to existing and established social groups, there will always be a period of adjustment in which the members of the group attempt to reorganize their social order. Introductions of newcomers to the herd should be done gradually. Following an observed quarantine period to ensure the new horse will not expose resident horses to disease, you can begin allowing the horses to become acquainted by housing them in adjacent paddocks. Newly mixed groups of horses should be diligently monitored in case intervention becomes necessary to avoid injuries or to maintain adequate access to resources such as feed, water, and shelter. Allowing sufficient space between feeders or hay piles and avoiding overcrowding will help minimize aggressive behavior within the group. Horses rarely engage in overt fighting, and agonistic interactions often do not escalate beyond threat displays (e.g., pinned ears).

Credit: Carissa Wickens, UF/IFAS

Providing Exercise and Play

Supplying horses with adequate exercise and opportunities to engage in play behavior is also an important part of their management. The level of exercise each horse receives will depend on their body condition, weight, age, level of training, and intended use. Providing the horse with some controlled exercise in the form of riding, driving, or groundwork will keep the horse healthy and maintain its responsiveness to handling and training. When a horse can demonstrate play behavior, we can more easily assume that the horse is experiencing good welfare (although a more recent study [Hausberger et al. 2012] suggests that play behavior may also be utilized by horses as a means of coping with stress). Play behavior, including object play (e.g., with a ball) and play fighting, is especially important in young horses. These behaviors equip juvenile horses with necessary skills and useful information about their surroundings. All horses, both young and adult, are exhibiting locomotive play when they sprint across the paddock or pasture. This type of play has been shown to be beneficial to musculoskeletal development in young, growing horses. Allowing free movement (e.g., providing regular turnout) can be beneficial for horses with arthritis and conditions such as polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM). In addition, turnout with other horses allows each horse a chance to socialize. Even in situations where group turnout is not possible, turning horses out in adjacent paddocks provides them with fence-line contact and affords them some level of tactile communication (Figure 4).

Credit: Carissa Wickens, UF/IFAS

Take-Home Message: Tips for Incorporating Behavior into Horse Management

- Become an observer of horse behavior. This will improve your ability to anticipate and react appropriately and safely to certain situations that arise when working around horses. Moreover, it will provide you with a better sense of what behaviors are normal for the horses you own or work with, making it much easier to detect abnormal behavior and address potential health and/or training issues.

- When designing the layout of your horse’s environment, keep in mind that sharp corners and areas where horses can become trapped by a dominant pasture mate should be avoided.

- Consider horses’ natural feeding behavior and base the diet on forage first. Provide frequent, small meals.

- Consider natural social behavior. Gradually introduce new horses into the existing herd and maintain the social organization (herd dynamics) on your farm to reduce conflicts among pasture mates.

- Consider locomotor and play behavior and routinely provide sufficient room for movement.

Overall, the consideration of natural behavior leads to refined management practices that improve horse welfare and performance.

References

Hausberger, M., C. Fureix, M. Bourjade, S. Wessel-Robert, and M.-A. Richard-Yris. 2012. “On the significance of adult play: What does social play tell us about adult horse welfare?” Naturwissenschaften 99(4): 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-012-0902-8

McDonnell, S. M. 1999. Understanding Horse Behavior. Lexington, KY: The Blood-Horse, Inc.

TenBroeck, S. 2017. “The Nature of the Beast – Understanding Horse Behavior.” UF/IFAS Extension. https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/phag/2017/07/07/the-nature-of-the-beast-understanding-horse-behavior/

Wickens, C. 2019. “Recognizing and Addressing Behavioral Problems: What Is Your Horse Telling You?” UF/IFAS Extension. https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/phag/2019/03/08/recognizing-and-addressing-behavioral-problems-what-is-your-horse-telling-you/

Wickens, C., and C. Heleski. 2024. “Is it coping or is it a vice? Understanding stereotypic behaviors in horses: VM257, 1/2024.” EDIS 2024(1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-vm257-2024