Introduction

Relationship-based leadership is characterized by trust, respect, and mutual obligation that generates influence between parties (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Within Extension especially, many relationships between supervisors and employees (i.e., County Extension Directors (CEDs) and Extension agents; District Extension Directors (DEDs) and CEDs) are dynamic and multidimensional, characterized as both supervisory and collegial. Kouzes & Posner (2010) reported that a leader's behavior contributes to 25% of why employees feel productive, motivated, energized, effective, and committed to their work. The interactions between supervisors and employees are critical to maintaining positive relationships and can help determine the support necessary for Extension supervisors through professional development and training opportunities.

Benefits of Understanding and Yielding High-Quality Relationships within the Workplace

Leadership is not a one-way street, but rather a highway the leader and employee (i.e., CED and Extension agent) pave together. Positive interactions lead to increased employee productivity, efficiency, and job satisfaction, whereas negative relationships yield the opposite (Castillo & Cano, 2004). Mikkelson, York, and Arritola stated "most employees want to have good relationships with their supervisor" (2015, p. 348). Low-quality relationships yield minimal communication and less influence, confidence, and concern (Benge & Harder, 2017). Self-knowledge, energy, and support that fuel growth and development are also found within high-quality relationships (Ragins & Dutton, 2007). In the excerpt below, Carmeli, Brueller, and Dutton (2009, p. 83) provide a detailed explanation as to outcomes of high-quality relationships between supervisors and employees:

The capacities enabled by high-quality interpersonal relationships allow members to exchange more variable information and ideas which are critical to creating and sharing solutions to problems and new ways to improve work processes and outcomes. At the same time, participants in high-quality relationships feel valued and connected in ways that allow them to overcome the uncertainty that accompanies working through problems and experimenting with solutions.

Leader-Member Exchange Theory

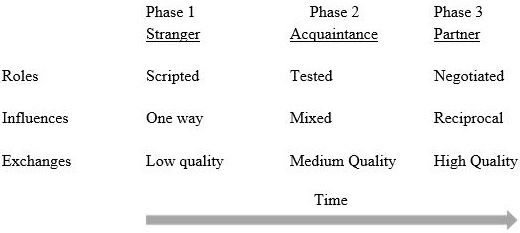

Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX) is a relationship-based approach that explains leadership as an interaction between both leader and follower (i.e., CED and Extension agent) (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Interactions by both the leader and follower produce the relationship, and over time the relationship moves from transaction to transformation. Leadership, or leadership-making, occurs in three stages over time: (a) the stranger phase, (b) the acquaintance phase, and (c) the partner phase (Figure 1). The new relationship between a leader and follower begins in the stranger phase and moves to the partner phase through positive interactions over time. Relationships that remain stagnant never pass the acquaintance phase and eventually revert to the stranger phase of leadership.

Credit: Graen & Uhl-Bien (1995)

Phase 1: Stranger Phase—Leader-member interactions occur on a formal basis, are lower-quality exchanges, and are purely contractual.

Phase 2: Acquaintance Phase—Contractual exchanges begin to decrease and roles are redefined, where both leader and member focus less on self-interests and more on the mission of the office or organization.

Phase 3: Partner Phase—Mutual trust, obligation, and respect are experienced by both leader and member. Loyalty and support are reciprocated, and the relationship is transformational.

Instrumentation to Measure the Relationship

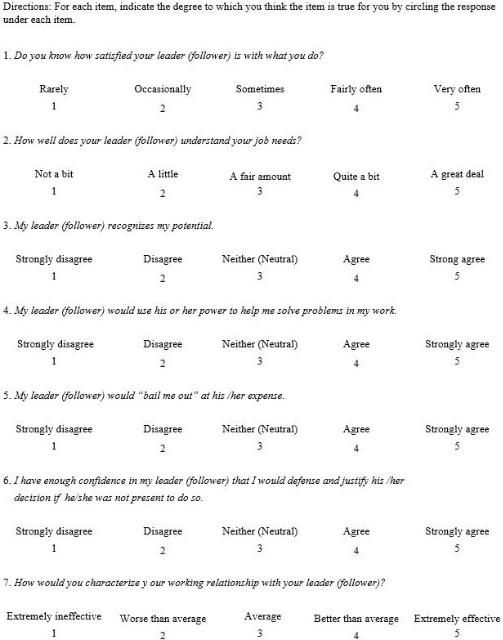

The assessment instrument, the LMX-7, is a seven-item questionnaire (Figure 2) that determines the phase of leadership-making between a supervisor and employee (Maslyn & Uhl-Bien, 2001). Some of the items were reworded for clarity and because some were double-barreled, and the original scales were adjusted to reflect these changes (Benge & Harder, 2017). The updated LMX-7 was pilot tested and yielded a Cronbach's alpha of .94.

Credit: Benge & Harder (2017)

Both the leader (i.e., CED) and follower (i.e., Extension agent) complete the instrument separately. The LMX-7 is interpreted by adding the scores of each item, creating a total score separately for both the leader and follower (Table 1).

Interpretation

Both Yield High Scores—If both the leader and follower produce a high score, then both perceive the relationship to be transformational and mature. This is a positive sign, and organizations should want the majority (if not all) of relationships of over 3 years' duration to be in the partner phase of leadership-making.

Both Yield Low Scores—If the leader and follower produce low scores, then the relationship is in the stranger phase. First, this isn't necessarily a disadvantage because all new relationships begin in this phase. Organizations that have many new hires will naturally have many in this stranger phase. However, an organization should feel wary if the relationship has lasted longer than 3 years and nevertheless remains in the stranger phase. This signifies the relationship has not, and will most likely never, mature. These relationships will yield low employee job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and productivity when compared to those in the partner phase.

Mixed Scores—Leadership-making is a two-way street, wherein both the leader and follower pave the way. One of the two parties may contribute more effort, or may perceive that he or she has contributed more effort, than the other. More than likely, either the leader or follower is in the acquaintance phase, with the other in the stranger or partner phase. These relationships need extra time and attention in order to make the full push to the partner phase.

Conclusions

The relationship between a leader and follower has a direct effect on the employee's job satisfaction, work productivity, decision sharing, program implementation, and turnover intentions. Those who have a supervisory role should use the LMX-7 to gauge the quality of relationship between themselves and their employees. County Directors within Extension can use this to drive relationship-building with those they supervise and can use the results in their annual record of accomplishments. Administrators can use the results to drive training and development to help supervisors acquire the necessary skills to build and maintain relationships.

References

Benge, M., & Harder, A. (2017). The effects of leader-member exchanges on the relationships between extension agents and county extension directors in Florida. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 5(1), 35-49. Available at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/c8fe6e_abf482fce12b43e79bdc759ad61bce87.pdf

Carmeli, A., Brueller, D., & Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 26, 81-98. doi:10.1002/sres.932

Castillo, J. X., & Cano, J. (2004). Factors explaining job satisfaction among faculty. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(3), 65–74. doi:10.5032/jae.2004.03065

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (lmx) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2010). The truth about leadership: The no-fads, heart-of-the-matter facts you need to know. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mikkelson, A. C., York, J. A., & Arritola, J. (2015). Communication, competence, leadership behaviors, and employee outcomes in supervisor-employee relationships. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 78(3), 336-354. doi:10.1177/2329490615588542

Ragins, B. R., & Dutton, J. E. (2007). Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research foundation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahway, NJ.