Introduction and Purpose

This publication will focus on developing social media plans. The intended audience is individuals (e.g., scientists wishing to share their research), organizations, or people who work on grant-funded research projects. In this article, we provide evidence-based strategies for designing, developing, and implementing social media plans to share science research with others inside and outside of the professional scientific community. While the design, development, and implementation of social media may vary, we provide general strategies that are applicable across contexts. This is part of a multipart series on social media titled Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research.

Contextualizing Social Media

Social media plans can help you strategize effectively in order to share information or to have conversations with people surrounding a topic of interest using social media platforms, such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or TikTok. Successful adoption and management of social media platforms can enhance online communications (Daume & Galaz, 2016).

Successful Social Media Planning

Evidence-Based Strategies for Social Media Planning

You should consider three specific components when planning your social media strategy: goal-setting, platforms, and message design.

Goal-Setting

Establishing goals as part of creating a social media plan can help you capitalize on the features and communities that exist on each platform and ultimately measure your impact. Social media plans should include SMART goals—that is, goals that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable (i.e., Attainable), Relevant, and Time-Bound (Rubin, 2002). For an excellent EDIS document on SMART goals, see (Cothran, Wysocki, Farnsworth, & Clark, 2019). Below, we provide general examples of SMART goals for social media as well as a table that walks through all the components (Table 1).

Specific

- What do you want to accomplish? Why? How will your use of social media impact the community with whom you are communicating? This component of your goals relates to platform choice. Essentially, you need to be explicit about who you want to communicate with and how you want to do it. An example of this could be, "I want to develop a social media strategy for my grant-funded project so I can talk about the research generated by the project and the in-person events we're hosting with people who live in north Florida. North Floridians will benefit from this because they will have easier access to scientists and scientific findings that impact them and their community." This specific goal describes what you want to accomplish (develop a social media strategy) and why you want to do it (to share research and events related to a grant-funded project). Additionally, this goal indicates the community with whom you want to connect: people who live in north Florida.

Measurable

- How will you gauge success? An example of measurement is using the engagement rate of your social media posts to determine how your posts perform against external benchmarks (Lundgren et al., 2020). Are you hoping to have a specified number of quality interactions (messages, comments, etc.) with the community? Make sure your goal is something you can measure. For our grant-funded project example, it could be the number of people who report attending your event because they saw it on social media. For the research-sharing portion, it could be that you have a certain number of people engage with the post. For an in-depth discussion of evaluation, which is a way to measure the success of your social media, see the article in this series on evaluation.

Achievable (i.e., Attainable)

- What resources do you have to accomplish your goal? Acknowledge that social media planning is not necessarily a side gig: you or your team members will need to devote at least ten hours a week to planning posts, creating content, and interacting with your community. Social media managers exist and are paid professionals for a reason! That is not to say that you cannot have a social media presence without an external social media manager—just remember that quality content takes time. With that in mind, decide how much time and energy you have for creating and managing social media. If you can foresee having minimal time (i.e., 10 hours a week), limit the number of posts you create (2–3 posts per week). Consider as well how the time you commit to your goal relates to the importance of the goal. If you are interested in ensuring that north Floridians have easy access to scientific discoveries that impact them, how does this goal relate to the time you have, the time you want to do it in, and the needs of your community?

Relevant

- Decide the ways that creating and maintaining a social media presence is pertinent to you. Do you have time-limited or project-specific Broader Impacts requirements as part of a National Science Foundation grant, or Extension programming or grants through USDA? Are you trying to communicate with people locally or globally? Or are you building a general social media presence for the long term? Consider how social media is pertinent to your interests as well as the interests of the community with whom you want to connect. Social media is sometimes not the right answer, especially when you are trying to build a new relationship or group.

Time-Bound

- This component can be addressed in multiple ways. Think about what you envision your social media looking like and doing for you six weeks, six months, or six years from now. Short-term planning should be different from long-term planning. Keep in mind that not all social media experiences immediate exponential growth! For example, your six-week goal might be to post 2–3 times a week. Your six-year goal might be to win an award for excellence in science communication. If you have such goals, you need to establish timepoints that will help you to achieve these goals. Additionally, this component can help you manage expectations related to the community with whom you are communicating. Consider what skills, knowledge, relationships, or other aspects of community building you want your social media to help community members develop. Can those with whom you are communicating accomplish these outcomes within the timeframe you have indicated?

Choosing Your Platform

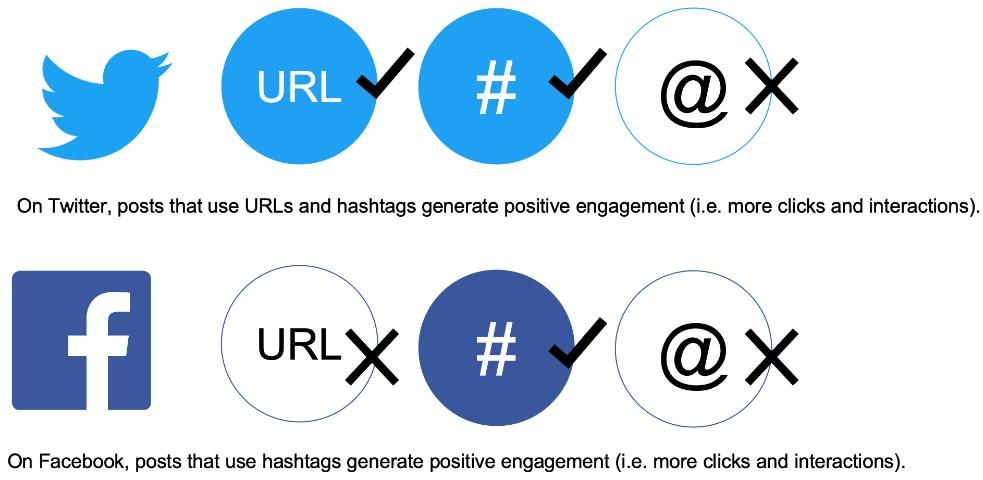

One of the most important parts of a social media plan is choosing which platform(s) to use. Platforms are unique, and many of them feature communities that prefer specific types of interactions with design elements (i.e., mentions, hashtags, photos, and URLs). For instance, hashtags (the act of aggregating information under a specific word or phrase) rule Twitter, with users often employing hashtags like #ScienceTwitter and #SciComm; hashtags can also be used to yield positive engagement (i.e., more reactions, clicks on posts, comments, etc.) on Facebook (Lundgren, Crippen, & Bex, 2020). Deciding on and researching which design elements are effective on individual platforms will help you to communicate messages that resonate with your community (Figure 1). While many social media practitioners recommend mentioning other users (i.e., using the @ symbol followed by a username), researchers (Lundgren et al., 2018) found for scientific conversations on Twitter, solely mentioning users does not generate high engagement rates. To have holistic conversations that are inclusive of many community members, we recommend that you use hashtags and mentions together in Twitter posts. As for Facebook, researchers found that using hashtags generates high engagement rates, while solely using mentions or URLs does not. Research on the most effective design elements for other platforms (e.g., TikTok and Instagram) is ongoing. You can find more on platform choice and current audiences in the accompanying EDIS document Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: Basics.

Credit: Lisa Lundgren

Messaging Based on Community and Post Types

After creating SMART goals and choosing your platform, you should plan posts around your specific community as well as establish the types of posts that you want to create.

Communities are often unique to platforms—this relates to the "S" in your SMART goals. When planning for social media content, create a list of the types of people who would interact with your content. For example, on a National Science Foundation–funded project called the FOSSIL Project, which was about connecting people who were interested in paleontology, the social media team worked with an outside agency to establish the types of people who would interact with social media. Together, the team developed three personas: professional paleontologists, who interact with social media as a way to share their research and find field work partners; educators, who sought to find expert help related to paleontological topics they could teach in schools; and amateur paleontologists, who wanted to meet one another to share their love of paleontology. The ways that these types of people interacted with content varied on the platform they used. For this reason, we recommend that in general you do not cross-post content, that is, post the same content verbatim to more than one platform. This means that the content you post on Twitter should be unique to Twitter and that community and purpose, the content you post to Instagram should be unique to Instagram, and so on. You should not post a message with only a link to a post you made for Instagram on your Twitter page.

After planning who will interact with your social media content, consider the design of your messages. Message design consists of creating graphics and writing text for your posts. When writing text for your posts, develop categories based on what you think your community will be interested in. Research into how communities engage with post content shows that people interact with some types of messages more than others (Lundgren et al., 2020; Cardoso, Warrick, Golbeck, & Preece, 2016). For instance, for a community interested in paleontology, researchers classified posts into four categories, information, news, opportunity, and research, and found that people interacted with posts that provided general resources for paleontology (i.e., information posts) at higher rates than any other post type (Lundgren et al., 2020; Bex et al., 2019). The takeaway from this is that you need to create different categories of posts; you should not merely share every media outlet story about your research, but rather you need to consider your community's personal interests to effectively communicate with them. You can choose to share content that is not directly related to your scientific work. Your posts can highlight other aspects of your life to show that you do more than just work. In particular, sharing struggles with your work or stories of how you got to where you are can help others relate to you and dispel the myth of the scientific genius who is just born that way. Building a community organically takes time and concerted effort; we discuss how to do such a thing in another article in this series on best practices for using social media for science. Ongoing evaluation of your impact and user social media engagement will help you shape your strategy over time.

Implementing Your Plan: Access and Management

Now that you've thought through your goals, defined the community you want to connect with, decided on the appropriate platform(s), and brainstormed on the types of posts you're going to create, you need a way to manage your social media. Many platforms can be managed by multiple users, allowing a research lab to spread out the work over time and share responsibility, while reducing the burden for each individual to have exciting content as frequently as necessary to keep people engaged and provide value. Some tools that assist in content planning include post management systems and graphic design programs. Social media management systems, such as Hootsuite, Buffer, and Sprout Social, allow you or a team to schedule social media posts, track engagement, and log social media content. The downside of these social media management systems is that users must pay for them monthly, at least $15 per month. Scheduling posts maintains consistency and limits your need to switch from task to task just to post an update. This means that you can design specific posts ahead of time and then schedule them to be posted later, perhaps at a time when you know your users tend to interact with your posts. Beware of the limitations of such systems: scheduling posts provides peace of mind if you're traveling, in the field, or otherwise unavailable to post at an exact time, but you should also strive to be responsive on posts. If people comment on your scheduled post, respond in a timely manner.

A multitude of tools can help you create eye-catching graphics to professionalize your social media content, many of which are free for basic or introductory use or may be licensed through your organization. Graphic design tools including Canva and Visme can help you create branded posts, meaning that all content you create has a similar color scheme and font choices. These sites are especially helpful for creating images that align with the size constraints of individual social media platforms: images on a Twitter post are longer than they are wide, Instagram's images are a square, and Facebook's image constraints vary based on where you want to post your image, such as a regular post, an event, or a page banner. Additionally, Canva is a great tool for creating infographics, which are a great way of showing information in a creative and easy-to-digest manner. Photos and icons can help make images you create for social media stand out, and there are a lot of free photo and icon repositories, including unsplash (for high-resolution photos) and flaticon (for vector icons). UF/IFAS maintains a photo repository as well. To encourage diversity in STEM disciplines, try to feature people from diverse backgrounds whenever possible, because people are inspired to become what they see. One free content provider on Pexels.com, Christina Morillo, has a whole collection of women of color in tech at https://www.pexels.com/@divinetechygirl. For more on diversity and inclusion in social media, please see our article in this series, Diversity and Inclusion. Finally, always be sure to properly credit any image use, even if it is your own image.

Summary

Planning your social media and setting SMART goals for its reach can help to make your social media more effective and engaging, as well as easier to manage and ultimately measure its impact. Taking the time up front to establish who your community is and what platform(s) you will use, as well as developing messaging strategies, will allow you to share your research broadly both inside and beyond your academic circles.

References

Bex, R. T., Lundgren, L., & Crippen, K. J. (2019). Scientific Twitter: The flow of paleontological communication across a social network. PLoS ONE 14(7), e0219688

Cardoso, M., Warrick, E., Golbeck, J., & Preece, J. (2016). Motivational impact of Facebook posts on environmental communities. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing Companion (pp. 237–240). New York, NY: ACM.

Cothran, H., Wysocki, A., Farnsworth, D., & Clark, J. L. (2019). Developing SMART Goals for Your Organization. FE577. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe577

Daume, S., & Galaz, V. (2016). "Anyone know what species this is?"—Twitter conversations as embryonic Citizen Science communities. Plos One, 11(3), e0151387.

Lundgren, L., Crippen, K. J., & Bex, R. T., II. (2020). Social media interaction as informal science learning: A comparison of message design in two niches. Research in Science Education.

Rubin, R. S. (2002). Will the real SMART goals please stand up? The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist 39(4), 26–27.

Appendix: Documents in This Series

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: Basics

An overview of uses of social media for researchers, platforms, and engagement types

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: SMART Social Media: Planning for Success

How to create a plan to determine your social media strategy including goal-setting, resource mobilization, and platform choice

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: Evaluating Your Success

How to determine progress toward your goals using platform metrics and qualitative techniques

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: Creating a Community through Best Practices

How to find your voice and build a community on social media

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: Diversity and Inclusion

How to use social media to promote marginalized voices and encourage a wider range of voices in conversations around research

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: How to Share Complex Research

How to break down a research paper into a series of engaging and concise social media posts

Using Social Media to Engage Communities with Research: Social Network Analysis for Community Evaluation

How to determine who your social media community is by analyzing followers and connections